Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.30 n.1 Cape Town 2004

The making of an animal biography: Huberta's journey into South African natural history, 1928-1932

Leslie Witz

University of the Western Cape

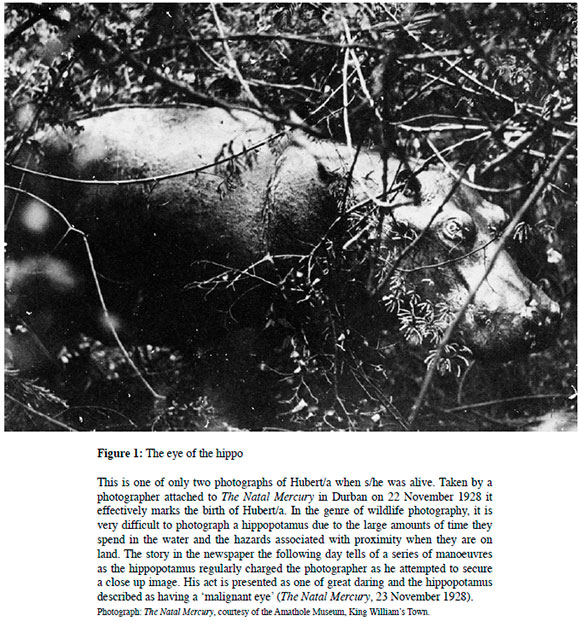

This article concerns itself with stories of a journey that have no temporal or spatial beginning and no apparent motivation. They are accounts of the travels of a hippopotamus in south-eastern Africa from 1928 to 1931. In effect the journey begins with an illustrated newspaper report. On the 23 rd November 1928, under the headline 'Adventures of a Hippo in Natal', The Natal Mercury reported the appearance of a hippopotamus in the sugar cane fields at New Guelderland, a village just north of Stanger, on the Kwazulu-Natal North Coast. A substantial portion of the report deals with how The Natal Mercury s photographer had risked his life by hiding in the thicket in order to obtain 'a unique close up view of the hippo.' This photograph, 'taken [from] two yards away', together with one showing 'a few of the excited Native and other spectators' accompanied the story. Thirty months later The Natal Mercury reported that the journey of this hippopotamus had come to an end. 'Hubert the Hippo', the headline proclaimed, had been 'assassinated'. His 'Great Trek' had ended '400 miles from his Tugela home'. Using language that insinuated that the killing was premeditated, the newspaper claimed that he had been 'shot through [the] head by [an] unknown sniper.' 'His bulky body' had been found the previous day, 23rd April 1931, 'floating in [the] Keiskama river', near King William's Town. In its Saturday edition The Natal Mercury published a series of photographs in memory of Hubert's travels: two taken at New Guelderland in 1928 of Hubert in the bush, that had 'brought fame to his photographer', another of two policemen looking at possible hippopotamus tracks on a golf course near Durban, and an arbitrary photograph of a hippopotamus in the water. These photographs, the newspaper claimed, were 'intimate studies of a great character'.1

Almost immediately after the hippopotamus's death Guy Chester Shortridge, the director of the Kaffrarian Museum in King William's Town, and Nicholas Arends, his assistant, claimed the body for their institution. After having skinned the animal, they sent it to London to be mounted, in preparation for display in their museum. Upon return to South Africa she (her gender was discovered at death) was displayed at the East London and Durban Museums and the Rand Easter Show before becoming a permanent exhibition at the Kaffrarian Museum in 1932. Huberta became the Kaffrarian Museum's major attraction. A little over seventy years later, the Amathole Museum, as it was renamed in 1999 because the former name was considered to be 'insulting and offensive' by members of the local community,2 still markets itself as the 'Home of Huberta', and the gift shop is called 'Huberta's Hoekie' (Huberta's Corner).

Alongside the process of museumising Huberta was the publication of a veritable plethora of books on his/her travels. Between 1931 and 2001, eight books were written specifically about Hubert/a. Another book on The World of Big Game, devoted almost half of its seventy-one pages to 'The Story of Huberta', and for one of the books on Huberta a study-guide for learners was published in 1993.3 These books, most of them written for young children or teenagers, were lavishly illustrated, and resorted to wilds leaps of the imagination to fill in gaps and construct a coherent and interesting narrative, with the hippo cast as the central character.

Finally, in the interests of promoting regional tourism, Huberta has, in recent years, metaphorically been returned home to Kwazulu-Natal. She has become the icon of tourism to Richards Bay. Lodges are named in her honour, and the local tourism association has formed a committee 'to research Huberta's historic journey, which started from the Mhlathuze lagoon in Richards Bay, and to come up with the appropriate ways of honouring "South Africa's favourite hippo."'4 Huberta has reversed her journey and, although she is still on display at the museum in King William's Town, in effect her home is in the wild life sanctuaries of Kwazulu-Natal, sustaining an image economy of eco-tourism.

My primary concern in this article is with the images of Huberta that were generated immediately after her death on the banks of the Keiskama. I am interested in the different ways that understandings of South African society and its history are rendered through the representations of this hippopotamus in a display in a museum and through textual biographies of its life. It might seem rather unusual to focus on stories and the displays of a hippopotamus to try and realize such insights. The motivation for this investigation lies in the power of natural history, particularly in museums, to appear as a 'model of neutral transmission'.5A substantial body of writing over the past two decades, about the collection, classification and display of humans in natural history museums, has exposed the fallacy of this supposed neutrality. Very broadly these writings have shown how natural history collections are 'historically, geographically and socially constituted'. Their very naturalness is 'culturally constructed and sustained', in the process reproducing and legitimizing certain ideas about society.6 More specifically, the collections and displays of indigenous peoples in natural history museums in South Africa, it has been argued, were based upon racialized notions of society that often had their origins in colonial encounters and the pursuit of research in the field of physical anthropology.7 Yet, in these writings, very little attention is paid to what is often the central feature of natural history museums, the collections and displays of animals and plants. Clifford's point that collections have a tendency to 'suppress their own historical, economic and political processes of production'8 is no more evident than in natural history museums where animal and plant displays are regarded as specimens, given 'common' and/or 'scientific' names, and situated in exhibits that claim to reproduce the natural surrounds and/or an associated field of research and/or environmental awareness. How the plants and animals were acquired and the cultural meanings that are associated with them finds little place both in natural history museums and/or writings about them.9

The exception here may of course be dinosaurs where the process of the find is sometimes elaborately presented in museum displays. Yet even in this case the exhibition nearly always reproduces the scientist as a discoverer of an historical reality, with little recognition of the 'cultural and social forces' that drive scientific work. Mitchell, argues, for instance, that the cultural and scientific status of dinosaurs are 'deeply entwined' with each other. From his study of these intersections, he maintains that the dinosaur needs to be understood as a 'powerful cultural symbol'. He attempts to show the mediation of dinosaurs through 'icons, images, symbols, narratives, visual representations and displays, and the words that accompany them.' Importantly, while he argues for a central social and cultural purpose of the dinosaur as a totem of modernity, he demonstrates that its modes of representation and symbolism underwent significant shifts from the late eighteenth century to 1990s. From being sturdy mammoth like frames that were displayed in international exhibitions, symbolizing the power of nation states, they have turned into electronically generated images whose home is the internationalized postmodern world of the shopping mall and theme park.10

Although the same elaborate claims cannot, by any stretch of the imagination, be made for Huberta, Mitchell's methodology - an undertaking that he refers to as constructing 'the history of an image as the evolution of a visual species'11 - provides a way to investigate the cultural history of the most extensively represented single named animal in South Africa.12 From his 'birth' at New Guelderland in 1928 to her display in a museum and appearance as a marketing tool to promote tourism, Hubert/a has, in different ways, been romanticized as a 'national pet'.13 S/he has been given a human name, accorded the status of a domestic animal and adopted as a member of a human household.14 From 1931 onwards it was the status of domesticity and his/her 'national' habitat that shifted in the narratives and visual representations of Hubert/a. The early years of her life after death though set in place many of the key features that she was to maintain for many years thereafter. As his body moved from the banks of the Keiskama, into the galleries of Kaffrarian Museum and onto the pages of adventure stories, he changed his gender and she became an icon for the setting up of national game and 'native' reserves in an era of advancing racial segregation in South Africa.

The 'people who both rescue and kill'15

When Hubert's body was discovered on the banks of the Keiskama on 23 April 1931 the story of his life had been rather sketchy and incoherent. There were a series of random sightings - many of which were highly exaggerated - and, apart from the photographs taken by The Natal Mercury S photographer at New Guelderland, there were no other photos of him alive. No one knew where the hippopotamus had come from, what its gender was and why s/he was wandering. But this did not mean that s/he had not been extensively biographised. From the days of his 'birth' at New Guelderland, newspapers, in South Africa and abroad, had followed his travels as he made his way down the coast of southeastern Africa. As he evaded capture and regularly disappeared from public purview, he was anthropomorphized as 'witty, amusing, bored, exciting, depressed and clever'.16 One might also add to this list 'playful' and 'shy'. Although he supposedly ate crops and attacked people, he was never characterised as a real 'menace' nor as very 'dangerous'. Key moments in the tales were his apparent appearance in Durban's main thoroughfare, West Street, on April Fool's Day, 1929, at Port St Johns' town square in January 1930, the unsuccessful attempts by the Bloemfontein zoo to thwart his 'wanderlust' while he was based near East London in early April 1931, and then the 'tragic end' of his 'pilgrimage'.17

Two days after the discovery of the hippo's body an anonymously authored column was published in The Cape Mercury, the local newspaper of King William's Town. It claimed that that Huberta was the spirit of the Xhosa king Hintsa. What invited this comparison was Hintsa's betrayal by the British one hundred years before:

As you know and have read, he [Hintsa], in the innocence of his heart, delivered himself into the hands of the Government and left his son, Kreli, with them while he in person guided the soldiers to the place where the cattle he had taken in war had been kept. On the road the horses began to race. Mlungu [white man] I ask you, who have the blood of riders in your veins, what happens in such a case. The Chief led while the rest followed, but the cry was raised that he was escaping. His horse was shot and he sought sanctuary in the forests of his ancestors. Armed only with an assegai, he stood alone at bay and was killed by the lightning of the white man's weapons, with no evil intention in his own mind.

Mlungu, consider the plight of those who put themselves under the protection of the Government and whose trust is to be found in the broken reed. We only seek justice. At whose hands will we find it when the writ of the King no longer runs. At those of Omasiza Mbulala? (the people who both kill and rescue).18

Speaking through a ventriloquised 'native' voice, to a largely white readership in the King William's Town area, the writer of the column had aligned the two killings, condemning the use of arbitrary violence, especially when they (the settler population) should be those offering and guaranteeing protection to those who require it (Hintsa and Huberta). This column, which squarely lays the blame on the British for the killing of Hintsa, appears in direct contrast to white settler historiography at the time, where the Xhosa king appears as a treacherous and devious character, who was killed by the British soldiers in an act of self-defense.19 Yet this was the period of debates over implementing systems of reserves and retribalization (the Native Authorities Act of 1927), and later trusteeship, under the auspices of the increased power of the Native Affairs Department, with its regional headquarters in King William's Town.20 Such a column can then be read as supporting forms of control, not through brute force, but through the protection of tribal reserves for 'natives' and game reserves for animals.

But, somewhat ironically, it was a different set of 'people who both kill and rescue' who created a visual biographical narrative of the wandering hippopotamus. These biographers, however, were not those who either had killed Huberta or, more generally, those supposedly who were in favour of displays of aggression and domination. Instead they were those who purportedly rescued her for posterity, the director and his assistant at the Kaffrarian Museum, Guy Shortridge and Nicholas Arends, and the authors of the first two full-length Huberta biographies, Hedley Chilvers and G.W.R. Le Mare. Through arranging for her body to be reconstructed and by compiling textual narratives, using the newspaper stories and the limited photo archive, the route of Huberta's life was literally mapped along the south-east African coast from Lake St.Lucia in Kwazulu-Natal (as her presumed place of birth) to her death on the Keiskama.

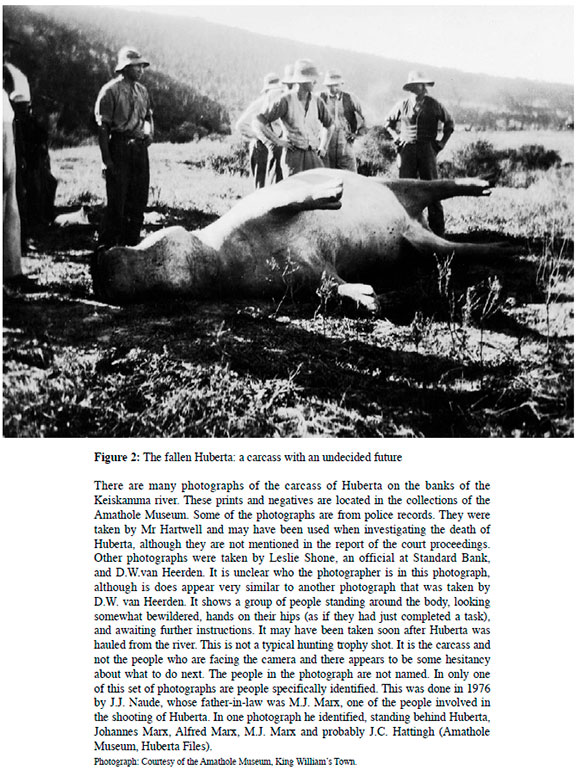

It was from the bodily remains that the visual image of Huberta in the museum was created. This was no easy task. The first problem was whom the body belonged to. Those who shot the hippopotamus apparently had no desire to claim the body, although there were some insinuations made later, when a group of farmers were put on trial, that they wanted the skin to make whips. The hides of hippo were greatly sought after specifically for this purpose by South African farmers, who had used them since the seventeenth century as sjamboks.21Together with a demand for hippo meat and trophies from hunting expeditions, this had led to hippopotami being exterminated in the Cape by the 1870s.22 But, in this instance, some sixty odd years later, there does not seem to have been a demand for the skin or the meat. The farmers had hauled the dead body from the river, where it had risen 'owing to the development of gases in its bowels' after probably spending eight to ten hours on the river bed.23

The Durban Museum and the National Museum in Bloemfontein staked their claims. The former asserted that Huberta came from the region and had made her public appearances in or near the city. Bloemfontein's claim was based upon their attempts to capture Huberta for the zoo when she was alive.24 But, it was King William's Town, which up until Hubert/a's death, had not played any role in the saga of her/his travels, which seized the body. A pamphlet produced by the Amathole Museum recounts how the museum 'took possession' of Huberta:

The day after hearing the news of the shooting at the Keiskama River, he (Shortridge) and his assistant, Nicholas Arends took a taxi to the scene. They persuaded a number of local farmers to help in the skinning of the rapidly deteriorating carcass, and finished the task by 11 pm on the 24th April. The next day the hide and skull were taken to King William's Town by bus. While Nicholas Arends laboured at cleaning the remains, curious onlookers trampled the museum's garden and surrounding fence. Sympathy cards and donations for Huberta's mounting poured in.25

Given the time and effort expended by the museum's staff, the mayor of King William's Town, J.W. Bryson, claimed that 'it was cool cheek on anyone's part to try to obtain possession of what was King William's Town's legitimate right.'26

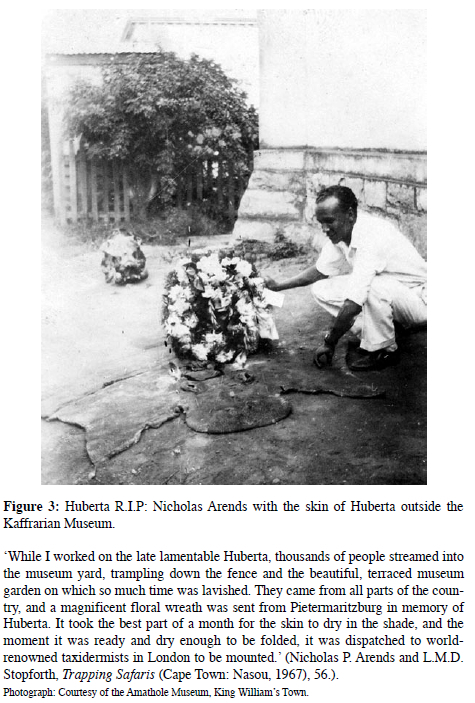

The second problem concerned the changing shape and form of the body after death. A modern manual on methods of collecting and displaying animals suggests that, in order to try and record and preserve the features of the body that the 'animal be skinned as soon as possible.'27 This was not possible in the case of Huberta. Shortridge wrote that he had a 'difficult and unpleasant time fixing up the remains as the animal had been dead for about three days and had been lying in the sun.'28 Arends relates in his published memoirs how he removed the flesh, shaved and curried the hide, and boiled, bleached and cleaned the skull. Given the size of the hippopotamus he would have probably removed the skin in sections, removed the blood and faeces, and then carefully applied salt to it, ensuring that it covered 'all folds and creases in the skin'. The 'late lamentable Huberta' was ready to be mounted by the taxidermists.29

Taxidermy had flourished in the latter part of the nineteenth century as imperial hunters of big game sought to re-create lifelike images of the animals they had killed.30 The names of prominent hunters - Lord Kitchener, Frederick Courteney Selous, Oswald Pirow, DF Malan, JBM Hertzog, Sir Harry Johnstone - who made use of their services, were, in turn, used to market the capabilities of their taxidermy operations. These trophies were emblems of force, showing domination over animals and control of imperial possessions through conquest. The quantity of trophies - Selous had over 500, which included 19 lions and 10 rhinoceroses - their quality, by being well preserved, and the pose embodied in the trophies were all symbols of the hunter's ability and claims to heroic status. The taxidermist was required to show the animal in a way that indicated it was 'dangerous and powerful'. By implication it was the danger of nature on the frontiers of empire that the hunter had confronted and overcome.31

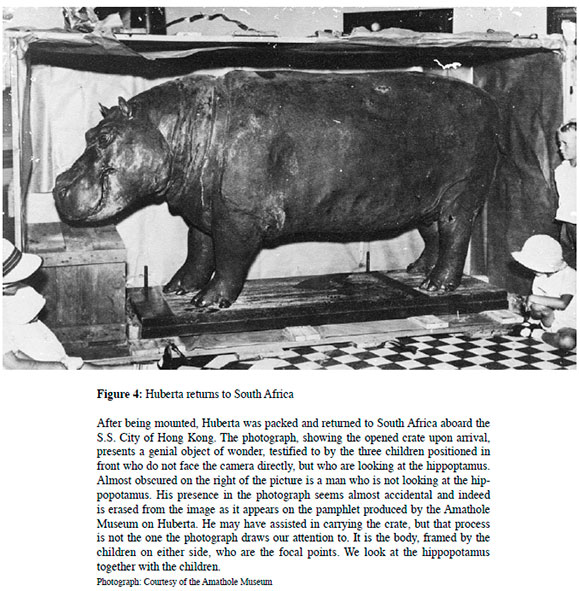

In the case of Huberta, there was an offer from the taxidermist at the Transvaal Museum 'for the scientific treatment and mounting of the Hippopotamus (Hubert)'32 at a cheap rate of £85. The Kaffrarian Museum, however, opted to send the skin and skull of Huberta to Edward Gerrard and Sons in London, a company they had used extensively in the preceding years.33 Gerrard and Sons had won medals for their work at the Paris Exhibition in 1900 and the St. Louis Exhibition in 1904, had amongst their major clients Lord Baden-Powell, Lord Rothschild and the Maharajah of Gwalior, and had mounted specimens for museums in Britain, the USA 'and all the colonies'. They assured clients that collections would be 'carefully packed, stored or moved'. Shortridge was, however, critical of some of their work that he had recently seen and wanted them to take care with Huberta. In response to Shortridge's criticisms they cited the vagaries of clients who made their work difficult. Sometimes the clients wanted quality but were not prepared to pay for it. At other times they wanted their mounted animals to have a 'well rounded and full body', after they had used the skins for a year as a rug.34

In creating visual representations of animals for museums, the work of the taxidermist is presented as trying to reproduce, as faithfully as possible, the dead body as an image of the scientific 'facts' of animal life 'for habitat display'.35By making the animal body appear as live, taxidermists work in much the same paradigm as positivist historians, pretending 'to reinvigorate the dead skin of the past so that it [can] represent, even make a monument of, ephemeral reality.'36So, when Huberta's skin and skull went to London one reporter maintained that she had gone to tell her story, in the form of a 'personal interview', to the taxidermists, so that she could be reconstructed as a visual life history contained in the body.37

There were two key processes in reconstructing Huberta's history as a body: removing traces of death and then making the body appear as the life of the animal. The taxidermist had to ensure that the bullet holes were not in any way visible. By skilfully hiding the wound Huberta appeared as 'unblemished', as if she had not received any head injuries.38 Secondly, poses, expressions, movements and shapes of an imagined live animal had to be moulded using the animal's skin. Recorded measurements at time of death, photographs and existing knowledge of the body acted as the guiding tools. What taxidermists at the time generally did was to fit the skin on a frame constructed to broadly resemble the animal. Wooden wool was sewn into the frame to create a muscular structure. The skin would then be tried onto the body to make sure of the fit. Here it was important to ensure the skin had dried out completely. If it shrunk further cracks would appear along the seams at a later stage. Before the skin was finally attached a coat of pliable clay would be affixed to the frame. When the skin was attached, the clay could be moulded to effectively modify the appearance.39

In the case of Huberta, apart from the skin and skull, there was little to work on. Although she had been written about regularly, there were only two indistinct photographs when she was alive. In fact the most extensive series of photographs of Huberta are as a corpse on the banks of the Keiskama. These were certainly not suitable for modeling a specimen for exhibition. So, in the workrooms of Edward Gerrard and Sons in London, at a cost of £159, a hippopotamus was sculpted to give the illusion of the real Huberta that had been anthropomorphized in the press over the past three years. Returned to South Africa in January 1932, with all signs of her death carefully removed, Huberta had a suitably 'life like appearance' as the 'famous animal hiker', whose 'unconquerable spirit ... glows through the stuffing of the taxidermist.'40

The sculpted body (one book indeed refers to it as a life-sized statue)41was displayed to thousands of visitors in Durban, East London and Johannesburg before being 'suitably enshrined at the entrance of the ... Natural History building' of the Kaffrarian Museum.42 Her pose, in profile in a transparent glass case, was not one that accorded with an image of an animal that had been killed in a hunt. There were no signs of danger visible here. Huberta was a genial creature, with a closed mouth and no visible appearance of movement. She appeared as symmetrical, with her front and back legs firmly on the ground, parallel to each other. For an animal that had become known for its travels and wanderings, this was an image that lacked mobility. Taxidermy did not have what Asma has called the 'time-management technologies' of photographs and moving pictures. Thus the animal on display was not only 'cubicle bound', but 'also alienated from the distinguishing property of life itself ... motion.'43 But Huberta was unlike other animal exhibitions in natural history museums at the time. While '"hippo-de-move-on" was no more,'44 she was not merely a specimen in a glass case representing a taxonomic classification. Her stories had already provided a substantial basis for visitors to fantasize about her life and presume her thoughts.45 The wonder came from being able to see the animal that had been so extensively written and talked about, and that so few had actually seen when alive. The body made the stories of Huberta believable. It mattered very little that not much of a context of her life or environment was explicitly provided through the exhibition. The crowds flocked to visit her.

Yet there was the context of the Kaffrarian Museum and its extensive collection and displays of mammals as specimens. With the development of the category of natural history in the nineteenth century, the classification of animals had 'meant collection, and collection meant killing.'46 Landau points out that, at the beginning of the twentieth century, imperial hunts for game on a grand scale had been drastically reduced as animal populations were decimated. Although the activity of hunting remained firmly in place, it was increasingly framed in a discourse of serving the interests of museums, classification and science. This was no more apparent than in an exhibition in 1932 in the British Museum of Natural History entitled 'Game Animals of Empire'. Classified according to the colonies and dominions where they were collected, the animals on exhibition were presented as being 'threatened with extermination' because of agriculture and 'commercial exploitation' rather than hunting. Given the donation of the F.C. Selous Collection to the British Museum by his widow, in 1919, it is highly likely that a substantial part of this exhibition did derive from the voracious big game hunts.47

The Kaffrarian Museum's first full-time curator, Frank Pym, had initially built up its mammal collection. He had undertaken hunting expeditions both locally, on farms in the area, as well as more widely, in East Africa. According to the official history of the museum, one of its 'proudest possessions' is a large buffalo, shot in 1906, on a hunt organized by Pym on the farm 'Elephant Park', near Bathurst in the eastern Cape. Given the name Wolsak, the buffalo still stands today, adjacent to Huberta, in the Natural History Building of the museum. Cordoned off by a set of ropes, visitors are requested, by a notice, not to touch Wolsak. At Wolsak's feet there is a photograph entitled 'Wolsak and the Hunting Party'. The photo shows a group of hunters (six men) gathered around the body of Wolsak. One is informed in the caption that the photo was taken by Frank Pym. Identified on the back row are Mr. Job Timm, with his sons Fred, Maynard and Stuart. On the right are Mr. William Pike (Standing) and Mr. Rio Timm. The two figures at the front of the photograph are holding their rifles at an angle almost forming a monumental arch over the animal's body, while resting on Wolsak's horns is another rifle. The others hold guns vertically at their side. The photograph, at Wolsak's feet, is displayed as a sense of fulfillment and achievement, of managing the kill and obtaining a 'fine', 'massive', 'specimen' of a buffalo for the museum.48

Shortridge and Arends, who had rescued Huberta by 'salvaging the hide'49- which formed the basis of the sculpture in the Kaffrarian museum - continued the practice of collecting mammals that Pym had begun, but on a much more elaborate scale. Almost on an annual basis from the early 1920s, they went on expeditions to collect/hunt for mammals. The British and American Museums of Natural History, who were, at the time, merchants of exotica, funded many of these collecting/hunting trips to Namibia, Malawi and Zambia. Shortridge provided these museums with specimens of 'animals of Empire' to display to visitors as imaginary inhabitants of 'faraway Africa'.50 It is Shortridge's 'great reputation amongst mammologists as a collector' that dominates in the short biographical sketches of him. Largely in the form of obituaries, these biographies relate his birth in Honiton, Devonshire in 1880, his arrival in South Africa during the South African War of 1899-1902 and then move quickly onto his collecting activities. They tell how, at the beginning of the twentieth century, he had collected bird and mammal specimens for the South African Museum in Pondoland, for the British Museum in Australia, New Guinea, Java, Borneo and Northern Rhodesia, for the Bombay Natural History Society in Burma and South India, and live animals for the London Zoo in Guatemala.51 Many more collecting expeditions followed his appointment as Director of the Kaffrarian Museum in 1922. During his tenure as director Shortridge went on thirteen collecting expeditions, collecting some 25,000 to 30,000 species.52 Many of these expeditions were to present day Namibia, where the colonial administration gave free game and shooting permits, information about the distribution of animals and made nearly all the transport arrangements. Their assistance was so invaluable that Shortridge recommended to the British Museum of Natural History that new species be named after several of these individuals. These expeditions were the highlight of Shortridge's life and in his correspondence with the British Museum of Natural History he expressed the feeling of 'gloom' when an expedition came to an end. 'I came back from my trips feeling about 25 years old.'53

Almost totally written out of Shortridge's biographies are any sense of a life beyond collecting birds and mammals. The major reason for this is that in spite of an enthusiasm for collecting, Shortridge deliberately appears not to have wanted to archive his own life. In 1977, when the museum's historian, Brian Randles, began researching Shortridge's life he discovered very little. A letter to Randles from Enid Shortridge, Guy's younger sister, explains this lack of information:

He . took all the letters mother had kept over some 20 years, - at one time he probably meant to write some memoirs, but he wasn't all that keen on personal stuff and probably tore them up. He loathed any sort of family 'reminiscences' and would fly into a temper if mother ever told family stories!54

According to Enid, her brother also did not like to be photographed and he 'used to tear up any [photograph] he found lying about.' More particularly she asserts that Guy did not want himself portrayed in the image of the big game hunter.

He was certainly not the comic paper prototype of the so-called 'sportsman' who shot some fine animal and then got himself photographed with one foot on its head and a wide smirk under a solar topeé! (Thank goodness.)55

This story of a reluctance for the trophy hunt is placed alongside an anecdote of Guy, aged three, bursting into tears when he saw a picture of Christian martyrs being fed to the lions in Rome. Apparently Guy's concern though was not for the martyrs, but for the lions. 'That poor lion hasn't got a Christian,' he 'bellowed indignantly.'56 Field Marshall Allenby, under whom Guy Shortridge served in Palestine during the First World War, was also concerned to place Shortridge's monumental two volume work, that identified the features and location of mammals in Namibia, as being of use to the 'real sportsman' who was a 'student of Nature'. Allenby commends such 'students' for deriving more pleasure from studying animals that are alive and shooting with the 'camera instead of the rifle.'57 Shortridge's biography, almost totally stripped of any personal information, thus reads like the story of a Christian saviour whose life task was to rescue animals for science and nature.

The irony was that the work of collection in the natural history museums in the first half of the twentieth century was primarily through hunting animals by trapping and shooting, and then sending the specimens on to taxidermists (who worked for some of the world's major game hunters) for mounting. This is no more apparent than in another set of biographies of Shortridge, written by his assistant, Nicholas Arends. These are contained in an obituary that appeared in The Mercury of King William's Town on 1 February 1949, a book on the activities of trapping animals for museums, published in 1967, and Arends' unpublished autobiography, 'Retrospect', written in 1973. In all these instances the biography of Shortridge is refracted through the autobiography of Arends and the latter's work for the museum. Unlike Shortridge, Arends was very concerned to archive and narrate his life, making claims to be 'one of the most versatile personalities: Naturalist, taxidermist, collector, educationist, philanthropist, war worker, cultural and economic personality and politician.'58 Arends' autobiographical renditions are filled with proclamations of his 'achievements' in the separatist realm of 'coloured politics' - he writes in 'Retrospect' that one of the most serious matters that concerned him 'was that Coloured children were registered at the Magistrate's offices registry office as Native -'59 and of his work for Shortridge.

He had arrived in King William's Town in 1922 and found employment as Shortridge's gardener and cook. As he started accompanying Shortridge on his collecting expeditions, he was inducted into the world of the museum, becoming a highly skilled trapper and skinner of animals. He tells of the preparations for expeditions - gathering together the essential collecting tools: mealies for trapping small animals, arms and ammunition to hunt larger ones, and knives for skinning. The technical aspects of collecting and the close friendship, he maintains, developed between himself and Shortridge, with the latter becoming a father figure in his life. 'In between trips', writes Arends, 'I lived at his home. We had breakfast together, had lengthy discussions by the light of the flickering camp fire, and took long walks in the veld during the day-time. His wisdom, experience, and sympathetic understanding gave direction to my life and work.' The discussions which they had, according to Arends, were sometimes very serious, 'about future expeditions, the various facets of mammal collecting, birds, botanical specimens, mineral deposits, stone implements, ethnographical specimens, reptiles, marine biology.' Then there were lighter moments, 'when we could laugh together like two school boys.'60 The 1949 obituary of Shortridge, written by Arends, highlights the 'safaris' they went on together and the joy and pride in the capture of animals:

The happiest moments in his life were at early morning, before morning coffee, when I spread out the night's bag of catches and when we returned from the early morning (dawn) hunt - which was always the most fruitful - it was quite a common thing to spread out 25 to 30 specimens daily to be measured, skinned, preserved, stuffed and carefully pinned out.61

Several 'notable captures' that Shortridge made are pointed to in the obituary: 'when he got a black rhino in South-West Africa, the magnificent giraffe in the Kaokoveld, the hippo in the swamps of the Okavango ... ; ...we trapped a lioness in the jungles of the Okavango; ... we bagged the recent black rhino and her calf in Nyasaland.' Included on this list of 'notables captures' (and which does not appear either in the Shortridge obituaries in the South African Museums Association Bulletin and in Nature or in the entry in the Dictionary of South African Biography) was when 'we skinned Huberta on the banks of the Keiskama River.'62

Huberta was not the first hippopotamus to take its place amongst the collections of the Kaffrarian museum. Capturing hippopotami was one of the major objectives set by Shortridge for the 1929 expedition to the Okavango and Western Caprivi. First a hippopotamus was shot for the British Museum and then another for the Kaffrarian Museum. Nicholas Arends describes the killing of the second hippopotamus at length in his book Trapping Safaris:

. before I even had time to take aim, the hideous and rather fearsome creature emerged from the reeds no more than five yards away from me . As I was standing in a ten-foot deep donga, formed by the passage of countless hippos through many centuries perhaps, there was nowhere to escape to except forward - in the direction from which the hippo was charging. I raised my rifle blindly and fired, praying as I did so. The bullet went home and the hippo dropped dead no more than three feet away from me, rolling over on its side in the mud and slush.

Arends then goes on to describe how he 'began to take measurements, standing waist-deep in the slush; the length of the body, the circumference of the neck, the shoulders and the abdomen, the height at the shoulder.' He then began to skin the hippo. 'I felt like a doctor performing an abdominal operation on a kitchen table with a patient lying on his stomach.' The skin was then taken back to camp. In addition they 'took some meat and eight gallons of pure white dripping.' In the evening they feasted on the hippo meat. 'I had my first taste of hippo's saddle and steak, and very appetizing it was too.'63 Eating of hippo flesh had been a common occurrence in game hunts at the beginning of the twentieth century. A book on the Game Animals of Africa, published in 1908, cites the game hunter, F.C. Selous commenting that the meat of young hippo was 'exceedingly good, better in my opinion than any antelope.' A Natural History of South Africa, published in 1920, also asserted 'the flesh of the Hippo is excellent, as all writers who have partaken of it testify.' And Shortridge himself commented, in his two volume Mammals of South-West Africa, that hippo meat, 'particularly that of half-grown animals, is excellent, and resembles prime veal both in flavour and colour.'64

The contrast between Arends' story of killing the hippo in the Okavango and the stories of Huberta is marked. In the story of the Okavango expedition the hippopotamus appears as a dangerous animal. Although given the same skinning as Huberta, this (unnamed) hippopotamus is not regarded as a creature to be mourned. But Huberta would not have been possible, especially in the Kaffrarian Museum, without the technologies, knowledge and relationships with an internationalized world of hunting and collecting. From their experience on mammal hunting/collecting expeditions over the previous decade, the museum staff was skilled in skinning and cleaning the animal body, transporting it to the museum and then dispatching it to the taxidermists in London who worked for big game hunters, museums and international exhibitions. At the very basis of their claim for Huberta's body were the assertions that the Kaffrarian Museum was a major centre of mammal collecting in South Africa, that Guy Chester Shortridge, was someone who had 'expert knowledge' in this field, and that he had used this knowledge by taking the swift action that had ensured that the skin of Huberta was saved.65 Such work of meticulously acquiring, skinning and storing the animal body was, according to Arends, that of the 'true naturalist'. Arends found 'immense satisfaction in seeing specimens trapped by him on display' and he recalled that Shortridge had always told him that 'we were collecting for posterity.'66

It would also have been very difficult for Huberta to go on display at the Kaffrarian Museum if the activities of the museum hunters had in any way been aligned with the killers of Huberta. The latter were being characterized in the press as 'vandals', 'savage men' with a 'lust to kill', 'cowardly' and 'low miscreants'.67 Almost inevitably, one of the first reactions was that black people had carried out the killing. A letter writer suggested that there be a reward offered and that knowledge about this 'be circulated among the natives.' In addition, the suggestion was made that a 'native detective' be assigned to the case so that the means of transport of the killers and the place where they camped could be ascertained.68 But this angle of investigation did not last long. The precision weapons used and the location of the killing, on land owned by white farmers, counted against such a theory. It also did not fit into the ventriloquised voices of 'native' narratives, referred to earlier and that were to become such a key component of Huberta biographies. In these purported 'native' narratives, Huberta was the 'reincarnated spirit of one of their departed chiefs,' whom 'the White man ha[d] slain'.69

On 21 May 1931 a group of four farmers walked into the King William's magistrate's office and confessed that they had shot and killed a hippopotamus on the farm De Hoop, in the Peddie district.70 The trial of the farmers, on charges of illegally hunting a hippopotamus that had been declared royal game, took place before a packed court room in King William's Town, on 27 May 1931. It was a spectacle, with the Kaffrarian Museum ensuring that Huberta watched over the proceedings. A court reporter for East London's Daily Dispatch described how a small display was exhibited on the table of the public prosecutor. On one side was Huberta's skull, which Shortridge and Arends had rescued from the farm. It lay 'plain and inert . stripped of flesh, showing gaping holes above the eyes and at the side of the jaw, where bullets had crashed in.' Alongside the skull were the weapons that the accused had used: 'four rifles that were packed against the . table.' When Shortridge gave evidence, he identified the skull as the same one belonging to the body of the hippopotamus he had seen at the farm De Hoop on 23 April 1931 and pointed to two of the accused as being present at the time. The accused, speaking in Afrikaans, did not deny that they had shot the hippopotamus, but said that they had done so out of ignorance. The owner of the farm, Nicholas Marx, said that 'he had never been to school and could neither read nor write, not even Afrikaans.' He maintained that they were intent on shooting 'an unknown animal on their land' and cast himself in the same vein of the museum hunter/collectors: 'My intention was to shoot the [unknown] animal and give the skin to the museum. I did not know I was doing harm.'

This comparison, that called attention to the practices of the museum, had to be countered by one that set up an alternative motive. The prosecution called 'Jacob, an elderly native servant on Nicholas Marx's farm', who said that Marx had told him that they had shot an animal 'from whose hide sjamboks are made.' In this way the killing appeared to be for material gain and not in any way associated with the collecting interests of the museum. Although Marx claimed he had only made these remarks after he had seen the body, the magistrate found the stories of Nicholas Marx, his two sons, Petrus Johannes and Nicholas jnr, and his son-in-law, Johannes Christoffel Hattingh, unbelievable. 'The evidence leads me to believe that that you knew the animal in the river was the wandering animal so much discussed,' the magistrate said, with a court interpreter translating his judgment into Afrikaans. 'My opinion is that the act was one of wanton destruction.' Each of the accused was fined £25 or three months imprisonment. Those who shot Huberta became characterized as simultaneously ignorant and deliberately 'wanton' killers of a 'harmless' animal.71 The museum's hunting/collecting activities, on the other hand, were dissociated from those of the killers. Instead, the Kaffrarian Museum and its Director, appeared on the side of justice, thereby further legitimising their rights to appropriating Huberta's body for collection and display.

Saving nature and 'natives'

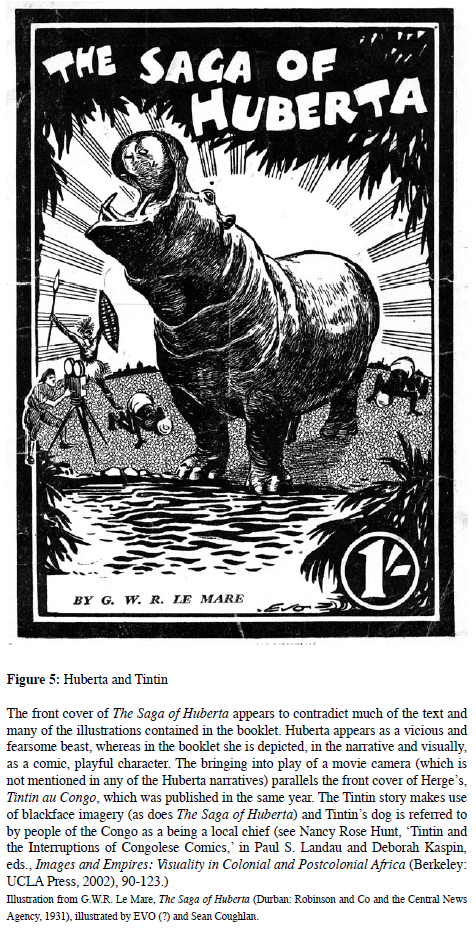

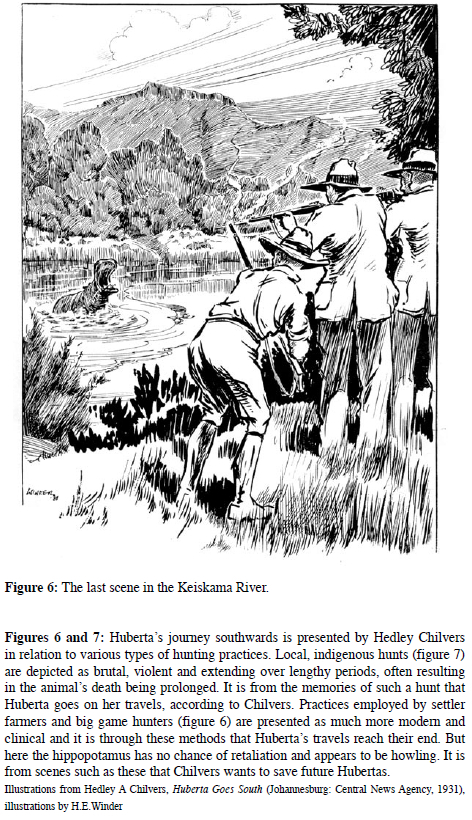

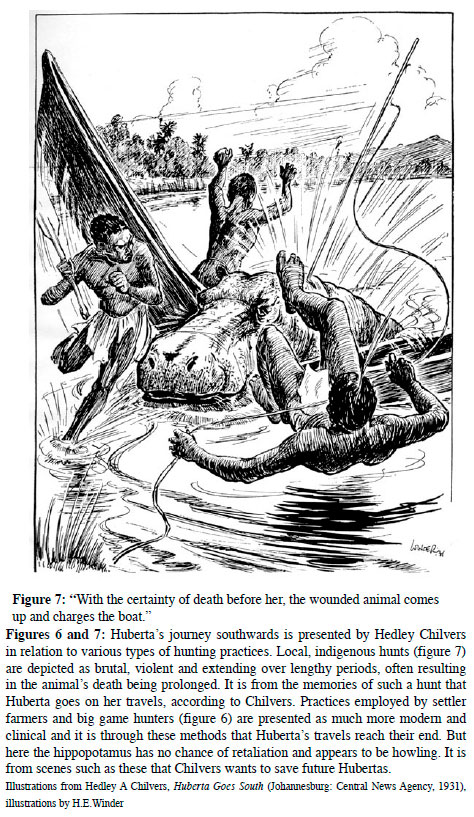

As Huberta was on her way to London, the first books on her travels were already in the process of production. By June 1931, The Natal Mercury, had published a 26 page booklet, written by G.W.R. Le Mare, which largely contained extracts from newspaper reports and the very few press photographs of Huberta. In this booklet, Huberta is presented as a comic-type of character and accompanying the photographs and the text are playful cartoon figures of a hippopotamus. At the end of the year the second Huberta book appeared on the shelves. Huberta Goes South, written by the Rand Daily Mail journalist, Hedley Chilvers, fills out the story considerably by drawing upon selected anecdotes from South African history. Instead of using photographs, the text is accompanied by a series of line illustrations of imaginary scenes in Huberta's life and death, drawn by H.E. Winder. This book also contains a section by C.Selwyn Stokes, which presents some of southern Africa's national parks, details a few of the animals that fall within their boundaries, gives a brief account of some of their habits and outlines some of the facilities that are offered to tourists.72

It is instructive to return to the initial report of the 'birth' of the hippopotamus in The Natal Mercury in November 1928 to begin a consideration of how she came to be imagined in these books. The story of the 'unexpected visitor to the Stanger District' appeared together, in the same columns and under the same headlines, as the 'Nagana problem in Zululand' and the policies of the government on 'game preservation'. The piece on nagana dealt with how this disease, transmitted by tsetse fly, was affecting the 'settler stock'. Farmers were claiming that wild game, that were being protected in the game parks which had been established in the area over the last thirty years, were the hosts of tsetse fly, which carried trypanosomiasis. In the area of the Umfolosi game reserves, 'regarded as magnificent cattle country', large numbers of cattle were being ravaged by naga-na. Farmers were lobbying local and central government authorities for game reserves to be deproclaimed and to allow for the destruction of game animals.73As in central Africa the farmers came up against strong resistance to these ideas. White points out that game reserves had initially been created at the end of the nineteenth century with the dual desire of maintaining contact with nature as a therapeutic measure for the modern world and as means to exercise power over nature. The latter was most apparent at the time, with reserves being established to replenish wild animal stock for colonial hunters by expelling and keeping out African hunters, who were cast as poachers.74 But by the 1930s a dramatic shift had taken place, in which the former desire was much more manifest. The game reserve was increasingly regarded as a 'therapeutic wilderness . an antidote to the ills of modernization, a compensatory space where senses dulled by the experience of industrialization could be restored.'75 Wild animals were no longer objects of the hunt but creatures to be romanticized. The response to the farming lobby, by the Minister of Lands, Piet Grobelaar, as reported in The Natal Mercury alongside the story of the traveling hippopotamus, expressed concern about the way that species were being exterminated. He was worried that if reserves were to be deproclaimed, as demanded by the farmers in Natal, the white rhino would be threatened. Instead he proposed a policy in which all game reserves would be placed under a national authority, with a board of trustees to control them. This would ensure that the country's animals 'could be better interpreted, understood and appreciated by the camera than by the rifle.'76

In the midst of this debate over game reserves that the stories about the wandering hippopotamus began to appear, culminating in the publication of the two books on Huberta. Chilvers dedicated his book 'To all true lovers of nature' and Le Mare's booklet was 'published in the interests of Wild Life Protection.' Huberta Goes South was explicitly linked, and placed alongside, a narrative of the emergence of national parks. At the same time as the natural history museum, with its hunting/collecting expeditions, was presented as saving animals for scientific study, the national park with roads, comfortable bungalows, grocery stores, and petrol depots (all offered along with 'native service' which was 'provided free to hirers of guest houses') was presented, by Selwyn-Stokes, as a 'living museum to wild-life and nature.' Tourists, with their cameras, were presented as embodying the characteristics of 'ardent game-protectionists'.77

The antitheses to the game protecting tourists are the different hunters who frame the story of Huberta's journey, as told by Chilvers. The frontispiece illustration is of 'The last scene in the Keiskama River', where three men wearing broad rimmed hats, and safari-type suits, are shooting at a howling hippopotamus. The next illustration, opposite page 22, is of the boat of three African hunters, wearing only loin cloths, being toppled by a hippopotamus that they had wounded. The African hunters provide, for Chilvers, the possible motive for Huberta's movements. He describes a 'native attack on a herd' of hippopotamuses on the Zambezi as premeditated savagery, ending with a 'feast on the ... carcase'. According to Chilvers, it was the deeply embedded memory of a similar 'massacre' that fuelled Huberta's desire to withdraw from the herd.78 Chilvers' account ends with the killing on the Keiskama and the appearance of the farmers in court. Significantly, he does not accord blame on the farmers for killing Huberta, pointing out that they had acted out of ignorance and were no worse than big-game hunters, whom were 'still tolerated if not admired.' 'Why esteem one act and condemn the other?'79 he asks rhetorically.

The big-game hunter and his stupid pretensions are not needed, unless perhaps on rare occasions when called upon to deal with raiding lions and leopards. And while of course the farmer must be permitted to shoot buck or baboons which destroy fences and crops, and while also the wayfarer remote from civilization should be allowed to shoot 'for the pot,' yet there must be the sternest reprobation of cowardly gunmen in fast well-provisioned cars who pursue and fire into herds on the veld. They are no better than that vandal, who, in the name of sport, once turned a machine-gun on to a herd of giraffe.80

Through his story of the killing of Huberta, Chilvers presents himself as a moral campaigner, seeking to save South African wildlife and nature. This is done by turning Huberta's death into an emblem of the need for National Parks that could not be easily deproclaimed and would serve tourists. These parks would not only keep out the African hunter labeled as 'poacher', but also the 'licensed gunmen who write bad books about themselves adorned with portraits of authors sitting importantly on the heads of their victims.'81

But Huberta is not only representative of nature. She also embodies the images conjured up by a ventriloquised 'superstitious' 'native' voice. In The Saga of Huberta and Huberta Goes South, she assumes the spirit of Shaka and becomes, alternatively, a reincarnated 'rainmaker", a 'witchdoctress' and a 'ghost from the Beyond'.82 This is expressed most elaborately in the book by Chilvers: '"Yebo!" they cried, "Behold the spirit of Tshaka seeking his lost impis. Black he looks under the moon and his nostrils snort like thunder. Now are the great days of old come again!"'83 The authors attribute Huberta not being harmed to local inhabitants recognizing these spirits within her. One incident that Chilvers imagines for the reader is when Huberta is stoned by 'natives', who he says like 'all primitive people' have a 'partiality for stoning'. They stop the stoning when 'confronted by an old witch doctor.' 84

'Cease, fools!' he cried holding up both hands. 'Cease lest a spell be cast upon ye!'

Here indeed was the Old at war with the New! The Old, the withered embodiment of tribal superstition, with clawing fingers, bag of snake charms, bones and sharks' teeth; the New, the native product of the city, hybrid in outlook and with little respect for the white or black man's law. Certain of them laughed.

Raising his hand still higher the old man yelled: 'Death to all who stone him!'

The stoning ceased. The hushed assembly dispersed. The wizard walked away shaking his head. Huberta was left alone. Twenty minutes later three of the natives prominently concerned in the stoning were dead, killed by a fall of rock!85

The body of Huberta is turned into the spirit of 'nativeness', and those who supposedly articulate this belief are depicted as the bearers of both tradition and primitivism. The tradition is commended for asserting control over the 'detribalized' youth, and the primitivism is condemned for its backward-looking practices.

There appears to be a contradiction here between evoking traditions as a means of control and an essentialising perspective of Africans as backward, savage and superstitious. One way of exploring this incongruity is to look at some of the other books that were written by Hedley Chilvers. He was a prolific writer, especially at the time he was authoring Huberta's biography. In 1929 he published The Seven Wonders of Southern Africa, a history of southern Africa as a tourist guide. Out of the Crucible, published in the same year, is an account of the discovery and mining of the Witwatersrand goldfields. The following year he published an adventure book about treasure hunters in Africa, entitled The Seven Lost Trails of Africa. Two years after writing about Huberta, he was warning South Africa of an imminent take over by Japan, in The Yellow Man Looks On.86

There are several features of these books that are relevant for examining the way Chilvers images Huberta as a 'native spirit'. Underlying all the books is the notion of settlers from Europe as the bearers of civilization and progress to Africa, southern Africa in particular. They are the discoverers, conquerors, inventors, initiators and leaders. His concern though is that 'race hatred'87 has caused division within the settler communities. The races he refers to are not black and white, but settlers who claim a British or Dutch heritage. He warns that unless there is 'racial' unity under the British flag, there is a possibility that overpopulated Japan, casting its envious eyes on the resources and land, conceivably could conquer South Africa. 'From the overcrowded islands of the East,' he writes, 'from the land of the rising sun, formidable, eager and sinister, the Yellow Man looks on.'88 In contrast to settlers from Europe, 'native' South Africans are presented by Chilvers as forces of primitivism, and impediments to progress. He refers to the 'murderous exploits of the blacks', the massing 'black hordes', the 'wild tribes which swept down upon Southern Africa', and 'tribal dancing' which he maintains goes 'right back, into the Wild'. These then are the 'elemental' forces of nature.89 Finally Chilvers presents various options to deal with what he calls the 'native problem': 'that there are four natives to every white man in South Africa.' These are framed in two ways by Chilvers. The first is to develop a road out of 'barbarism' under European tutelage, such as that provided though mission education. Secondly, he looks at the various systems of 'native' governance that are being practiced, from more direct forms of control, through to indirect rule, where elements of 'tribal' and 'chiefly' authority are invoked. The latter path is the one he seems to favour, as long as it is 'consistent with humanity'.90

What Chilvers' writings alert us to is an ongoing debate about 'native administration' that was particularly vigorous in the late 1920s. The Native Administration Act of 1927, based upon a policy of retribalisation and the use of customary law, gave chiefs jurisdiction over matters that were specified, by whites, as 'native law and custom'. This system would be controlled by the Native Affairs Department, whose power over Africans was strengthened considerably. It would 'repress dissent, promote cultural ethnicity, and distance Africans even further from the law as applied to white South Africans.' But this form of control through customary law was not unanimously accepted within the ranks of the Native Administration Department. Giving legal authority to chiefs and tribal authorities was inconsistent with the sometimes virtual disappearance of these powers in many areas. Retribalisation would therefore be imposing a system that had no existing basis. Moreover, although members of the Department welcomed the greater control that was given to them, they also wanted to ensure that the veneer of providing protection to 'natives' was maintained, so that it was not seen as what it was becoming, 'a manifestly coercive institution'.91

As Huberta's wanderings were positioned in a debate about the future of game parks in relation to farming and hunting practices, so her body was inscribed with contests over the most appropriate method to control the 'native'. Chilvers' view was quite clear. What he called the 'spirit' of 'war' could be maintained as long as it was safely stored away in areas specifically set aside for Africans and that they be kept in these places for eternity 'held in strict leash there by the law.'92 The African voice, invoking tradition through Huberta, was an assertion of white control through the politics of retribalisation. National parks were being set aside for animals and tourists by expelling colonial and African hunters. The former could continue their activities through hunts for museums that were cast as scientific expeditions or become tourists armed with cameras. The African hunters were being forced into the 'native territories', as their supposed 'natural home', where, on newly established tourist routes they could be 'conveniently seen' 'combined with scenic attraction[s]'.93

Not only does the wandering hippopotamus embody a spirit of 'native-ness' in these books, but also, very explicitly, she is gendered as female. Le Mare, very early on in his text, explains that he decided to use the female designation, Huberta, rather than the male one, Hubert. He based this on a communication from the curator at the Kaffrarian Museum confirming the gender of the dead hippopotamus as female.94 The explanation offered is one that asserts the gender as a reflection of reality, the 'true sex'.95 Chilvers, unlike Le Mare, does not acknowledge that Huberta was initially thought of as male, but asserts her as always having been female. Yet, for nearly all his life, from the time he was 'born' at New Guelderland, he had been male. In effect the choice of Huberta is one that reads back into the hippopotamus' biography a gender that does not accord with his published past. As a female she becomes even more domesticated. She discards the 'cloak of masculinity', turned into 'a gentler . breed,'96 and by implication, in greater need of protection.

Huberta's journey south is then a narrative of an animal in search of protection. Le Mare presents it as a journey back in time, seeking this protection amidst her 'real home' in places where hippopotamus herds had lived in the past. In this 'romantic search for the land of her ancestors' she takes wrong turnings and inadvertently lands up in 'the belt of civilization'. She moves on, her 'protective instincts' forcing her further and further south, attempting to leave 'man behind her'.97 But this protection can only be achieved by a temporal reversal in an imaginary journey, from 'civilisation' in the north, across 'native territories' further south, towards a natural wilderness of the 'home of the hippo', that is ultimately not reached. What Chilvers does though is that he makes the destination appear reachable through colonial control. Drawing upon the chapter that he had written on 'Durban, and the Famous Ride of Dick King', in The Seven Wonders of South Africa, published in 1929, a large part of Huberta's journey is placed on the 'Dick King Trail'. This is the legendary story of Dick King who rode 600 miles from Durban to Grahamstown in 1842, to seek military assistance from the colonial forces stationed there to relieve the port of its occupation by trekboer forces. Evading search parties, crossing rivers in flood and escaping from wild animals, King eventually reached Grahamstown and British authority was re-established in Durban. Huberta's journey is made, by Chilvers, 'to coincide in amazing fashion with the route traversed by Dick King on his historic ride to Grahamstown.'98 Huberta, like King, may then be seen to be seeking the assistance of colonial authorities, but in the former's case from the hunters whose images are the first ones that appear in the book on the frontispiece and opposite page 22. Even though Huberta does not achieve the required protection when she is alive, Chilvers takes the story forward and presents Huberta as a martyr who had not died 'in vain'. 'For it has done far more than anything within the scope of direct propaganda to make it clear the right of the Wild to live.'99 That 'right' though is one that is to be restricted and placed within the confines of National Parks. On lands, which white farmers found unsuitable and where nagana and African hunters could be controlled, animals like Huberta would become valued for their viewability. Safely protected and controlled in the National Park, Huberta could become 'the national animal heroine of South Africa'.100

Conclusion

By the middle of 1932 Huberta's biographical journey had begun to take on substantial proportions. She had travelled from the banks of the Keiskama to Camden Town in London and had returned to take her place safely ensconced in a glass case, surrounded by a variety of mammal specimens that the Kaffrarian Museum in King William's Town had acquired in their collecting/hunting expeditions. Books were being written about her, inhabiting her body with African ancestral voices. The routes that she took in these books were southwards and backwards into history towards an imaginary originary home, and then forwards into the protection and control of National Parks.

Huberta, as she was being biographised in the museum and the publications by Le Mare and Chilvers, was being made into much more than a specimen of nature. As racial segregation began to be more firmly entrenched in South Africa, she was a symbol of territorial demarcation for people who were called 'native' (and were controlled by the Native Affairs Department) and animals who were part of 'nature'. The 'native reserves' were considered to be the appropriate habitus of the former, while the game reserves were being set aside for the latter. These game reserves were being turned into National Parks, where animals, such as Huberta, were being made available for viewing by the tourist elite.101 With their designation as 'national' they were to be owned by the nation. In this case 'the nation' was a racially exclusive one, with membership determined by whiteness. The parks were imaged as bearers of united white South African national identity, helping overcome divisions amongst the white 'races'.102 This would, no doubt, have pleased Huberta's biographer, Hedley Chilvers, immensely. What was imperative to him was that all the 'bickering' between the 'white races' cease to ensure that 'the European is to remain dominant in Africa.'103

* . This paper is based upon research conducted for a National Research Foundation (NRF) funded project based in the History Department at the University of the Western Cape: The Project on Public Pasts. The financial support of the NRF towards this research is hereby acknowledged. Opinions expressed in this paper and conclusions arrived at are those of the author and are not necessarily to be attributed to the NRF. I also wish to thank all those who assisted with research for this paper, particularly Josephine Frater, Lloyd Wingate, Joanne Parsons, George Monahadi, Stephanie Victor and Hayley Marques.

1 The Natal Mercury, 23 November 1928; 24 April 1931; 25 April 1931.

2 'New name for King's Kaffrarian Museum', Dispatch Online, 26 January 1999, accessed 27 April 2003.

3 The books specifically about Huberta, that I have managed to track down, are, in chronological order: G.W.R. Le Mare, The Saga of Huberta (Durban: Robinson and Co and the Central News Agency, 1931); Hedley A. Chilvers, Huberta Goes South: A record of the lone trek of the celebrated Zululand hippopotamus (Johannesburg: Central News Agency, 1931); Edmund Lindop, Hubert The Traveling Hippopotamus (Boston and Toronto: Little, Brown and Company, 1961); Pieter W Grobbelaar, Huberta Gaan op Reis (Human and Roussseau, 1972); Cicely van Straten, Huberta's Journey (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 1988) which was translated into Afrikaans by Anna Jonker as Die Swerftog van Huberta (Cape Town: Tafelberg, 1990); Wendy Emslie, "Huberta" (Midrand: Varia Publishers, 1992); Cicely van Straten, Huberta's Journey: A study guide (Craighall: Guidelines, 1993); Peter Younghusband, Huberta: The Hippopotamus who became world famous (Franschoek: Capricorn Publications, 2000); Meg Jordan, The Legend of Huberta (Umhlali: Ortus Books, 2001). A book that devotes almost half its content to Huberta is C.T.A Maberly and Penny Miller, The World of Big Game (Cape Town: Books of Africa, 1968).

4 Zululand Zig-Zag 'Huberta', www.zululandzigzag.co.za/huberta.php, accessed 26 July 2004.

5 S.W. Allison-Bunnell, 'Making nature "real" again: Natural history exhibits and public rhetorics of science at the Smithsonian Institution in the early 1960s' in S. Macdonald, ed., The Politics of Display: Museums, Science, Culture (London and New York: Routledge, 1998), 95.

6 P. Macnaghten and J. Urry, Contested Natures (London: Sage, 1998), 15.

7 See, for example, P. Davison, 'Typecast: Representation of the Bushmen at the South African Museum', Public Archaeology, vol. 2 (1), 2001, 3-20; C. Rassool, 'Ethnographic Elaborations and Indigenous Contestations', paper presented at the Institutions of Public Culture workshop on Museums, Local Knowledge and Performance in an Age of Globalisation, Cape Town, 3-4 August 2000; P. Skotnes, 'The Politics of Bushman Representations' in P.S. Landau and D.D. Kaspin, eds., Images and Empires: Visuality in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa (Berkeley: UCLA Press, 2002), 253-74.

8 J. Clifford, The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature and, Art (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1988), 229. [ Links ]

9 One of the best cultural studies of animals on display, but which is about a theme park, concerns itself with the politics of representation at Seaworld in San Diego, California. See S. Davis, Spectacular Nature (Berkeley: California University Press, 1997).

10 W.J.T. Mitchell, The Last Dinosaur Book, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 281-2, 77, 95-101. Mitchell's claim to the totemic status of the dinosaur relates to the ways it comes to symbolize social unity, acts as a figure of ancestry, and becomes an object of taboo and ritual. Its modernity derives from the dinosaur's emergence in the nineteenth century, the sense of modern time in which dinosaur narratives operate and the role of dinosaurs in forging a modern public citizenry (chapter 12).

11 Mitchell, Last Dinosaur, 100.

12 Others that come to mind are: Jock of the Bushveld, the dog who accompanied Percy Fitzpatrick on his adventures in the Eastern Transvaal in the late nineteenth century; Just Nuisance, the Great Dane who regularly caught the train between Simonstown and Cape Town and was enlisted into the Royal Navy at Simonstown in the 1940s; Peter the Penguin, who swam from Port Elizabeth to his home on Robben Island after being rescued from an oil slick in 2000. See P. Fitzpatrick, Jock of the Bushveld (London: Longman, Green and Co, 1907); L. Steyn, Just Nuisance - Able Seaman Who Leads A Dog's Life (Cape Town: Stewart, 1941); L. Steyn, Just Nuisance Carries On (Cape Town: Stewart, 1943); T. Sisson, Just Nuisance, A.B.: His Full Story (Cape Town: Flesch, 1985); P. Whittington, Peter the Penguin (Cape Town: Avian Demography Unit UCT, 2001)

13 The Cape Mercury, 25 April 1931.

14 These are some of the key aspects of the conceptualization of pets. See A. Franklin, Animals and Modern Culture: A Sociology of Human-Animal Relations in Modernity (London: Sage, 1999), 86-9.

15 The Cape Mercury, 25 April 1931.

16 Denver Webb, 'The Story of Huberta', unpublished manuscript (King William's Town: Amathole Museum, 1985), 5.

17 Cape Times, 22 April 1931; Daily Dispatch, 24 April 1931; Cape Mercury, 24 April 1931.

18 The Cape Mercury, 25 April 1931.

19 See, for example, George Cory, Rise of South Africa, vol 3 (London: Longman, 1932). Premesh Lalu's PhD thesis, 'In the event of Histoiy' (University of Minnesota, 2003), presents an extensive account of how the colonial historiography of the killing of Hintsa was constructed and sustained.

20 M. Lacey, Working for Boroko (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1981), chapter 3 and conclusion; A. Mager, Gender and the Making of a South African Bantustan: A Social History of the Ciskei, 1945-1959 (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 1999), 3.

21 C.J. Skead, Historical Mammal Incidence in the Cape Province, vol 1 (Cape Town: Department of Nature and Environmental Conservation, 1980), 403. [ Links ]

22 Skead, Historical Mammals, 409.

23 Daily Dispatch, 28 May 1931; F.W. Fitzsimons, The Natural History of South Africa, vol. 111 (London: Longman Green, 1920), 164-5.

24 The Friend, 27 April 1931; The Cape Mercury, 28 April 1931.

25 Amathole Museum, 'Huberta: The World's Most Famous Hippo' (King William's Town: Amathole Museum pamphlet, no date).

26 The Cape Mercury, 28 April 1931.

27 George Hangay and Michael Dingley, Biological Museum Methods, vol. 1 (Sydney: Academic Press, 1985), 203.

28 G.C. Shortridge to J. Carnell, Hon Secretary, East London Museum, 30 April 1931. Huberta File, Amathole Museum.

29 Hangay and Dingley, Biological Museum Methods, 206-7; Nicholas P. Arends and L.M.D. Stopforth, Trapping Safaris (Cape Town: Nasou, 1967), 56.

30 Hangay and Dingley, Biological Museum Methods, 4.

31 H. Ritvo, The Animal Estate (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1987), 252-3. [ Links ]

32 A.A. Adendorff to Director, Kaffrarian Museum, 27 April 1931. Huberta File, Amathole Museum.

33 B.M. Randles, A History of the Kaffrarian Museum (King William's Town: Kaffrarian Museum, 1984), 22.

34 Edward Gerrard and Sons to Captain G.C Shortridge, Director, Kaffrarian Museum, 10 August 1931; photocopy of information from personal scrapbook of Ros Hussey, daughter of Edward Gerrard, sent to Kaffrarian Museum, 10 November 1990. Huberta File, Amathole Museum.

35 Hangay and Dingley, Biological Museum Methods, ix.

36 T. Griffiths, Hunters and Collectors (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 23.

37 Cape Mercury, 15 January 1932.

38 Cape Mercury, 13 and 15 January 1932; The Star, 22 March 1932.

39 Hangay and Dingley, Biological Museum Methods, 5. Although the methods and materials used in taxidermy have altered substantially over the years, the same process of sculpting the body remains a key part in the process where 'considerable artistry comes into play'. S.T. Asma, Stuffed Animals and Pickled Heads: The Culture and Evolution of Natural History Museums (New York: Oxford University Press, 2001), 30.

40 Cape Mercury, 15 Januaiy 1932; The Star, 22 March 1932; Cape Mercury, 23 Januaiy 1932; Daily Dispatch, 20 February 1932.

41 Lindop, Hubert, 30.

42 Amathole Museum, 'Huberta'.

43 Asma, Stuffed Animals, 46.

44 Natal Mercury, 29 April 1931.

45 Franklin, Animals and Modern Culture, 69, has argued that all animals on display are 'read socially'. This is counter to the argument of B. Mullan and G. Marvin, in Zoo Culture (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987), cited in Franklin, Animals, 69, that in museum displays, animals appear as classified, fixed, objects, making it difficult for visitors to 'imagine mental states for them'. As is evident, this article leans veiy heavily towards Franklin's argument.

46 Griffiths, Hunters and collectors, 19.

47 P. Landau, 'Hunting with gun and camera: a commenta^' in W. Hartman, J. Silvester and P. Hayes, eds., The Colonising Camera (Cape Town, UCT Press, 1998), 153; Ritvo, Animal Estate, 252; W.T. Calman, Preface to J.G. Dollman, Game Animals of the Empire, Special Guide Number 1 (London: British Museum of Natural History, 1932).

48 Randles, Kaffrarian Museum, 20-1.

49 'Educational Services', Kaffrarian Museum Annual Report, 1990-91 (King William's Town: Kaffrarian Museum, 1991), 15.

50 Asma, Stuffed Animals, 44.

51 J. Hewitt, 'Captain Guy Chester Shortridge. b. June, 1880; d. Januaiy 1949', South African Museums Association Bulletin, June 1949, 299-300; F.C. Eloff, 'Shortridge, Guy Chester' in W.J. de Kock and D.W. Krüger, eds., Dictionary of South African Biography, vol 2, (Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council,1972), 663-4.

52 Nature, 9 April 1949, vol. 163, 556-7.

53 Report of the Third Percy Sladen and Kaffrarian Museum Expedition, 'Ovamboland', 7 July-9 December 1924, British Museum of Natural History (BMNH), DF 232/26; letter from G.C. Shortridge to Olfield Thomas, BMNH, 7 January 1926 BMNH DF 232/27; letter from G.C. Shortridge to Oldfield Thomas, 3 June 1925, BMNH DF 232/26.

54 Letter from Enid Shortridge to Brian Randles, 5 October 1977, Shortridge File, Amathole Museum.

55 Enid Shortridge to Brian Randles, 5 October 1977.

56 Enid Shortridge to Brian Randles, 5 October 1977.

57 F. M. Allenby, Foreword to G.C. Shortridge, The Mammals of South-West Africa, vol 1 (London: William Heinemann, 1934).

58 This quotation comes from the original 'Foreword' to 'Retrospect' that Arends wrote on behalf of the heart surgeon, Christian Barnard. Barnard, however, did not feel it was appropriate for him to give his name to such a 'Foreword' and he shortened and amended it considerably. The unpublished manuscript of 'Retrospect', together with the correspondence between Barnard and Arends, is located in the history collection of the Amathole Museum.

59 N. Arends, 'Retrospect', unpublished manuscript (1973), 25. In the 1959 Arends took a seat in the Union Council for Coloured Affairs and becoming national secretary of the Republican Coloured People's Party. The Union Council for Coloured Affairs (UCCA) was part of the package that was contained in the Separate Representation of Voters Act of 1956 that removed people who were racially classified as 'coloured' from the common voters roll. The UCCA was to 'advise the government on matters of concern specifically to Coloureds, in liaison with a Minister of Coloured Affairs and a Coloured Affairs Department.' The Unity Movement referred to the UCCA as a 'pus-blown sore on the body politics of the oppressed.' See Gavin Lewis, Between the Wire and the Wall: A History of South African 'Coloured' Politics (Cape Town: David Philip, 1987), 269-70.

60 Arends and Stopforth, Trapping, 1.

61 N.P. Arends, The Late Guy Chester Shortridge', The Mercury, King William's Town, 1 Februaiy 1949.

62 Arends, The Late Guy Chester Shortridge'.

63 Arends and Stopforth, Trapping, 31-2.

64 R. Lydekker, The Game Animals of Africa (Rowland Ward: London, 1908), 408; Fitzsimons, Natural History, 165; Shortridge, Mammals, 655.

65 The Cape Mercury, 28 April 1931.

66 Arends and Stopforth, Trapping, 72; Arends, 'The Late Guy Chester Shortridge'.

67 The Natal Mercury, 25 April 1931; Cape Mercury, 28 April 1931; Cape Mercury, 2 May 1931; Daily Representative (Queenstown), 27 April 1931.

68 Letter from 'Also Disgusted' which originally appeared in the Rand Daily Mail and is re-printed The Cape Mercury, 2 May 1931.

69 The Friend, 29 April, 1931.

70 Daily Dispatch, 28 May 1931.

71 Daily Dispatch, 28 May 1931.

72 I concentrate much more on the Chilvers book as it was much more widely distributed. It also became the basis of many of the Huberta biographies in the future.

73 The Natal Mercury, 23 November 1928; J. MacKenzie, The Empire of Nature (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988), 241. Nagana is a Zulu word for cattle-sickness.

74 L. White, Speaking With Vampires: Rumour and History in Colonial Africa (Berkeley: UCLA Press, 2000), 228-9.

75 D. Bunn and M. Auslander, 'Owning the Kruger Park', Arts 1999 (Pretoria: Department of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology, 1999), 60.

76 The Natal Mercury, 23 November 1928.

77 C. Selwyn Stokes, 'The National Parks of South Africa' in Chilvers, Huberta, 157-8, 126-7.

78 Chilvers, Huberta, 20-24.

79 Chilvers, Huberta, 103-106.

80 Chilvers, Huberta, 106-7.

81 Chilvers, Huberta, 104.

82 Le Mare, The Saga, 9, 20; Chilvers, Huberta, 28-30, 73, 75-77, 83.

83 Chilvers, Huberta, 29.

84 Chilvers, Huberta, 58-9.

85 Chilvers, Huberta, 59-60.

86 Hedley A. Chilvers, The Seven Wonders of Southern Africa (Johannesburg: Administration of the South African Railways and Harbours, 1929); Hedley A. Chilvers, Out of the Crucible (London: Cassell and Company, 1929); Hedley A. Chilvers, The Seven Lost Trails of Africa (London: Cassell and Company, 1930); Hedley A. Chilvers, The Yellow Man Looks On (London: Cassell and Company, 1933). A short, glowing biography of Chilvers as an accomplished historian who undertook 'painstaking research' and wrote in a 'vivacious' style appears in the first volume of the Dictionary of South African Biography. See F.R. Metrowich, 'Chilvers, Hedley Arthur' in W.J. de Kock, ed., Dictionary of South African Biography, vol 1 (Pretoria: National Council for Social Research, 1968), 167-8.

87 Chilvers, Yellow Man, 214.

88 Chilvers, Yellow Man, 231.

89 Chilvers, Crucible, 1, 7-8; Chilvers, Seven Wonders, 251-2.

90 Chilvers, Seven Wonders, 268-271.

91 L. Switzer, Power and Resistance in an African Society (Pietermaritzburg: Univesity of Natal Press, 1993), 222-3; Saul Dubow, Racial Segregation and the Origins of Apartheid in South Africa, 1919-36 (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1989), 111119.

92 Chilvers, Seven Wonders, 251.

93 Cook's Tour of South Africa (brochure) (1935), 11.

94 Le Mare, The Saga, 3. In another case of a wandering hippo in 1956 a similar set of events occurred. Harold turned out to be female and was renamed Haroldina (The Star, 23 July 1956). In the hippopotamus file of mammal section of the Amathole Museum there are two other newspaper clippings relating to wandering hippopotami in South Africa, and both are female. The one, unsourced, refers to Mina, Pretoria's 'famous wandering hippo cow', while the other was named Winnie, 'a renegade hippo' that was 'causing havoc to farms in the Somerset East District.' (Eastern Cape Weekend, 23 January 1999)

95 Webb, 'The Story', 1.

96 Le Mare, The Saga, 3.

97 Le Mare, The Saga, 3-4

98 Chilvers, Huberta, 65.

99 Chilvers, Huberta, 103.

100 Chilvers, Huberta, 17. The notion of National Parks changing the market value of animals from 'edibility' to 'sporting characteristics', and then 'viewability' is drawn from MacKenzie, Empire, 267.

101 MacKenzie, Empire, 267.

102 J. Carruthers, The Kruger National Park (Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 1995), 60-66.

103 Chilvers, Yellow Man, 223.