Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.30 no.1 Cape Town 2004

The contested nature of colonial landscapes: historical perspectives on livestock and environments in the Transkei1

Jacob Tropp

Middlebury College

Introduction

This article explores the meaning and legacy of conflicts over livestock management and state environmental control in the colonial Transkei. Most writings on such conflicts in the twentieth century Eastern Cape have focused on the more recent era of state betterment planning or have limited analysis to the confines of African commonages and 'locations'.2 Despite their immense contributions, such perspectives have tended to obscure the significant contestations over resources and meaning which surrounded the state's initial takeover of local landscapes and the imposition of new environmental categories during the formative development of colonialism in the region.

As the Cape Colony extended political control over local African societies in the late nineteenth century and established the Transkeian Territories, it simultaneously launched a comprehensive regime of local forest conservation.3From the 1890s onwards, as officials began systematically surveying and reserving particular natural areas as state forests, livestock owners across the region contested both the government's definitions of local landscapes and its efforts to restrict livestock access - through forest fencing and stock trespass regulations - according to these new mappings. As land and grazing pressures increased over the early twentieth century, state forest conservation and livestock exclusion policies became the centre of intensifying conflicts over the government's maldistribution of forest lands and its alienation of potential grazing resources amid popular experiences of intensifying scarcity. Reflecting on these changes and tensions offers fresh perspectives on the nature of state-peasant environmental relations in the region as well as on the meaning of local landscapes in popular livelihood practices, past and present.

Historicizing Livestock Landscapes

From the perspective of forest officials in the late nineteenth century, Africans' livestock represented some of the most intractable obstacles to conservation efforts in the Transkei. As colonial authorities attempted to demarcate and regulate access to state forest lands, domestic animals seeking shelter or sustenance in these natural areas presented perpetually elusive targets of official control. Along with state officials' regular condemnations of Africans' own direct impact on local forest environments, they also repeatedly assailed Africans' livestock as agents of deforestation and soil erosion. Particularly beginning in the early 1890s, foresters aggressively expanded their efforts 'to keep out all native cattle, goats, sheep and horses' from the valuable timber forests of the Transkei, 'in fact to close them, as far as practicable, to natives'.4 Yet as the government developed and deployed policies to exclude forest grazing over the next two decades, their efforts were mired in two unavoidable realities: African livestock managers asserted competing interests in forested areas, and it was difficult - if not impossible - to control thousands of animals streaming in and out of newly proclaimed government forest reserves.

As colonial forest regulation expanded in the 1890s, livestock owners inhabited a region comprised of extremely diverse landscapes.5 Just below the great escarpment, lining the historical boundary between the Transkei and the colony of Basutoland, is a highland zone ranging from 1,300 to 2,000 metres, which included areas from rolling grass-covered country to treeless mountains. In the central inland districts in the early colonial period, sizeable afro-montane forests stretched along the seaward side of the lesser escarpment (highest altitude of about 1400 metres).6 Below this escarpment lies an undulating lowland plateau stretching down to the beginning of the coastal belt at roughly 700 metres. While generally flat, these lowlands are occasionally dotted with hills and mesas in the southwest, become much more mountainous as one travels northward, and are dissected by deep river valleys and streams in certain areas. This plateau receives much less precipitation than either the escarpments to its west or the coastal belt to its east, affecting the vegetation in the region at the onset of colonialism: deciduous woodland and scrub dotted the grasses of the flatlands, while denser clusters of various types of trees crowded river and stream banks. The coastal belt added even greater levels of complexity to the Transkei's vegetation in the late nineteenth century. From the lowland plateau to about 300 metres lay a strip of coastal scarp forest, which then connected to a series of lower coastal forest types, some quite extensive, becoming progressively more diverse and subtropical in the northern parts of the coast towards the Natal colony border.7

Since access to forests and woodlands thus varied greatly from one locale of the Transkei to another, it is difficult to generalise about their role in Africans' livestock management strategies at the turn of the century.8 However, contemporary sources do suggest that for many farmers in many different locales wooded lands were vitally important to the care and development of their animals. In the words of one headman in Pondoland in 1914: 'The forests were the mainstay of the cattle.'9 Forests and woodlands not only could provide access to streams, fertile grasses, and tree fodder, but also served as important shelters during difficult climatic shifts.10 Even as magistrates and foresters at the turn of the century worked to curtail the 'trespass' and 'devastation' of Africans' cattle, sheep, and goats, they could not ignore the significance of regular forest and woodland access to many local farmers and their livestock. When colonial authorities first debated methods of penalizing African stockowners for allowing their animals to graze in reserved forest areas in the early 1890s, Chief Magistrate Henry Elliot wanted to make sure that his superiors back in Cape Town understood the meaning of such restrictions in daily practice:

There is no other act that irritates and excites a native so much as driving off his cattle. It must be remembered that in cold driving rains (not infrequently mixed with sleet) such as usually visit these territories every spring, cattle will rush so madly before the storm as to be quite beyond the control of herds: in fact herds themselves would often perish if they attempted to remain exposed upon such occasions. Cattle naturally seek their natural shelter.11

Two years later one magistrate similarly explained that 'the cattle fly for protection to the Forests' during the spring rains, adding that 'if deprived of their natural shelter serious losses would result' - a point reiterated periodically by officials over the years, albeit with diminishing sympathy for African stockown-ers' forest interests.12 Similar comments by Africans themselves in this early period occasionally surface in archival records: in 1908 in the Tsolo district, for instance, one headman explained before the district council how throughout his location 'stock run to the Mimosa thickets for protection in cold weather.'13

Besides their value as shields from the cold rains, forests were also especially important during the vagaries of other seasons, such as excessive summer heat, when animals sought shade among trees and bushes, and dry winters and periodic droughts, when the valued watering places of many forest areas became vital.14 During such dry periods, grasses and other vegetation in forest areas were also often the most palatable grazing and browsing sources in many locales. One elderly man in the Baziya area of the Umtata district, for example, explained to me how during particularly dry spells in the early part of the century the nearby KwaMatiwane forests were the choice destination for cattle grazing when grasses in the open veld were in poor condition:

during the drought seasons, people would go with the cattle and sheep and stay there by the forest, put some shacks, you know ... for accomodation. Stay there, grazing their cattle there, cattle and sheep, milking the cattle there with calabashes ... Even we, when we'd go there, would just go to those shacks if you feel hungry and ask for food from them, and you'd be given sour milk there because there's plenty of milk. And when the rain comes, and grass has grown up amongst our areas here, they'd demolish everything there and come back again.15

Forest officials were especially chagrined by such practices over the years, often complaining about the general increase of what they viewed as livestock trespass and tree damage during the winters and droughts, when many stock-owners took advantage of prime resources in the forest reserves. During the dry season of 1908, for instance, District Forest Officer A.G. Potter reported with dismay that African stockowners from far and wide employed local social and economic networks to take advantage of the more fertile grasslands in the St. Mark's and Engcobo highland forests: 'the stock "belonging" to natives living adjacent to a forest reserve increases miraculously during the winter months, ... a man who may not have a fowl in the summer will possess great flocks and herds when the forest-grazing is sought after.'16

The importance of forests to many stockowners in the early colonial period is further suggested by the associations interview informants in the late 1990s, originally from the Umtata, Tsolo, and Engcobo districts, consistently made between forest grazing and past economic prosperity. Nozolile Kholwane commented on her youth in the Tsolo district mountains: 'At those times we had big herds of cattle, because we lived near the forests. We were not on open flat-lands. We had cattle, sheep, and we were getting milk from our cows.'17 Others stressed the high quality and abundance of the forest grasses: 'We took our cattle into the forest, where we'd feed them in long grass, and you'd only see the horns of the cattle.'18 'The grass was so tall', another explained, 'and when you were milking, the milk would fill up a big bucket. They were sleeping on grass and waking up on grass.'19 Tsikitsiki Nodwayi of the Tabase area of the Umtata district recounted the early colonial period in this way:

If you want me to tell you about the old days, we were controlling our lives. We were not dependent on whites . We depended on our livestock. If you wanted money, you would shear the wool from the sheep and sell it to the whites and get money . If you had two cattle, you'd accompany them to the forest and they would give birth to others. You'd look after your sheep. That's how we lived.20

These similar narratives, connecting people's historical access to forest areas for their livestock with economic self-sufficiency and resource bounty, in part reflect individuals' contemporary perspectives on their situations of relative poverty and scarcity.21 Yet taken together, they further recall the unique value forests historically represented for many stockowners in the Transkei's earlier years.

Conflicts over Grazing: Fences, Trespasses, and Traps

Given the persistent importance of forests to many local stockowners and herds, foresters were at pains throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to control the trespass of Africans' cattle, sheep, and goats. In the absence of any comprehensive regulations on the matter in the late 1880s and early 1890s, foresters and magistrates routinely devised their own methods of livestock restriction and often clashed with local communities, and each other, in the process. In late 1889 in the Engcobo district, for example, Resident Magistrate Arthur Stanford complained that local foresters' policing and intimidation tactics were 'likely to cause much uneasyness [sic] amongst the Natives.' While Stanford was unaware that any forests had been officially demarcated in the area around the Emjanyana river, he had been told by the local forester that, with orders from his superiors, 'the forest had been beaconed and the natives warned to keep their stock out.' The headman in the region offered a more graphic description: local men had been told to keep their cattle out of the forest or 'else the stock found there will be shot.'22

While the threat of having their cattle shot was perhaps unusual, Africans across the Territories faced forest officers and guards' more regular efforts to restrict livestock access by impounding and exacting trespass fines over the early 1890s.23 In 1890 the new forest regulations restricted the grazing of livestock in any fenced-in forest area without prior official permission.24 Based on this law, foresters in some locales occasionally seized Africans' livestock and drove them to the sole impoundment centre in each district during this period - the district magistracy. In addition to feeling the direct financial burdens of trespass and impoundment fees, African stockowners also had to bear the economic disruptions and inconveniences of this system. In 1893 Chief Magistrate Elliot highlighted such concerns to urge that the colonial administration approach the entire question of penalizing for stock trespass in government forests 'thought-fully and cautiously': 'to drive a man's stock to the Magistracy often a distance of twenty or thirty miles, would mean loss to him of the young calves which are always kept at the kraals, and that his children would be deprived of milk for several days; even the driving money for a long distance would be a considerable item.'25 Even as the pound system was expanded in the late 1890s and early 1900s, the distance men would have to travel to recover their livestock from government pounds was still often considerable.26

Of more direct concern to most officials by the turn of the century was the overall impracticality and ineffectiveness of such deterrents to forest use. One of the greatest obstacles foresters faced in their attempts to curb African grazing practices was the limited fencing of government forests. Lacking sufficient materials and personnel to erect physical barriers around most reserves, colonial authorities could have only a marginal impact on the mass pursuit of forest graz-ing.27 Forest officials were quite frustrated by the situation throughout the 1890s, as they continually encountered what they considered inadequate financial support from the colonial administration. Throughout his tenure as Transkeian Conservator, C.C. Henkel argued time and again for the need to construct greater physical impediments to Africans' livestock. As the initial demarcations were undertaken in many districts, Henkel regularly pleaded for budgetary support for the erection of fences around the perimeter of these newly acquired reserves. Fencing, he urged, was the only sure way to check the 'injurious effect' and 'incalculable lot of damage' regularly caused by cattle, horses, sheep, and goats progressively nibbling away at the young regrowth in forest lands.28

Yet, despite the volume of Henkel and other officials' appeals, little fencing had been completed by the end of the decade. Wire barriers had been erected around many of the small yet growing plantations and nurseries, but the overwhelming majority of indigenous forests remained physically open. When Henkel retired, the new leader of the conservancy quickly abandoned some of his predecessor's renowned idealism and adopted a more pragmatic approach. Given the impracticability of erecting barriers along the borders of all Transkeian forests, fencing would generally be confined to state-owned plantations and the past practice of placing beacons around forest perimeters would have to suffice for demarcated areas. Financial pressures, in fact, would continue to limit fencing to plantations for many years to come, confounding many forest officials' interests in restricting livestock grazing more comprehensively. Not until the late 1930s, under the aegis of the Native Trust regulations, would the state administration begin to commit resources more seriously to segregating designated grazing and forestry areas with physical barriers.29

With limited fencing available by the turn of the century, conservators increasingly pushed for more aggressive policing of state-owned reserves to check livestock trespass. Foresters' actions on the ground were supported by new regulations concerning the depasturing of Africans' livestock in 1903. Under Proclamation 135, fenced-in forest areas - tree plantations and nurseries for the most part - were now off limits to livestock grazing except by acquiring a temporary, tariffed licence. For the vast majority of unfenced forest reserves, Africans were allowed to graze livestock in non-wooded areas, as long as they obtained a free grazing licence from a government officer specifying the exact forest to be used and the number of animals allowed. The two major exceptions to these 'privileges' were that goats - universally condemned by conservation advocates - were expressly prohibited from grazing in wooded areas of demarcated forests, and the Transkeian conservator was also empowered to close particular forest areas to grazing for conservation reasons, pending governmental approval. In cases where demarcated forests had been so closed, police and forest officers were empowered to seize and impound livestock found trespassing.30 Over the next few years, these restrictions and foresters' diligence led to the impoundment of thousands of Africans' cattle, sheep, and goats.31

It was this problematic combination of factors - incomplete fencing of forests amid more aggressive policing of livestock movements - that generated greater conflicts with African stockowners over the 1900s. The problems surrounding fencing became embroiled in deeper disputes about the government's restructuring of rural landscapes and the contradictions such practices posed for African communities. A conflict over stock 'trespass' in the Amanzamnyama forest reserve of the Mount Frere district reveals how some of these tensions were developing at the turn of the century. When the forest was first surveyed and demarcated in the mid-1890s, Bhaca communities in the area were taken aback by the extent to which the reserve would swallow up their farming and grazing lands. Makaula, the Bhaca paramount chief, appealed to the chief magistrate of East Griqualand, Walter Stanford, to intervene, who responded by temporarily halting the fencing which had begun around the reserve's perimeter.32 Over the next few years some additional fencing was added, but large gaps still existed along many parts of the reserve boundary.

For local stockowners such incomplete barriers presented a mixed blessing. In the first years following demarcation in the late 1890s, as restrictions on livestock were only beginning to be regularly enforced in the area, stockowners exploited the gaps as access points for their animals to continue to depasture in the reserve's grasslands. But as local foresters began more systematically penalizing owners for stock trespass in the early 1900s, the lack of complete fencing became a nuisance. In early 1902, the magistrate at Mount Frere, W. Power Leary, investigated a dispute erupting along the reserve borders between African stockowners and the local forester. Many of the men living closest to the reserve, 'having all their grazing lands taken from them' through the forest's demarcation, were now facing fines when their stock wandered into the reserve:

The complaint as far as I could gather is that the Reserve is not fenced, and where fenced there are open gate-ways through which stock stray onto the Reserve, which is then seized by the Forester and trespass fees demanded from the owner. On my arrival at the Forest Station I found a number of horses being released by the owners, at 1/6 per head, for having trespassed on the Reserve.33

As many Bhaca stockowners asserted in this dispute, without fences 'protecting' forest reserves from livestock trespass, there was nothing 'protecting' African farmers from costly penalties when their animals inadvertently wandered into grasslands across invisible reserve boundary lines.

From the early 1900s onwards, as forest officers more regularly seized and impounded Africans' livestock across the Territories, tensions arising from unfenced forest reserves became increasingly common and widespread. In some of the inland mountain regions of the Territories, where the difficult terrain resulted in limited fence work being completed, African livestock owners petitioned and complained to local officials about what they described as governmental hypocrisy. In the highlands of the adjoining St. Mark's and Engcobo districts, for instance, the practice of grazing goats in local forest reserves was often an intentionally critical response to the government's impractical and contradictory application of forest conservation and impoundment laws. As one engineer working around the Mkonkoto forest reserve in the Engcobo district explained in 1908, local African residents asserted that they 'have a right to let their goats graze and browse where they please as, when the Reserves were laid out, a distinct promise was made to them that the Reserves would be fenced, which has, apparently, not been done.'34

By the late 1900s, facing such day-to-day resistance to forest grazing restrictions, officials pursued what they viewed as a compromise. While foresters would only police wooded areas of unfenced demarcated forests, Africans could use non-wooded portions for their livestock.35 In 1911, Government Notice 668 standardized such practices, prohibiting Africans' stock in wooded areas of government reserves.36 Forest officials viewed this measure as a reasonable means of conceding to some of the resource needs of rural Africans while shoring up the protection of the Transkei's trees. For African stockowners, however, although the new policy made some grasslands available within demarcated boundaries, it did little to alter the basic problems arising from unfenced forest reserves. Despite the law's imposition of invisible boundaries separating non-wooded from wooded forest areas, there was nothing to stop cattle from wandering from one to the other. Without fences around the government's trees, and with foresters and guards more rigorously patrolling wooded areas, stockowners now faced an even greater likelihood of their animals being seized and impounded for trespass.

This point was made most forcefully by a deputation of Mpondo leaders from the Lusikisiki district soon after the law took effect. In September 1911, Chief Marelane spoke for the group at a meeting with the chief magistrate in Umtata:

There is a new law about cattle grazing in Forests, and now the forests are being treated like cultivated lands. We have therefore come to ou[r] father because most of us live amongst forests, and the people are always uneasy about their cattle as they have built their kraals alongside the forests. The prayer of the Chief and the people is that these demarcated forests should be fenced, otherwise they are a trap.37

The following year, leaders from the Tsomo, Kentani, and Tsolo districts at the Transkeian Territories General Council (TTGC) moved that Government Notice 668 be immediately withdrawn, as people across the Territories were being 'throttled' by the new restrictions. Even Chief Magistrate W.T. Brownlee recognised how stockowners throughout the Transkei were indeed being trapped by government policies. In 1912 he noted that the combination of inadequate fencing and forest guards' more vigorous pursuit of grazing offences 'has caused heart burning in many districts, particularly where small patches of bush in the middle of the pasturage are demarcated. It is easy to realise that a man of moderate means, whose kraal is a short distance from a forest, finds it difficult to prevent his stock from entering it ...'38 However, even though some authorities might privately acknowledge such problems faced by African stockowners, officials' growing consensus behind forest conservation overruled any interest in relaxing forest access regulations.39

From the early 1910s onwards, colonial policies and the government's only partial ability to enforce forest restrictions together placed African livestock owners in a peculiar situation. While authorities could use their power to limit grazing access and penalise Africans for stock trespass, they were not in a position physically to prevent such offences from occurring. And despite many Africans' demands for more effective barriers around government reserves and the loosening of restrictions imposed over the preceding decades, stockowners themselves were now ultimately liable.40

Growing Tensions over the Meaning of Forests

While African stockowners adjusted to the government's expanded policing of livestock in the 1900s and 1910s, they also felt another uncomfortable reality of state conservation policies: the demarcation of unforested lands and their reservation as 'forests'. In demarcating and managing reserves throughout the Transkei, forest officers consistently employed a liberal interpretation of what they termed forest 'potential': more often than not grasslands and other areas without trees or shrubs were purposely included within demarcation boundaries in order to protect trees from potential veld fires and to reserve lands for the future expansion of tree crops. Yet for stockowners across the region, such treeless grasslands represented readily available and seemingly unused resources that could serve vital livelihood needs in the present. In the 1900s and 1910s, these clashing priorities added further sources of popular discontent to ongoing resource disputes.

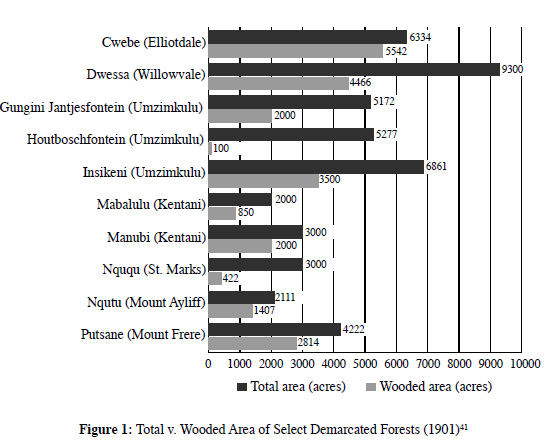

Problems with the state's administration of grazing areas originated with forest officials' initial demarcation of rural landscapes. In one of the few official documents to describe in detail the composition of forest reserves for this early period, a 1901 departmental report reveals the extent to which state-controlled forests in many parts of the Territories actually comprised vast tracts of treeless lands. As Table 1 shows, several of the largest forests reserved by the government during the previous decade contained only a fraction of actual wooded area, amounting to a difference of thousands of acres in certain cases.

According to official estimates, of the entire 137,208 acres of forest reserved by the Forest Department by 1901, only 82,719 was actually wooded; by 1904, after a new round of demarcations was completed, a little less than two-thirds of the 195,349 acres of government forest lands consisted of trees.42 As for additional areas reserved for government tree plantations, in 1906 the department reported a total of 11,436 acres set aside for such purposes in the preceding decade, but only 3,280 acres of this ground was defined as 'actual' plantation.43After the Forest Department expanded its landholdings in the Transkei by placing substantial areas under demarcated status in subsequent years, this general pattern was only exacerbated. Comparative data are unavailable for the 1910s and 1920s, but by 1936, officials reported that of the 266,719 acres of government forest reserves in the Transkei, some 106,040 acres, or nearly 40 per cent, fell under the categories of 'unafforested' or even 'unsuitable for afforestation'; in state-owned plantations, nearly 16,000 acres in the conservancy were unwood-ed.44 Such disparities between the virtual forests demarcated and reserved by officials and the actual presence of desirable forest pasture increasingly aggravated relations between the state and African stockowners in the early twentieth century.

As authorities themselves readily acknowledged, officials were particularly imaginative in declaring known grazing areas to be forests during the initial period of demarcation in the 1890s and 1900s. In 1908, for instance, Chief Magistrate Arthur Stanford confidentially explained to the Bizana district magistrate the practice of demarcation over the preceding decades:

There has been a tendency on the part of Forest Officials to try and include large tracts of land outside the forests on one pretext or another, such as including three or four detached Forests in one demarcation and through this in many districts the Natives have lost large tracts of grazing land, of which the Forest Dept in many instances makes no use of but to hire out to Europeans which causes a feeling of irritation amongst the Natives.45

It was this creative and expansive interpretation of forest reservation which was critically targeted by the editor of the Xhosa-language newspaper Imvo Zabantsundu in 1906. Responding to the similar appropriation of grazing lands by the Forest Department in the Eastern districts of the Cape Colony, the paper argued that a 'great injustice' was being done to Africans 'by unsympathetic administrations which, without reference to the people, proceeded to take acres and acres of ground, on which there was not a single tree, and called these forests.'46

Imvo's critique of the state's remapping and regulation of local landscapes was reinforced by stockowners in various Transkeian communities during these years. In the Mount Frere district in the early 1900s, for example, the Resident Magistrate described some Bhaca stockowners' frustration with the government's absorption of location commonage resources into a restricted forest area: 'Previous to demarcation this land was grazed over by the men living near, and they consider it a hardship not to be allowed to graze their stock on the parts of the Reserve not being cultivated and not used, at present, by the Forest Department.'47 This particular emphasis on unused forest lands may in part have been strategic. In protesting new restrictions on their grazing rights and the costs of repossessing impounded livestock found trespassing, local men may have 'tactically phrased' their complaint to embolden their case with authorities, much as Donald Moore has described the actions of peasants negotiating access to Nyanga National Park in contemporary Zimbabwe.48 Yet the broader criticism of the state's alienation of grazing resources was increasingly echoed elsewhere.49In 1908 in the St. Mark's district, for instance, a group of African men 'strongly protested any action by the Forest Department whereby their stock would be prevented from grazing' on the Indlunkulu forest reserve, considering 'that they have already been deprived of an extensive portion of veld' by the government's establishment of a neighboring plantation. As Chief Magistrate Arthur Stanford revealed in his report on the situation, the scarcity of grazing in the location was due, in part, to the 'considerable amount' of grazing land absorbed by forest demarcation: of some 1,200 acres total, the Indlunkulu actually only contained about 100 acres of wooded forest.50 A few years later at the Pondoland General Council, representatives from the Western Pondoland districts likewise complained that local grazing areas - 'nice bare patches between some of the forests' - had been inappropriately 'considered as part of the forests'. For Chief Mangala of the Libode district and other councillors, the situation was confounding: 'when forests were demarcated the land between them had been included in the demarcation. He did not know whether it was intended that forests should increase in size. Trees which he had seen on the outside of the forests when he was a boy were still in the same place and the forests had not spread at all.' If the government did not plan to make use of treeless forest lands, then why shouldn't these grazing resources be opened to public use?51

Such disputes were exacerbated by the early 1910s as officials began a new round of demarcations in many locations. Aware of the popularly resented inclusion of 'large tracts of grass land' in previous demarcations, some Native Affairs authorities, as early as 1910, had proposed placing a cap - a 20-yard maximum distance between wooded areas and the outer boundary of a forest - on the Forest Department's liberal interpretation of forest lands.52 As demarcation officers went about their work over the next several years, however, they were given the discretion to forego such detailed calculations and irregularly shaped expanses of land for the sake of forest tracts which could be more easily and efficiently measured, surveyed, and marked with beacons.53 In many cases they did just that, much to the frustration of local African stockowners. In 1916, for instance, councillors from the Libode and Port St. John's district brought forward popular complaints that forest beacons were placed at great distances from the actual wooded areas of the reserves.54 Such complaints and the grazing problems posed by colonial forest policies, expressed sporadically in this formative era of demarcation, would only grow in scope and intensity as pasture scarcity became more severely symptomatic of the Transkei as a whole in the coming years.

Pasture Decline and the Expansion of Forest Conflicts

As stockowners in the Transkei, as in other African reserve areas in South Africa, experienced mounting socio-economic and ecological constraints during the 1920s and 1930s, they more regularly and directly contested the Forest Department's continued alienation of grazing resources in the face of popular suffering. While local social and environmental conditions were not simple reflections of the South African state's increasing concerns about overstocking and soil erosion in the reserves, grazing pressures were indeed intensifying in many parts of the Transkei over these years. One reason for this was the overall increase in livestock numbers across the Territories, peaking in the late 1920s and early 1930s after recovering from the devastating impact of East Coast fever in the early 1910s. Other writers have analyzed the multiple causal factors in this trend, including changes in veterinary practice, the cheap price of cattle relative to migrant labourers' wages at this time, and the willingness of increasingly fragmented rural economies and smaller rural households to invest in livestock.55Such changes in animal populations had significant impacts on the quality and availability of pasture over this period. Following the tremendous losses to disease in the early 1910s, pressure on local pasturelands diminished for several years; from the early 1920s onwards, however, as livestock numbers began to regain their pre-fever levels, the quality and availability of commonage grazing areas began to decline more rapidly.56

These developments, of course, did not impact on everyone equally. Although figures on cattle distribution for the colonial period are incomplete, highly problematic, and vary tremendously between different administrative units and communities, it has been estimated that by the 1940s roughly half of the Transkei's households owned no or a negligible number of livestock - the majority of stockowning households possessed only a few animals each, about 10 per cent owned enough stock to be able to support a 'middle peasant' existence, and the ownership of sizeable herds was concentrated in the hands of a relatively small class of wealthier peasants.57 As grazing pressures intensified from the 1920s onwards, those more prosperous owners of larger herds were better able to cope with the losses associated with these rapid social and ecological changes. For the majority of stockowners, however, the loss of reliable grazing areas was a serious threat to the resources in which they had invested the most. In all cases, the decline in commonage grasses drove stockowners to seek out more intensively any available grazing areas for their animals. And in this pursuit, unused pasturage in government-declared forests was an increasingly desirable, and contested, resource.

As grazing in the locations diminished, many African stockowners herded their animals onto demarcated forest reserves and plantations more regularly. One headman from the Qumbu district described the growing attraction of forest lands as location resources declined in the late 1920s:

Round about these demarcated forests were Native kraals, and sometimes there was a drought and the different small streams in the location had no water, but there was water to be found in the wooded forests ... It often happened that the only grazing for cattle was on the commonage close to the forests and the cattle were generally driven to the grass near the forests.58

Dabulamanzi Gcanga recalled how local mountain forests in the Engcobo district in the early 1920s contained both more fertile and more extensive grazing areas than in the locations: 'There's better grass, there's better grass there. And here there are lands, and old people thrash us when the animals trespass on their land. So we had just to go up to the mountain.'59

Increasingly over the late 1920s and early 1930s, such vital interests in forest access led herders to break illegally into fenced-in government plantations and forest areas. During the first few decades of state forestry in the Transkei, amid public outcries regarding the government's unfenced forests serving as livestock 'traps', many stockowners and herders also resented the fencing off of grazing areas and occasionally risked impoundment and trespass fines by slipping animals into fenced forest areas.60 But by the late 1920s and 1930s, breaking fences and herding animals through them became a much more systemic response to pasture decline and scarcity as well as a weapon of protest against the government's withholding of valuable resources. Foresters more regularly complained about African men and boys cutting up, removing, and pulling apart fencing wire to let animals into restricted areas. Such practices, in fact, mitigated against officials expanding the fencing of reserves during this period, as it would be impossible to prevent fences being damaged again and too costly to continually replace them.61

One informant who grew up in the Manzana area of the Engcobo district in the 1920s and 1930s, Polisile Maka, recalled some of the deeper problems underlying this rise in forest incursions. Beginning in the late 1920s, people from the Manzana location protested the government's fencing of some commonage grazing lands to protect a municipal plantation at nearby Engcobo. As Maka explained: 'They used to break it [the fence], because our stock would be taken to the pound in town. They would say you must pay - we paid a lot. But the place is ours.'62 As this example suggests, stockowners in various locales were particularly resentful of the government's costly penalizing of their attempts to secure sufficient grazing for their animals. At a time of mounting economic and ecological pressure, more and more livestock herders regularly dismantled the boundaries imposed by colonial authorities, for both material and symbolic reasons.63

While trespassing increased on the ground, many prominent stockholders attempted in the late 1920s and early 1930s to dilute the severity of grazing restrictions through more formal political means.64 During the TTGC's 1929 session, for instance, several headmen expressed popular concerns to colonial magistrates in particularly vivid terms. 'This is one of the most disturbing questions to the people,' a St. Mark's councillor explained. 'Our cattle are being impounded when they graze on these grasslands, because the beacons are far from the forest.' Josiah Xakekile of the Butterworth district added his own story of meeting with people in his area prior to the council session and hearing their complaints of cattle and goats also being impounded for roaming beyond the beacons. 'The people have been treated unfairly in this matter,' he asserted. 'It amounts to expelling people from their present kraal sites.' Another headman from the Nqamakwe district called attention to popular frustration with the government for increasingly penalizing for trespass when the forests were not adequately fenced. 'If there is anything the people have specially requested me to attend to, it is this . In order that we may live in peace we think the Government might fence these lands. As soon as stock has shown its nose beyond the beacon stone it has been impounded.'65 Such appeals to government - to erect proper barriers around actual wooded areas and allow local people to exploit the unused and scarce pasture within reserve boundaries without the threat of seizure and fines - were a regular feature of council debates for years to come.66

With greater obstacles to livestock mobility and mounting pressures on location pastures during these years, stockowners also campaigned for a more beneficial reassessment of forest demarcations. This development is especially noteworthy considering the nature of state discourse criticizing African resource management during this period. At the same time that government officials increasingly pointed their fingers at African peasants for overtaxing the 'carrying capacity' of location soils,67 African men consistently called into question the very extent and nature of that capacity. By repeatedly urging state authorities to readjust forest boundaries, they invoked alternative visions of the landscape available for livestock grazing. While forest officials defended the extent of reserves under their control more intensely, stockowners on the ground contested the government's categorization and control of land in response to deepening ecological strains in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

In many cases, individuals and groups contested the Forest Department's plans to extend or create new wattle plantations by appropriating additional commonage grazing areas.68 There was no easy consensus among stockowners or even among different economic strata on this issue, however. In prioritizing their needs for wood versus grazing lands, different individuals brought into play their varied wealth in cash and cattle, their access to wood supplies, and the environmental conditions of local pastures.69 Some of these dynamics are evident in the critique of state forest management leveled by one anonymous stockowner in the Emjanyana area of the Engcobo district in 1932. In a letter written directly to the chief magistrate, the individual protested the allocation of commonage lands to the production of state-owned trees:

I appeal to you to use your power & prevent further plantations being planted at the Enkobongo & that the present fence now under construction be Taken [sic] down & also the one adjoining the Emjanyana asylum which are not necessary there being quite enough plantations to supply the requirements of our needs, the fore said is robbing us of pasture for our stock which is becoming so limited & to prove to you I wish you could see How [sic] the mountain is cropped down, & if what is now under construction is going to be continued then our poor starved stock will all die & bringing dire irritation on us. Admittedly our stock is of no value but that is our only means of Security which assists us in Times of Starvation & as we can hardly make a living in Johburg [sic] we must rely on our stock to support us. . . . There are lots of plantations we can go to Engcobo & many others but if we Have no stock we wont ever be able to go to the close ones. The Emjanyana reserve has a very big piece of ground & I dont see why they should take our pasture to plant trees when they have lots of waste ground.70

Having close access to wood sources, and possessing the animal power to transport these supplies, such stockowners were more concerned with the welfare of their cattle and the deterioration of local commonage pastures. What stands out in this particular case is the final emphasis on the hypocrisy of official claims to require additional land for afforestation.

Besides such efforts to halt further state appropriation of pastures, many African political leaders in the late 1920s and 1930s also increasingly worked to scale back the existing boundaries of demarcated forest reserves and thereby free up more grazing lands in their communities.71 At the 1925 session of the TTGC, councillors from the St. Mark's and Xalanga districts complained about the shortage of pasture, urging that land situated between the beacons of demarcated forests 'should revert to the commonage, so that it could be used for the benefit of people's stock. If the Forest Department gave up that land they could supply land to the people who had none.' One headman from the Xalanga district was even more emphatic: 'a lot of land had been taken from the people. Why should they pay taxes to the Government and the Forest Department because when the beacons were fixed up the land was there, but the Forest Department was not prepared to give it up?'72 A few years later, at the 1929 session, similar complaints were lodged again, and one councillor moved that the Forest Department reset the beacons marking all government reserves so that all non-wooded portions were excluded. In both of these sessions select committees were appointed to look into the matter across the Transkei and report back: in both instances the committees referred to the 'well known' fact 'that there were some forests where very large tracts of grass lands had been included in demarcated areas without any use whatever being made by the Forest Department of these tracts.'73Throughout the following decade, similar frustrations with state restrictions on available and unused forest pasturage amid commonage grazing pressures led to perpetual attempts by headmen and prominent stockowners to alter the Forest Department's livestock and land management policies in their locations, albeit to little avail.74 The government's system of forest demarcation and reservation, originating in the formative years of colonial takeover, continued to precipitate grazing conflicts amid this era of mounting rural stress.

Conclusion

Such long-term consequences of colonial environmental policies suggest a rethinking of the history of people and their landscapes in the Eastern Cape. While men and women in the region would begin to feel the impact of state betterment interventions from the mid-twentieth century onward, the focus of much of the literature,75 people across the Transkei had already been involved in multiple contestations over the state's restructuring of their environmental base and livelihood practices during the formative decades of colonial rule. Even when scholars have explored environmental dimensions of livestock management for earlier years, they have generally limited their discussion to data on land and livestock holding within the confines of African locations.76 Taken together, such studies convey a somewhat limited conceptualisation of historical landscapes, one which tends to reflect state demarcations and definitions of resources - segregating African locations and state-owned forest reserves - more than those of African historical actors themselves.77

As this article has demonstrated, from the 1890s to the 1930s colonial authorities strove to exclude rural livelihood practices from government forests, yet local residents were not satisfied with the removal of forest lands and resources from their resource base. Although the state demarcated certain areas as reserves, local resource-users contested such categories in day-to-day practice, continuing to depasture their livestock in government forests, publicly protesting state interventions into their lives and livelihoods, and directly calling into question the nature of state-controlled landscapes. Examining these formative colonial struggles can thus shed light on the long-term and ongoing development of resource conflicts in the Eastern Cape, particularly the complex and diverse ways in which people have historically understood both the meaning of local environments and official strategies to manage and 'develop' them.

1 Many thanks to Lwandlekazi de Klerk, Tandi Somana, and Veliswa Tshabalala for assistance in interviewing and translation and to Leslie Bank, Andrew Bank, and the anonymous reviewer for their editorial insights and suggestions. This research was supported by grants from the Joint Committee on African Studies of the Social Science Research Council and the American Council of Learned Societies, with funds provided by the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Graduate School of the University of Minnesota.

2 For example, C. de Wet, Moving Together, Drifting Apart: Betterment Planning and Villagisation in a South African Homeland (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1995); W. Beinart, 'Transkeian Smallholders and Agrarian Reform', Journal of Contemporary African Studies, vol. 11(2), 1992, 178-99; F. Hendricks, 'The Pillars of Apartheid: Land Tenure, Rural Planning and the Chieftaincy' (Ph.D. thesis, Uppsala University, 1990); idem, 'Loose Planning and Rapid Resettlement: The Politics of Conservation and Control in Transkei, South Africa, 1950-1970', Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 15(2), Jan. 1989, 306-25; P.A. McAllister, 'Resistance to "Betterment" in the Transkei: A Case Study from Willowvale District', Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 15(2), Jan. 1989, 346-68; T. Moll, No Blade of Grass: Rural Production and State Intervention in Transkei, 1925-1960 (Occasional Papers 6, Cambridge University, African Studies Centre, 1988); W. Beinart and C. Bundy, Hidden Struggles in Rural South Africa: Politics and Popular Movements in the Transkei and Eastern Cape, 1890-1930 (London: James Currey, 1987), 191-221; W. Beinart, The Political Economy of Pondoland, 1860-1930 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 70-84, 104-9.

3 I explore this contested histoiy at length in 'Roots and Rights in the Transkei: Colonialism, Natural Resources, and Social Change, 1880-1940' (Ph.D. thesis, University of Minnesota, June 2002).

4 Annual Report of the Conservator of Forests, Transkeian Territories 1893, 136. (For the remainder of the article, I will refer to all annual reports of the Forest Department simply as Annual Report followed by the year concerned.) For some typical official remarks of this period condemning the forest destruction caused by African livestock 'trespass', see Cape Town Archives (CTA), CTA Archives of the Conservator of Forests, Transkeian Conservancy (FCT) 2/1/1/1, FCT to Chief Magistrate of the Transkei, 7 August 1890; CTA Archives of the Chief Magistrate of the Transkeian Territories (CMT) 3/40, FCT to CMT, 1 August 1893; ibid., 2 August 1893, FCT to CMT; Cape of Good Hope, G.62-1893, Report on the Extent, Value, and Administration of the Forests of the Transkei and Griqualand East (1893); CTA Archives of the Secretary for Native Affairs (NA) 321, CMT to Under-secretary for Native Affairs (USNA), 4 August 1893; Annual Report 1893, 139-40; C.C. Henkel, Tree Planting for Ornamental and Economic Purposes in the Transkeian Territories, South Africa (Cape Town: Juta, 1894), 39, and 'Supplement', 4; CTA CMT 3/40, FCT to CMT, 20 November 1895.

5 The following description synthesises multiple sources: E. Pooley, The Complete Field Guide to the Trees of Natal, Zululand and Transkei (Pietermaritzburg: Natal Flora Trust Publications, 1993); K.H. Cooper and W. Swart, Transkei Forest Survey (Durban: Wildlife Society of Southern Africa, 1991); S. Cawe, 'Coastal Forest Survey: A Classification of the Coastal Forests of Transkei and an Assessment of their Timber Potential' (Umtata: University of Transkei, 1990) and 'A Quantitative and Qualitative Survey of the Inland Forests of Transkei' (M.Sc. thesis, Department of Botany, University of Transkei, Jan. 1986); J.M. Feeley, 'The Early Farmers of Transkei, Southern Africa before A.D. 1870', Cambridge Monographs in African Archaeology 24, Bar International Series 378 (1987); W. D. Hammond-Tooke, Command or Consensus: The Development of Transkeian Local Government (Cape Town: David Philip, 1975), chapter 1; H.C. Schunke, 'The Transkeian Territories: Their Physical Geography and Ethnology', Transactions of the South African Philosophical Society, vol. 8, Part I (1893), 1-15.

6 These fall into the category of mist belt mixed Podocarpus forests.

7 Mangrove communities and swamp forests exist in the northernmost areas of the coastal forests, for instance. Deep gorges also interrupt some major forest blocks in this region as rivers wind their way to the sea.

8 For the purposes of this article, I am limiting my discussion to the meaning of landscapes for livestock management. For deeper analysis of varied local perspectives on the value of grassland and forest environments in the Transkei's past, see my 'Roots and Rights', especially chapters 4 and 7; T. Kepe and I. Scoones, 'Creating Grasslands: Social Institutions and Environmental Change in Mkambati Area, South Africa', Human Ecology, vol. 27(1), 1999, 29-53; T. Kepe, Environmental Entitlements in Mkambati: Livelihoods, Social Institutions and Environmental Change on the Wild Coast of the Eastern Cape, Research Report No. 1 (Bellville: PLAAS, School of Government, University of the Western Cape, 1997).

9 Proceedings and Reports of Select Committees at the Session of the Pondoland General Council (PGC), 1914, 27-8, Councillor Jiyajiya.

10 S. Milton and C. Bond, 'Thorn Trees and the Quality of Life in Msinga', Social Dynamics, vol. 12(2), Dec. 1986, 64-76.

11 CTA NA 321, CMT to USNA, 4 August 1893.

12 CTA CMT 3/87, Resident Magistrate (RM) Engcobo to CMT, 24 June 1895; CTA FCT 3/1/51, T700, District Forest Officer, Umtata (FDU) to FCT, 21 November 1927; Annual Report 1927, 6; Annual Report 1932, 75, Eastern Cape Inspectorate.

13 CTA Records of the Resident Magistrate of the Tsolo District (1/TSO) A1/1, Minutes, Chairman of the Tsolo District Council, statement of W. Mehlo, 27 November 1908; see also CTA CMT 3/648, 91/8/1, RM Kentani Frank Brownlee to CMT, 25 November 1912, explaining the concerns of one headmen and his location - that if local forests were reserved, 'their cattle would be unable to obtain necessary shelter in cold weather'; and CTA Records of the Resident Magistrate of the Lusikisiki District (1/LSK), 6/1, Journal, 'Meeting with Marelane's Deputation', 23 September 1914.

14 For example, CTA Records of the Resident Magistrate of the Kentani District (1/KNT), 5/1/1/19, RM Kentani to CMT, 30 January 1907; Proceedings and Reports of Select Committees at the Session of the Transkeian Territories General Council (TTGC), 1912, 23, statement of councillor Lavisa, Butterworth district; CTA CMT 3/648, 91/8/1, Newton O. Thompson, Kentani, to Acting RM Kentani Frank Brownlee, 18 September 1912; TTGC 1926, 100, 'Access of Cattle to Water in Demarcated Forests'; National Archives Repository (NAR), Pretoria, Archives of the Native Affairs Department (NTS) 6947, 110/321, RM Kentani to CMT, 23 March 1929.

15 Interviews with Adolphus Qupa, Baziya Mission Station, Umtata district, 8 January 1998; Anderson Joyi, Mputi, Umtata district, 23 December 1997; Mvulayehlobo Jumba and Charlie Banti, Tabase, Umtata district, 27 January 1998; Dabulamanzi Gcanga, Manzana, Engcobo district, 5 February 1998.

16 CTA FCT 3/1/56, T115, Butterworth Division, District Forest Officer (DFO) Butterworth to Asst. FCT, 14 May 1908. This situation may in fact have reflected various cattle-loaning and borrowing arrangements at work across the Transkei. See, for example, M. Hunter, Reaction to Conquest: Effects of Contacts with Europeans on the Pondo of South Africa (London: Oxford University Press, 1936), 136-9; Beinart, Political Economy of Pondoland, 14-17, 79-80, 83; Hendricks, 'Pillars of Apartheid', 100; E. Wagenaar, 'A History of the Thembu and their relationship with the Cape, 1850-1900' (Ph. D. thesis, Rhodes University, 1988), 345-6; Kepe, Environmental Entitlements in Mkambati, 70. For other comments by officials and Africans themselves regarding forests' significance during dry seasons and droughts, see CTA CMT 3/40, FCT to CMT, 20 November 1895; Annual Report 1895, 171; CTA NA 702, B2850, RM Libode to Asst. CMT, 24 October 1904; ibid., Asst. CMT to SNA, 27 October 1904; Annual Report 1904, 137; CTA FCT 3/1/7, F110/10, RM Arthur Gladwin, Lusikisiki, to CMT, 24 September 1914; PGC 1914, 27-28, statement of councillor Dywili; CTA Archives of the DFO Kokstad (FKS) 4/1/1, 'Foresters' Reports 1926-27', Lusikisiki district; TTGC 1926, 100, statement of Albert Ludidi, Qumbu district; Annual Report 1927, 6; Annual Report 1932, 75; Annual Report 1934, 13.

17 Interview with Nozolile Kholwane, Fairfield, Umtata district, 23 February 1998.

18 Interview with Mvulayehlobo Jumba and Charlie Banti.

19 Interview with William Jumba, Tsikitsiki Nodwayi, Festo Sonyoka, and Zwelivumile Quvile, Tabase, Umtata district, 4 February 1998.

20 Ibid.

21 This holds particularly true for interviewees currently living in several peri-urban locations outside Umtata, following their often traumatic experiences of apartheid betterment and resettlement planning in the late 1950s and 1960s. See J. Tropp, 'Displaced People, Replaced Narratives: Forest Conflicts and Historical Perspectives in the Tsolo District, Transkei', Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 29(1), Mar. 2003, 207-33.

22 CTA CMT 1/31, statement of Headman Tafa before RM Engcobo, 4 November 1889, enclosed in RM Engcobo to CM Tembuland, 28 November 1889.

23 Imvo Zabantsundu's criticism of forest grazing restrictions on location commonages in 1893 responded directly to such practices and the 'excessive zeal of some fussy officials, dressed in little brief authority, in the Forest Department recently inaugurated'. Imvo, 20 September 1893, 'Commonage Rights', 3.

24 Proclamation 209 of 1890, section 10.

25 CTA NA 321, CMT to USNA, 4 August 1893; see CTA CMT 3/87, RM Engcobo to CMT, 24 June 1895, for some similar comments.

26 Proclamation 387 of 1893; CTA NA 321, CMT to USA, 16 November 1893; Proclamation 402 of 1894; Proclamation 408 of 1896; CTA CMT 3/94, Asst. CMT to FCT, 18 July 1905; NAR NTS 6947, 110/321, Chief Conservator of Forests (CCF) to Secretary for Native Affairs (SNA), 21 February 1929.

27 For instance, Proclamation 388 of 1896, section 8, empowering magistrates to restrict depasturing in location forests within their districts, seems to have had little impact given its inadequate enforcement.

28 For example, CTA FCT 2/1/1/1, FCT to CM Transkei, 7 August 1890; Annual Report 1893, 136; CTA CMT 3/40, FCT to CMT, 1 August 1893; Henkel, Tree Planting, 39, and 'Supplement', 4; CTA CMT 3/40, FCT to CMT, 20 November 1895; Annual Report 1895, 171; Annual Report 1896, 155-56; CTA FCT 2/1/1/2, FCT to USA, 14 September 1896.

29 Annual Report 1899, 96; Annual Report 1904, 137; Annual Report 1904, 137; Annual Report 1911, 10; NAR FOR 225, A365/27, SNA to CCF, 18 March 1912; CTA FCT 3/1/49, T511/1, CMT to SNA, 2 July 1915; CTA FCT 3/1/51, T700, FDU to FCT 21 November 1927; NAR NTS 6947, 110/321, CCF to SNA, 21 February 1929; TTGC 1929, 'Report of Select Committee on Land Matters', 46, Item no. 57, Fencing of demarcated forests; Annual Report 1932, 82-3; CTA CMT 3/1319, 24/4, CCF to Chief Clerk, 1 November 1933; TTGC 1934, 221; Annual Report 1937, 11; Annual Report 1938, 8.

30 Proclamation 135 of 1903, sections 10, 17, 25b, and 42-47.

31 The annual report for 1906, for example, offered the following totals of stock impounded after caught trespassing in government forests during the year: six horses, 117 cattle, 268 sheep, and 1,114 goats. Two years later some 1,391 animals were impounded for similar offences. Annual Report 1906, 13; Annual Report 1908, 11.

32 CTA Archives of the Secretary for Agriculture (AGR) 144, 595, part 1, FCT to Under-secretary for Agriculture (USA), 14 May 1894; CTA FCT 2/1/1/2, FCT to USA, 15 September 1896; ibid., FCT to USA, 3 November 1896; CTA CMT 3/131, RM Mt. Frere to Chief Magistrate of East Griqualand (CMK), 21 March 1902.

33 Ibid., original emphasis; FCT to CMT, 13 October 1902; RM Mt. Frere to CMT, 17 October 1902; RM Mt. Frere to CMT, 6 November 1902.

34 CTA FCT 3/1/56, T115, Butterworth Division, Divisional Engineer of Public Works, King William's Town, to Asst. FCT, 7 April 1908. For local conflicts over forest grazing in the area, see ibid., DFO Butterworth to Asst. FCT, 14 May 1908; ibid., DFO Butterworth to Asst. FCT, 6 August 1908; TTGC 1908, xxviii-ix, comments of Enoch Mamba, Idutywa district; NAR Archives of the Department of Forestry (FOR) 276, A550, 9/17/09, Asst. FCT to CCF, 17 September 1909; ibid., Asst. FCT to CCF, 23 September 1908; CTA NA 753, F127, CCF to SNA, 7 October 1909. Some European farmers in a neighbouring district also complained about their livestock being impounded for trespass when the forest reserves were not properly fenced in: NAR FOR 276, A550, translation of Afrikaans letter from O.J. Oliver, N.J. Kockemoer, J.H. de Bruyn, Noah's Ark, Elliot, to Surveyor-General, 7 July 1909.

35 This restriction, already applied to goats since 1903 (Proclamation 135, sections 10, 17, and 47), was implemented for all livestock in demarcated forests on a temporary and ad hoc basis in the late 1900s. See CTA AGR 739, F1930, FCT to USA, 6 July 1904, and GN 1183 of 1909, regarding the closing of certain St. Mark's and Engcobo district forests to grazing respectively.

36 Government Notice (GN) 668 of 1911.

37 NAR FOR 225, A365/27, SNA to CCF, 18 March 1912, forwarding extracts from 'Notes of a meeting of Chief Marelane and Pondos with the Chief Magistrate at Umtata, 7th Sept. 1911'.

38 TTGC 1912, 22-3, Trespass of Cattle in Forests', 2 May 1912; NAR NTS 6947, 110/321, CMT to SNA, 8 June 1912. Popular resentment towards official livestock policies were generally intensifying at this time, in response to newly imposed dipping and cattle disease regulations. (Beinart and Bundy, Hidden Struggles, 191-221).

39 Ibid.; TTGC 1913, 17, 'Grazing of Stock near Demarcated Forests'. In a typically condescending official response to African criticism of forest regulations, CMT Arthur Stanford publicly rebuked leaders at the 1912 TTGC session: 'It must be patent to anybody with any intelligence that young growth would be very seriously retarded by the grazing of stock in these forests, and if there was no re-growth of sapplings [sic] the forests would in time disappear altogether. ' TTGC 1912, 23, 2 May 1912. The basic premise of GN 668 was repeated and expanded in GN 1605 of 1920, section 4 and GN 987 of 1935.

40 In 1921, for example, local leaders of the All Saint's Mission location in the Engcobo district petitioned their magistrate to have the Bulembu forest completely fenced 'and thereby save us the needless source of worry and expense. The forest is in the middle of our small grazing area and has been part of it before it was taken over by Government. In spite of all our efforts to keep away our herds and flocks they will trespass and consequently we have to pay very frequently. ' CTA CMT 3/1325, 24/4/2, Part I, Kilili Poswayo, Hen Ntshnga, Sam Gasa, and Charles Hlati, All Saints Mission, to RM Engcobo, 22 January 1921, original emphasis; see also CTA FCT 3/1/7, F110/10, RM Lusikisiki to CMT, 24 September 1914.

41 The table draws from data in Annual Report 1901, Annexure A, 165-7.

42 Annual Report 1901, 165-7; Annual Report 1904, 136.

43 Annual Report 1906, 18-19.

44 CTA CMT 3/1319, 24, Part V, 'Forest Demarcations: Transkeian Conservancy, 1936', FCT to CMT, 20 February 1936; Annual Report 1937, 56.

45 CTA CMT 3/785, 406, confidential letter, CMT to RM Bizana, 12 May 1908. Stanford refers to the Forest Department's occasional practice in these early years of temporarily leasing out grazing lands in forest areas to European stockowners in the Territories. Similar comments are made in Report of the Select Committee on Crown Forests (1906), 1-3, CCF Lister; NAR NTS 6937, 50/321, CMT Arthur Stanford to USNA, 19 September 1910.

46 Imvo, 20 November 1906.

47 CTA CMT 3/131, RM Mt. Frere, to CMK, 21 March 1902, original emphasis. See also a complaint by one African writer to Imvo in 1900, complaining about government plantations in the Transkei and how they 'lessen grazing ground, so much that stock of every kind are being constantly taken to the pound for trespassing on these plantations. Natives live by rearing moveable property, and if things go on in this way they must suffer. ' Imvo, 17 November 1900, letter to editor by Tanduhlanga.

48 D. Moore, 'Contesting Terrain in Zimbabwe's Eastern Highlands: Political Ecology, Ethnography, and Peasant Resource Struggles', Economic Geography, vol. 69, 1993, 380-401, especially 392-3. [ Links ]

49 Forest Officer Knut Carlson later reflected on how Africans consistently objected to ground being appropriated for grazing lands in these years: K. Carlson, Transplanted: Being the Adventures of a Pioneer Forester in South Africa (Pretoria: Minerva Drukpers, 1947), 128.

50 CTA NA 753, F127, RM Cofimvaba to CMT, 14 December 1908; CMT to SNA, 24 December 1908.

51 PGC 1914, 27-28.

52 NAR NTS 6937, 50/321, CMT to USNA, 19 September 1910.

53 Annual Report 1913, 8; TTGC 1926, viii-ix, minute no. 83, Report of Select Committee on Land Matters, Section 5, Reversion of Land between Forest Beacons to Commonage, in which the CCF refers to his comments on the matter back in 1915; PGC 1916, 23-4, referring to the CCF's opinion 'that many forests were very irregular in shape and if a beacon were put at every corner, the cost would be very great, and the Forest Department only marked the ground roughly.'

54 Ibid., 23-4, 57, 59. Mpondo chiefs aggressively defended popular access to scarce grazing lands from state intervention in these years: Beinart, Political Economy of Pondoland, 122-3. For broader complaints at this time, see TTGC 1916, 57, 59; CTA CMT 3/827, 561, RM Tsolo to CMT, 5 January 1916, enclosing minutes from the district council meeting of 24 November 1915. In the early 1920s, conflicts over productive farming lands in certain forest reserves in the Elliotdale district similarly revolved around the scale of 'unused' land marked off by demarcation beacons. In explaining local residents' complaints, the resident magistrate informed the CMT that many of the beacons stood some 200 yards 'and in many cases a good deal farther, from the forest. The Forest Department, apparently, have no intention of making use of this ground themselves.' CTA CMT 3/1319, 109E, RM Elliotdale Harland S. Bell to FCT, letters of 19 and 22 October 1923.

55 Beinart, Political Economy of Pondoland, 77-83; idem, Transkeian Smallholders', 178-79, 182; Moll, No Blade of Grass, 9-10; Kepe, Environmental Entitlements in Mkambati, 16-17; C. Simkins, 'Agricultural Production in the African Reserves of South Africa, 1918-1969', Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 7(2), 1981, 256-83, particularly 260; A. Charman, Progressive Élite in Bunga Politics: African Farmers in the Transkeian Territories, 1903-1948' (Ph.D. thesis, Cambridge University, 1999), 229.

56 Beinart, Political Economy of Pondoland, 82, describes how during this period sweetveld areas in several Pondoland districts were gradually replaced by sourveld grasses, which became inedible in certain seasons; idem, Transkeian Smallholders', 179; Moll, No Blade of Grass, 9, 11-12; R. Southall, South Africa's Transkei: The Political Economy of an 'Independent'Bantustan (New York, 1983), 74, 80-81.

57 Ibid., 85-86; Moll, No Blade of Grass, 16; on the problematic nature of statistics on livestock distribution, see Beinart, Transkeian Smallholders', 180-83; Hendricks, 'Pillars of Apartheid', 100-1.

58 TTGC 1926, 100, 'Access of Cattle to Water in Demarcated Forests', councillor Albert Ludidi.

59 Interview with Dabulamanzi Gcanga.

60 Annual Report 1895, 171; CTA AGR 739, F1930, William Mdleleni, Cofimvaba, to Secretary for Agriculture, 14 June 1904; Imvo, 20 November 1906.

61 For example, TTGC 1925, Report on Plantations, xvii; CTA FCT 3/1/51, T700, FDU to FCT, 21 November 1927; NAR NTS 6947, 110/321, CCF to SNA, 21 February 1929; CTA CMT 3/1319, 24/1, FDU to CMT, 4 May 1936. Removing fencing wire could also serve other purposes besides livestock access and protest: over the years, officials recorded that in different locales 'natives cut the wire to let their stock in and also remove it for repairs to their sledges and ploughs, etc.' or also to craft jewelry. NAR NTS 6947, 110/321, CCF to SNA, 21 February 1929; Annual Report 1895, 171.

62 Interview with Polisile Maka, Manzana, Engcobo district, 28 January 1998.

63 Interviews with Tozama Gqweta, Baziya Mission, Umtata district, 12 January 1998; Headman Sithelo, Kaplan, Umtata district, 25 February 1998; William Jumba et al.

64 This was part of a broader political alliance of a 'progressive elite' in the Bunga to advance and protect their class interests as farmers. Charman, 'Progress Elite'.

65 TTGC 1929, 144-45, statements of S.S. Matoti, Josiah Xakekile, and S. Sopela, and see also that of RM Butterworth Frank Brownlee, 144.

66 TTGC 1925, 78-9, 175; TTGC 1930, xiv; UTTGC 1933, 66; Annual Report 1934, 15; UTTGC 1934, 65; CTA FCT 3/1/24, T102/5, George Gcanga, Charles Xundu, Vacuza Tshila, John Buka, and Joe Plata, petition before Native Commissioner, Engcobo, 8 October 1935; Annual Report 1937, 11,16, 20; Annual Report 1938, 22-23; UTTGC 1940, 55, 199; Interviews with Tozama Gqweta; Polisile Maka.

67 Moll, No Blade of Grass; W. Beinart, 'Soil Erosion, Conservationism and Ideas about Development: A Southern African Exploration, 1900-1960', Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 11(1), Oct. 1984, 52-83; Hendricks, 'Pillars of Apartheid'.

68 PGC 1918, 14, Councillor S. Gwadiso, Ngqeleni; CTA CMT 3/1329, 24/14/2, DFO Mt. Frere to FCT, 3 May 1923; ibid., RM Mt. Frere to CMT, 11 June 1923; TTGC 1928, 59-60; CTA CMT 3/1325, 24/4/2, Part I, Forest Reserves Engcobo, 'A Stock Owner', Emjanyana, to CMT, 15 July 1932; Union of South Africa, U.G.22-1932, Report of the Native Economic Commission, 1930-32 (NEC), vol. 6, 3344, Fred Roland Blythe Thompson, Principal of Teko Agricultural School; ibid., 3786-88, John Guma and Nantiso Kula.

69 Some of these different factors are reflected in a debate on the subject in TTGC 1928, 59-60.

70 CTA CMT 3/1325, 24/4/2, Part I, Forest Reserves Engcobo, 'A Stock Owner', Emjanyana, to CMT, 15 July 1932.

71 For more on the political and economic perspectives of this 'progressive' class of men during this period, see Charman, 'Progressive Élite'.

72 TTGC 1925, 78-9, Councillors Matsolo Mgudlwa and S.S. Matoti, St. Mark's district, and Tyuluba, Xalanga district.

73 Ibid., 175, RM Umtata J. Mould Young; TTGC 1929, 6, and 45-6, 'Report of Select Committee on Land Matters'.

74 TTGC 1930, 46; TTGC 1931, 68; NEC, vol. 5, 3016-17, Benjamin Siposo Ncabene, Port St. John's; Proceedings and Reports of Select Committees at the Session of the United Transkeian Territories General Council (UTTGC) 1933, 66; UTTGC 1934, 65, 221-23; CTA FCT 3/1/24, T102/5, George Gcanga, Charles Xundu, Vacuza Tshila, John Buka, and Joe Plata, petition before Native Commissioner, Engcobo, 8 October 1935; UTTGC 1938, 75; UTTGC 1940, 55, 199.

75 For example, de Wet, Moving Together, Drifting Apart; Hendricks, 'Pillars of Apartheid' and 'Loose Planning and Rapid Resettlement'; McAllister, 'Resistance to "Betterment"'.

76 Beinart, 'Transkeian Smallholders'; idem, Political Economy of Pondoland, 70-84; Moll, No Blade of Grass.

77 For some recent insightful approaches to reconceptualising landscape categories through local historical perspectives, see T. Giles-Vernick, Cutting the Vines of the Past: Environmental Histories of the Central African Rain Forest (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 2002); H. Gengenbach, '"I'll Bury You in the Border!": Women's Land Struggles in Post-War Facazisse (Magude District), Mozambique', Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 24(1), March 1998, 7-36.