Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.30 no.1 Cape Town 2004

Framing African women: visionaries in southern Africa and their photographic afterlife, 1850 - 2004

Helen Bradford

University of Cape Town

How would you describe this?

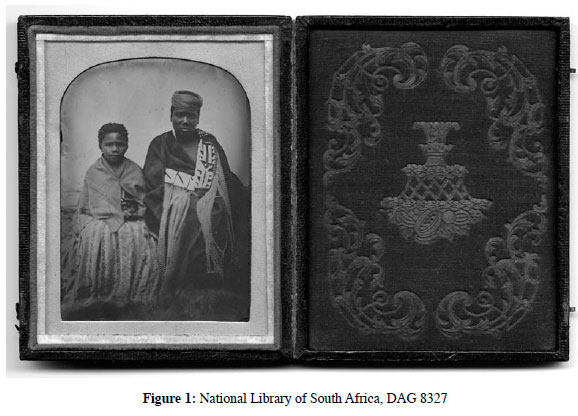

Look closer - at the frame. The photograph is an illusion. Frames, advertised as 'Fancy Cases', operated like kaleidoscopes.1 This Fancy Case is not adequately represented here. Immediately surrounding the optical illusion (the monochrome photograph) is curved brassy metal. It shrieks for attention. Maroon velvet, embossed with pinkish curlicues, covers the opposite side. Two velvet strips, maroon and white, surround the yellow metal on the photographic side. The eye tends to flinch away from this frame, away from an image rendered drab by its surrounds, towards the marginally more restful maroon. Everything is enclosed in a papier mâché case, with moulded floral patterns on the reverse side.

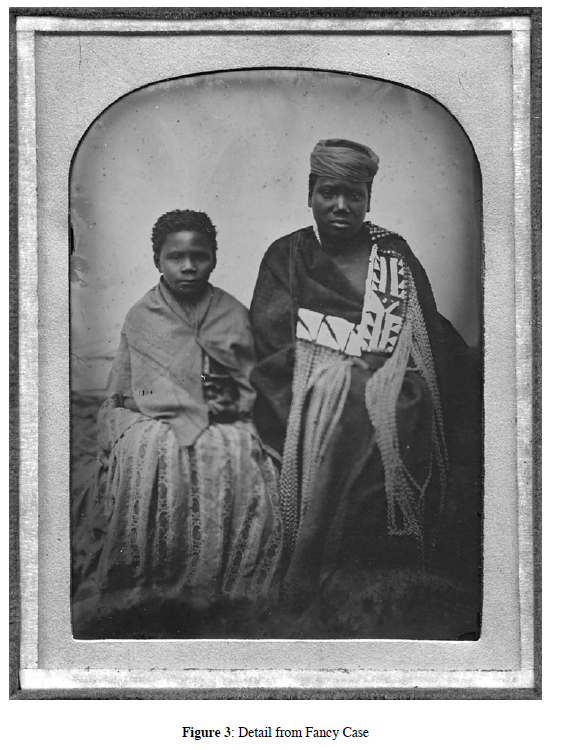

An optical illusion in a Fancy Case looks different, then, from its representation on a monochrome page. This photograph also looks different from others in similar frames. Normally, the case would open like a book; the image would be on the right. Western literate eyes, accustomed to travelling from left to right, would move from decorative fabric to the illusion. This reversed order is disturbing: like a book titled on its back cover. The urn in the centre of the velvet also causes unease. It is - inverted. If an urn has connotations of death, what does a pink inverted urn denote? On the reverse side, the bunches of flowers are also upside-down. If the Fancy Case were to be displayed as normally as possible, then it would be depicted like this.

Frames, clearly, structure how we see and think about what they enclose. If this one is upright, then a pinkish metropolitan symbol of fertility becomes the focal point. Inverted people are troublesome, but the monochrome image is marginalized. Nonetheless, despite its significance, this frame is invariably cropped when the photograph is reproduced. Never are we visually informed that African women were surrounded by a Victorian frame, which created them. Never is it suggested that they were, perhaps, intended to be presented upside-down: of a piece with all other signs of an alien frame overwhelming a captive image.

When I first handled this Fancy Case, it changed my appraisal of ifoto. I saw not two large upright people on a page, lent credibility and respectability by a close-up, neutral colours, a modern moulding (a white paper border) and a broader frame (an academic book), but decentred distant dwarves, surrounded by garish metal, glass, velvet and papier mâché. They jarred with the Fancy Case whichever way I looked at them. Stripped of the truth-effects injected by modern frames, ifoto was but one more product of an industrializing Victorian empire - and an optical illusion at that. Since this reflected the circumstances in which it was created, the Fancy Case was more evocative than modern replacements. Like all photographs, the original ripped its subjects out of history, freezing them in contingent identities; modern frames further legitimated their unnatural appearances; the Fancy Case historicized them, returning them to an overpowering world of imported metal, maroon and frame-ups. What follows continues this process of placing visual illusions back within the bigger picture (particularly contexts which have been marginalized). The poor visibility of these broader frames, I suggest - together with their replacement by modern ones - means that our own visions have been impaired.

Genesis of a Frame-up

In 1858, in King William's Town, a British colonial capital, a camera framed two people born in Xhosaland. Behind it stood a white man calling himself a photographic artist. He was an itinerant jack-of-all-trades, having just added the newfangled camera to his dubious repertoire. This embraced conjuring, alleged forgery, bilking, turning a bottle store into a hotel - and levelling his lens at black women's breasts. He would blazon his name, 'DURNEY', near their flesh.2

His were not unusual practices for a colonial photographer in British Kaffraria and its adjacent zones. White men virtually monopolized the camera, but struggled to make a living. In an era when display of a white woman's ankle was deemed erotic, they were just discovering that colonized women could be posed in more lucrative ways. But Michael Durney's visions of black women seem darker than the norm; they were inflected by his history as a mountebank. Among his surviving prints is one which combined different negatives (as is not apparent to a casual viewer). Large sagging breasts are its focal point. The woman to whom they belong, smoking a pipe, has acquired at her feet another image: a crouching girl. What resembles a foetus lies on the ground. Breasts, pipe, foetal imagery, odd doings between a semi-naked woman and a clothed child, a photographic fiction: this print is banned for republication today, without special permission. Another Durney print depicts two grim bare-breasted women, their arms and hands so positioned and ornamented as to suggest handcuffs. They are accorded, alongside signifiers of racial identity, photographically whitened skins. Durney's surviving images of black female pairs possess an atmosphere of the sexualized grotesque.3

What was this female pair doing in the studio of such a man? A Superintendent of Native Hospitals had ordered them there. A British officer's wife 'dressed them up for me & I had them Photographed by Durney.'4 They had been escorted to a hotel room, and posed. A cheap negative was generated, consisting of an emulsion on a small piece of glass. This was sandwiched into an equally cheap presentation case, over an opaque backing (commonly black paper, black cloth or smoked glass). The negative now reflected light. Its light portions looked dark. Its dark portions - composed of silver grains - looked light. A negative had been turned into a positive. Two dark people almost miraculously appeared, in a Fancy Case, which could be snapped shut and put in a pocket, whereupon they would disappear. A conjurer then sold this package to the Superintendent. He, an amateur historian, intended to use it and other photographs in an illustrated history, demonstrating the evils of the cause which these two people had promoted.

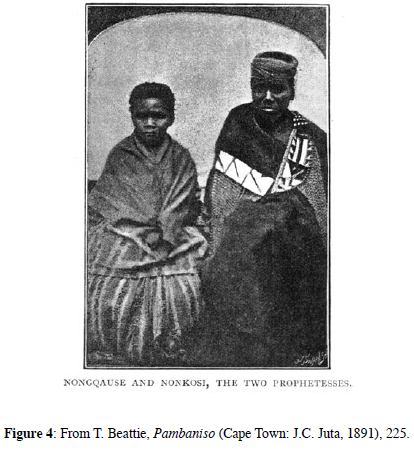

The photograph, then, encoded the desires, visions and technologies of invisible settlers. Its ostensible subjects were bit players: only the barest traces of their histories are imprinted on a stage-managed illusion in a Fancy Case. Just visible as it protrudes beneath a sleeve, then extends into a bent cylinder registering its presence only through a shadow, is the painfully thin arm of the intombazana (little girl). Eleven months earlier, Nonkosi had been at her home in British Kaffraria, near East London. There had been little to eat, for months. Her chiefdom was deadly still; animals, crops, people, had evaporated. The head of her homestead, her uncle, had fled, with his immediate family. Her mother had died. Three dead children and one woman lay unburied in her homestead. Her father, a priest/healer, was almost moribund. Then black policemen arrived. They arrested Nonkosi. They killed her father. They escorted her to detention. The military officer ruling British Kaffraria immediately decided her fate. She would be jailed, several hundred miles away, in another British colony. A 'suicidal tendency was at one time much kept down by ... the stake through the body,' noted the colonel. Similarly, if she were pinioned in jail, 'mad prophets & ... nervous females' would eschew her path.5 She was about eleven years old. She had just left behind her five unburied people, including her father. She had not been charged, let alone tried.

The intombi (maiden) beside her, Nongqawuse, said to be about eighteen, had similar experiences: starvation, death of kin, flight, pursuit by armed men, capture, detention, interrogation. Both of them, three months after this photograph, were sent to the 'Female Kaffer Prison' in Cape Town, capital of the Cape Colony.6

The Fancy Case, with its captive optical illusion, symbolizes the immediate circumstances in which a colonial vision was created. But without a longer history - and without rendering visible what is typically invisible - we still cannot place it in perspective.

Armageddon in Red and Black

In 1847, around the time of Nonkosi's birth, her country was dead (at war). At the end of this seventh frontier war, methods of ruling this blood-stained region changed. A new British Governor strode across southern Africa, as the alleged father of indigenous people. On maps, a tidal wave of red followed him. He approximately doubled the area under British rule, dismembering Xhosaland in the process, turning half of it and part of Thembuland into the new colony of British Kaffraria. In the older Cape Colony, many British immigrants were 'delirious with joy ... Millennium!'7 In the midst of a wool boom, they flocked into annexed territories. Alternatively, they added unutilized farms to their speculative portfolios. Land loss, throughout the newly colonized region, was the most acute grievance. 'You are civilized', said the ruler of annexed LeSotho to a missionary. 'You do not steal cattle, it is true: but you steal entire countries. And if you could, you would send our cattle to pasture in the clouds.'8

This earthquake occurred in a natural world that was running amok. Between Nongqawuse's birth and adolescence, when that part of dismembered Xhosaland where she lived was one of the few remaining pockets of independence, serial catastrophes hit the Cape and its frontier zones. Smallpox was followed by a horse epizootic. Then came highly contagious imofu: a 'fatherland' bull. (A metropolitan bull had transported a cattle epidemic across the Atlantic.) Almost all diseases, disasters and deaths, declared priest/healers, were caused by occult animals or substances, wielded by malevolent people. They were clearly omnipotent: to a fatherland bull were added a flood, an earthquake, two droughts, two severe famines, almost perpetual war. Cattle, pivotal in diets, were being decimated. In 1848, in colonized Xhosaland, where patriarchs virtually monopolized stock, one in three adult men surveyed possessed no cattle. Eighty per cent owned five or fewer.9

The classic context for millenarianism existed: natural and social cataclysms; societal decomposition at an accelerated pace. Millenarian movements (which have erupted worldwide and continue to do so today, not least in the United States) reject a nightmare world. They direct eyes towards a future millennium. Tactics have ranged from preparation for divine intervention, to exceptionally bloody assaults on the old order, inspired by what is central to the millenarian dream: the absence of everything defined as imperfect or evil, including evil people, evil weapons.

From 1850, such a movement engulfed southern African regions newly incorporated into a harsher colonial order, or threatened with this fate. Mobilizing many more people than any subsequent South African movement, for over a century, it unified multi-ethnic followers under three banners: blackness; return of a golden precolonial age; eradication of evil. Leadership derived not from patriarchal politicians in precipitous decline, but from healing/spiritual specialists, consulted across ethnic divides and female-dominated. Most were amagogo: seers surveying distant reaches of space and time, sharing their name with mountain buck. Some two dozen emerged, often influenced by Africanized Christianity. They were typically socially distant from a patriarchal elite; they tended to appeal most to those similarly placed.10 The movement they inspired ebbed and flowed, lasting between two and eight years, depending on region. What remained constant were crises in peasant livelihoods and patriarchal authority; war panics as catalysts for upsurges; longings for new patriarchal patrons; and willingness to die rather than live in a monstrous world.

Towering above all visionaries was the first one, a sickly healer/priest of about twenty, in colonized Xhosaland. Passionate about disease, pollution and life after death, he purified himself by virtually living in a river, acquiring the nickname Mlanjeni ('In the River'). In 1850, people consulted him about the trials of living on earth: catastrophic drought, starvation, an earthquake, impotent chiefs, life under military occupation and martial law. The Riverman promoted novel methods of eradicating the prime source of evil: ubuthi (occult materia medica).

Witchcraft, colonial authorities had announced, did not exist. When officialdom sought to jail him on Robben Island for attempting to eliminate lethal weapons, Mlanjeni was transformed into a seer. You, he informed his audience, are about to overcome the English. He had gone underwater, where he had seen Thixo and his wounded Son. Thixo was enraged by white men, who had tortured His Son. The English, and their army, and their missionaries preaching perverted gospels, and their black supporters, were all about to be destroyed by the Father, deploying cataclysmic natural weapons. This was exceptionally good news. The Riverman, it was said, was the reincarnation of a prior millenarian hero (Nxele), who had called himself Christ's brother. Chiefs were small, declared peasants, but Dr Mlanjeni kaKala radiated like the sun with the power of the Father. He possessed powers of utmost importance in a region awash with widows and orphans, ruled by impotent patriarchs subordinate to a British father. Men who were absent, it was said, again saw the sun. (Women were of no interest.) Since Mlanjeni possessed the powers of Thixo and the black brother of Christ, since he had uncovered the secret of life eternal, there would soon be 'resurrection of their ancestors, who would appear bringing their herds of old back with them, to enrich their grandsons, and rejoice with them, according to the desires of their hearts.'11

But, insisted the messiah, only the pure could enter a paradise overflowing with precolonial herds. He himself was so pure that he ate nothing touched by human hands, surviving on victuals like water grass, because people handling ubuthi defiled all they touched. Peasants had to rid homes of everything defined as filthy by an emaciated ascetic living in water. His long list, which expanded, targeted male property and practices. All cattle which were the colours of dirt or poverty (dun or yellow) were taboo, along with ubuthi, with which they were linked. Evil deeds, like bloodshed or working for the English, were also forbidden. His amulets ensured that British guns would fire no bullets - but would not protect the disobedient.

Panics that the land was about to die (almost invisible in conventional wisdom) immediately framed this entire movement. As Mlanjeni's genocidal threats exacerbated tensions, migrant labourers deserted. Starving peasants anticipated that soldiers were about to loot remaining stock, destroy grain, incinerate homes. Killing certain cattle, and eating them, had appeal. Cattleless young men would be strengthened for war. Cattleless women and children enjoyed beef. And preparations for conflict required purification, to prevent evil from weakening men, as had occurred in the long series of prior defeats. Mlanjeni's Great Cattle-Killing (1850-1) erupted, in Thembuland, LeSotho, Xhosaland, the eastern Cape.

This had a remarkable effect on settlers. It precipitated the largest evacuation of land since the Great Trek. Farmers, already crippled by desertion of their labourers, now envisaging hordes of starving looters, fled fifty, a hundred miles away from the frontier, muttering about leaving for Australia. Little could have been sweeter to black ears. Mlanjeni's cattle-killing achieved greater success than seven frontier wars: it cleared swathes of land of settlers, for over a year, without human deaths. The lessons of history became engraved on collective memory: if 'the Cattle were all ... Killed ... then the white things (English) would disappear.'12

The Riverman enjoyed similar success in other domains - but a minority of Xhosa men precipitated war. They were following culs-de-sac, the seer icily declared. He was promoting new paths; bloodshed was forbidden, except in self-defence. But an appallingly bloody war fought under genocidal slogans soon spread far beyond Xhosaland. People begged Mlanjeni to prove his power 'simply by raising one man from the dead.'13 He refused. The disobedient could not expect immortality.

Mlanjeni's millenarian war (1850-3) - the greatest war in sub-Saharan Africa in the nineteenth century - ended in devastation everywhere but LeSotho. Here he and a famous female seer had been obeyed. Stunning, almost bloodless victory over the imperial army was followed by decolonization. Xhosaland, by contrast, was in a desperate plight. Not only had impulsive warriors disobeyed Mlanjeni: the paramount chief, who remained neutral, had refused to kill his taboo cattle. Independent Xhosaland was crippled by eight invasions. Some 70,000 cattle were looted in the first incursion alone.

A vindicated Mlanjeni, settling in Nonkosi's neutral chiefdom at the war's end, renewed his popular campaign to develop tactics other than male militarism. He had spoken to fathers, he said, in a great cavern. Absent warriors would soon see the sun. He was going over the sea to meet Christ: Sifuba-sibanzi (the BroadChested One). The Riverman did indeed depart this earth - as another imperialist war exploded in Russia. His rituals were followed. Reports rang through the land: Mlanjeni 'HAS RISEN AGAIN!'14

When further hammer-blows hit reeling Xhosaland - when patriarchs welcomed being placed on British payrolls as colonial functionaries, when patriarchal cattle began dying in their myriads from the fatherland bull - commoners turned to their one source of hope. Englishmen, they noted, were being savaged, over the sea, in Russia. Mlanjeni had finally fulfilled his promises. His war was continuing. Those destroying Englishmen were great forefathers, and risen warriors. They would return, with herds untainted by the fatherland bull.

In 1855, a host of amagogo spread these tidings. Purification was urgent in environments tainted by colonialism, carcasses and prior disobedience of Mlanjeni. All patriarchs' cattle were now dirty; all had to be slaughtered. As more women became seers, as the disintegration of pastoralism placed intolerable pressure on agriculture, women's issues became prominent: cultivation should cease. The Riverman, it was known, could turn seed into crops in hours - and who cultivated when armageddon loomed? As fields were abandoned - and LeSotho flexed its muscles - the new Governor, Sir George Grey, frantically demanded more troops.

In mid-1856, as redcoats began landing, visionaries were joined by a fatherless adolescent on independent Xhosaland's coast. Mlanjeni's long-awaited black army had also landed, she announced. Risen fathers, including her own, had approached her. They said the Eternal and Broad-Chested Ones had dispatched them to destroy the English. They resided in a great cavern with stock - but refused to appear before the polluted. The 'Prophet had not yet given the word for the (Impi) Commando to go out because the people were not yet clean.'15 Patriarchs drew the line at an intombi lecturing them on hygiene. 'How can it be that our fathers come to talk about killing cattle to a mere girl,' they grumbled.16 Only when her uncle threw his masculine weight behind her, and assumed leadership, did the new oracle begin its meteoric rise. Its key innovation lay in visual politics: warriors were visible to the pure. Like women in wartime, servicing guerrillas hidden in caverns, Nongqawuse and a female relative were couriers between risen fathers and her uncle. He himself was too unclean to see them, as were almost all patriarchs. They, with their filthy hands, which had reared their bewitched cattle, were defined as prime pollutants, relentlessly spreading defilement. They reciprocated, not least by assaulting Nongqawuse.

Officialdom, fearing turmoil, and keeping a sharp eye on LeSotho, forbade obedience to the prophecies. Battalion after battalion landed. Redcoats were placed on war alert. Independent Xhosaland was threatened with invasion. A warship patrolled close to Nongqawuse's home. Consequently, repeated panics occurred: the ideal climate for impotent patriarchs to swing towards a black army. The paramount chief of amaXhosa, having learnt a bitter lesson in Mlanjeni's war, commanded destruction of cattle and forbade cultivation. Peasants ate beef, ceased cultivating, saw forefathers, called themselves 'Abanyulwa baka Thixo" ('Chosen of God').17 The recalcitrant were threatened with the punishment Mlanjeni had reserved for witches. As German mercenaries arrived, Nonkosi and her uncle began their rise to fame. She was speaking to Mlanjeni, said Nonkosi; the Broad-Chested One would soon appear. In Xhosaland and part of Thembuland, as a huge imperial army loomed over God's elect, they awaited armageddon, due on 18 February 1857. It would be inaugurated by a heavenly body closely associated with the Riverman: the sun. One word was on many lips: Mlanjeni. As was tellingly recalled,

Isanuse u Mlanjeni sawucitacita umzi. Ngo Nongqause umzi wakol-wa lilizwi le sanuse, lokuba ngomhla we 18 February 1857, kovuka abafileyo, kogxotelwe umlungu elwandle, antyiwiliselwe, kufuneka kuxelwe inkomo, kupalazwe amazimba, amasimi angalinywe.18

The sun gave no sign. Instead, as Nongqawuse and her uncle were discarded in favour of other seers, setting new dates, and as paupers attacked the propertied, Grey added, to martial law, licence to shoot to kill. Millenarianism finally began collapsing, amid barbaric repression, catastrophic famine, and ruthless eviction of the starving from thousands of square miles of land. Nonkosi was arrested in September 1857, Nongqawuse in March 1858. Eight years after they had failed to capture Mlanjeni, authorities had two of the two dozen visionaries in their hands.

A Colonial Vision

After two months in detention, and a spell in hospital, Nonkosi provided a statement that satisfied her brutal interrogators. Her uncle, she said, had asked her to help him. He and his friends had impersonated risen men, including Mlanjeni. She had been paid for telling crowds what ' Mlanjeni' had said. One of her interrogators, Major Gawler, then moved her to his home. She was to be a witness, in a show trial that he was prosecuting. As he temporarily returned to military service, savagely uprooting remaining inhabitants from independent Xhosaland, Nonkosi acquired additional duties. She joined the massively swollen ranks of female labourers, as one of Mrs Major Gawler's four black servants.19

The peasant daughter of priest/healer, standing near a river, threatening all who were associated with the English with annihilation, had now almost vanished. Nonkosi was an orphan, in a racially segregated British colonial capital, where the ideal officer's house had a separate servants' room alongside the lavatory. She was working in the home of a man whose paramilitary forces had killed her father. She was about to contribute to her chief's imprisonment on Robben Island. Further distance was placed between a child and her past, as colonial victories extended into the cultural domain. 'No Natives will henceforth be allowed to enter, or to remain in King William's Town, unless they are decently dressed in European clothing,' ran an April 1858 proclamation.20 Three months later, a photographer arrived, loudly advertising his ambrotypes (the American name for glass positives). The camera, hitherto rare in this colony and hardly ever pointed at blacks, was following in the wake of the gun. Nonkosi was dressed up under the auspices of her employer and Dr FitzGerald, who had sent her back to detention from his hospital. On a winter day, posed in a hotel room that probably stank of chemicals, before harsh lighting and a bulky machine typically inspiring fear and aversion, she was transformed into an optical illusion.

An orphan about to become a state witness was being ingested into a colonial order more rapidly than most. Mrs Major Gawler probably supplied most of her servant's overly adult costume. This is of textbook suitability for the fussy Victorian camera - but less appropriate for a child labourer. The brocaded skirt swamps Nonkosi; unseemly billows (cropped by the frame) trail over the carpet. The item on which peasant eyes focused first (skimming over standardized clothes), the marker of class distinctions, is absent. Ornaments, Nonkosi's instructions from 'Mlanjeni' had run, were to be discarded. No follower of Sifuba-sibanzi was to possess anything elevating them over anyone else. Good Christian whites, regarding ornaments as signifiers of paganism, could only approve. One oddity remains: Nonkosi's mantle is strangely untidy, for a posed photograph. But this does allow viewers to see that she is no longer bare-breasted, and to note her hands, among the few body parts that Victorian feminine codes sanctioned for public display. A child's overt compliance with those who held her in their power seems all but total - except, perhaps, for one tiny signal. Believers had been ordered not to cut their hair, until fathers returned.

What of the more mature woman who, unlike Nonkosi, had lived all her life in precolonial Xhosaland? Having initially been captured by Gawler, she had probably been returned to his hands to be re-interrogated. A particular confession was desired of her: that she, too, had lied, on men's orders. Who were the black men she had allegedly seen, asked Governor Grey from Cape Town, urging reinterrogation. She yielded little. The English, reported a black woman, captured 'the Girl and told her that they would Kill her.' She said she hoped they would. '[S]he was not afraid: she would soon come back.'21 Spiritual faith was unhelpful to men whose prime weapon was bodily violence. Nongqawuse maintained the truth of her visions, frustrated white as well as black men, and was never a state witness.

She was not 'decently dressed' in European clothing either. Instead, she was depicted as violating the rules of the brave new world. Among amaXhosa, a head-covering was mandatory for members of the subordinate sex, above the age of young girls. Nongqawuse's turban signalled ongoing adherence to precolonial codes. So did her kaross. Her male counterparts, who regarded a penis sheath as full dress, had long been buying what counted as 'European clothing' (blankets) for winter. Women were stubborn guardians of custom, never seen outside their homes without their weighty ox-hide cloaks. Covered from the forehead upwards with head-coverings, and from the neck downwards in large karosses, which fastened at the neck and doubled as blankets at night, Xhosa women were said to resemble nuns, and to be as modest as their menfolk were exhibitionist. The sexes were further differentiated: women carried money on their persons. Rows of glittering brass buttons, which doubled as coins and were among the few forms of wealth that the subordinate sex could own, would stud an isibhaca (a leather strip running from neck to ankles down the centre-back of a kaross). Nongqawuse, reported a journalist, was 'dressed in a tanned hide, ornamented with bell buttons' (a normal cloak) for her photograph.22

She was not, however, posed in standard fashion once inside the studio. Look at what you should not be able to see: her money. The brass buttons on her isibhaca lie on her shoulder, instead of running down her back. A misaligned kaross is not the only sign of dishevelled dress. Her cloak plunges down; its folds move towards her nipple. Look, then, at what we are directed to see: the large coverings concealing her breasts - and their long straps. Imagine how these expensive coverings would normally have been worn, one at a time, tied under the kaross not of an intombi, but of the wife of a wealthy man, proudly displaying exceptionally dramatic beadwork, and chain fringes with kinetic visual effects, in the intimacy of her own environment. Absorbing countless hours of female labour, the beads are of unknown colours, but pure white probably dominated. (The beadwork is exceptionally strongly delineated on the negative). Pure white, however, reflected too much light; it was normally almost taboo for studio portraits; black and white combined constituted a photographer's nightmare. Durney was levelling his lens at what one might have thought was triply inappropriate for a colonial cameraman: two breast-covers, of other men's wives, photographing as white and black. These spectacularly anomalous bras - two, draped, on a dishevelled kaross, unnoticed by the press outside the studio, of problematic colours, outside the class and gender brackets of an intombi, who signalled her unmarried status with her turban style - are the focal point of the entire photograph.23

Why was she portrayed dressed in slovenly fashion, wearing illegal attire, flouting all sartorial codes with two draped bras? An ancient technique of ridicule discredits women by impugning their femininity. To this was added racial specificity: 'sexually suggestive poses and careful placement of the beadwork ensured that there was usually a salacious, even pornographic undertone' to many photographs of African women.24 But are two bras - signifying four breasts in the wrong position - on someone whose breasts were routinely naked, salacious? When a celebrity landed up inside a Fancy Case, structurally designed for voyeurism, and was viewed in the home of a widower in army headquarters, in a culture where breasts were sexually charged and black prostitutes thrived, did white men find this pose erotic? I do not presume to know. All I see is a woman framed by enemies. I see an African celebrity in captivity, affording schadenfreude to settlers. The 'young woman who caused so much sensation among the Kafirs by the fabrication of wonderful visions,' noted the press, was among the 'notable persons' visiting Durney's studio. She 'has been "taken" by order.'25 I see a female detainee being 'taken' by a mountebank with a history of exploiting black breasts, creating emulsions on glass which recorded his own visions of the sexualized grotesque. I see, located in a visual culture that read photographs in the languages of painting and literature, a before-and-after morality tale. One woman, indecently dressed, represents the sexualized precolonial African pole; the other, a servant in Victorian attire, epitomizes the colonial success story. The past and the future touch - and the past is risible, freakish, as vice is to virtue, with coins on her shoulder and loose bras on her breasts. I also see a fabrication guaranteed to amuse good Christian whites. Whom had tens of thousands of blacks been awaiting? Christ/Sifuba-sibanzi/the Broad-Chested One. Whom did they receive? A female detainee draped with two outsize bras. Political prisoners posed before a phallic lens, used as props to convey imperial triumph, colonial propaganda and a blasphemous visual pun: I can see nothing but the vulgarity and sexualized viciousness of victors.

Reinventions

This photograph of a domestic worker, a detainee and two bras is iconic. It has been disseminated globally, in media including literature, the press, visual arts, reference works, scholarly texts; it sits in many museums, picture libraries, homes. Consider some verbal frames.

Portrait of Nongqause the prophetess.26

They live with [Mrs Gawler] and her husband ... She dresses them nicely in colourful dresses. Young prophets in summer dresses. She and Dr Fitzgerald ... take the prophetesses to a photographic studio for their portraits ... They do not know how to smile ...27

Nongqawuse (right) c.1858. The young woman's prophecies spelled catastrophe for the Xhosa nation ...28

Black Woman in Turban & Blanket with Decoration with Long Hanging Fringes, & Black Child in Western Dress & Shawl.29

A remarkable ... photograph ... of the two cattle-killing prophetesses ... [taken] in Grahamstown ... while they were staying with Major John Gawler and his wife. Their costume apparently consists of miscellaneous bolts of cloth.30

Nongqawuse and Nonkosi (Prophetesses)

Correct view: Nonkosi = left hand side

Nongqawuse = right hand side31

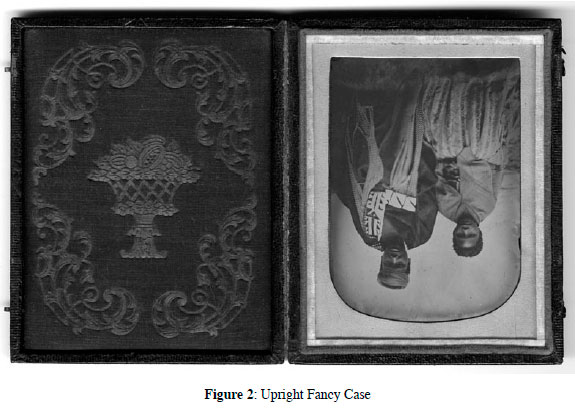

Four points can be made about standard verbal frames supplied by those familiar with the image. First, little is noted of the broader context: martial law in a British colonial capital, where epochal victory was being consolidated by cultural means. Second, although the image is as little a portrait of its sitters as an advertisement is a portrait of its models, locating it within this genre is commonplace. Moreover, although the lens was aimed at two women, and the image pivots around their contrasts, the intombi with the bras is often singled out as the only significant figure. Third, many captions are careless. The sixteen lines above provide inaccurate geography, anachronistic history, faulty occupations, fallacious dress and a problematic visual genre. Fourth, matters specific to female subjects pose particular difficulties. Normal attire appears terra incognita; abnormal attire evokes no comment. Almost any Xhosa woman in colonial eyesight was likely to be enmeshed in cheap labour - yet a domestic servant is called a prophetess. Sexing two people using archaic language is ubiquitous (prophetesses); sex is thus constructed as (somehow) integral to catastrophe; no such enthusiasm exists for decoding the centrality of gender in this image. The net result is that political prisoners, en route from military prisons in one colony, via a warlord and a studio, to a 'Female Kaffer Prison' in another, are termed 'prophetesses', 'staying' with their interrogator's family as if they were guests enjoying a photo-opportunity. If the first make-over occurred when two women fell into the hands of armed men, the second began as intellectuals refashioned them.

The story does not end here: ifoto was reinvented. Over the next 150 years, two people who entered a hotel possessing little but their bodies began appearing in visuals with physical features other than their own. Virtually all that remained constant were masculinist frames and the presence of female underwear.

Some three decades after organizing the photograph, Superintendent FitzGerald began releasing copies, urging others to write the history that he never would. A King William's Town editor took up the challenge, publishing an 1891 fictionalized history, Pambaniso, subtitled Scenes from Savage Life. Times, however, had changed. According to his overarching theme, young Xhosa women were delectable; white men lusted after them; they deserved rescue from their savage menfolk. Nonkosi and Nongqawuse, in particular, had been but the innocent pawns of their insane uncles. Moreover, they had aided the cause of civilization: 'Kaffirs' began working for Europeans, 'whom they began to like as masters.'32 The photograph, positioned at this point, as Savage Life ended, was prepared for print by a London sweat-shop, better known for engraving cartoons for Punch. Graphic satirists were now faced with fictionalized history about savage men, wenches needing saviours, and photographs intended to fit this frame.

The image depicting the pawns was already one or more generations removed from an optical illusion in a Fancy Case, and many more from its female subjects.33 London's function was to distance it even further. In order for photographs to be reproduced, cheaply, in black printer's ink, on poor quality paper, they were translated into a different syntax (dots), and a different medium (metal), by rephotographing them through a coarse optical grating onto metal. Large transformations occurred. The technique was still in experimental phases; photo-engravers drew on older practices. Engravers invariably departed from photographs; photographers routinely doctored portraits. '[I]f the camera was a sentient thing it would not know its own offspring,' it was noted in 1890; 'a portrait not worked on ... is considered coarse.'34 These London men were located in a graphic tradition ideal for the author. It revolved around making portraits more picturesque, drawing on gendered metropolitan stereotypes - and could not black wenches do with such a make-over, if readers were to find them alluring enough to rescue from their dark background? From this perspective, the sweat-shop generated an adequate image.

Try adopting Nongqawuse's pose: your nose aligned with your right shoulder, your left shoulder sloping downwards, staring straight ahead but sideways, the shadow on your left hip changing abruptly into light, many chains running horizontally. Only graphic manipulation could create this implausible woman. London proudly advertises its contribution. The signature in the right-hand corner declares, with a flourish, that the image owed its existence not to the colonial camera, but to metropolitan engraving techniques ('Sc'). Whether blind seers were the best advertisement for imperial carving skills is another question. Nongqawuse, cut down to size, has lost her neck, together with her commanding height, age, bulk. No longer staring directly at us, she has acquired the faraway look of a clichéd visionary. The bras are now dazzling white, and approach exotic ornamentation of a kaftan. Photo-engravers had worked away at metal, removed the grey effect of the grating, together with beads, patterns, chains. Nongqawuse à la London now bears closer resemblance to an anglicized Nonkosi, rather than looming large as risible precolonial African womanhood. According to the caption, she is implicitly Nonkosi.

A pair of prophetesses was also created by reshaping the smaller figure. Nonkosi, lacking a head-covering but trussed behind textiles, looks older and less vulnerable to an ignorant metropolitan eye (thirteen to her companion's seventeen, reads the text). Originally, her overskirt displayed no border; her skirt fell flatly downwards, trailing on the carpet. Here, she has been accorded Madam's style and stance. She balloons out, in tiered bordered overskirts (carelessly retouched, one simply petering out). A visual dress code is at play. She could bulge out in this fashion, in this period, only if wearing a notorious steel cage: a skeleton skirt, a crinoline. The hoops now prominent on her skirt resemble crinoline hoops; the vertical stripes resemble its ribs. Viewers are being visually informed as to what this maid is wearing underneath - and, since she is handless and somewhat vulgar, virtually on top. Her underwear, too, is now critical to her appearance and her meaning. A woman (implicitly Nongqawuse) wearing a petticoat of steel carried multiple connotations. So did a prophetess precipitating a holocaust while wearing a skeleton skirt.

A settler fiction called Pambaniso - Turning Upside-Down - thus carried an image appropriate for its title, genre, themes and graphic satirists: savages had somehow given birth to anglicized prophetesses in incredible unmentionables. Historians, however, soberly republished ifoto as fact. Nongqawuse, according to an encyclopedia, was the crinolined tub. In the late twentieth century, the skeleton skirt was cropped. Nonkosi's guillotined head with death-mask eyes, labelled Nongqawuse, conveyed disaster more successfully. Authors selecting the neck-less wonder instead, and stressing that Nongqawuse was young and credulous, also found this image helpful. Its credibility was invariably enhanced by two omissions: its origin in a fiction about savages; the signature of draughtsmen for Punch.35

This descendant of the original illusion was, however, problematic when republished, since passing it through a second optical grating tended to produce a sooty morass. In the mid-twentieth century, yet another King William's Town man, a doctor, attempted something different. Inspired by Superintendent FitzGerald, he wrote 'Cauldron of Witchcraft'. This fictionalized history of millenarianism was framed as barbarians moving from darkness into light. Published in a book aimed at tourists, it possessed an illustration, supposedly depicting the most powerful women ever born to the gullible Bantu.

Viewers might bear in mind the problems of fitting a Victorian image, lifted from a text encouraging masters to save maidens, into a new frame called 'Cauldron of Witchcraft', aimed at tourists in apartheid South Africa. These proved insurmountable. An Africanized déclassé image was, however, attempted. The error-ridden caption has one virtue: an ancient wood-cut sounds more African than an airbrush, applied to half-tone London print. The visual might be called primitive in itself. Painted nature has appeared. A hotel room, a Victorian frame, a crinoline, brocade and an industrialized grid have almost disappeared. Perhaps the best that can be said for Nongqawuse is that she is now Ophelia in Africa. As for the candy-striped figure (implicitly Nongqawuse): follow the V-shapes down, from the new white neckline, to the new folds in what resembles a poncho, to its new V-base, to its gap, to - her genitals. This tawdry image shifts the sexual focal point away from breasts, towards another bull's eye.

This paintograph was remarkable for the enthusiasm with which Africanist historians greeted it. A crude fake, in a settler fiction called 'Cauldron of Witchcraft', above an error-ridden caption, lacked obvious reliability. Yet this was often the preferred image, chosen above all others. It appears in a bestseller: the Reader's Digest Illustrated History of South Africa (with eminent historians as consultants). Over 85,000 copies were sold within six months of its 1988 edition; updated versions were produced in 1992 and 1994. All carried the same cropped detail. 'NONGQAWUSE'S prophecy spelt disaster for the Xhosa', reads the caption, beneath Ophelia in an icing sugar turban. One can well believe it.37 In an even more effective visual, an American journal displays an enlarged mugshot of Nonkosi. She apparently wears shades and a V-neck sweater. These, combined with leprous splotches and criss-cross lines, create a guillotined gorgon, transcending period or locale, labelled Nongqawuse.38

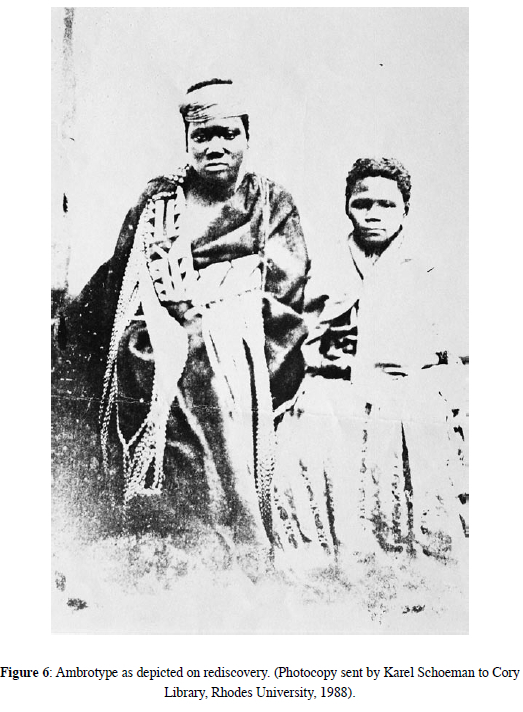

By this time, historians had little excuse for republishing anything remotely descended from Scenes from Savage Life. In 1988, the National Library of South Africa sent its collection of old photographs for cleaning. Five ambrotypes depicting blacks were discovered: they had seemingly been lurking in one of many forgotten corners. Nothing was known of their provenance; the dead had simply appeared.39 One depicted women; attempts were promptly made to identify them. A photocopy, sent to leading academics and archivists, seems to be the only record of their then appearance.

Three striking features are apparent. First, all prior reproductions had been mirror-reversed. This portrays the women as they faced a hostile lens. Second, Nongqawuse's is'thunzi (aura) is different. This is no Ophelia. Instead, a political prisoner glowers at us, oozing misery and antagonism. Third, surreal lighting enhances her sullen intensity. A poor photocopy probably contributed - but backings for negatives also deteriorated over time, dramatically affecting the positive. Moreover, the original was created by an artist, a mountebank, who manipulated the tools of his trade (which allowed photography of 'ghosts'). This image, with its unnatural chiaroscuro, depicting a Fury and her 'bearded' acolyte, whose Victorian body is vanishing, is the only one with Durney's familiar gothic signature. His original was no pretty picture. He was taken aback, declared an eminent Victorian, to see 'two such ... ugly Girls'.40 It is also the only image that evokes millenarianism, and suggests apocalyptic obliteration and genocidal rage.

The ambrotype was immediately recognized as more reliable than cute feminized fabrications - but only slowly displaced them. A bastion of resistance was breached fifteen years after its rediscovery, when the leading scholar of Nongqawuse and the movement finally ceased republishing a fake (the paintograph). He urges us, however, to forget about the 'authentic photograph'. Nongqawuse, he insists, was a little pre-pubescent girl, an intombazana, like Nonkosi. The ambrotype version he publishes is cropped, to heads-and-shoulders. Editing and selective use of sources were clearly crucial, within a frame which infantilized women.41

Forgetting about the 'authentic photograph' had already occurred: the rediscovered positive had disappeared. Passive neglect is perhaps the best of all possible fates for an old cased photograph; surgery, unfortunately, often occurs. Five years after the dead had been resurrected in a library, the previous cleaning process was found to have been disastrous. Restorers intervened. The Fury had already vanished. The Fancy Case was further altered: the glass negative was flipped over, and accorded a new backing. More recently, the glass was again removed - and replaced upside-down.42 Figure 2 depicts the most up-to-date version of one of the earliest surviving photographs of black women in southern Africa: inverted, mirror-reversed, with a modern backing turning whites into blacks, blacks into whites, crisply.

These changes created new positives. They had a cascade of consequences: particularly for societies which, like most in Africa, strongly code white and black, left and right, inverted and upright, and value a person's is'thunzi. Compare the is 'thunzi of an inverted Nongqawuse with that of the woman radiating hostility when the ambrotype was discovered (Figs. 2 and 6). Curators of historic images clearly ought to acquire recognition as creators of new ones. In the case of this iconic photograph, the effects rippled through the globe - with a twist, since, as history demonstrates, many people have difficulty telling two African women apart. Ifoto had been reversed; its verbal frame had not. In the millennial year, on the cover of an award-winning work of historical fiction, ifoto appeared in reverse, with the old caption. Nongqawuse, claims the author, was a waif, unlike the fashionable Nonkosi. She wends her way through his text and the world with the body of an anglicized child, destroying an African nation.43

Nearly 150 years of reinvention fuelled a broader phenomenon. For a century after the millenarian movement, black men publicly commented on it. They included contemporaries, traditionalists, trade unionists, historians, leading intellectuals: men like Herbert Dhlomo, W.W. Gqoba, John Jabavu, James Jolobe, A.C. Jordan, S.E.K. Mqhayi, Paramount Chief Sarhili, Tiyo Soga, J.H. Soga, Benedict Vilakazi. They were operating in masculinist domains, discussing 'the Nongqawuse' (as it was termed in isiXhosa). Not one in this galaxy proposed what is today the hegemonic popular explanation for causation. Not one suggested that Governor Grey had manipulated Nongqawuse to prophesy as she did.44

This hypothesis burgeoned subsequently, under the apartheid regime. A crucial cause was a countrywide assault on black peasants: cattle-culling, and restrictions on agriculture, forcibly imposed by the state. This was often called the second Nongqawuse. That the colonial state had underpinned the first Nongqawuse became plausible. To this reinterpretation (strongly promoted by anti-apartheid intellectuals) were added extensive comments about the one thing that interests many people about women: their appearance. Although the ambrotype had depicted an intombi wearing a turban, kaross, isibhaca, breast-covers and necklace; although the earlier wave of secondary literature by African authors had often construed Nongqawuse as attractive, traditionally attired, persuading men into foolish actions through her sexuality, she, it now began to be said, had been ugly, unAfrican. She had worn neither traditional garments nor ornaments. She had been attracted by whites' clothes. When they bribed her, with their clothes, she 'glistened in her whiteness'. The 'little girl' became a 'white woman', spreading their message.45

Corrupt visuals and captions did, indeed, frequently create someone who glistened in her whiteness. They did so when many South Africans had little but textbook knowledge of pasts so different from their presents. When a white political activist, writing an alternative history to racist school texts in 1952, under a vernacular pseudonym, publicly declared that Nongqawuse had been Grey's pawn, his interpretation fell on fertile ground.46 It was underpinned by the second Nongqawuse. It was increasingly offered by others. It was reinforced by widely disseminated images - of enormous import in cultures in transition to literacy - which depicted a Nongqawuse who, at no stage, looked like a normal intombi, and was instead crinolined, kaftaned, candy-striped, Ophelia, an anglicized waif. A century of different explanations by black intellectuals began evaporating. The Grey Man Theory of History - profoundly shaped by make-overs of black peasants by white men - is today regarded as the African perspective on the tragedy. In one of history's ironies, Africanist credentials are demonstrated by positioning a precolonial woman within a frame popularized under apartheid.

Conclusion

When an iconic photograph related to southern African visionaries is reproduced, modern frames have discreetly replaced the original. I found it illuminating, however, to retrieve a Fancy Case from the dustbins of history (a library basement). An optical illusion surrounded by garish signifiers of imperial dominance failed to suggest an authentic photograph of peasant prophetesses. Instead, it sparked my interest in the relationship between reframing and revision. When frames change, spectacular shifts can occur in focal points, visibility/invisibility, appearances, connotations.

My own attempt at reframing has involved placing images back in the historical contexts in which they were created - rather than treating them as though they fell from the sky into a picture library or onto a page. In addition to the immediate circumstances in which various visions were generated, epochal transformation existed, as a precolonial peasantry was smashed, faded from collective memory, and survived only in attenuated forms ill-equipped to illuminate people at the bottom of gender, racial, class, generational and geopolitical hierarchies. When two political prisoners were posed in a British colonial capital in 1858, the camera was following the gun into a devastated landscape. The diseased society into which the sitters had been born was dead. I see, imprinted on glass, a triumphant vision of a virtuous domestic worker and an indecent precolonial charlatan: not peasant prophetesses, who never entered the room. Within three decades, as London contributed to Scenes of Savage Life, an entire world was passing into racist, masculinist history. Who still knew what it meant to rise at cockcrow, tie on a labour-intensive beaded breast-cover, put on a kaross studded with button-money - and face another day when British barbarians might descend? As this world evaporated, many verbal frames for the image, lacking ballast, floated into alien stereotypes. Antiquated beadwork no longer suggested breasts, let alone gendered ridicule or a blasphemous pun. The figures no longer represented the risible precolonial past and the laudable colonized future: they both looked archaic. They became a pair of interchangeable prophetesses, positioned within modernized masculinist frames and industrialized visuals: ersatz ones, not least mass production imposed and facilitated distance from an optical illusion. In this brave bourgeois world, a woman who was allegedly of epochal significance, her name stamped upon a mass movement of dimensions and impact seldom attained in southern Africa, proved powerless. A sexualized precolonial freak reappeared in London's Victorian version, apartheid' s Africanized version, post-apartheid's infantilized version. The figures became crusted over with accretions. The Victorian domestic worker of 1858, having passed through a Fancy Case, Scenes of Savage Life, 'Cauldron of Witchcraft', an Africanist academic text and a radical journal, emerged in 1990 in the United States, in an article discussing the Grey Man Theory of History, as Nongqawuse wearing shades and a V-neck sweater.

Reinventions were bridled, not halted, by the 1988 rediscovery of a negative created by a mountebank. Technicians updated one of the earliest surviving photographs of black southern African women with Orwellian ease. Verbal frames blind to gender-specificity - and individual specificity - continued. At no point has it been noted that images depict a domestic worker, a detainee and two bras. At no point has it been suggested that they all portray not leaders of an anti-imperialist movement, but the triumph of victors over African women swallowed into an alien order.

Another feature has remained constant: for almost 150 years, predominantly white male image-makers have fiddled with two Xhosa girls. One might be forgiven for wondering why this activity has proved so appealing. Nongqawuse's uncle and his female couriers operated as popular seers for about nine months. Nonkosi's uncle and his friends produced community theatre for an even shorter period. They all entered a millenarian movement that had originated six years earlier, extended over vastly broader terrain, and had all its central causes, prophecies and commands in place. The prime innovation of an intombi and intombazana lay not in cattle-killing, not in new prophecies, not in transmission of the words of a British Governor, but in visual politics. They were literally seers, telling of black fathers whom the polluted could not see. Visuality - which was directed outwards towards patriarchs, outwards in space, backwards in time, and was independent of industrialized media - proved extremely popular. Why, then, are audiences for whom visual languages remain central subjected to wearisome reinvention of ifoto? Where are the images depicting the single most important cause of all that followed: the tidal wave of red, pulverizing precolonial societies? Where are those depicting battalions pouring off ships? From beginning to end, the coincidence between panics that the land was about to be killed, and self-destruction of peasant resources, was total. White male militarism catalyzed upsurges of millenarianism: not black women. Where are images of the iconic seer? Dr Mlanjeni kaKala set the prophetic agenda for almost everything that followed, as contemporaries well knew. (' Isanuse u Mlanjeni sawucitacita umzi.' 'The diviner Mlanjeni destroyed the nation.') Death proved no bar to his towering over other visionaries: it was precisely what saved him, like Sifuba-sibanzi, from obsolescence. Ordinary seers, who typically had very short shelf-lives, had nothing on an eternal male messiah, structurally incapable of ever being out of touch with peasants in search of an apocalypse.

The iconic prophet, the central catalyst, the prime cause: these are conspicuous by their almost complete absence from visual (and often verbal) depictions of this movement. Standard interpretative frames are different. They rely on gendered criteria to periodize history into masculine and feminine segments: war (Mlanjeni), and catastrophe (Nongqawuse). A millenarian unity is thereby fragmented, facilitating a close-up, a mugshot. Placed centre-stage is the anti-heroine, who, in the nine months she operated at the tail-end of a much bigger movement, angered patriarchs, and then had a mass movement collapsed onto her person. She, we are told, was 'the young girl whose fantastic promise of the resurrection lured an entire people to death.'47 It is as if a story were told about Mary Magdalene and her fantasies of resurrection: a tale which drastically cropped John the Baptist, Jesus, his twelve disciples, and the Roman empire.

One day, it might be safely prophesied, the world with which we are familiar will end. There may come a time when those framing the African female past have certain skills: can tell two women apart; can distinguish them from their enemies; can position them within time-frames; can interrogate stereotypes and forgeries; can even lift their eyes from breasts towards invisible men with bloodstained hands. That day is still distant. In the meantime, a colonial vision, depicting political prisoners posed before a phallic lens, is hailed as an authentic portrait of peasant prophetesses spelling catastrophe. I can make only one small reformist suggestion. If placing images in their historical context is important, could not the authentic ifoto be presented within its authentic Fancy Case? Popular enthusiasm for updating the past can be accommodated, with the most up-to-date version of the frame. The image in Figure 2 has a further advantage. Consumers of visuals and African histories have been jaded by long years of swallowing the incredible - but this image has a certain novelty. A sexualized colonial vision originating in British army headquarters is, it seems to me, adequately represented by a vulgar metallic and maroon frame, specifically designed to turn an emulsion into an illusion, in which African women are upside-down.

* Many people have helped me in writing this article or obtaining visuals: my particular thanks to Andrew Bank, Jane Bennett, John Dwyer, Raymond Mtati, Mary-Lynn Suttie and Lance van Sittert.

1 King William's Town Gazette (hereafter KWTg), 21 Aug. 1858.

2 M. Bull and J. Denfield, Secure the Shadow (Cape Town: T. McNally, 1970), 192. [ Links ]

3 Library of Parliament, Mendelssohn Collection, 'Native Races of South Africa' album.

4 National Library of South Africa (NLSA), Grey Collection, MSB 223(2), FitzGerald to Grey, 28 November 1886.

5 Cape Archives (hereafter CA), Government House (hereafter GH) 8/50, J. Maclean to G. Grey, 24 Sept. 1857.

6 CA, Colonial Office (hereafter CO) 739, Acting Superintendent of Kaffirs to Colonial Secretary, 25 Feb. 1859, with enclosure.

7 N. Mostert, Frontiers (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1992), 932.

8 M. Lelilo, The Question of Lesotho's Conquered Territory (Morija: Morija Museum and Archives, 1998), 27. [ Links ]

9 J. Lewis, 'An Economic History of the Ciskei, 1848-1900' (Ph.D. thesis, University of Cape Town, 1984), 717. [ Links ]

10 During Mlanjeni's 1850-3 war, the most important were Mlanjeni and a female diviner in LeSotho. During the 1854-6 Crimean war, perhaps a dozen new seers emerged in Xhosaland. During the war panics from mid-1856 to early 1858, the most popular were Nongqawuse's uncle and Nonkosi. Members of their homesteads, and about seven others elsewhere, were also active.

11 Autobiographie de Mme Rosette Schrumpf (Strasbourg: C. Schrumpf, 1863), 72.

12 CA, GH 28/71, Illegible to His Excellency, 15 Oct. 1856.

13 Graham's Town Journal (hereafter GTJ), 6 Nov. 1852.

14 GTJ, 17 Sept. 1853.

15 CA, GH 28/71, Illegible to His Excellency, 15 Oct. 1856.

16 Mostert, Frontiers, 1190.

17 M. Berning, ed., The Historical "Conversations" of Sir George Cory (Grahamstown: Maskew Miller Longman, 1989), 128. [ Links ]

18 Imvo Neliso Lomzi, 5 Nov. 1896. ('The diviner Mlanjeni completely destroyed the nation. At the time of Nongqause the nation was convinced by the diviner's word, that for the day of 18 February 1857, when the dead would arise, whites be driven into the sea, and be drowned, cattle had to be killed, sorghum discarded, and fields left untilled').

19 CA, King William's Town (hereafter KWT) records, I/KWT 4/1/3/33, examination of Mame, 12 March 1858.

20 CA, British Kaffraria (hereafter BK) 109, GN 12 of 1858.

21 U. Long, ed., The Chronicle of Jeremiah Goldswain, vol. 2 (Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society, 1949), 193. See also CA, GH 8/35, documents submitted to Grey, 12 April 1858.

22 KWTG, 31 July 1858. See also J. Backhouse, A Narrative of a Visit to the Mauritius and South Africa (London: Hamilton, Adams, 1844), 183; E. Shaw and N. van Warmelo, 'The Material Culture of the Cape Nguni', Part 4, Annals of the South African Museum, vol. 58 (4), 1988, 469, 474-5, 480.

23 Thanks to Patricia Davison, Lindsay Hooper, Carol Kaufmann, Pam Stallebrass and Michael Stevenson for comments about these breast-covers.

24 M. Stevenson and M. Graham-Stewart, Surviving the Lens (Cape Town: Fernwood, 2001), 21.

25 KWTG, 31 July 1858.

26 Bull and Denfield, Secure the Shadow, 192.

27 Z. Mda, The Heart of Redness (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 317-318.

28 C. Saunders, ed., An Illustrated Dictionary of South African History (Sandton: Ibis, 1994), 186.

29 NLSA, catalogue entry for DAG 8327.

30 Mostert, Frontiers, np, caption for the photograph.

31 NLSA, caption for photograph in portrait collection.

32 T. Beattie, Pambaniso (Cape Town: J.C. Juta and Co, 1891), 228.

33 More than one glass negative may have been created at the original sitting; the firm may have received an image depicting a different pose.

34 H. Henisch and B. Henisch, The Painted Photograph 1839-1914 (University Park, Pa: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996), 57.

35 J. Burman, Disaster Struck South Africa (Cape Town: Struik, 1971), 5; J. Bergh and A. Bergh, Stamme & Ryke (Kaapstad: Don Nelson, 1984), 50; Reader's Digest Illustrated Guide to Southern Africa (Cape Town: Reader's Digest Association South Africa, 1994), 402; Standard Encyclopedia of Southern Africa, vol. 8 (Cape Town: Nasionale Opvoedkundige Uitgewing, 1973), 220; G. Weldon, George Grey and the Xhosa (Pietermaritzburg: Heinemann-Centaur, 1993), 19. (Both Bergh and Weldon use a further retouched version.)

36 A. Burton, Sparks from the Border Anvil (King William's Town: Provincial Publ., nd, c1950), 48-49.

37 Reader's Digest Illustrated History of South Africa (Cape Town: Reader's Digest Association, 1994), 137.

38 J.B. Peires, 'Suicide or Genocide? Xhosa Perceptions of the Nongqawuse Catastrophe', Radical History Review, vol. 46/7, 1990, 48. For other uses of this paintograph, see J. Milton, The Edges of War (Cape Town: Juta, 1983), 233; New Nation, New History, vol. 1 (Johannesburg: New Nation and History Workshop, 1989), 51; J.B. Peires, The Dead Will Arise (Johannesburg: Ravan Press, 1989), facing p.160; J. Brown et al., History from South Africa (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991), 29.

39 'Notes and News', Quarterly Bulletin of the South African Library, vol. 47(4), 1993, 125-127, makes a suggestion about provenance.

40 NLSA, Grey Collection, MSB 223(2), FitzGerald to Grey, 6 March 1895.

41 J. Peires, The Dead Will Arise (Johannesburg: Jonathan Ball, 2003), 160, 375. Peires was aware of the ambrotype from 1988: see SANL, Background file on INIL 8327 (DAG), J. Peires to K. Schoeman, 14 Sept. 1988.

42 SANL, DAG file, Report on 1993 restoration processes. On principle, believed these restorers, ambrotypes should be laterally reversed. The principle is modern. Even if conservation reasons exist for laterally reversing Victorian originals, copies need not be mirror-reversed. The inverted version appeared in 2004.

43 Mda, Heart, 59, 182-3. In 2004, the library reversed the caption.

44 Imvo Neliso Lomzi, 1 Oct. 1896-19 Nov. 1896; Isigidimi SamaXosa, 1 March 1888, 2 April 1888; J. Chalmers, Tiyo Soga (Edinburgh: Elliot, 1878), 139-149; H. Dhlomo, The Girl Who Killed To Save (Lovedale: Lovedale Press, nd, c1935); J. Jolobe, Ilitha (Johannesburg: Afrikaanse Pers Boekhandel, 1959; reprinted 1971), 43-61; A.C. Jordan Ingqumbo Yeminyanya (Lovedale: Lovedale Press, 1940); S.E.K. Mqhayi, Ityala Lama-Wele (Lovedale: Lovedale Press, nd, c1938), 64, 165; J.H. Soga, The South-Eastern Bantu (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1930), 161, 237, 242247; J.H. Soga, The Ama-Xosa (Lovedale: Lovedale Press, nd, c1931), 103, 122; T. Soga, Intlalo Ka Xosa (Lovedale: Lovedale Press, nd, c1938), 174-179; B. Vilakazi, Inkondlo kaZulu (Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1935; reprinted 1965), 3-10. According to Mqhayi, acclaimed as one of the greatest Xhosa historians, Grey was an 'iqawe', an outstanding man (Umteteli wa Bantu, 8 Nov. 1930.)

45 H. Scheub, The Tongue is Fire (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1996), 308. See also Jolobe, Ilitha, 44; V.C. Mutwa, Africa is My Witness (Johannesburg: Blue Crane, 1966), 295; G. Sirayi, 'The African Perspective of the 1856/7 Cattle-killing Movement', South African Journal of African Languages, vol. 11(1), 1991, 42.

46 Mnguni [H.Jaffe], Three Hundred Years (Cape Town, 1952), 88.

47 Peires, Dead, 2nd ed., 11.