Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.29 no.1 Cape Town 2003

ARTICLES

The bourgeois eye aloft: Table Mountain in the Anglo urban middle class imagination, c.1891-1952

Lance Van Sittert

University of Cape Town

Reading Table Mountain

South African environmental history has thus far been almost entirely preoccupied with tracing the white settler-cum-South African physical impress on the environment, although the latter has also been identified as a key site of ideological engineering in the forging of new imperial and national identities in the global European diaspora.1 Analyses of this process have emphasised the eye as the determinant sense in the construction of these new 'imagined communities' and the seemingly innocuous act of looking - at people, plants, animals and landscapes either in nature or reproduction - as political and hence deeply implicated in the ultimate physical domination of the objects surveyed.2

Much of the historical scholarship on this purportedly hegemonic imperial-cum-white-nationalist 'gaze' in South Africa, however, is reminiscent of the earlier Poulantzian detour in its obeisance to imported theory, cavalier attitude to empirical evidence and ultimately formulaic readings of the past which confirm rather than disrupt the conventional wisdoms of social history's political-economy narrative3. Secondly, the scholarship of the gaze suffers from the same malaise that Cooper identified as afflicting the historiography of decolonisation, that of 'hindsight' or the elision of political traditions and identities that were neither 'imperial' nor 'national'.4 Nor is the remedy just a matter of adding 'native voice', for as Merrington has shown, the imagined community of white South African nationalism was an ocular Tower of Babel in which rival ethnic, class and other visions were continually contesting and realigning the master gaze.5

These problems are reproduced in microcosm in the recent historical scholarship on Table Mountain, which predictably reads the visual imagery of the mountain as a reflection of a hegemonic European imperialist-cum-white-nationalist gaze.6 The preference for 'spatiality' over 'temporality' in this literature produces a history of the mountain that is as two-dimensional as its primary source.7By recognising that European settlers did not share a single unified gaze, but rather one fractured along lines of class, ethnicity and gender and that the mountain had more than one 'face', it becomes possible to offer an alternate historicised reading of imagery contigent on context. I attempt to do this here by tracing changing images of the mountain from the mid-seventeenth to the mid-twentieth century, but focusing particularly on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The Mountain Wild

Prior to European settlement Table Mountain provided a handy landmark and prospect by which seafarers could locate and orientate themselves in an unknown ocean, Antonio de Saldanhar making the first recorded European ascent in 1503. Following the Dutch East India Company's (DEIC) establishment of a permanent settlement at Table Bay in 1652, the mountain prospect acquired a new military significance. The Company defended the Cape Peninsula as if it were an island, fortifying its most obvious maritime approaches at Camps Bay, Hout Bay and Muizenberg and attempting to complete the sea moat by breaching the broad isthmus between Table and False Bays with a canal 'deep and broad enough for Two Ships of the heaviest Burthen to pass by one another.'8 The slopes above Table Bay were also dotted with forts and signal stations established on Lion's Head and Signal Hill to provide early warning of and to approaching vessels.9

Beyond the borders of settlement, however, the peninsula's mountain massif remained a wilderness outside of DEIC control reputedly haunted by 'noxious and destructive animals that shun the light' and 'a kind of enemy still more dangerous ... fugitive slaves.'10 Excursions to the summit were thus feats of masculine endurance in defiance of such dangers. Le Vaillant accordingly armed himself with a double-barrelled shotgun, two pistols, three dogs ('the choicest of my pack'), two slaves and a 'Hottentot' and maintained a large fire at night to ward off evil.11 The dangers were more imagined than real, however, having to be construed out of cries, howls, tracks and the remains of fires and food for want of any actual attack by either animals or maroons on sojourners at the summit.12 What predators there were on the mountain, subsisted by raiding along the margins of the settlement not on the summit itself and few survived for long at this deadly interface.13

The reality of the summit was more prosaic constituting a commons worked by the slaves of Cape Town who were reportedly 'thoroughly inured to the hardships of mountain climbing.'14 By the mid-eighteenth century, '[m]any slaves ... when weather permitted, made daily journeys across the mountain [from Cape Town] and returned with a load of timber, generally of the kind suitable for waggon-making.' The timber was produced by fugitive maroons: 'In return for some bread, meat and fish these outlaws would cut the trees down in the valley [on the False Bay side], hew them to shape and drag them up to the crest of the mountain'.15 By the close of the eighteenth century the mountain's dwindling wood supply was being energetically harvested for fuel to the extent that:

In most families a slave is kept expressly for collecting firewood. He goes out in the morning, ascends the steep mountains of the peninsula, where wagons cannot approach, and returns at night with two small bundles of faggots, the produce of six or eight hours hard labour, swinging at the two ends of a bamboo carried across the shoulders. Some families have two and even three slaves, whose sole employment consists in climbing the mountains in search of fuel.16

It was this ceaseless scavenging for wood, not sightseeing, that produced the indelible 'marks of the Human footstep' seen by Lady Anne Barnard on her ascent of Platteklip Gorge in the late 1790s 'in the great quantity of old soles and heels of shoes' littering the route.17

The transfer of control over the Cape Colony to British hands at the turn of the eighteenth century coincided with tectonic cultural shifts around the north Atlantic rim towards empiricism and romanticism, simultaneously elevating mountains into legitimate subjects for scientific enquiry and sites for experiences of the sublime.18 It was in this new cultural context that Table Mountain came to be imagined from the late eighteenth century as a site of scientific and romantic pilgrimage for Cape Town's itinerant intellectual and administrative elite. The majority ascended on foot via one of two routes; through the 'door of the mountain' - the 'broken and dilapidated stairway' of Platteklip Gorge - or Constantia Nek, the latter having the advantage of being partly negotiable on horseback.19 They did so preferably in large parties, which included hosts of slave, 'Hottentot' and 'coolie' retainers to serve as porters, cooks, guides and protection. Expeditions were mainly confined to summer and parties usually embarked well before dawn in the hope of seeing sunrise from the summit and avoiding climbing during the heat of the day. The ascent could take up to five or six hours and the exhausted bourgeoisie were revived for the descent with alcohol, siestas and hot dinners atop. Before leaving they gathered souvenirs - 'little white pebbles . to make table mountain earrings to give to my fair European friends' - and added their names to a spreading rash of graffiti.20

The North Face, or the Mountain Sublime

Despite the random and informal nature of these pilgrimages, the new cultural conventions that guided them lent them a coherence, which reconstituted the mountain as a site of elite learning about the natural world, but more importantly about the inner self.21 The key prospect for instruction was the north face overlooking Cape Town and Table Bay, being both that most immediately to foot from Platteklip Gorge and that which offered the clearest view of the African landscape from the 'stupendous precipice' of the mountain's 'immense wall'.22 Other prospects were less likely to be sought due to distance, fatigue and the want of a discernible European impress on the landscape to focus the gaze and so the view from the north face came to be the sui generis Table Mountain prospect.

For the growing number of bourgeois questers who sought out this view from the end of the eighteenth century onwards, the attraction was 'curiosity' -' seeing what is seldom seen' - rather than 'the more laudable desire of acquiring information', though the former motive was often dressed up in the scientific garb of the latter.23 To the merely curious as opposed to scientific eye, the summit presented 'a dreary waste and ... insipid tameness' after Platteklip Gorge's 'dark caverns, massy columns, long pillars, and light slender arches ... the whole adorned and connected with all the fantastic fret work of gothic architecture', but 'the great command given by the elevation' enabled 'the eye, leaving the immediate scenery ... [to] wander with delight round the whole circumference of the horizon.'24 The view thus revealed had a physical impact on the expectant bourgeois gaze, being experienced as a coup d'oeil or literally a 'blow to the eye', which in Lady Anne Barnard brought to my awed remembrance, the Saviour of the world presented from the top of 'an exceeding high mountain' with all the Kingdoms of the Earth, by the Devil, nothing short of such a view was this - but it was not the garden of the world that appeared all around; on the contrary there was no denying the circle bounded only by the Heaven & Sea to be a wide desart - bare - uncultivated - uninhabited - but Noble in its bareness & (as we had reason to know) capable of cultivation from its soil which submits easily to the spade & gratefully repays its attention.25

The magnification of the bourgeois self by the summit on rare occasions also assumed physical form in the 'Brocken spectre', an optical illusion caused by the refraction of sunlight through water vapour in the atmosphere.

Suddenly a vast shadow of a human form was seen projected on the cloud, surrounded by a prismatic halo of two concentric circles with streaks of light radiating upwards from the centre. As the mist receded and advanced the spectral shape enlarged and contracted, occasionally assuming proportions so gigantic and distinct as to be absolutely startling, and presenting a sublime and magnificent spectacle ... So vivid and terrifying indeed was the spectacle that the attendant servants were positively frightened and much inclined to bolt.26

The mountain, by enabling the bourgeois eye to 'rise above the World' and 'gratify' itself on 'one of the noblest prospects in the universe' and even cast its shadow on heaven, induced godlike feelings of 'superiority and command' which found spontaneous expression in the singing of hymns and 'God Save the King' on the summit.27 The ecstasy was further enhanced by the ventriloquism of the echo creating an illusion of the very mountain's fealty to god and king. Thus Semple compelled its 'wild solitudes . to re-echo the sacred name of God to the human voice', while Barrow and Lady Anne Barnard were moved to tears by the sound of the 'loyal mountains' echoing 'God save - God save God save - god save - god save - god save - god save - GREAT GEORGE OUR KING - great George our King - great George - great George - great George.'28

The eye at 'the centre of this great circle' could also attain 'a sort of unembodied feeling such as ... the Soul ... [might] have which mounts a beatified spirit leaving its atom of clay behind', being granted the power to see visions beyond the limits of the encircling horizon.29

In looking towards the mountains of Hottentot Holland, by means of that intellectual power which God has bestowed on man, we winged our way to their highest summits, and thence discovered with astonishment, in the innermost recesses of Africa, hordes of undiscovered and undescribed savages, prostrate before the light of new-born day. Beyond the waves of the Indian Ocean, the nations of Asia with their pagodas, their white-robed bramins, their inoffensive manners, and their antique superstitions. In the distant bosom of the southern ocean, we beheld clusters of peaceful islands, defended by reefs of coral, over which the waves slowly broke, and the friendly inhabitants asleep under the shade of their cocoa nut trees. With rapid thought we passed the shores of the Brazils and Spanish America, stained with innocent blood, and where the murmur of the waves upon the shore was mingled with the crack of the task-master's lash - the cries of the feeble Indian - and the noise of his mattock as he dug for gold. On the banks of the majestic rivers and lakes, and in the bosom of the forests of the western world, we beheld, with pardonable pride, English laws and institutions, English manners and men, firmly rooted; and pleased ourselves with the thought, that our language would thereby one day become the most extended that has perhaps ever been spoken upon the face of the globe. Then reverting towards the north, we lingered amidst the various cities, the polished arts, and the domineering policy of enlightened Europe; and fixing upon our own happy island, we forgot, for a short moment, all ideas of grandeur and sublimity, and melted at the recollection of the ties by which we felt connected with it.30

The bourgeois mind's eye, disembodied by the inhalation of the summit's 'aether' of the 'freest and purest air', was thus enabled to take in the full circumference of the earth and orientate itself within a wider imperial psychogeography along an emerging ley line of the Pax Britannica between England and its 'African capital'.31

If 'looking out' from the summit revealed an imaginary future beyond the horizon, 'looking down' offered a 'bird's eye view' of the present state of the colony and hence also a measure of the labour still required to realise the future perfect glimpsed by the bourgeois eye 'looking out'.32 The image most frequently evoked by 'looking down' - that of a plan, chart or map - was thus both descriptive and didactic; marking the faint road and boundary lines of the European presence in the landscape, but also the 'deserts' of unlined space still to be incorporated through 'cultivation' into the cartographic grid.33 The view of Cape Town itself generated a recurring companion metaphor to the map, that of a child's ephemeral efforts at urban design - 'the formal meanness of its appearance . lead us to suppose it built by children out of half a dozen packs of cards' - reflecting a fundamental and enduring English ambivalence about the oriental port they had inherited from the Dutch.34 The flat roof from the summit and stoep from the street provided the new Anglo elite with constant reminders of the decadence of their 'African capital' and its Dutch oligarchy, and prompted a preference for 'villas, châteaux and country retreats' on the eastern slopes of the mountain.35

The romantic mountain apprehended through the ocular imperialism of the sublime eye, remained as fraught with imaginary danger as the earlier wilderness, albeit no longer from wild beasts and runaway slaves. The old fear of physical attack was replaced by a new horror of no less lethal assaults on the senses by the summit itself. The 'giddy height' of the prospect exerted a powerful vertiginous attraction on its bourgeois beholders, Burchell reporting that 'a spectator cannot look down the awful depth directly beneath without feeling some dread, or giddiness: and some of our party could not, on that account, venture within several yards of the brink.'36 Half a century later an anonymous female spectator dared to look.

I peeped down cautiously over the dizzy precipice. This I must tell you is a rather hazardous undertaking, as the nerves of but few are strong enough to look down on the world below without growing faint and light-headed, with a yearning desire to throw oneself over. There was something so horribly fascinating in peering over the edge of this steep Cyclopian wall - looking down its rugged sides, and marking the jutting crags on which successively a body would fall in its downward flight, that you seemed powerless to restrain an almost irresistible longing to leap over, and dash yourself to pieces. Over five deaths are said to have been thus occasioned, as the results of imprudently placing confidence in one's strength of head; so I don't mind telling you, that I insisted on J- holding me by the ankle, as I stretched myself out on my knees and elbows, ere venturing to use my eyes.37

Thus, the same prospect that enabled the transcendence of the bourgeois eye 'looking out' into an all-seeing eye of god, simultaneously furnished it, when 'looking down', with a brutal reminder of its base mortality in the yawning maw of the void.38 The sudden and unexpected juxtaposition of immortality and mortality and the effort of repressing both the heresy and horror induced by the prospect produced an alarming disorientation in the bourgeois self.

The other danger of the summit had a more tangible cause in cloud, particularly the 'tablecloth' which enveloped it during a summer south-easter - a 'mist . so dense that it was impossible to distinguish any thing at the distance of a foot from us' and 'which hid us from each other and made everything loom up like ghosts around us' - but its effect was again most dramatic on the inner self.39The bourgeoisie never ascended the Mountain during a south-easter and when aloft were perpetually alert for any sign of the wind's onset in the form of 'suspicious looking clouds about the top of the mountain', as it was believed to be 'exceedingly dangerous to be caught with a S.E. wind on the mt. which causes its Table cloth to fall thickly upon it & thus presents an impenetrable barrier to the sight.'40 The cloud instantly inverted the panorama of the prospect by extinguishing all horizons and magnifying the immediate.

I know not whether you have ever been in situations to observe the strange effects of mist, in changing the forms of mountains, in giving vastness to the minute, in now concealing and now opening a partial and bewildering glimpse at the stupendous, until, often deceived, the wanderer loses all confidence in himself.41

Thus blinded, the once all-seeing bourgeois eye was condemned to imprisonment on the summit until the wind abated or, if insistent on trusting to its own perceptions, risked destruction in the void. The romantic mountain thus both reified an ocularly derived sense of self and revealed the eye as a treacherous and unreliable guide; the primary means of apprehending the sublime, but also easily and potentially fatally seduced by the precipice and disorientated by the cloud.

The recommended antidote to the dangerous instabilities of self induced by the undisciplined romantic gaze was to break it in the harness of reason, subordinating the fallible naked eye to the infallible mind's eye and sensations to science. The measurement and classification of the mountain, not the prospect, excited the scientific gaze and sent it aloft.42 Its first act was to disperse the myths that had enveloped the summit during the long eighteenth century. Thus ancient sea anchors, van der Stel's pillar and giant nocturnal crowned serpents yielded the mountaintop for want of empirical verification.43 The summit thus cleared, its 'real' dangers could be tamed through quantification and explication. The exact elevations of Table Mountain's 'immense wall' and the surrounding lesser summits, allowed them to be located on a continuum of known heights, from St Pauls to Monte Rosa and Mont Blanc, and revealed them to be modest at best.44 Similarly, the mystery of the tablecloth and Brocken spectre were rendered mundane by their translation into the physical laws governing the behaviour of light and water in a gaseous phase.

Science, however, was more than just a comfort for the inner terrors of romanticism, it was also the means for realising its dreams of an outer world transformed. The mind's eye would guide the spade in 'cultivating' the new empire of reason the British sought to inaugurate at the Cape.45 The utilitarian intent of the scientific gaze was evident right from the start, in Barrow's recommendations at the end of the eighteenth century for plantations and a canal on the mountain to alleviate the want of wood fuel and water constraining Cape Town's development.46And herein lay an irony; that in realising the romantic dream of desert transformed into garden, science would extend the cartographic grid lines of cultivation over the mountain itself, extinguishing the romantic prospect in the act of its pursuit. The contradiction was not immediately apparent owing to the amateur and ad hoc nature of both colonial science and administration, but rapidly became manifest in the final quarter of the nineteenth century as a gathering mineral revolution in the far interior spurred the systematic scientific 'cultivation' of the mountain by the state to produce timber and water for industrialisation and urbanisation on the peninsula.

The Summit, or the Mountain Domesticated

The only significant symbiosis between science and state at the Cape in the first half of the nineteenth century was the British navy's patronage of astronomy. An official observatory and astronomer were in place in Cape Town from 1828, at the foot of Devil's Peak.47 In addition to the routine labour of time-keeping and celestial observation in the service of improved maritime navigation, the resident astronomer was set the more esoteric task of measuring a meridian arc to settle a longstanding scholarly debate about the shape of the earth. To this end the incumbent, Thomas Maclear, and an army of assistants haunted the mountains of the south-western Cape for a decade from 1838 measuring a chain of 'primary triangulations' between Namaqualand and the Cape Peninsula.48 One link in this chain lay along the peninsula's mountain spine and in December 1844 Maclear, then ensconced on the heights at Cape Point, sent his assistant, William Mann, to the summit of Table Mountain in search of a site from which Cape Point, Robben Island and the observatory were simultaneously visible. This was only possible from a point well below the summit, so Maclear dispensed with a sightline on the observatory and ordered that 'a Pile' be built on the summit. A gang of twenty men under the direction of the observatory's carpenter laboured ten days breaking rock to erect a five metre high beacon coated with lamp black and grease.49

The beacon, a convenient but otherwise insignificant marker in the realisation of a grand enlightenment project, soon acquired practical local utility, turning the summit into a linchpin around which webs of private property could be spun across the surrounding landscape. Accurate survey was integral to the British reformation of the chaotic land tenure system inherited from the Dutch and made Maclear's Beacon a site of frequent professional pilgrimage for surveyors tying Cape Town into the geodetic network radiating out from its fixed point.50 Thus the grid lines of cultivation, which the romantics had fondly imagined stretching to the horizon from their vantage point atop the mountain a half century earlier, were realised and emanated quite literally from the summit. Although still invisible to the naked eye looking out, each boundary line fixed by the heliograph's transient wink was transcribed onto the survey map and rendered permanently visible to the official mind's eye.

Nor was the utilitarian reform impulse limited to tidying up the fictional landscapes of the map, but rather saw cartographic rectification as a precursor to the re-engineering of the natural and urban landscapes of the Cape peninsula itself, seeking to domesticate both through arboreal and hydraulic engineering. In the twenty years after 1884 the newly established Cape Forestry Department established plantations on the mountain at Tokai and Table Mountain (1884), (Devils) Peak (1893), East End (1895) and Cecilia (1902) containing nearly 10 million trees as part of an effort to ease the colony's dependence on imported timber.51 The summit had also been repeatedly surveyed with a view to urban water supply.52 Precise measurement was begun in 1881 when the first rain gauges and thermometers were permanently put in place.53 On the basis of this data the municipality of Cape Town built a tunnel through the mountain's western face to re-direct the flow of the Disa River from Hout Bay to Cape Town in 1891 and then double dammed it in the Woodhead (1897) and Hely Hutchinson (1904) reservoirs. These impounded 1,800 million litres of water to drive turbines lighting the town and end the annual summer triage of 'short allowance' endured by its citizenry.54

The foresters and engineers radically transformed the mountain environment firing, ploughing, scarifying, scoffeling, blasting and drowning thousands of hectares of 'wild bush' to impose the rational order of the arboreal grid and hydraulic wall on its uncultivated wilderness. By so doing, they also fundamentally altered the mountain's prospects, closing in some under the spreading plantation canopy and submerging others beneath the rising waters of the dam. The effect was most dramatically apparent at the intersection between leviathan's expanding arboreal and hydraulic estates on the mountain summit.

The 'caged seas' of the Woodhead Reservoir - its wall rearing forty-four metres up out of the stream bed - drowned sixty hectares of Disa Gorge and its successor - with a wall sixteen metres high - a further sixteen hectares, including the forestry department's Table Mountain plantation, which was first clear-felled, so that '[t]he most beautiful spot of Cape Town, and the first resort of all visitors, now ceases to exist.'55 Although reimbursed by the municipality for the cash value of the plantation, the conservator complained that 'this does not replace the beauty of this lovely valley, with its charm of clouds and crag and the flowing streams fringed with the brilliant Disa grandiflora.'56 The foresters conversely regarded their own sylvan engineering as enhancing the peninsula's natural beauty by clothing with trees 'the bleak and naked appearance of Table Mountain' and the 'bare and stony slopes above Woodstock and Salt River that have so long been a reproach and eyesore to Cape Town'.57

Forestry and hydraulic engineering, however, not only extinguished or altered mountain prospects, they also created them by 'opening up' the mountain through the ubiquitous construction of roads needed to realise their imperial designs. The Forestry Department built roads from Constantia Nek to the summit, Tokai to the railroad at Retreat, Devils Peak to Roeland Street and the Kloof Nek tramline, and Cecelia to Wynberg. Their plantations were also laid out on a grid of contour and zigzag cross-paths-cum-firebreaks, creating a wide range of new routes of access to and passage around the mountain. The Cape Town municipality further extended the system of 'fire paths' over Lion's Head and Signal Hill and along the mountain's western face beneath the Twelve Apostles. The municipal waterworks were similarly preceded by road making; a pipe track being laid to Kasteel's Poort for the original tunnel and an 'aerial ropeway' from there to the summit for the subsequent dams. W.C. Scully lamented that while in 1883 the mountain was 'as yet wild and untamed; one could still easily get lost among its many labyrinths', thirty years on 'it has been disfigured by houses, plantations, and reservoirs, and the cut pathways which score its once wild terraces always suggest to me cords binding a giant.'58 Although intended to enable the construction, superintendence and surveillance of leviathan's mountain estate, the steadily multiplying networks of major and minor roadways and their connections to public transport also encouraged popular entry to the mountain.

It was no coincidence that the Cape Town bourgeoisie first discovered the mountain in numbers in the 1880s. The alpine and the orchid crazes in Europe lent new lustre to Cape mountains and flora, but it was the path-making labour of the convict and 'Kafir' corvées raised by the colonial and municipal states that enabled local mountaineering and botany to flourish.59 The bridle path from Constantia Nek was 'daily traversed by horsemen' from its completion in 1884 and by the early 1890s '[m]any visitors now ride the entire distance.'60 The mountain's popularity as a picnic resort also boomed as the bourgeoisie sought out '[t]hat grand silence of nature, that far-from-the madding-crowd sort of enjoyment characteristic of a genuine Table Mountain picnic' on Sundays and public holidays.61 By the end of the South African War, it was estimated that 'nine-tenths of the able-bodied dwellers under the shadow of Table Mountain have at one time or another reached the mountain-top' and that 'thousands of persons come up from Cape Town' to the lower slopes on public holidays.62

The craze for indigenous flora, especially disas, provided another incentive for mountaineering. By the 1860s the Disa grandiflora was already 'the "Pride of Table Mountain" ... and many are the pilgrimages made to her shrine on the top of the mountain during the flowering season.'63 The fancy became increasingly commercialised, endangering the orchid and prompting the Forestry Department to introduce permits for flower collecting in 1889 to check 'the wanton destruction of the beautiful flora', but to no avail.64 'The demand for flowers, especially that of Disa grandiflora, has become almost a mania. So soon as a flower opens it is immediately secured by the professional flower gatherer, who scours the mountain at daybreak and leaves hardly a bloom behind.'65 The Table Mountain plantation, which straddled the Disa Stream, was thus closed to flower picking, fenced at either end and signposted, in a bid to make it 'possible for the ordinary visitors to study the beauties of the Disa in its natural home', before its inundation by the Hely Hutchinson reservoir.66

The middle class at play on the mountain imitated the public road making of the state. The 'Mountain Club' established in September 1891 - some wanted a 'Table Mountain Club' - boasted an impeccable bourgeois pedigree and ambitious program of road making; one of its first acts being the 'marking [of] a line across the summit of Table Mountain from Maclear's Beacon to the Poort (Platteklip Gorge), by painting a line of arrows at intervals.'67 Where this was not possible the path was beaconed with stone cairns and a concrete beacon erected at the head of Platteklip Gorge in 1892.68 As further aids to the safety of the bourgeois eye aloft, the club placed a three-handed signpost at Maclear's Beacon, a warning against descending Fountain Gorge, vetted the proliferating army of underclass 'guides' and then rendered them redundant by publishing the first pocket map of the summit and its main access routes in 1908.

Nor was the Club's mania for road-making confined to the mountain's horizontal planes. Within a decade the original 'four hum-drum routes up Table Mountain; viz., Platte-Klip Gorge, Kasteel Poort, Constantia Nek and the Bishopscourt route' had been increased elevenfold and thirty years later they numbered in excess of two hundred.69

The growth in middle class recreational mountaineering - the Mountain Club's membership jumped eightfold from 60 in 1891 to 490 by 1908 - increasingly challenged the forester's and engineer's utilitarian hegemony over the mountain, reasserting the primacy of sentiment and sensation over science.70 The engineers inadvertently created a new prospect with the erection of the aerial ropeway and found themselves besieged by the bourgeoisie eager to experience the novel eight minute frisson of the plunge into the void with the fear of death removed.71 The reservoirs also constituted a new view, which the middle class sought to appropriate for its recreational use as a picnic area and trout fishery. The municipality declined to indulge the demand for novel recreations by opening the aerial ropeway to joy riding or stocking the dams with trout, but its attempts to close the ancient rights of way over the summit catchment area met with strenuous opposition.

Having secured title to the summit, the relocation of the Forestry Department station and the destruction of its plantation to prevent pollution of the town water supply, the municipality saw no reason to kowtow to what its Medical Officer of Health derisively called 'sentimental objections of mountain wanderers'.72 In 1899, and again in 1904, it drafted regulations denying all unregulated public access to the summit catchment area (see Figure 1 above) on the grounds that this would contaminate the reservoirs and risk spreading a typhoid epidemic throughout the town. On both occasions sustained lobbying by the Mountain Club forced a compromise and official recognition of the bourgeoisie's demand that 'while they had pure water they should not be excluded from their right to enjoy pure air.'73In acknowledgement of the new modus vivendi, the municipality spared a house in the waterworks village from demolition in 1904 and granted it to the Mountain Club rent free as a Hütte.74

Conversely, the Forestry Department welcomed the public into its mountain plantations, arboreta and nurseries in a bid to foster popular arboriculture in the colony and endeavoured to accommodate the aesthetics of the bourgeois gaze. It maintained arboreta like 'urban parks', screened unsightly roads from view and planted them with quick grass to provide 'a pleasant walking surface', moved buildings from ridges to restore skylines and ultimately converted entire plantations into 'parks'.75 The department also constructed a bridle path from Kings Blockhouse to the tramline at Kloof Nek, ostensibly for fire protection, but actually to create a prospect of 'public resort'. 'The views obtained from this path are of unsurpassed beauty, and probably unique in the world, for within the limits of a short and easy walk the whole panorama of the City of Cape Town and its Suburbs, as far as Rondebosch, is exposed to view.'76

Despite pandering to the middle class, the foresters were increasing censured by it for their destruction of indigenous vegetation by plantations.77Bourgeois amateur botany became more sophisticated under the tutelage of its professional members and ardent in its defence of the indigenous through exposure to the depredations of engineers and foresters via recreational mountaineering.78Their identification with the indigenous was reflected in the Mountain Club's choice as its emblem of the orchid Disa grandiflora - 'the pride of Table Mountain' - over 'a cliché representing a view of Cape Town and Table Mountain from the bay ... more appropriate to a Table Bay Yacht Club.'79 Concern focused in particular on the silver tree (Leucadendron argenteum), a conspicuous endemic of Table Mountain which had long served as the indigenous counterpart to the European oak in local arboreal allegories of colonialism, and whose demise was illustrated in miniature on Wynberg Hill.80

There is a cruel, continuous, silent fighting on this hillside - the battle between the silver-trees and the firs. The firs, or pines, who came here last, are creeping year by year, higher and higher up the hill; year by year the brave little 'witteboomen' (white trees) are driven before this strong green army of invaders; soon there will be a last stand on the hilltop - the survival of the fittest. We shall all see it; we are seeing it every day of our lives - and will no one help81?

The conservator claimed that no effort was spared to preserve and replant this 'unremunerative tree' on the plantations, but the middle class remained sceptical and in 1909 secured the prohibition of its uprooting on public land, sale or export under the Wild Flowers Protection Acts82

Middle class activism not only blunted the utilitarianism of engineers and foresters, but also the montaine penny commerce of the urban underclass. Adherents of the 'King of Sports' had nothing but contempt for the underclass.83The traditional bete noir of the forester - the woodcutter-cum-incendiary - was now joined by a new folk devil, the flower picker, and the roadways closely watched by both official rangers and their self-appointed middle class auxiliaries for any signs of these 'unwelcome parasites' working a mountain commons redefined as the 'magnificent playground' of the bourgeoisie.84 Exclusion was reinforced by enclosure, wire fences barring all unofficial paths and channelling traffic onto the made roads policed by gates and rangers. Those sporting the solid silver 'Disa badge', however, were instantly recognisable to proprietors and public servants alike, as being 'of the right stamp' and their right of way unhindered.85

The bourgeoisie's appropriation of the domesticated mountain also had an ideological dimension, countering the utilitarian doctrine of economic efficiency with its own brand of christianised romanticism. The mountain was seen as a natural antidote to the unnatural world of Cape Town 'with its dull prosaic round of business life' and 'sedentary office-work' in the 'crowded nest of humanity'. 86 To those forced to 'do our work with a mountain at our elbow', 'the mountain seems perpetually to hold out a tacit invitation ... to come up into a purer air and forget for a time the trivial worries that wear out life.'87 In ascending to the summit both the 'buckram suited' St George's Street businessman and the 'round clerk in a square office' escaped 'the Town's defiling arms' and regained physical health through exercise and fresh air and mental health through contemplation of 'the wondrous earth-beauty, the landscape, the cloudscape, and all the sights and sounds of free nature.'88 Viewing could be empirical - the bourgeois eye acting as 'Scouts for the Philosophical Society' - or a spiritual reading of the mountain's many 'sermons in stones'.89 Adamastor, the pagan 'spirit of the mountain' flinched from Camoes, was now converted into a benign cathecist dutifully furnishing mountaineering pilgrims with trite allegories illustrating the first principles of their Christian creed.90

Finally, the urban middle class' increasing identification with and mystification of the mountain from the 1880s onwards also politicised it. Where the utilitarians claimed to be harnessing the mountain to serve the common good, the bourgeoisie unapologetically sought to remake it according to its own partisan preferences and prejudices, often in flagrant defiance or disregard of the common weal. This ultimately effected a re-orientation in prospect as profound as the reengineering of the mountain landscape undertaken by the foresters and engineers. Suburban village hostility to the metropolis meshed neatly with Anglo ethnic support for British imperialism to open a new prospect on the mountain's east face - looking away from the city and towards the interior. The resultant shift from north to east face made a militant middle class constituency available to pro-imperial politicians eager to take this prospect as their talisman and totem.

The East Face, or the Mountain Re-orientated

The view of Cape Town from the north face had long been an agony for the middle class. The aesthetic alarm that the town's flat-roofed houses evoked in early visitors endured throughout the nineteenth century, embellished by the resident's intimate knowledge of urban micro-geography. Thus 'Z' - in a dream a cloud 'watching Cape Town and its environs from my ever-welcome resting place, the grand Old Mountain' - reported:

It is rather to square (Cape Town I mean) to my eye for beauty ... certainly it has no points, at least no good ones, that I could see. The streets were muddy - we all know what that means, and how often their being so is the cause of regret that the pavements are so like the visits which are considered "few and far between". There was a gathering outside the Cathedral (fine building, would never tell a stranger what it was meant for) ... The metropolitan Railway station, with its sullen face, ever reminding the public that it felt how odious were comparisons between its suburban sisters and itself. Papendorp, that human pigsty, over which so many of our tears have fallen, but left it none the fairer or purer, and which those two gigantic reformers Christianity and Education alone have power to remedy. Then there were the pretty villages peeping out from their green hiding places. 91

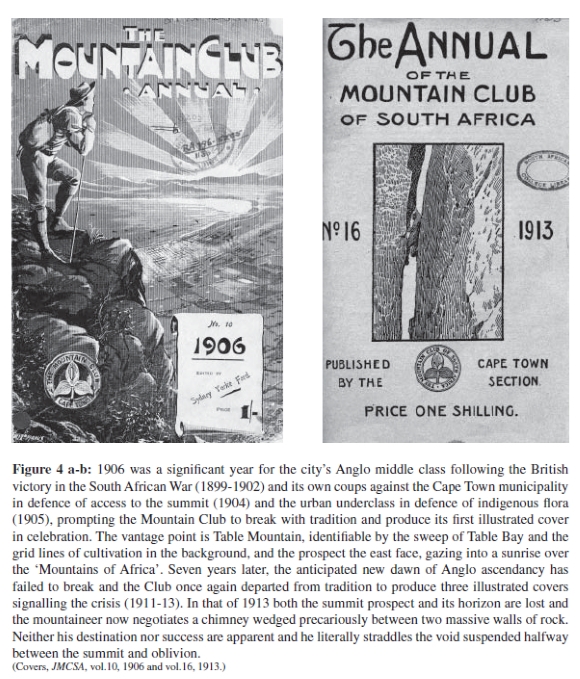

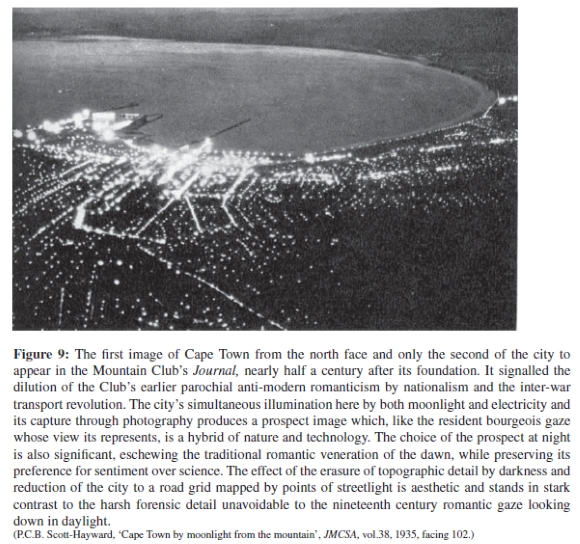

Such unsparing forensic inspection in the interests of urban reform was increasingly tempered by the middle class' failure to effect the desired changes and its compensatory resort to romantic anti-modernist pique.92 They thus rejected the north face in silhouette 'emblazoned on the badge of the Mountain Club ... as the symbol of their "order"' in 1895 and determinedly averted or displaced their gaze thereafter so as to efface the city completely from sight.93 Even the pleasure of the north face prospect at night was spoilt by the electrification of the city, which rendered it permanently visible from the summit.94

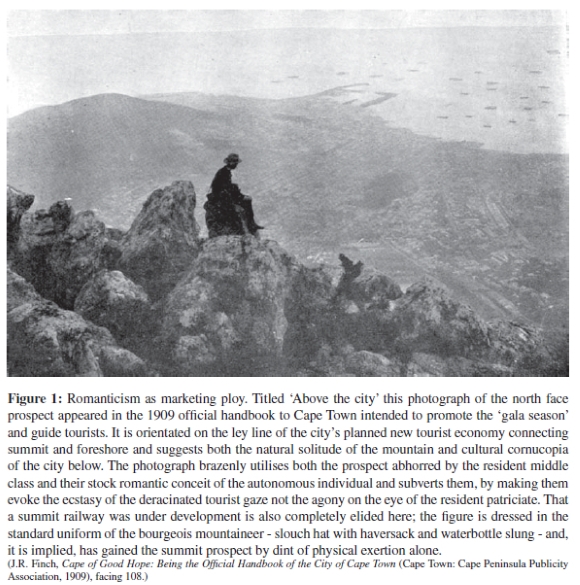

Two decades of public and private road-making directed at the summit also encouraged commodification of the historic prospect itself. The Cape Town muncipality sought to resuscitate the town's economy from a post-war depression in the mid-1900s by seconding nature to the service of tourism. To this end it inaugurated a 'gala season' in 1907 and took the lead in commercialising both the foreshore and summit by constructing a pier and railway via Platteklip Gorge with hotel accommodation on the summit as lures for tourists.95 The itinerant 'shank's pony' voyeurism of the resident middle class was thus to be replaced with mechanised mass viewing of the summit prospect by paying tourists.96

(J.R. Finch, Cape of Good Hope: Being the Official Handbook of the City of Cape Town (Cape Town: Cape Peninsula Publicity Association, 1909), facing 108.)

The 'pride of Table Mountain' feared the city transplanted to the summit; 'As far as the eye can see, tourists armed with glasses, peppermints, motor veils, etc., viewing the land' to the ringing cry of '"Ahgas! Speshul, Ahgus!"'.97

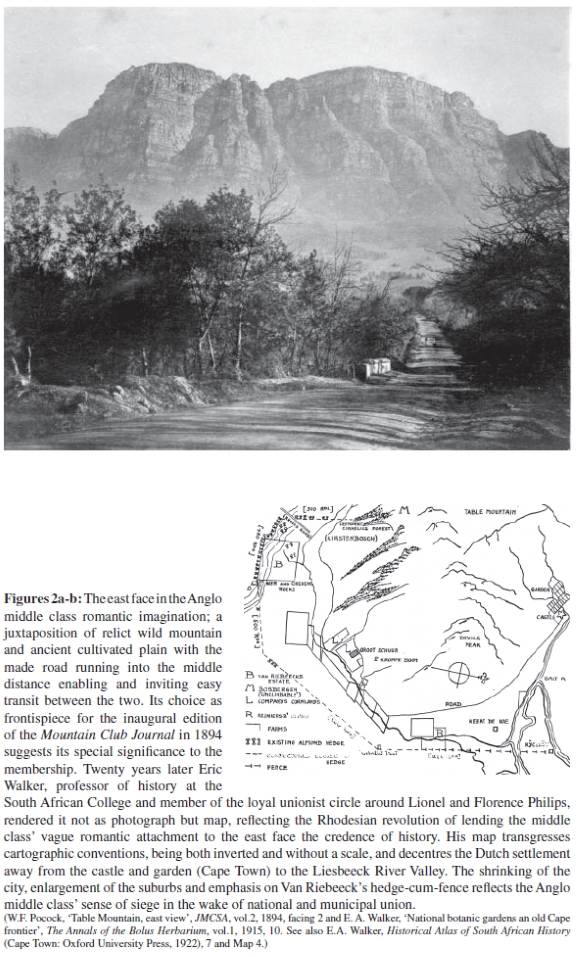

The vulgarity of the city and its determined 'vulgarisation of the summits' inclined the resident middle class to look increasingly east to the 'garden of the Cape'.98 They were drawn to a prospect where the bourgeois eye looking down beheld European colonialism's primal scene in Africa (the first cultivation of the soil by a settler yeomanry) and, looking out, its manifest destiny (a white man's land from Cape to Cairo).99 The middle class had been relocating to the suburban villages erected on the first farms of the Dutch free burghers in growing numbers since the 1860s as the line of rail advanced down the mountain's eastern flank. There they imagined they had found both a rural antidote to the city and a remnant of the mountain sublime.

Although not as 'striking and extra-ordinary' as the north face, the east face, being better watered, was deemed 'undoubtedly the most beautiful and picturesque'.100 'Indeed this side of the mountain never has the parched aspect which characterises the Northern and Western declivities in mid-summer. The grey rocks are always more or less framed and laced with greenery, the deep cool ravines are rarely devastated by fire, and it must be a phenomenally dry summer when the streams within them have entirely ceased to flow.'101 After winter rains the streams were 'converted into raging mountain torrents', and

those who have counted the pleasure of seeing Nature in her wildest moods greater than the bodily discomfort which is entailed in penetrating into these fastnesses at such a time, say that they have seen no grander sights than are to be seen during the rainy season in these ravines. It is as if sluice gates had been raised at the heads of the gorges and the pent-up waters of a mighty reservoir suddenly released. The water rushes down the precipitous portion of the mountain with irresistible force, carrying trees and rocks with it in its headlong career.102

The 'magnificent gorges, which cleave so deep into the mountain that the sun cannot penetrate into their innermost recesses' also harboured trees 'of great antiquity . dwarfed in height and gnarled and twisted in the quaintest fashion, but . [with] boles of enormous thickness.'103

The East Face as Imperial-cum-National symbol

Although driven by purely local considerations, the sentimental reorientation of the Anglo middle class to the east face coincided with and exerted a powerful shaping influence on an emerging settler imperial nationalism in the colony. As a result Table Mountain came to loom large in the philosophies of the two indigenous champions of the imperial connection, Rhodes and Smuts, and, like a Brocken spectre, cast a long shadow over South African politics down the twentieth century.

When Rhodes became prime minister of the Cape in 1890 he followed the resident middle class' lead in seeking, on the slopes of the east face at Rondebosch, a residence appropriate to his status. After purchasing the old DEIC warehouse at Groote Schuur in 1893, he further followed form by obsessively laying out roads to create prospects and clearing the horizons of all constructions detracting from the romantic illusion of a mountain wild.104 He also imbibed the local veneration for the 'spirit of the mountain', taking to daily rides and hours of solitary contemplation on the slopes and extolling its mystical enhancement of thought. Rhodes' means merely enabled him to indulge the resident bourgeoisie's mountain romaticism on a grand scale, ultimately investing £60,000 in assembling a 3,700 hectare estate on the mountainside between Devils Peak and Wynberg Hill.105

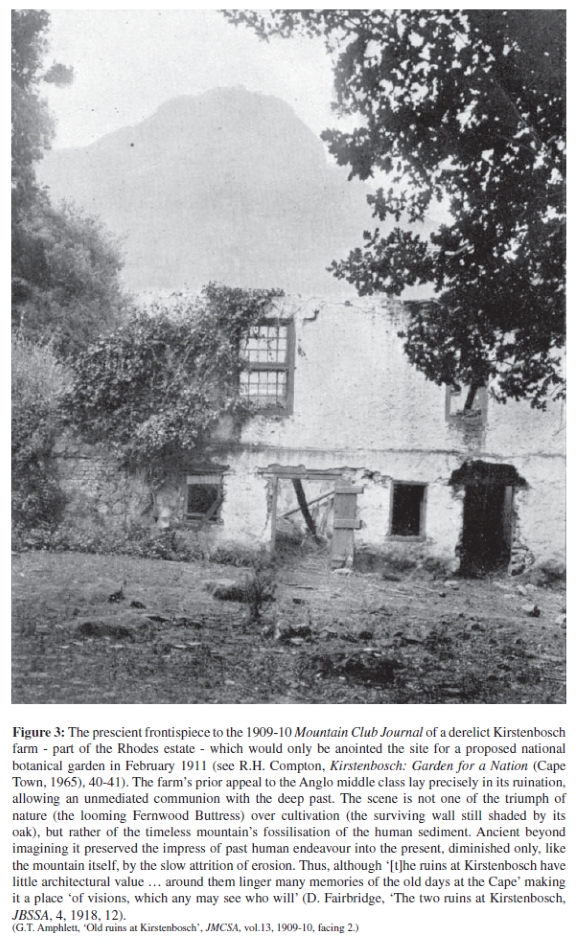

Rhodes, however, was both innovator and imitator of the resident middle class's nascent east face tradition, his novel contribution being to lend it historical depth by rooting it in a Dutch foundation. This dressing of Anglo imperialism in the DEIC drag of a vernacular architecture and fostering of a Van Riebeeck cult was driven primarily by the desire to cement an ill-starred political alliance with the Afrikaner Bond.106 It also resonated with an Anglo urban middle class disabused of the biblical fictions about the age of the earth and origin of their own species, who held the mountain to be a product of Neptunian sedimentation over aeons and regarded its 'postdeluvian ruins' as a massive memento mori 'which Time and Age defy'.107 Just as Table Mountain fossilised the vast abyss of geological time, so too it was now seen to have preserved the scrim of human history deposited upon its slopes by 'the original inhabitants of the soil' against the erosion of time.108Table Mountain had both 'witnessed' the founding act of European settlement -'the small vessels, after braving the terrors of the unknown, flutter like frightened birds into the bay' - and preserved the fortifications, farms and even boundaries made by the first settlers upon its east face.109 Recognising the mountain as a mausoleum of European settlement, Rhodes' impulse was restorative, that of his bourgeois acolytes contemplative.110 The Anglo middle class was now able to read the mountain as either spiritual or historical allegory and in both instances with the same message - 'Excelsior'.

Rhodes provided the Anglo middle class with a genealogy and heritage with which to stake a claim to belonging in the face of increasingly hostile challenges from emergent Afrikaner and African nationalisms.111 The spirited defence of Dutch gables and governors, alongside Table Mountain and indigenous flora, thus became unambiguous markers of class and ethnic identity.112

In gratitude, they accorded Rhodes full civic honours and subscribed liberally to his memorialisation upon his death in 1902.113 The admiration was mutual, for, although his body was buried in the Motopos Hills, his Table Mountain estate was designated the site of his memorial. To this end the estate was bequeathed to a future unified South Africa with Groote Schuur as the official residence for its prime ministers.114 The memorial was intended to provide an indelible imperial impress on both the east face prospect and the new nation state, but in such a way as to suggest its indigeneity - a classical temple hewn from Table Mountain sandstone.115 From there Rhodes, become the 'spirit of the mountain', would keep eternal watch over both the east face and the new South African nation and, by turning his favourite prospect into a site of pilgrimage, commune with future generations who had come to share his view, his message of 'whole-hearted and ungrudging service to South Africa, to the Empire, and to Humanity.'116

Rhodes' Ozymandian ambitions barely survived him and in the decade between his death and the public unveiling of his memorial in July 1912, the east face's centre of gravity began shifting south, away from the imperial memorial towards a new 'national' precinct at Kirstenbosch.117 This dramatic realignment in east face's psychogeography was triggered by the crisis in Anglo middle class hegemony and identity caused, first by their merger into a national union under the Republican generals in 1910, and then into municipal union with the city of Cape Town in 1913.

Stripped of their political power and imperial identity, the Cape Town patriciate floundered. Their attempt in 1910 to win national government support for a new 'national' botanical garden failed because of a glib insistence that it be located in Cape Town and more particularly on Rhodes' estate at Groote Schuur.118The opening of the adjacent memorial by Rhodes' friend and ex-Governor-General of Canada, Earl Grey, in 1912 further tainted the scheme in republican eyes and only its strategic relocation to Kirstenboch at the opposite end of the estate enabled it to garner a grudging and parsimonious government endorsement in 1913.119Even then, the first director, H.H.W. Pearson, planned a Rhodesian style palladian memorial at the heart of Kirstenbosch to Lord de Villiers, Rhodes acolyte and patron of the garden, giving the new site an unmistakable imperial imprimatur, a scheme apparently only aborted by Pearson's untimely death in 1916.120 The patriciate's concomitant attempt to thwart the Cape Town municipality's planned summit railway revealed them to have been similarly marginalised by union in their own backyard. Having forced the issue to a vote, they suffered a resounding and humiliating defeat at the poll in 1913 and construction was only finally averted by the outbreak of war the following year.121

These defeats forced the Anglo middle class to reinvent itself and cloak the east face in national rather than imperial garb after 1910. They were long accustomed to think of themselves as inhabiting an 'island' apart from the continental 'mainland', with the mountain's shadow on the isthmus - 'a long intensely blue line stretching from one ocean to the other' - as natural 'boundary-line' betokening 'safety and shade within its depth, war and barbarians beyond'.122 The middle class now belatedly sought to bridge the isthmus to 'the awe-inspiring piled-up barrier of the great continent to the North'.123 The Mountain Club, which earlier claimed the stock imperial interest in 'every peak from here to the Pyramids', now struck a more modest and conciliatory national pose changing its name to the 'Mountain Club of South Africa' in 1911 and claiming to have effected Union in miniature by uniting the 'two races ... for a common object, free from racial animosity or inglorious strife'.124 The middle class made further symbolic connections with the mainland by tying their island from its eastern prospect to the 'stone men' on the summits of the 'blue mountains' etching the interior horizon - 'from left to right, from the Great Winterhoek to little Hangklip trailing down to the sea' - in imitation of the colonial astronomer-surveyors.125

The ultimate price of national belonging, however, was paid by the Anglo middle class in blood during the Great War. Some ninety-one members of the Mountain Club alone served and nine perished.126 This blood sacrifice in defence of the new nation-in-imperio was duly commemorated by a memorial adjacent to Maclear's Beacon, fortuitously incorporated into Kirstenbosch in 1922 through the cession of the 'Upper Kirstenbosch Nature Reserve' by the Union Forestry Department.127

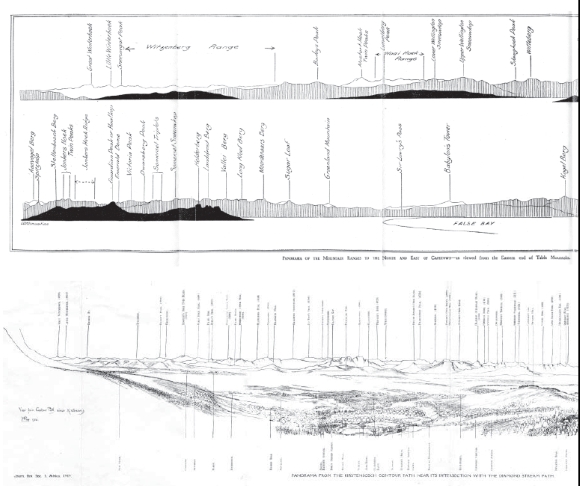

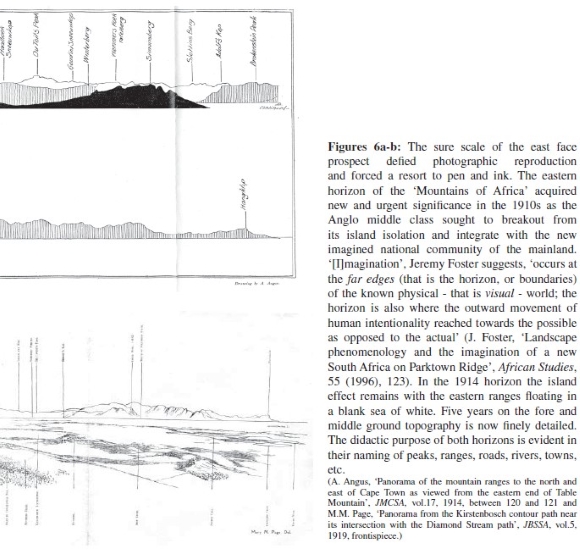

(A. Angus, 'Panorama of the mountain ranges to the north and east of Cape Town as viewed from the eastern end of Table Mountain', JMCSA, vol.17, 1914, between 120 and 121 and M.M. Page, 'Panorama from the Kirstenbosch contour path near its intersection with the Diamond Stream path', JBSSA, vol.5, 1919, frontispiece.)

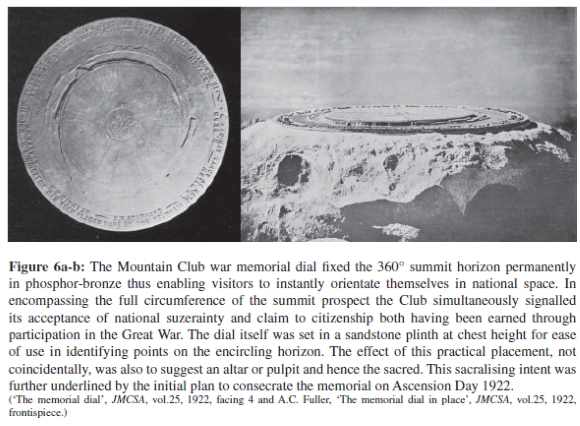

The memorial dial, cast by the Salt River railway works mechanical engineer's department, fixed the 360° horizon permanently in bronze bas relief. Briefly displayed in the window of the Union Castle Company's Adderley Street office, the 30 kilogram dial was carried to the summit via Kasteels Poort and the Club hut and mounted on a natural sandstone pedestal prepared by a stonecutter in May 1922. Its dedication was delayed for nearly a year, however, first by a violent storm on Ascension Day 1922 and then the unavailability of the new prime minister, Jan Smuts, to officiate.128

In Smuts, the Anglo middle class found an indigenous reincarnation of Rhodes who espoused their own particular brand of imperial nationalism. A Cambridge educated Afrikaner from the Swartland, Smuts advocated an aggressively expansionist 'Greater South Africa' under British aegis after Union.129That he was also a dedicated mountaineer and accomplished botanist only served to confirm him as one of their own. There was thus no one more fitting to induct the 'pride of Table Mountain's' dead into the national Valhalla, one site of which would forever be at the summit of the east face. Smuts' contribution to the tradition was to elevate the middle class' mountain romanticism into a universal philosophy. Where Rhodes innovated by deed, Smuts did by word.130 More than two thousand people ascended on 23 February 1923 to hear him consecrate the summit as a cathedral to the new 'Religion of the Mountain' in an address instantly hyperbolised as ranking with that of Demosthenes to the dead of Chalonia, Pericles in Thucydides and Lincoln at Gettysburg.131

What is that religion? When we reach the mountain's summits we leave behind us all the things that weigh heavily down below on our body and our spirit. We leave behind all sense of weakness and depression; we feel a new freedom, a great exhilaration, an exaltation of the body no less than of the spirit. We feel a great joy. The religion of the Mountain is in reality the religion of joy, of the release of the soul from the things that weigh it down and fill it with a sense of weariness, sorrow and defeat. The religion of joy realises the freedom of the soul, the soul's kinship to the great creative spirit, and its dominance over all the things of sense.132

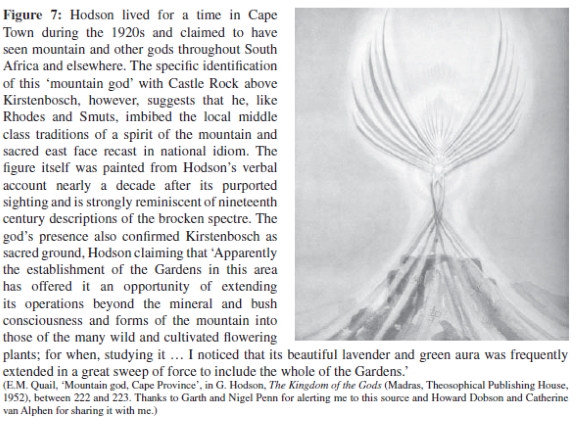

Smuts spoke the language of his Anglo middle class audience in invoking the 'spirit of the mountain' they themselves had long recognised and revered on the summit. Freed from its Christian strait-jacket, the Brocken spirit enjoyed a revival as pantheist essence in the 1920s, in Smuts' own magnum opus, Holism and Evolution (1926), and the more obscure, but no less mystical, writings of the theosophist Geoffrey Hodson (1921-29).133

For the agnostic majority, the memorial created a new sight line on the east face - from botanical garden to summit memorial - in an emerging civic religion of settler nationalism and on the now annual pilgrimage each February the numbers of the faithful were always massively inflated by Smuts' attendance.

A decade on from the annus horribilis of 1913, the Anglo middle class had extricated itself from the abyss and regained the horizon. But, just as in the wake of the South African War, its triumph proved transient. The following year Smuts fell from power to wander the political wilderness for a decade and in 1925 the Cape Town City Council revived plans to construct a means of public transport to the summit, this time of a cable- rather than a railway.

Smuts continued to assiduously court the Anglo middle class constituency after 1923 and pay regular obeisance at its shrines, walking on the mountain whenever he was in Cape Town and regularly attending the annual Mountain Club memorial services and gatherings of Botanical Society members at Kirstenbosch.134 They in turn claimed a unique intimacy with the private Smuts - 'the simple man of the Mountain, with the mountain's own character' - forged on the mountain:

We feel that we can perhaps claim a closer affinity with Smuts than any of those who knew him as statesman, philosopher, soldier and scientists. It was on the Mountain that he could put aside all those multifarious activities and reveal to himself and to us the human Smuts; simple, vigorous, full of the zest of physical action and personal achievement, glorying in the sunlight and the free air, carefree for the moment, enjoying the climb and the arrival at the summit as we do ourselves.135

His presence on the east face attained a talismanic quality for the Anglo middle class, which went to great lengths to retain it, the city council presenting Smuts with a retirement cottage in the Kirstenbosch garden in 1949.136 With his death in September 1950 he, like Rhodes before him, was transformed into the 'spirit of the mountain'. 'Smuts has gone, but the Mountain remains for us and those who come after us. Long may we guard it, and long may his spirit live among us.'137 He was memorialised in the same vein in the east face Valhalla via a bronze plaque set in the rock face below the summit beacon, which lauded him in the words of Shakespeare's eulogy to Brutus:

His life was gentle and the Elements

So mixt in him that Nature might stand

And say to all the world; This was a man.138

A Return to the North Face, or the Mountains of Modernism

No successor emerged to don Smuts' Rhodesian mantle and the new Afrikaner nationalist government was able to wrest both the Dutch legacy and mountain away from its self-appointed Anglo curators and re-locate their public shrines and prospects back to the north face. They were helped in this by a steady secularisation of the mountain during the inter-war period through increased public access.

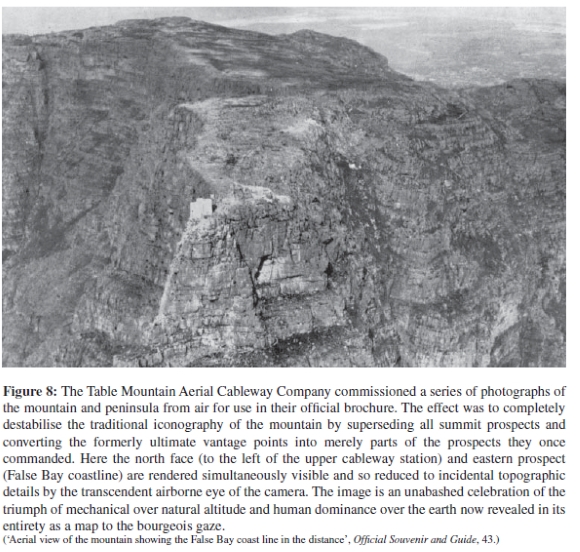

The opening of a road around Chapman's Peak in 1922 completed the construction of a marine drive encircling the peninsula mountain massif. The city council sought to complement this with a similarly easy ascent to maximise its return from the growing number of foreign and South African middle class tourists to the city.139 Although the steamship and railway remained their main means of travel to and round the city, the conversion of the mountain into a tourist attraction was also driven by the anticipated growth in mass tourism from the rise in private automobile ownership and commercial airplane travel. The prime mover behind the cableway was the chairman of the South African Automobile Association and its financiers Rand mining capitalists including Ernest Oppenheimer.140 Construction began in 1927 and the first paying passengers made the ascent in 1929, a year after a Baby Austin took four hours to reach the summit in a publicity stunt.141

Anglo middle class opposition was less strident and more resigned than in 1913.142 This was partly due to generational change and the opening of the Club to a national membership, but mainly reflected a fundamental transformation in the middle class' own view of the mountain under the influence of the post-war transport revolution. The automobile opened up a vast new weekend pleasure hinterland in the interior for the Cape Town bourgeoisie and 'motorneering' made them less dependent on Table Mountain.143 The aeroplane also superseded the summit as the ultimate prospect available to the bourgeois eye, reducing all natural vantage points finally to mere details in the panorama par excellence of the world made map.144

The middle class, in short, was seduced by the massively expanded scope of voyeurism enabled by modernism's photographic memory, annihilation of distance by time and defiance of gravity. Their new mechanically enhanced gaze, with its camera and combustion engine prosthetics, almost trivialised the mountain and its anti-modern romanticism. The summit eclipsed, its spirit dissipated and the totemic power of the east face for the Anglo middle class was gradually displaced back to the north prospect from where the city's nightly son et lumiere of modernity was revealed to the bourgeois eye aloft.

* Thanks to Andrew Bank for infinite patience, close reading and considered comment and the flowers. Also to Neil Lessem, Brendan Manning, Larry Musnick, Nigel Penn, Andrew Duncan Smith and Megan Voss for sharing sources and ideas.

1 See for example W. Cronon, 'The trouble with wilderness; or, getting back to the wrong nature', in W. Cronon, Uncommon Ground: Rethinking the Human Place in Nature (New York: W.W. Norton, 1996), 69-90 and E. Kaufman, 'Naturalizing the nation: the rise of naturalistic nationalism in the United States and Canada', Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol.40, 1998, 666-95.

2 See for example M-L. Pratt, Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation (London: Routledge, 1992).

3 See for example D. Bunn, 'Comparative barbarism: game reserves, sugar plantations and the modernisation of South African landscape' in K. Darian-Smith et al (eds), Text, Theory and Space: Land, Literature and History in South Africa and Australia (London: Routledge, 1996), 37-52; C. Rassool and L. Witz, ''South Africa: a world in one country: moments in international tourist encounters with wildlife, the primitive and the modern', Cahiers d'etudes africaines, 143, 1996, 335-371; D. Bunn, 'An unnatural state: tourism, water and wildlife photography in the early Kruger national Park', in W. Beinart and J McGregor (eds.), Social History and African Environments (Oxford: James Currey, 2003), 199-220 and J. Foster, '"Land of contrasts" or "home we have always known"?: the SAR&H and the imaginary geography of white South African nationhood, 1910-1930', Journal of Southern African Studies, vol.29, 2003, 657-80.

4 F. Cooper, 'The dialectics of decolonisation: nationalism and labour movements in postwar French Africa' in F. Cooper and A.L. Stoler (eds.) Tensions of Empire (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 406-435.

5 See W. Beinart, 'South African environmental history in the African context' in S. Dovers , R. Edgecombe and B. Guest (eds.), South Africa's Environmental History: Cases and Comparisons (Cape Town: David Philip, 2002), 222-26 and P. Merrington 'Heritage, letters and public history: Dorothea Fairbridge and Loyal Unionist cultural initiatives in South Africa, c.1890-1930' (Ph.D thesis, University of Cape Town, 2002).

6 See for example S.E.G. Fuller, 'Continuity and change in the cultural landscape of Table Mountain' (MSc Environmental and Geographical Sciences, University of Cape Town, 1999); N. Vergunst, Hoerikwaggo: Images of Table Mountain (Cape Town: South African Nastional Gallery, 2000); J. Dubow, 'Rites of passage: travel and the materiality of vision at the Cape of Good Hope' in B. Bender and M. Winer (eds.), Contested Landscapes: Movement, Exile and Place (Oxford: Berg, 2001), 241-45 and T. Goetze, 'Table Mountain: South Africa's natural national monument', Historia, vol.47, 2002, 457-78..

7 See H. Wittenberg, 'Rhodes Memorial: imperial aesthetics and the politics of prospect', Centre for African Studies Africa Seminar, University of Cape Town, 20 March 1996 and compare with J. Pickles, 'Images of landscape in South Africa with particular reference to landscape appreciation and preferences in the Natal Drakensberg', (Ph.D thesis, University of Natal, 1978).

8 P. Kolb, The Present State of the Cape of Good Hope (New York: Johnson Reprint Corporation, 1968), 3.

9 See V.A. Seeman, 'Forts and fortifications of the Cape Peninsula 1781-1829' (MSc Archaeology thesis, University of Cape Town, 1993) and D. Sleigh, The Forts of the Liesbeeck Frontier (Cape Town: Castle Military Museum, 1996).

10 F. Le Vaillant, New Travels in the Interior Parts of Africa, 1783-1785, Volume 1 (London: G.G. and J. Robinson, 1796), 120.

11 Le Vaillant, New Travels, vol.1, 108 and 119-20.

12 See for example Le Vaillant, New Travels, vol.1, 119-20; A. Sparrman, A Voyage to the Cape of Good Hope, 1772-1776, Volume 1 (London: G.G. and J. Robinson, 1785), 72-73 and A.M. Lewin Robinson (ed.), The Cape Journals of Lady Anne Barnard, 1797-1798 (Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society, 1994), 221.

13 Compare R. Ross, Cape of Torments Slavery and Resistance in South Africa (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1983), 19-20 and 54-72 with the Crusoe fiction of Joshua Penny taken for fact in W.H. Crump, 'A cavern which secured me from storms', Journal of the Mountain Club of South Africa [JMCSA], vol.61, 1958, 25-29 and J. Penny, The Life and Adventures of Joshua Penny (Cape Town South African Library, 1982), 30-36.

14 O. Mentzel, A Geographical and Topographical Description of the Cape of Good Hope, Volume 1 (Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society, 1921), 90.

15 Mentzel, Geographical and Topographical, 90.

16 J. Barrow, An Account of Travels into the Interior of Southern Africa, 1797-1798, Volume 1 (New York: Johnson Reprint Corporation, 1968), 20. See also W. J. Burchell, Travels into the Interior of South Africa, Volume 1 (Cape Town: Struik, 1967), 32.

17 A.M. Lewin Robinson (ed.), The Letters of Lady Anne Barnard, 1793-1803 (Cape Town: Balkema, 1973), 46.

18 See M.H. Nicolson, Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory: The Development of the Aesthetics of the Infinite (Cornell: Cornell University Press, 1959) and S. Schama, Landscape and Memory (London: Harper Collins, 1995).

19 R. Semple, Walks and Sketches at the Cape of Good Hope (Cape Town: Balkema, 1968), 73 and 82 and Mentzel, Geographical and Topographical, 88.

20 Lewin Robinson, Letters, 49 for the quote and Semple, Walks and Sketches, 82; A Lady, 'life at the Cape: letter IV', Cape Monthly Magazine, vol.1, November 1870, 264 (reprinted as Life at the Cape a Hundred Years Ago, by a Lady (Cape Town: Struik 1963)) and W.H. Crump, 'Samuel Haydon, JMCSA, vol.61, 1958, 58-59 for graffiti.

21 See M. Voss, 'Wilderness domesticated: nineteenth century perceptions of Table Mountain', Historical Approaches, vol.1, 2003, 39-48 for a preliminary exploration.

22 Burchell, Travels, vol.1, 33 and C. Abel, Narrative of a Journey in the Interior of China (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme and Brown, 1818), 287.

23 The quotes are from Barrow, Travels, vol.1, 37 and Lewin Robinson, Cape Journals, 218. See also Le Vaillant, New Travels, vol.1, 106 for another instance of the dual motives of curiosity and science in seeking out the summit and Lewin Robinson, Cape Journals, 221-22 and B. and N. Warner (eds.), The Journal of Lady Jane Franklin at the Cape of Good Hope, November 1836: Keeping up the Character (Cape Town: Friends of the South African Library, 1985) 56-57 for faux science.

24 Barrow, Travels, vol.1, 37 and Semple, Walks and Sketches, 74 for the description of Platteklip Gorge.

25 Lewin Robinson, Letters of Lady Anne, 49.

26 'The "Brocken spectre" on Table Mountain', Cape Monthly Magazine, vol.1, 1870, 383. Thanks to Gregor Leigh for the physics.

27 The quotes are from Lewin Robinson, Cape Journals, 220; Le Vaillant, New Travels, vol.1, 112; Semple, Walks and Sketches, 82; R. Percival, An Account of the Cape of Good Hope (London: Baldwin, 1804) 127 and Burchell, Travels, vol.1, 37.

28 Semple, Walks and Sketches, 81and Lewin Robinson, Letters, 49.

29 The quotes are from Semple, Walks and Sketches, 79 and Lewin Robinson, Cape Journals, 221.

30 Semple, Walks and Sketches, 79-80.

31 The quotes are from Lewin Robinson, Cape Journals, 221; Burchell, Travels, vol.1, 37 and G. Thompson, Travels and Adventures in Southern Africa, Volume 1 (Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society, 1967), 47.

32 See for example Lewin Robinson, Letters, 49 and Warners, Lady Jane Franklin, 58 for "birds eye view".

33 See Barrow, Travels, vol.1, 38; Burchell, Travels, vol.1, 36; J.W. Grill, J.F. Victorinos Travels in the Cape1853-1858 (Cape Town: Struik, 1968), 7; B. and N. Warner (eds.), Maclear and Herschel: Letters and Diaries at the Cape of Good Hope 1834-1838 (Cape Town: Balkema, 1984), 63; J. Ewart, James Ewart's Journal (Cape Town: Struik, 1970), 53-54 for the ubiquitous cartographic metaphor.

34 See Lewin Robinson, Letters, 49 for the quote and K. MacKenzie, ' The South African Commercial Advertiser and the making of middle class identity in early nineteenth century Cape Town' (MA Thesis, University of Cape Town, 1993) for initial Anglo efforts to reform Cape Town.

35 Lady, 'Life at the Cape', 264.

36 B. Warner (ed.), Lady Herschel: Lettersfrom the Cape, 1834-1838 (Cape Town: Friends of the South African Library, 1991), 138 and Burchell, Travels, vol.1, 35.

37 Lady, 'Life at the Cape', 262.

38 See P. Gay (ed.), The Freud Reader (London: Vintage, 1995) 612-23 and 773-83. Thanks to Anastasia Maw for discussion and references on this point.

39 The quotes are from Le Vaillant, New Travels, vol.1, 111 and Lady, 'Life at the Cape', 267.

40 C.F. Bunbury, Journal of a Residence at the Cape of Good Hope (London: Murray, 1848), 75 and Warners, Diary of Lady Jane Franklin, 38.

41 C. Rose, Four Years in Southern Africa, (London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, 1829), 38.

42 C.P. Thunberg, Travels at the Cape of Good Hope, 1772-1775 (Cape Town, Van Riebeeck Society, 1986), 114-17 and 144 is the classic example of the rational enquirer who made fifteen ascents in three years with hardly any mention of the summit prospect at all.

43 See Barrow, Travels, vol.2, 80 for the anchor; Le Vaillant, New Travels,vol.1, 116 for van der Stel's pillar; Kolbe, Present State, 13 for the serpent and 'Brocken spectre'.

44 Percival, An Account, 131 for St Pauls and Lady, 'Life at the Cape', 262 for Monte Rosa and Mont Blanc.

45 See for example N. Penn, "Mapping the Cape: John Barrow and the first British occupation of the colony, 1795-1803", Pretexts, vol.4, 1993, 20-43; J.C. Weaver, 'Exploitation by design: the dismal science, land reform and the Cape Boers, 1805-22', Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, vol.29, 2001, 1-32 and E. Green Musselman 'Swords into ploughshares: John Herschel's progressive view of astronomical and imperial governance', British Journal for the History of Science, vol.31, 1998, 419-35.

46 See Barrow, Travels, vol.1, 19; J. Barrow, An Autobiographical Memoir (London: J. Murray, 1847), 215-16 and Penn, 'Mapping the Cape'.

47 See P. Moore and P. Collins, The Astronomy of Southern Africa (London: Hale, 1977) 44-70 and B. Warner, Astronomers at the Royal Observatory Cape of Good Hope (Cape Town: Balkema, 1979)

48 See G. Everest, On the Triangulation of the Cape of Good Hope (London: Extract from the Memoirs of the Astronomical Society, 1823) for the need and T. Maclear, Verification and Extension of La Caille's Arc of Meridian at the Cape of Good Hope (London: Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, 1866) for the result.

49 From K.H. Barnard, 'William Mann. Astronomer - mountaineer', JMCSA, vol.46, 1944, 15 and 19-21 and B. Warner, 'Maclear's beacon Table Mountain', JMCSA, vol.81, 1978, 24-25.

50 See Weaver, 'Exploitation by design'.

51 Calculated from Cape of Good Hope, Reports of the Conservator of Forests, 1884-1904. See also G.L. Shaughnessy, 'Historical ecology of alien woody plants in the vicinity of Cape Town, South Africa' (Ph.D thesis, University of Cape Town, 1986).

52 See for example Cape of Good Hope, Report of the Hydraulic Engineer, 1881 [G20-82], Appendix A, 12-19 and 'Notes and notices', JMCSA, vol.27, 1924, 108-9.

53 C. Ray Woods, 'The meteorology of Table Mountain', JMCSA, vol.2, 1895, 35-36.

54 See D. Grant, 'The politics of water supply: the history of Cape Town's water supply, 1840-1920' (MA thesis, University of Cape Town, 1991) for the best available account and Cape Town City Council [CTCC], Mayor's Minute, 1894, 22 for the quote.

55 R. Juta, The Cape Peninsula (Cape Town: Juta, 1910), 81 and Cape of Good Hope, Report of the Conservator of Forests, 1899 [G24-1900], 14. Also 'Additional storage reservoir, Table Mountain', JMCSA, vol.5, 1899, 18-19 and F.E. Mills, 'Early days', JMCSA, vol.55, 1952, 4.

56 Report of the Conservator of Forests, 1899, 14.

57 Cape of Good Hope, Report of the Conservator of Forests, 1882 [G105-83], 17 and Cape of Good Hope, Report of the Conservator of Forests, 1892 [G27-93], 17.

58 W.C. Scully, Further Reminiscences of a South African Pioneer (London: Fisher Unwin, 1913), 155.

59 See D.D. Zink, 'The beauty of the Alps: a study of the Victorian mountain aesthetic', (Ph.D thesis, University of Colorado, 1962) and P.H. Hansen, 'British mountaineering, 1850-1914' (Ph.D thesis, Harvard University, 1991) for imperial alpinism and F.E., 'A scramble in the Uitenhage Alps', Cape Monthly Magazine, vol.36(61), June 1873, 339-44 and H. Bolus, 'The orchids of the Cape Peninsula', Transactions of the South African Philosophical Society, vol.5(1), 1888, 1-200 for local manifestations of alpinism and orchiphilia..

60 Cape of Good Hope, Report of the Conservator of Forest, 1884 [G32-85], 7 and Cape of Good Hope, Report of the Conservator of Forests, 1891 [G23-92], 84.

61 E.E. Cadby, 'Up Table Mountain in the aerial gear', Cape Illustrated Magazine, vol.7, 1896, 375.

62 "Lady climbers of Table Mountain', JMCSA, vol.8, 1903, 13 and Cape of Good Hope, Report of the Conservator of Forests, 1903 [G26*-1904], 27.

63 J. McGibon, 'The botany of Table Mountain', JMCSA, vol.15, 1912, 150.

64 Bolus, 'Orchids', 148 and Cape of Good Hope, Report of the Conservator of Forests, 1889 [G36-90], 61.

65 Report of the Conservator of Forests, 1891, 84.

66 Report of the Conservator of Forests, 1891, 84.

67 G.T. Amphlett, 'A trip to the Cedarberg', Cape Illustrated Magazine', vol.7, 1896, 65 and 'The Mountain Club, its origin, and doings during the first two years', JMCSA, vol.1, 1894, 8.

68 Mills, 'Early days', 3-4.

69 The quote is from C. Amphlett, 'prosperity of the Mountain Club', JMCSA, vol.8, 1903, 9. See also A.S. Rogers, 'Climbing the face of Table Mountain', JMCSA, vol.1, 1894, 42-44 and 'The climbs on Table Mountain: a classified list of routes', JMCSA, vol.34, 1931, 94-119.

70 Graph of Mountain Club membership, etc, 1891-1941, JMCSA, vol.42, 1941, facing 68.

71 See Cadby, 'Up Table Mountain'; 'The aerial ropeway Table Mountain', JMCSA, vol.4, 1898, 21and Juta, Cape Peninsula, 78-91.

72 CTCC, Mayor's Minute, 1898, 72.

73 'Annual dinner', JMCSA, vol.5, 1899, 14. Also 'Table Mountain catchment area', JMCSA, vol.9, 1904-05, 37-39.

74 'The club house on Table Mountain', JMCSA, vol.9, 1904-05, 44 and 'The club hut', JMCSA, vol.10, 1906, 50.

75 The quotes are from Cape of Good Hope, Report of the Conservator of Forests, 1893 [G50-94], 9; Cape of Good Hope, Report of the Conservator of Forests, 1897 [G29-98], 16 and Cape of Good Hope, Report of the Conservator of Forests, 1894 [G51-95], 23. Rhodes paid the department to remove a tool shed, 'considered to be out of harmony with the beautiful scenery of its surroundings', from the ridge below Kings Blockhouse.

76 Cape of Good Hope, Report of the Conservator of Forests, 1905 [G50-1906], 26 and Cape of Good Hope, Report of the Conservator of Forests, 1903 [G26-1904], 27.

77 See 'Tree planting in South Africa', JMCSA, vol.3, 1896, 26 and D.E. Hutchins, 'Tree planting for mountaineers', JMCSA, vol.10, 1906, 14-18 for the only two published attempts by foresters to recruit Club members to their cause

78 P. MacOwan, 'Montum divitiae: findings and keepings', JMCSA, vol.1, 1894, 12-26 and Mills, 'Early days', 4.

79 K.H. Barnard, 'The Club badge', JMCSA, vol.44, 1941, 72-3.

80 Lewin Robinson, Letters, 44.

81 Juta, Cape Peninsula, 62-3. Also R. Juta, The Masque of the Silver Trees (Cape Town: Juta, n.d.).

82 Report of the Conservator of Forests, 1903 , 3 and Cape of Good Hope Government Gazette, no.9156, 23 March 1909, Proclamation 137, Clause 6.

83 Amphlett, 'Prosperity', 10.

84 A. Handel-Harmer, 'On prowling alone', JMCSA, vol.15, 1912, 131 and 'Lady climbers', 15 for the quotes. Also Juta, Cape Peninsula, 78-79 and L. van Sittert, 'From mere weeds and bosjes to a Cape floral kingdom: the re-imagining of indigenous flora at the Cape c.1890-1939', Kronos, 28, 2002, 102-26 for flower pickers and 'Annual dinner', JMCSA, vol.5, 1899, 13 and 'The Mountain Club's annual dinner', JMCSA, vol.14, 1911, 83 for "playground".

85 A.C.W. Bean, 'Among the clouds at the club hut', JMCSA, vol.11, 1907, 50 and 'Mountain Club's annual dinner', 82.

86 A.C.W. Bean, 'Our Easter "camp" at Smitswinkel', JMCSA, vol.10, 1906, 56; P. MacOwan, 'Montium divitiae', 12 and F.C. Kolbe, 'Side-lights on mountain-climbing', JMCSA, vol.2, 1895, 24.

87 A. Handel-Harmer, 'My first rock climb', JMCSA, vol.14, 1911, 86 and 'Lady climbers', 13.

88 MacOwan, 'Montium divitiae', 13; R., 'A round clerk in a square office', JMCSA, vol.42, 1939, 29; A. Vine Hall, Table Mountain: Pictures with Pen and Camera (Cape Town: ?, ?), ? and C. Amphlett, 'Prosperity to the Mountain Club', JMCSA, vol.8, 1903, 10.