Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

Kronos

On-line version ISSN 2309-9585

Print version ISSN 0259-0190

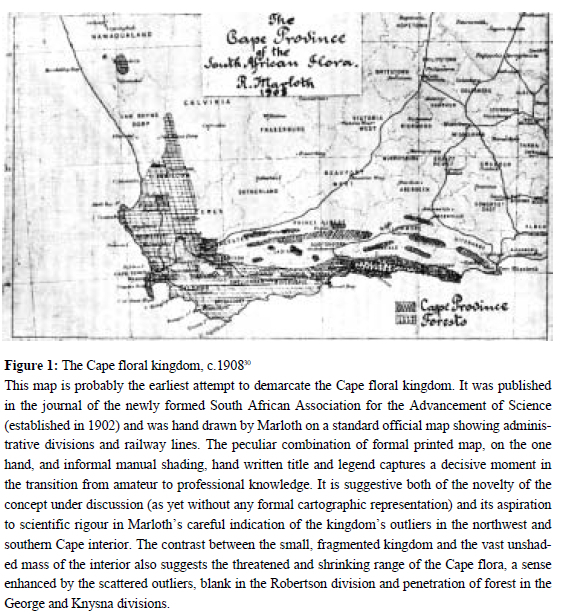

Kronos vol.28 n.1 Cape Town 2002

From "mere weeds" and "bosjes" to a Cape floral kingdom: the re-imagining of indigenous flora at the Cape, c.1890-1939*

Lance Van Sittert

University of Cape Town

"The Elegant Tribe of Heaths"

When the young botanist William Burchell rambled on Table Mountain in 1810, he recognised "[i]n the bushes, weeds and herbage by the road-side, at every step ... some well-known flower which I had seen nursed with great care in the greenhouses of England." Burchell found that "[m]any beautiful flowers, well known in the choicer collections in England, grow wild on this mountain, as the heath and the primrose on the commons and sunny banks of our own country."1 "Cape flora" had been "quite the rage" in Europe for some time: from the last quarter of the eighteenth century onwards

The conservatories, temperate houses, and gardens of England and the continent teemed with the Pelargoniums, Heaths, Proteas and handsome flowering shrubs, and the lovely bulbous plants of Irideae, Amaryllideae and Liliaceae; and the pages of the Botanical Magazine and other similar periodicals were filled with figures and descriptions of them.2

Observing the domesticated exotics of the metropole in their natural surrounds at the height of European mania for "Cape flora" filled Burchell with such rapture that he likened the entire Peninsula to "a botanic garden, neglected and left to grow to a state of nature."3 He was amazed to discover that Cape Town's elite were utterly indifferent to the "botanical riches" that surrounded them:

It may naturally be supposed, that, in a country abounding with the most beautiful flowers and plants, the gardens of the inhabitants contain a great number of its choicest productions; but such is the perverse nature of man's judgement, that whatever is distant, scarce and difficult to be obtained, is always preferred to that which is within his reach, and is abundant, or may be procured with ease, however beautiful it may be. The common garden-flowers of Europe are here highly valued; and those who wished to show me their taste in horticulture, felt a pride in exhibiting carnations, hollyhocks, balsamines, tulips and hyacinths; while they viewed all the elegant productions of their hills as mere weeds. It is not uncommon in the gardens at Rondebosch, to see myrtle-hedges twenty feet high ... but in none are any of the elegant tribe of heaths ever seen under cultivation; and it is a curious fact, that, among the colonists, these have not even a name, but, when spoken of, are indiscriminately called bosjes (bushes).4)

It was ironic that Burchell himself in quest of the exotic should admonish the inhabitants of Cape Town for this pursuit.

A preference for the exotic over the indigenous was a hallmark of botanical tastes in all settler colonies. Crosby argues that settlers preferred a "portmanteau biota" of more or less domesticated European plants and animals to indigenous flora and fauna.5 The indigenous people, flora and fauna were feared and despised in equal measure until after the closing of the frontier and first stirrings of settler nationalism when the now subjugated (and hence domesticated) indigenous was belatedly appropriated as wilderness and totem.6

The Cape Colony, however, did not entirely conform to Crosby's model in that the sliver of temperate zone in the southwest corner of the African continent was too small to enable the creation of a dominant "neo-Europe" along the lines of North American or Australasian colonies. Instead the creolised south-western Cape became an anachronistic appendage to a much larger region in which indigenous peoples greatly outnumbered settlers and the European cultural portmanteau was africanised. In this context an awakening to and identification with indigenous flora became a badge of regional rather than national identity. Its "discovery" was also made by and largely for an urban, English-speaking middle class - the underclasses and the countryside retaining their historical floral eclecticism.

This shift in colonial urban middle-class botanical tastes and sensibilities is best apprehended through a series of "soundings" in the discourse of the indigenous that emerged over the half-century after 1890. This discourse informed the evolution of both professional and popular botany in the southwestern Cape, differentiating the former from its imperial progenitor and marking out the latter as an imperial rump within the new settler nation state founded in 1910. The discourse of the indigenous was thus simultaneously an ideology of settler nationalism and ethnicity. Janus-faced it marked out both the new white nationalism from its imperial past and the Cape English liberal tradition from its northern republican adversaries, simultaneously cementing and fragmenting the new imagined community of "South African" settler nationalism.

A Mania for the Exotic

The Cape middle class' penchant for the exotic was displayed in the public and private gardens they created during the course of the nineteenth century. Private botanical gardens established at Bantry Bay (1804), Kloof Street (1829) and Claremont (1845) were all devoted to exotics and their official successor, established in 1848 on the site of the old Dutch East India Company garden in the centre of Cape Town, continued the practice.7 Indeed, the new public botanic garden was stocked from the more than 1,600 exotics in the Kloof Street garden and superintended by, among others, Ralph Henry Arderne, proprietor of the private Jardin d'acclimatation in Claremont.8 The exotic ousted the indigenous to such an extent that when the botanist Gamble visited Cape Town in 1890, he reported:

I was in hopes, when I visited the Garden of finding a named collection of Cape heaths, the Proteas, the Geraniums, the Gladioli and the other chief constituents of the beautiful and most interesting "bush" or "veldt" vegetation; but the Gardens had not even a single silver-tree to show a stranger, and the heaths, and indeed all flowering plants, were conspicuous by their absence.9

The antipathy of middle class subscribers towards "African plants" was so strong that the director dared not plant any, knowing that: "The public would have taken the alarm at once. They care nothing for the special prehistoric flora of the land they live in, compared with the newest hideous abortion in chrysan-themums."10 Consequently, the garden remained, in the view of botanists, nothing more than "a lounge or pleasaunce of idle hours for the population living close by."11

Suburbanisation sparked a private gardening boom, which the perenially cash-strapped botanic garden was forced to supply. It soon encountered stiff competition from private nurserymen, the director complaining in 1882 that "Sales diminish as one clever gardener after another quits the employ and starts a business for himself."12 By 1906 there were no fewer than 90 nurseries on the Cape Peninsula - more than half the total in the colony.13 Nurserymen had to specialise to survive, but in "fruit trees (especially citrus trees), Roses, Palms, Table Plants, and a few florist lines, there is a standing demand which always justifies practical labour, and allows reasonable prices to come in."14

After 1882 the Forestry Department also began selling exotic saplings and seed to the public from its plantations at Tokai and Uitvlugt. A host of quick-growing exotics were made available at cost and competitions organised to reward the most zealous arboreal converts.15 More than a million exotic transplants (over three-quarters Australian myrtle and sweet hakea) and nearly nine tons of seed (two-thirds Port Jackson willow) were distributed between 1882 and 1900 alone, so that by 1911 some 5,700 hectares of the Peninsula was under private plantation.16 Dorothea Fairbridge, journeying by train to the spring flower show in Tulbagh in the early 1920s, passed through "miles of Wattle-covered land ... utterly destructive to the native flora" and denounced the "utilitarians" of the Forestry Department and their ambition of "some day seeing the Cape Flats green with cabbages."17

Cape Town began to export its "mania for the exotic" to the interior. By 1877 it was said of the Cape Town botanic garden:

There is hardly a village or district on this side of the Orange River, and even beyond, which has not by its agency been supplied with imported trees, shrubs and flowering plants and the finest varieties of fruits, grapevines, mulberries, grass and clover, and other valuable productions of different kinds have thus been introduced and spread over the country to its incalculable benefit.18

The Cape Department of Agriculture, established in 1888 fifteen years after Responsible Government, gave added impetus to the spread of the exotic into the countryside. Its monthly journal proselytised for imported fodder and crop plants and won willing converts, particularly among "progressive" farmers in the eastern pastoral districts where there was mounting concern about the deterioration of pastures due to overgrazing.19

Never for example, was such a forage plant destined to restore the fallen condition of the struggling flock-master as Prickly Comfrey, now gone and abandoned like many other things ill adapted and useless to our general requirements. Then a shade tree boomed upon novelty-seekers was that wonderful one that was to supersede anything like it before known in this colony, the "Bel Sombra" or "Belhambra", as it was first called by someone probably fresh from the befogged atmosphere of Leicester Square. Later on there came with a rush the much-belauded leguminous shrub, "Tagasaste", a splendid fodder for stock in the Canary Islands where they have nothing better to eat. Finally, passing by lesser aspirants to popular favour, we were favoured with trumpetings of the special virtues belonging to "Wagner's Flat Pea".20

By the mid-1890s, however, misgivings began to be expressed about the "pernicious 'booming' of [exotic] plants", the Colonial Botanist recognising that "the indigenous herbage is better suited to the conditions of the climate than a great many of the exotics which have been introduced and recommended for cultivation in many parts of the Cape Colony."21 This was an expression of a new discourse on the indigenous flora, which claimed for it a unique and threatened status requiring urgent legislative action to prevent its imminent extinction.

The Elite Amateur Origins of Colonial Botany

"Cape Botany" had been a metropolitan science since the seventeenth century, patronised by European royalty and practised by their scientists on the gleanings of professional collectors, expatriate officials and dilettante settlers in the colony.22 Attempts to introduce scientific botany in the colony itself fell foul of the Cape insistence on "practical science".23 The Cape Town Botanical Garden was run by a succession of artisan gardeners for the first three decades of its existence and under the botanist belatedly appointed in 1881 was still compelled to "peddle roses and fuschias and six-penny worths of seeds to eke out its maintenance."24 Similarly, the post of Colonial Botanist and associated Chair in Botany at the South African College were summarily scrapped in 1866 (after only eight years) following the premature death of the first incumbent, Ludwig Pappe, and widespread popular disenchantment with the second, John Croumbie Brown.25

The absence of institutionalised botany allowed wealthy amateurs to try their hands and two new arrivals in Cape Town, a stockbroker from Graaff-Reinet, Harry Bolus (1876), and an analytical chemist from Germany, Rudolf Marloth (1883), became the leading practitioners and reshaped the discipline in the region.26 Long residence and extensive travel in the colony gave their work a very different preoccupation to that of the European compilers of great taxonomic inventories of Cape flora.27 Although Bolus and Marloth were active participants in the latter, they were particularly concerned with "plant-geography", the division of the subcontinent into "floristic" regions on the basis of plant dis-tribution.28 They substantially revised and expanded the earlier work in this field to reveal

the great difference which exists between the South Western corner of the Cape and the other portions of the country, the typical Cape flora being confined to the narrow sickle-shaped strip between the coast and the mountain ranges which form the Western and Southern boundaries of the Karoo, viz., the Cedarbergen and the Zwartebergen.29

Cape flora was now being proclaimed not only different to that of the rest of southern Africa, but globally unique in its great richness of species and "extreme antiquity."30 Earlier speculation that the Cape was an ice-age refuge for European flora was discredited by comparative work, which revealed the absence of European species and striking similarities between Cape flora and those of temperate regions of Australia and South America, all deemed "relic floras" of an ancient southern super-continent.31 The south-western Cape was now declared "a living museum, like some oceanic island".32

Extinction was implicit in the notions of uniqueness and antiquity attached by the colonial botanists to the flora of the south-west. Bolus had been sanguine about any threat in 1886. He recorded that although there were 158 species of "foreign vegetation" in the region:

Few of the introduced plants are found far from roadsides or human habitations, and it is remarkable how small upon the whole is the influence they exert upon the aspect of the vegetation, and how weak . is their aggressive power as against the indigenous Flora.33

This notion of the Cape flora's robustness was short-lived. Only ten years later, Peter MacOwan, the director of the Cape Town Botanical Garden, called for the creation of refuges for the "living memorials of the prehistoric past before they give out under conditions of man's occupation and become extinct", noting that "this risk is far from fanciful. There are plants whose whole known area is limited to a few score square yards."35 Bolus himself, writing in 1905, now reflected that:

[F]ew botanists who ... have spent many years in South Africa, and especially in the south-western districts, have not been penetrated by a gloomy impression that the South-western Flora is dying out, and is doomed to extinction . Many species collected by Thunberg, Masson and Burchell have never, or but very rarely, been seen since. Some of the finest Ericae have disappeared, often doubt-less destroyed by bush-fires; and in general species of the Bruniacaea, Proteacaea and Penaesceae, so peculiar to this Region, seem to have become much more rare.37

These new botanical sensibilities were communicated initially through the forums and journal of the South African Philosophical Society, formed in 1877 and patronised by Cape Town's middle class, with Bolus, Marloth and MacOwan all serving terms as office-bearers.38 Marloth also played a central role in the formation of the Mountain Club in 1891, which articulated a strong and consistent preservationist discourse.39

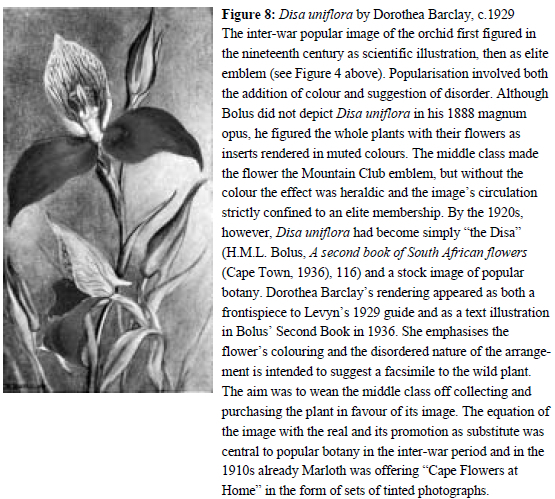

With the opening of the Botanical Garden to the public, on Sundays from 1875 and throughout the week from 1890, Cape Town's middle class turned increasingly to Table Mountain for its recreation. The domestication of the mountain was facilitated by the establishment of government plantations in the early 1880s with the concomitant appointment of rangers and the laying of paths. The club's membership rose from sixty in 1891 to more than 400 by the end of the decade. It chose the indigenous orchid, Pride of Table Mountain (Disa uniflora), as its emblem. Satellite clubs were formed at Worcester, Stellenbosch and Wellington and in 1893 the mother club made its first excursion by rail to the Matroosberg at Worcester.40 This became an annual event, which exposed Cape Town members to the flora of the city's rural hinterland.

Cape botany was freed from its historical dependence on the fickleness of the public purse and middle class fashion by Harry Bolus' £1,000 endowment for a Chair of Botany at the South African College in 1902.41 Henry Harold Welch Pearson arrived in Cape Town the following year via Cambridge, Peradinya (the famous imperial botanical garden in Ceylon) and Kew, as the colony's first full-time Professor of Botany. Cape Town's claim to be "the natural and rightful capital" of the Cape floral kingdom was confirmed by its retention of the colony's key public and private herbaria.42 The colonial botanist's herbarium was inherited by the South African Museum when MacOwan retired in 1905 and the post was once again abolished.43 Bolus left his herbarium, library and private residence to the South African College upon his death in 1911, along with £27,000 to provide for their upkeep and another £21,000 for scholarships for needy students.44

Defending the Indigenous: Colonial Botany and the Wild Flower Trade

The gradual indigenisation and institutionalisation of botany at the Cape and mobilisation of a middle class constituency enabled local botanists to mould official policy in accordance with their notion of a unique but endangered regional flora. This was evident in their sustained attempts to suppress a burgeoning wild flower trade.

Indigenous flowers first appeared regularly for sale in Cape Town stores and streets from the mid-1880s. By the end of the century Adderley Street flower sellers had become such a familiar feature of the urban landscape that they were a stock subject for postcards.45

Dependent on harvesting flowers free from the commons to turn a profit, the wild flower trade was dominated, in the middle class imagination at least, by women and children, but as the image above shows men were also employed.49In addition to the local market, Cape flowers were also sent by rail to Johannesburg and by steamship abroad. Some 70 tonnes of fresh flowers and 1,000 tonnes of everlastings (Helichrysum spp.) were exported overseas during the 1890s.50 This burgeoning commerce denuded the Cape Peninsula. The Forestry Department introduced permits for gathering flowers on Table Mountain in 1893 and prohibited the practice entirely after 1897, but the railway enabled collectors to go further afield. The magistrate of Simonstown, for example, complained that

many persons other than mere pleasure-seekers are in the habit of coming into this district for the purpose of picking wild flowers and heaths and carrying them away for sale elsewhere . These persons may be not inaptly described as Locusts or, Voetgangers, for nothing is spared by them and rare flowers are taken away roots and all.51

The wild flower trade prompted pessimistic prognoses about the future of the Cape flora and colonial botanists began to intervene politically. At the foundation meeting of the South African National Society in February 1905, Pearson called for "a scheme whereby the wholesale gathering of wild flowers and plants for the purpose of public sale and exhibition be checked or at least regulated."52 A committee that included Bolus, was formed to take the matter further and an audience with the Attorney-General was granted within the week. Draft legislation was referred to the committee for comment the following month and the botanists - "those who ought to know" in one member's telling phrase -were a powerful invisible presence in the House of Assembly throughout the debate on the Wild Flowers Protection Bill in May 1905.53 Although criticised by some for oppressing farmers and the poor , the Bill passed on a rising tide of nascent national sentiment expressed through a fetishisation of the colony's "natural beauty."54 This sentiment was assiduously cultivated by the National Society, so that when the "experts" asked the House to further regulate the wild flower trade in 1908, the amending legislation was waved through with hardly a murmur of dissent.55

The Wild Flower Protection Acts sought to prevent the harvesting, sale and export of flowers, plants, bulbs and roots of indigenous species deemed in danger of "extermination".56 Some species could be traded under annual licence, however, and all indigenous flora on private land, cultivated in gardens, exhibited and sold at "agricultural, horticultural and other shows or exhibitions" and collected for a "scientific (botanical) purpose" were explicitly excluded from its provisions.57 The various aspects of the nascent middle class culture of indigenous flora - commerce, gardening, exhibitions and science - were thus left undisturbed, while underclass participation was summarily outlawed or reduced through the Act's curtailing of their harvesting public land.

The legislation's effectiveness, however, was more apparent than real. As the list of prohibited plants was extended and refined, it required an increasingly sophisticated botanical knowledge to obey or enforce the regulations, knowledge beyond flower sellers, consumers and policemen.58 The difficulties of enforcing the Wild Flower Protection Act alerted colonial botanists to the need for cultivating a more popular audience than the discipline had hitherto been willing to address.

The Rise of Popular Botany

The incorporation of the former Cape Colony into the Union of South Africa in 1910 created a dilemma for Cape botany. The locus of political power shifted away from English Cape Town to the Afrikaans north nationally and to the countryside provincially. No longer able to presume either an intimacy of knowledge or automatic loyalty from their new rulers, the Cape botanists attempted to reinvent themselves as settler nationalists. They endeavoured to solicit patronage from Pretoria by cloaking their imperial empathies and preoccupations in the "practical science" of economic botany, but their promise of cash crops from the Cape flora to assist in national economic development, was half-hearted and wholly unconvincing.59 It backfired because the Cape botanists were unable to deliver on the promise and, by making it, antagonised the new national Department of Agriculture, which resented the infringement on its perceived domain. National government hostility was confirmed by the creation of a National Herbarium at Pretoria in 1923 and the parsimonious government allowance granted to Cape botany throughout the inter-war period.60 The failure to garner national support created an enduring fear of annexation by the centre and forced Cape botany to seek allies both closer to home and further afield.

It sunk its roots still deeper into the soil of urban, English Cape Town, while assiduously cultivating the affections of the British public and the imperial botanical establishment abroad.61 By 1928 more than half of the Botanical Society's members lived on the Cape Peninsula and its foreign membership accounted for another 14%, more than that of the three other provinces combined.62 Cape botany's strongly English-imperial flavour precluded it from attracting Afrikaner support.63 While the Oxbridge Afrikaner Smuts was venerated and feted at every opportunity, there were no more than token gestures towards the broader Afrikaans-speaking public, and Cape Afrikaner nationalism founded a rival volk's plantekunde at Stellenbosch in 1921.64 Thus, although Cape botany professed a national character throughout the inter-war period, it did so with more complaint than conviction, for it remained, in truth, a profoundly colonial discipline dominated by Cape Town's elite and the systematic project of its imperial progenitor. This could not endure indefinitely and isolation from the centre lent added urgency to the creation of a wider popular audience in the interests of protecting both the discipline and Cape flora from extinction.

The idea of a national botanic garden was first publicly mooted by a botanist in the employ of the old colonial Department of Agriculture, N.S. Pillans, in June 1910, followed by H.H.W.Pearson's better known presidential address to the South African Association for the Advancement of Science in November.65 Pearson proposed an African Peradinya and further showed his imperial preferences by arguing that Cape Town was the only suitable location for the envisaged "State Garden" with the "historic ground" of Rhodes' Groote Schuur Estate the natural site. Although such partisan pleading failed to garner an official response, Pearson's proposal continued to circulate among Cape Town's middle class where the idea of a state garden at Groote Schuur was revised to become that of a university garden at Kirstenbosch.66 This was the proposal championed by the city council in an audience with the prime minister in 1912 and put by Lionel Philips, a leading light of the National Society, to Parliament in May 1913 in a speech written for him by Pearson.67 The Prime Minister, in his other role as Minister of Agriculture, grudgingly agreed to provide the land and £1,000 per annum towards the upkeep of the garden, provided its trustees found the rest.68 "Kirstenbosch", Pearson's successor would complain, "has been persistently regarded as a little local institution, fit only to live on local charity."69 The Botanical Society of South Africa was immediately launched in Cape Town to rally the middle class to the standard of Cape botany.

Pearson's primary aim was to make Kirstenbosch a centre for the preservation of Cape flora, but, as the failure of the Wild Flower Protection Acts showed, this required the diligent cultivation of both public sensibility and plants. "The public taste must be stimulated to a proper appreciation of the aesthetic value of one of the most striking of the products of the country, and our duty as custodians of a unique vegetation - many of whose constituents have already disappeared, and others can with difficulty be saved - must be realised."70The civilising effect of education was a central tenet of nineteenth century Cape liberalism and the colonial botanists were firm believers in the "great . educative value of the study of the native vegetation of the country."71 Without such education, it was feared that "[t]he Kaffir and Hottentot traditions and beliefs, with those of illiterate Europeans, are handed down and accepted as facts."72

Kirstenbosch replaced the old Cape Town Botanic Garden in the affections of the urban middle class. It possessed the unique virtue of being simultaneously on their private doorsteps and removed from easy popular access by public transport. Botanical Society membership grew steadily from the original 214 in 1913, topping 1,000 by 1928 and nearing 2,000 by 1939. Subscriptions contributed more than £16,000 to the garden's upkeep over the quarter century after 1913.74 The main attraction for those paying their £2.2s as family, £1.1s as ordinary and 5s as associate members was not science, but the offer of free seed and propagation advice. Kirstenbosch sparked "a great awakening of interest in the cultivation of our native plants" and by the mid-1930s the demand was threatening to overwhelm its nursery staff.75 In deference to members' interests, the society's journal emphasised the popular botany of gardening over the scientific variant.76 "Little Kirstenbosches" sprang up through Cape Town's southern suburbs and were as creole in their make-up as their namesake.77

Edith Struben, artist and life member of the Botanical Society, was one ardent disciple. At "Luncarty" on the slopes of Table Mountain she aimed to "win back . some of the pristine glory of its native flora which in many parts is being slowly choked out of existence by foreign interlopers, such as pines, gums, etc."78 To this end the property was cleared of pines and from the regenerated indigenous flora "only weeds and unsightly plants removed, everything else being left or planted as nearly as can be done on nature's plan and in suitable surrounds."79 This "natural" "South African . garden" co-existed with an inner garden, exotic in both its design and content:

The more formal garden near the house, as it should appear part of the design of the "Home", has terraced lawns, clipped hedges with formal trees, pergolas, garden seats, a little blue Venetian-tiled pool with an impish baby faun in bronze being splashed by a water jet. There are flower beds filled with a great variety of cultivated garden annuals, perennials, and flowering shrubs and trees. Under silvery Poplars are blue Hydrangeas, while below and between them the little stream makes cool music on the hottest summer day, the interlacing boughs of the trees giving refreshing shade, their stems reflected in a quiet pool below . A dear little thatched and gabled house presides cheerfully over it all and overlooks a superb stretch of country, thirty miles to the pearly Hottentots Holland range, an ever changing vision of beauty.80

Struben's dalliance with "the native" was tolerated as an artistic eccentricity and politely ignored by the English garden writer, Marione Cran, when she visited "Luncarty" in 1925.82 Guided by the English preferences and prejudices of the foreign and local gardening press, many of Cape Town's middle class matrons remained stuck in a "petunia-marguerite-hibiscus rut."83

The wider middle class public proved as enamoured of Kirstenbosch and indifferent to its message as the society's members. The local press and publicity association promoted Kirstenbosch at every opportunity. Thus when the Cape Argus ran a competition to name "The Seven Wonders of Cape Town" in 1929, 20,000 people wrote in to place Kirstenbosch fourth behind Table Mountain and the city's two new post-war scenic experiences afforded by the cableway and marine drive.84 The number of visitors to the garden doubled between 1922 and 1925 alone, reaching over 56,000 on weekends and public holidays, and topped 115,000 by 1939.85 Few of these visitors, however, came in search of botanical enlightenment. The majority were taking advantage of the new hard road and tea house built in the 1920s or free picnic facilities amidst scenic surrounds.

In their search for a pliant audience, the Botanical Society initiated "botany rambles" for school children in 1919. Their success prompted the Cape School Board to appoint a full-time teacher to the garden in 1922 and decree that each pupil under its control pay a quarterly "nature study" visit.87 The need for teaching material also spurred botanists into the production of school textbooks. Both Marloth and Harriet Bolus, niece of the scion of colonial botany and curator of his herbarium, produced botany primers, the former in Afrikaans, for use in schools.88 They also took the lead in translating botany's sacred texts into an intelligible and affordable format for the amateur. Marloth published a dictionary of common names for plants in 1917, as an addendum to his multi-volume magnum opus, in which he privileged Afrikaans over "Kafir names" and translated folk botany into Latin binomials.89 Harriet Bolus was honorary secretary of the Wild Flower Protection Society (WFPS, see below), which began a monthly Nature Notes series in 1923 and she wrote several lavishly illustrated books from the mid-1920s onwards. These were primarily intended for "the children of this country", while a slimmer volume "written in popular language, not overburdened with scientific detail and phraseology" was aimed at their parents.90 A lecturer in botany at the university, Margaret Levyns, also produced an illustrated guide to the Cape Peninsula flora in 1929 detailing "[t]he flowers which one encounters on an everyday walk".91

The extent to which public perceptions changed as a result of these efforts is difficult to gauge, but the test case remained the wild flower trade. The Cape Town middle class continued to be intimately involved in its suppression after Union through a Wild Flowers Protection Committee formed in 1912, renamed the Wild Flowers Protection Society (WFPS) in 1920 and finally incorporated as a sub-committee into the Botanical Society in 1938.92 This body kept up sustained pressure on the provincial administrator to reform the "pitiful farce" of the Wild Flower Protection legislation, by closing loopholes and ensuring effective enforcement by the police and magistracy.93 In addition to an ever-expanding list of prohibited species, their efforts shifted the burden of proof onto the accused (1913), mandated the confiscation of prohibited flowers offered for sale (1920) and banned the hawking of flowers (1937).94 Landowners and middle class consumers were not so readily criminalised, however, as the provincial council protected farmers through the "cultivation" exemption and the WFPS its urban constituency.95

It was an open secret, however, that the latter aided and abetted the destruction of the Cape flora through its practices and custom. When flower sales became the favoured means of raising money to support the war effort during the First World War, middle class matriarchs blithely plundered Table Mountain in flagrant violation of the Wild Flower Protection Acts.96 After the war, exhibition supplanted sale as the main channel of popularisation with a proliferation of annual spring wild flower shows in south-western Cape towns, and the inauguration of a central show in Cape Town in 1922.97 The director of Kirstenbosch warned that, although "[m]uch lip-service is paid to wild flower protection on these occasions . the shows themselves are often regarded as excuses for sweeping the whole district clear of flowers."98

Lastly, there was the burgeoning street trade in wild flowers driven by middle class demand for their display in hotels, restaurants and private homes. The director of Kirstenbosch wrote despondently in 1927:

One is sometimes tempted to say that the South African hates his wild flowers . We burn our flowers, uproot them, waste them by the wagon-load, make them the subjects of senseless competition, exploit them for gain, tear them to pieces to construct monstrosities, and yet we claim to love them.99

Conserving the Indigenous: The Creation of Floral Reserves

If Kirstenbosch was having doubtful success in its public pedagogy, its other key role envisaged by Pearson - a refuge for endangered flora - was also increasingly called into question by the new science of ecology. Taxonomy had been the bedrock of both imperial botany and its Cape offshoot, and the divination and description of individual species remained central to Cape botany after Union with Harriet Bolus tripling the size of her uncle's herbarium to 100,000 specimens by 1939 and Kirstenbosch starting its own collection in 1937.100 Both the Annals of the Bolus Herbarium begun in 1918 and Journal of South African Botany, published by the Botanical Society from 1935, were given over exclusively to plant taxonomy.

The University of Cape Town's creation of a second Chair in Botany in 1918 and preference for Cambridge graduates leavened this systematic bias with ecology after the war.101 Ecology focused on the dynamics of plant communities and how competitive interaction led, through a series of graduated successions, to a stable climax community.102 This underscored the importance of human activity in disrupting and suppressing the re-establishment of the purported south western Cape "climax" flora, as well as the futility of trying to preserve it in the artificial environment of a garden103 . Veld burning and alien species now joined the wild flower trade in the rogue's gallery of threats to Cape flora and the reserve rapidly supplanted the garden as the site of its salvation from extinction.104 If human intervention could be entirely removed from an area, ecology intimated, the original climax flora would re-establish itself over time.

The idea of floral reserves was not new, but rapidly gained popularity in the wake of the establishment of the Kruger National Park in 1926. The Cape Town middle class threw its weight behind calls for the establishment of a nature reserve in the Cape Province.105 Flora lacked the appeal of big game and Cape botany did not have a proconsul of the calibre of Stevenson-Hamilton to repackage an imperial project in nationalist garb.106 What it did have was a symbiotic relationship with the local press and publicity association, which helped to promote Cape flora as a lure for both local and foreign visitors.107 The Cape Peninsula Publicity Association arranged for Kirstenbosch to exhibit at the London Empire Exhibitions in the mid-1920s and the Royal Horticultural Society shows in the 1930s. Images of Cape flora were peddled in a proliferating number of tourist brochures, postcards, and on national postage stamps or bank notes.

The Cape flora's preservation was no longer sought in the name of science or posterity, but of tourism. Thus when the president of the Botanical Society urged that Table Mountain be declared a nature reserve following the opening of the cableway in 1928, he argued that: "If the Mountain is to be 'exploited' it must also be cared for: and we do not want to take car loads of visitors up the Mountain to behold stony and flowerless wastes, blackened with fires and strewn with tins, papers and bottles."108

The salience of the "tourist movement" was confirmed by the string of resolutions and deputations emanating from South African National Publicity Association conferences in the 1930s.109 These succeeded where the WFPS had failed - in moving the Administrator to create wild flower reserves at the request of municipal and divisional councils (1932) and tightening up the province's Wild Flower Protection legislation (1937).111 Floral reserves blossomed across the Cape Province during the 1930s: 112

In addition, the chief curator of public lands, the Forestry Department, also bowed to the demands of tourism and declared its intention to preserve the indigenous flora under its control.113 By the end of the 1930s the reserve, not the botanic garden, had became the most important site of refuge for indigenous flora endangered by the flood tide of progress inundating the region.

The Indigenous and Identity

The Cape flora was long the subject of imperial classification and cultivation in Europe, and complete settler indifference in the southwestern Cape. Thus, while Cape plants stocked the greenhouses of Europe in the first half of the nineteenth century, European plants filled the public and private gardens of Cape Town till Union in 1910. The notion of the "indigenous" only acquired meaning at the Cape as the gradual devolution of political power encouraged new local, alongside older metropolitan imperial loyalties. Cape Town's middle class, heirs to the political power structures created by Responsible Government in 1873, were thus not coincidentally also at the forefront of the "discovery" of the region's indigenous flora in the final quarter of the nineteenth century.

Settler insistence on only supporting "practical science" and the absence of a university initially made botany the preserve of wealthy amateurs at the Cape. They worked as local appendages of the great imperial botanical enterprise at Kew, but later diversified away from classifying the indigenous flora to mapping its distribution and correlating this with environmental factors. The new science of "plant geography" revealed the unique and threatened nature of the southwestern Cape flora and gave Cape botany its subject and purpose. Generously endowed by its patriarch, Harry Bolus, Cape botany acquired an institutional base in the South African College.

The granting of independence to a new omnibus settler nation state in 1910, however, stripped the Cape Town middle class of political power and state patronage for its botanical mission. The latter was urgently recast in national terms, attempting to solicit state funding for a "national" botanical garden at Kirstenbosch with the promise of indigenous cash crops to facilitate national economic development. Afrikaner republicanism's antipathy towards Cape liberalism and the latter's enduring imperial empathies, however, stymied this effort and led instead to the founding of rival botanical enterprises at Stellenbosch in 1921 and Pretoria in 1923. Denied official support and fearing annexation, Cape botany turned instead to the Cape Town and metropolitan middle classes for its survival.

The formation of the Botanical Society in 1913 to subsidise the establishment of a garden at Kirstenbosch through the annual subscriptions of members marked the beginning of the transformation of Cape botany from elite science to popular pastime. The attempted re-education of urban middle class tastes away from the exotic to the indigenous ranged from the production of botanical primers for children and adults, through gardening advice, seed distribution and the criminalisation of the wild flower trade, to the strenuous promotion of Kirstenbosch and floral reserves as tourist attractions. The ambiguous position of Cape botany within the new settler nation state is reflected in its fidelity to the old imperial taxonomic project, failure to indigenise its professional or popular discourse, which spoke only of "heath" or macchia not fynbosch, and the fact that it still recruited over two-thirds of its support from Cape Town and the United Kingdom.

Cape botany thus embraced a nationalism which, as the name of its political vehicle (the National Society for the Preservation of Objects of Historic Interest and Natural Beauty in South Africa) suggests, was a peculiar ideological hybrid of cosmopolitan and nativist strands of geographic nationalism, seeking to nationalise and naturalise the imperial connection.115 Although insistent on its national credentials and allegiance, Cape botany deepened its English and imperial roots after 1910 through the active solicitation of a wider audience in the suburbs of Cape Town and the small towns of its rural hinterland, where identification with the Cape flora was more a marker of class, ethnic, regional and imperial rather than of national loyalties.

* Thanks to Andrew Bank for his initial interest, invaluable close reading and detailed commentary on numerous drafts, which went above and beyond all calls of collegiality.

1 W.J.Burchell, Travels in the interior of southern Africa, vol. 2 (London, 1822), 17. [ Links ]

2 H.Bolus, Sketch of the flora of South Africa (Cape Town, 1886), 1. See also P.MacOwan, 'Personalia of botanical collectors at the Cape', Transactions of the South African Philisophical Society (hereinafter TSAPS), vol. 4, 1886, who reports that by the mid-nineteenth century, this fashion came to be supplanted by a "mania for tropical culture, especially of orchids ... Many fine collections of Cape species, which had once been the pride of European gardens, died out slowly before the invasion of the hot-house and the watering-can." (xlviii)

3 Burchell, Travels, 17.

4 Burchell, Travels, 21-22.

5 A.W.Crosby, Ecological imperialism: The biological expansion of Europe, 900-1900 (Cambridge, 1986). [ Links ]

6 T.R.Dunlap, Nature and the English diaspora (Cambridge, 1999).

7 M.de Beer, The lion mountain (Cape Town, 1987), 61-63; F.Bradlow, Baron von Ludwig and the Ludwigsburggarden (Cape Town, 1965); A.Tredgold, The Ardernes and their garden (Cape Town, 1990) and M.C.Karsten, The Old Company's garden at the Cape and its superintendents (Cape Town, 1951).

8 Bradlow, Baron von Ludwig, 98-106; D.Fairbridge, Gardens of South Africa (Cape Town, 1924), 18 and D.P.McCracken and E.M.McCracken, The way to Kirstenbosch (Cape Town, 1988), 18.

9 Quoted in H.H.W.Pearson, 'A national botanic garden', South African Journal of Science (hereinafter SAJS), vol. 8, 1910, 40.

10 Pearson, 'A national botanic garden', 41 and P.McOwan, 'A botanical reserve-ground for the preservation of rare Cape plants', Agricultural Journal of the Cape of Good Hope (hereinafter AJCGH), vol. 9, 1896, 285.

11 MacOwan, 'A botanical reserve-ground', 285.

12 Cape of Good Hope, Report upon the Botanic Garden and Government Herbarium Cape Town, 1882 [G18-83], 6.

13 Cape of Good Hope Government Gazette, 8855, 8 May 1906, Government Notice 585 Register of nurseries of plants and trees, 1712-1714.

14 T.R.Sim, 'South African horticulture', SAJS, vol. 4, 1906, 336. [ Links ]

15 See G.L.Shaugnessy, 'Historical ecology of alien woody plants in the vicinity of Cape Town, South Africa' (School of Environmental Studies Research Report No.23, University of Cape Town, 1980).

16 Calculated from Shaughnessy, 'Historical ecology', Table 5.5.1, 254-59 and Union of South Africa, Census, 1911, Part 10 [UG32h-12].

17 Fairbridge, Gardens of South Africa, 141-42.

18 J.Noble, Descriptive Handbook of the Cape Colony (Cape Town, 1875), 39-40.

19 W.Beinart, 'Soil erosion, animals and pasture over the longer term' in M.Leach and R.Mearns, eds., The lie of the land (London, 1996), 54-72.

20 W.Tyson, 'Exotic vs native fodder plants and grasses', AJCGH, vol. 9, 1896, 570.

21 Ibid.

22 MacOwan, 'Personalia', xxx-liii and M.Gunn and L.E.Codd, Botanical exploration of southern Africa (Rotterdam, 1981).

23 See for example L.van Sittert, 'The handmaiden of industry: Marine science and fisheries development in South Africa, 1895-1939', Studies in the History and Philosophy of Science, vol. 26, 1995, 531-58 for "practical science" at the Cape..

24 MacOwan, 'Personalia', xlviii.

25 See P.J.Venter, 'An early botanist and conservationist at the Cape', Archives Year Book for South African History, vol. 15(2), 1952, 281-92 and R.Grove, 'Scottish missionaries, evangelical discourses and the origins of conservation thinking in southern Africa, 1820-1900', Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 15, 1989, 163-187 for a crude materialist explanation of the colonial botanist's demise.

26 See Dictionary of South African Biography, vol. 1 (Cape Town, 1968), 89-92 and 518-521 for details.

27 See R.Drayton Nature's government: Science, imperial Britain and the 'improvement' of the world (New Haven, 2000).

28 The seminal texts in English are Bolus, Sketch of the flora of South Africa (Cape Town, 1886); R.Marloth, 'The historical development of the geographical botany of southern Africa' SAJS, vol. 1, 1903, 251-257; H.Bolus, 'Sketch of the floral regions of South Africa' in W.Flint and J.D.F.Gilchrist, eds., Science in South Africa (Cape Town, 1905), 198-240 and R.Marloth, 'The plant formations of the Cape', SAJS, vol. 6, 1908, 246-251.

29 Marloth, 'Historical development', 255.

30 S.Schonland, 'The origin of the flora of South Africa', SAJS, vol. 5, 1907, 106.

31 See S.Schonland, 'The origin'; J.C.Smuts, 'South Africa in science', SAJS, vol. 23, 1925, 1-19; M.R.Levyns, 'Some evidence bearing on the past history of the Cape flora', Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa (hereinafter TRSSA), vol. 26, 1938, 401-24; R.S.Adamson, 'Some geographical aspects of the Cape flora', TRSSA, vol. 31, 1948, 437-464; and M.R.Levyns, 'Migrations and origin of the Cape flora', TRSSA, vol. 37, 1964, 85-107.

32 R.Marloth, 'Remarks on the realm of the Cape flora', SAJS, vol. 27, 1929, 154-55.

33 Bolus, 'Sketch of the flora', 11.

34 Marloth, 'Plant formations', 247.

35 MacOwan, 'Botanical reserve-ground', 285. The resonance with contemporary discourses of archaeology and "salvage anthropology" are unmistakable. Thanks to Andrew Bank for pointing this out.

36 R.Marloth, 'Notes on the occurrence of alpine types in the vegetation of the higher peaks of the south-western region of the Cape', TSAPS, vol. 11, 1902, Plate XXII.

37 Bolus, 'Sketch of the floral regions', 235-36.

38 See S.Dubow, 'An empire of reason: Anglophone literary and scientific institutions in the nineteenth century Cape Province', Paper presented at University of Western Cape, South African and Contemporary History Seminar, May 1999 for background.

39 J.Burman, A peak to climb (Cape Town, 1966), 14-21.

40 Burman, A peak to climb, 22-33.

41 Dictionary of South African Biography, vol. 1, 91.

42 C.Lighton, Cape floral kingdom (Cape Town, 1960), 6.

43 See 'Peter MacOwan', SAJS, vol. 7, 1909, 71-79 and R.F.H.Summers, A history of the South African Museum (Cape Town, 1975), 113-16 and 137-38.

44 Dictionary of South African Biography, vol. 1, 91.

45 Lighton, Cape floral kingdom, 7-8.

46 Burman, A peak to climb, facing 37.

47 The Mountain Club annual, vol. 8, 1903, 1.

48 National Library of South Africa (Cape Town Division), Picture Historical Archive.

49 See, for example, Cape of Good Hope, House of Assembly Debates (1905), 201, 220-222 and 301-304 and (1908), 229230 and 501-502.

50 Calculated from Cape of Good Hope, Statistical Register(1890-99).

51 Cape Archives (hereinafter CA), Department of Agriculture 149, 630, Magistrate of Simonstown to the Secretary for Lands, Mines & Agriculture, 16 December 1892. See also House of Assembly Debates (1905), 303 for Adderley Street flower sellers importing wild flowers from Caledon by 1905.

52 CA, Attorney General 1573, 1681, Francis Massey to the Attorney General, 21 February 1905.

53 Cape of Good Hope, Legislative Council Debates (1905), 198.

54 See P.Merrington, 'Heritage, genealogy and the inventing of Union, South Africa 1910', University of Cape Town, Centre for African Studies Seminar, 7 May 1997. Thanks to Andrew Bank for this reference.

55 House of Assembly Debates (1908), 229.

56 Cape of Good Hope, Wild Flower Protection Act (No.26, 1905) and Wild Flower Protection Amendment Act (No.22, 1908).

57 See Cape of Good Hope Government Gazette, 9156, 23 March 1909, Proclamation 137, Section IV.

58 House of Assembly Debates (1908), 229-230 and 501-502.

59 J.W.Mathews, 'Economic plants at the National Botanic Gardens, Kirstenbosch and the aim of their cultivation' South African Journal of Industries, vol. 2, 1919, 748-758 and R.H.Compton, Kirstenbosch, garden for a nation (Cape Town, 1965), 74-77.

60 R.H.Compton, 'The National Botanic Gardens Advisory Committee', Journal of the Botanical Society of South Africa (hereinafter JBSSA), vol. 9, 1923, 12-14; R.H.Compton, 'Kirstenbosch, South African botany and nature reserves', SAJS, vol. 22, 1924, 79-85 and Compton, Kirstenbosch, 80-81 and 97-103.

61 See, for example, Fairbridge, Gardens of South Africa; M.Cran, The Gardens of Good Hope (London, 1926); 'The Kew of South Africa', JBSSA, vol. 10, 1924, 32-34; A.Hill, 'Botany in South Africa', JBSSA, vol. 17, 1931, 6-9.

62 'Notes and news', JBSSA, vol. 14, 1928, 2.

63 On, for example, the language of Cape botany see E.J.Moll and M.L.Jarman, 'Clarification of the term fynbos', SAJS, vol. 82, 1984, 351 and J.W.Bews, 'An account of the chief types of vegetation in South Africa with notes on plant succession', Journal of Ecology, vol. 4, 1916, 129-59. Moll and Jarman credit Bews with "coining" the term fynbosch to describe the Cape flora in 1916, but Bews merely reported the local use of the Dutch word "to designate any sort of small woodland growth, which does not include timber trees." Its use in scientific discourse is of far more recent origin and part of Cape botany's self-conscious "Afrikanerisation" after 1960.

64 See P.Beukes, Smuts the botanist (Cape Town, 1996), 11-80; Compton, Kirstenbosch, 118; E.A.Walker, 'An old Cape frontier', JBSSA, vol. 22, 1936, 8-11; H.B.Thom, Stellenbosch 1866-1966: Hondered jaar hoer onderwys (Cape Town, 1966), 108-110 and Dictionary of South African Biography, vol. 2, 513-514. The first Afrikaans labelling appeared in the garden in 1930 and Van Riebeeck's hedge was declared a national monument in 1936.

65 N.S.Pillans, 'A South African botanic garden', AJCGH, vol. 36, 1910, 638-41 and H.H.W.Pearson, 'A national botanic garden', SAJS, vol. 8, 1910, 48 and 50-51. See also the 50th and 75th anniversary histories by Compton, Kirstenbosch and MacCracken and McCracken, The Way and D.P.McCracken 'Kirstenbosch: The final victory of botanical nationalism', Contree, vol. 38, 1995, 30-35. Despite its title, the last offers a teleological rather than a critical history of Kirstenbosch by a Natalian pleading his preferred local interest - the purported neglect of the Durban botanical garden after Union.

66 See H.H.W.Pearson, 'A state botanic garden', The State in South Africa, vol. 5, 1911, 643-652; H.H.W.Pearson, 'The Botanical Society and the National Botanic Gardens', JBSSA, vol. 1, 1915, 8-9 and Compton, Kirstenbosch, 31-46.

67 See Union of South Africa, House of Assembly Debates(1913), 2164-2179.

68 Compton, Kirstenbosch, 44. Pearson had mentioned a sum of £32,000 in 1910.

69 Compton, 'Kirstenbosch, South African botany', 83.

70 Pearson, 'A national botanic garden', 44.

71 H.Bolus, 'The proposed National Botanical Garden', SAJS, vol. 8, 1910, 421. Also Compton, 'Kirstenbosch, South African botany', 91.

72 F.W.Fitzsimons, 'Economic natural history and why it should be taught in schools', SAJS, vol. 16, 1918, 581.

73 'Birds-eye view of the National Botanic Gardens, Kirstenbosch', JBSSA, vol. 4, 1918.

74 Calculated from Compton, Kirstenbosch, 161-68

75 Compton, 'Kirstenbosch, South African botany', 90.

76 See 'Notes and news', JBSSA, vol. 8, 1922, 2 and 'Notes and news', JBSSA, vol. 12, 1926, 3 for the lack of member interest in either nationalism or scientific botany.

77 'Notes and news', JBSSA, vol. 7, 1921, 3.

78 E.Struben, 'A garden of promise on Table Mountain Side', JBSSA, vol. 12, 1926, 9.

79 Ibid, 10-11.

80 Ibid., 11.

81 Cran, Gardens of Good Hope, 180.

82 Ibid., 43-44.

83 'Notes and news', JBSSA, vol. 13, 1927, 3.

84 'Notes and news', JBSSA, vol. 15, 1929, 5.

85 Counting only began in 1919 and was confined to Saturday afternoons, Sundays and public holidays. The only published figures for this period are in 'Notes and news', JBSSA, vol. 12, 1926, 3 and Botanical Society of South Africa, Annual Report, (1928-1939) in JBSSA.

86 J.Hutchinson, A botanist in southern Africa (London, 1946), 97.

87 Compton, Kirstenbosch, 149-150.

88 R.Marloth, Die plantewereld van Suid-Afrika, Deel I (Cape Town, 1919) and H.M.L.Bolus, Elementary lessons in systematic botany based on familiar species of the South African flora (Cape Town, 1919).

89 R.Marloth, Dictionary of the common names of plants with list of foreign plants cultivated in the open (Cape Town, 1917).

90 H.M.L.Bolus, A first book of South African flowers (Cape Town, 1st Edition 1925 and 2nd Edition 1928); H.M.L.Bolus A second book of South African flowers (Cape Town, 1936) and A.Handel Harmer, Wild flowers of the Cape: A floral year (Cape Town, n.d. c1929).

91 M.R.Levyns, A guide to the flora of the Cape Peninsula (Cape Town, 1929), iii.

92 See Journal of the Mountain Club of South Africa (hereinafter JMCSA), vols. 15-19, 1912-16; JBSSA, vols. 6-25, 192039 and Handel Harmer, Wild flowers of the Cape, 97-100 for the activities of the WFPS.

93 'Notes and news', JBSSA, vol. 11, 1925, 6.

94 See Province of the Cape of Good Hope, Wild Flower Protection Ordinance (No.10, 1913); Licences Amendment Ordinance (No.16, 1920) and Wild Flower Protection Ordinance (No.15, 1937).

95 'Notes and news', JBSSA, vol. 10, 1924, 3-4.

96 'The protection of wild flowers', JMCSA, vol. 18, 1915, 107.

97 Lighton, Cape floral kingdom, 73-82.

98 'Notes and news', JBSSA, vol. 12, 1926, 5 and 'Notes and News', JBSSA, vol. 13, 1927, 3-4.

99 'Notes and news', JBSSA, vol. 13, 1927, 3.

100 H.Phillips, The University of Cape Town 1918-1948: The formative years (Cape Town, 1993), 55-56 and 351-52 and Compton, Kirstenbosch, 78-86.

101 Phillips, University of Cape Town, 50-55.

102 D.Worster, Nature's economy: A history of ecological ideas (Cambridge, 1985), 205-218 and J.W.Bews, 'The ecological viewpoint', SAJS, vol. 29, 1931, 1-15.

103 The key texts are R.S.Adamson, 'The native vegetation of Kirstenbosch', JBSSA, vol. 11, 1925, 19-23; R.S.Adamson, 'The plant communities of Table Mountain: I Preliminary account' Journal of Ecology, vol. 15, 1927, 278-309; R.S.Adamson, 'The vegetation of the south west region', JBSSA, vol. 15, 1929, 7-12; essays by Adamson and Levyns in R.S.Adamson, ed., The botanical features of the south western Cape Province (Cape Town, 1929); R.S.Adamson, 'The plant communities of Table Mountain: II Life form dominance and succession', Journal of Ecology, vol. 19, 1931, 30420; and R.S.Adamson The vegetation of South Africa (London, 1938).

104 See M.R.Mitchell, 'Some observations on the effects of bush fires on the vegetation of Signal Hill', TRSSA, vol. 10, 1922, 213-32; Marloth, Levyns, Pillans and Botha, 'Symposium on veld burning', SAJS, vol. 22, 1924, 342-352; M.R.Levyns, 'Veld burning experiments at Ida's Valley, Stellenbosch', TRSSA, vol. 17, 1929, 61-91; J.F.V.Phillips, 'Fire; Its influence on biotic communities and physical factors in South and East Africa', SAJS, vol. 28, 1930, 352-367; R.S.Adamson, 'The plant communities of Table Mountain: III A six year's study of regeneration after burning', Journal of Ecology, vol. 23, 1935, 44-55 and M.R.Levyns, 'Veld burning experiments at Oakdale, Riversdale', TRSSA, vol. 23, 1935, 231-44.

105 MacOwan, 'Botanical reserve-ground'; 'Notes and news', JBSSA, vol. 12, 1926, 5-6; 'Notes and news', JBSSA, vol. 13, 1927, 4-5 and S.H.Skaife, A naturalist remembers (Cape Town, 1963), 52-56.

106 J.Carruthers, The Kruger National Park: A social and political history (Pietermaritzburg, 1995), 47-66.

107 See, for example, 'Notes and news', JBSSA, vol. 10, 1924, 2 and 'Notes and news', JBSSA, vol. 20, 1924, 3 for the tea house and silver tree appeals run by the Cape Times on behalf of the gardens.

108 'Notes and news', JBSSA, vol. 14, 1928, 5.

109 A.J.Norval, The tourist industry: A national and international survey (London, 1936), 296-311. [ Links ]

110 C.L.Engelbrecht, Money in South Africa (Cape Town, 1987), 98.

111 'Notes and news', JBSSA, vol. 18, 1932, 4 and Province of the Cape of Good Hope, Wild Flower Protection Ordinance (No.16, 1937).

112 R.H.Compton, 'Local nature reserves', JBSSA, vol. 18, 1932, 10-16 and F.R.Long, 'Parks and publicity', JBSSA, vol. 25, 1939, 6-9.

113 E.J.Dommisse, 'Nature conservation', JBSSA, vol. 21, 1935, 5-6.

114 Compiled from Lighton, Cape floral kingdom, 83-107; Compton, Kirstenbosch, 49 and 56-57 and Province of the Cape of Good Hope Official Gazette (1918-1939). The only other two flower reserves established in this period were the Mount Currie division (including Kokstad municipality) (1934) and Matatiele municipality (1939) in the Transkei.

115 See E.Kaufmann, 'Naturalising the nation: The rise of naturalistic nationalism in the United States and Canada', Comparative Studies in Society and History, vol. 40, 1998, 666-695. Also J.Comaroff and J.L.Comaroff, 'Naturing the nation: Aliens, apocalypse and the postcolonial state', Journal of Southern African Studies, vol. 27, 2001, 627-51 for a contemporary riff on these themes whose predictable post-modern excess fails to disguise either its historical illiteracy or unacknowledged debt to Mike Davis' far superior Ecology of Fear (New York, 1998).