Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.28 no.1 Cape Town 2002

From pictures to performance: early learning at the Hill1

Andrew Bank

University of the Western Cape

A Garden Myth2

There is a story that scholars like to tell about /Xam informants living in the Mowbray garden of Wilhelm Bleek and Lucy Lloyd. There is, I intend to argue, precious little evidence to support this story. But as Louise White reminds us, fictions and inventions - lies might be too strong a word in this instance - are often "the most telling".3 This applies as much to scholarly as more popular forms of knowledge.

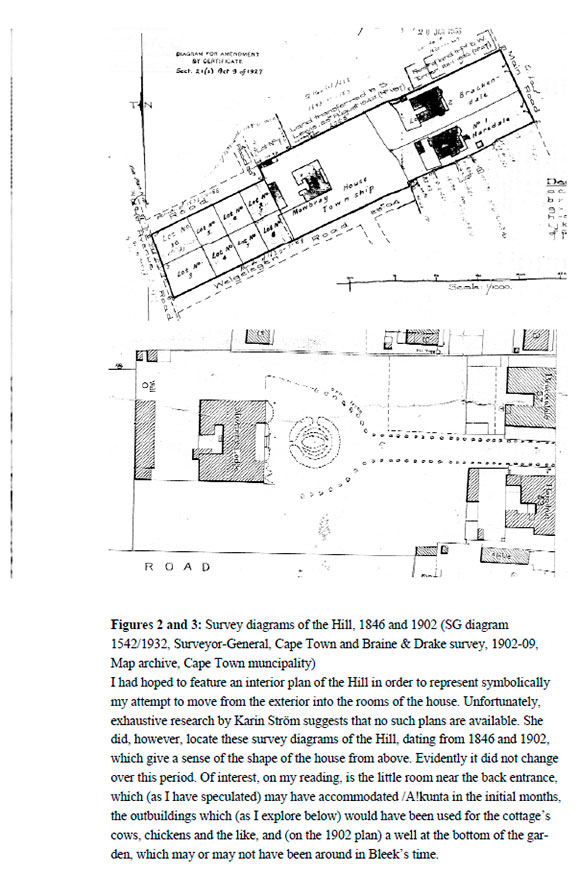

As I read the evidence from letters, notebooks and photographs in the Bleek-Lloyd Collection and elsewhere, the case seems relatively clear. When Bleek and Lloyd's first informant, /A!kunta, was transferred from the Breakwater Prison to their home, the Hill, on the 29th of August 1870, he was kept in "a room with a grated window" under guard by a former prison warder with a gun.4 This room might well have been the little appendage at the back of the house near the rear entrance (see the survey diagrams in figures 2 and 3). In later correspondence, Bleek explained that he wanted the informant "at his dwelling place" and that the layout of the Hill, where the Bleek and Lloyd families had taken residence in December of the previous year, allowed for the exercise of "proper surveillance".5 He also wrote of "living in a house with sufficient accommodation" to receive /Xam informants,6 and included generous allowances for "preliminary costs" for receiving them (of about four and six pounds for /A!kunta and //Kabbo respectively). This in an inventory of expenses that he drew up to support a claim for financial assistance from the Cape government. The inventory also makes explicit mention of costs of "board" as well as food, clothing and tobacco.7

When //Kabbo joined /A!kunta at the Hill on the 16th of February the following year, Bleek seemingly dispensed with the services of the former warder. Although he does at one point refer to having employed this man to watch over "them", his list of expenses indicates that he only paid him for the five months that he spent guarding the "first bushman",8 presumably from the 29th of August to before or around the 16th of February.

There is no evidence to suggest that /A!kunta or //Kabbo moved into any huts in the garden - whether in letters written by Wilhelm Bleek, Jemima Bleek or Lucy Lloyd at the time or in passing notes of vocabulary recorded in their notebooks, let alone in any published writings. In any event such a living arrangement would have made little sense. Neither /A!kunta nor //Kabbo were fighting fit when they arrived at the Hill. /A!kunta had contracted a consumptive illness during six months at the Breakwater Prison9 and //Kabbo was of a mature age. The notebooks provide much evidence of illnesses during their early months of residence at the Hill, especially colds, as well as home nursing and respective visits to a doctor.10 Attempts to keep them healthy, not to mention "tolerably fresh", "clean" and "tidy" (the descriptive terms used by Bleek at the time),11seem thoroughly incompatible with wet winters spent in a bush hut. /A!kunta and //Kabbo left the Hill in October 1873.

The only whiffs of evidence to sustain the garden myth come in the form of photographs taken by Wilhelm Hermann some time between June 1874 and January 1875.12 These photographs were taken outside the wooden fence bordering the Hill and a side of the house is just visible in the background. In the foreground stands their third informant, =Kasin, and his family in front of a shelter of bushes rather than a hut.13 Exactly what function this shelter played in domestic arrangements at the Hill is not possible to establish, but any suggestion that it represented permanent outdoor accommodation is expressly contradicted by Bleek. In a letter written to George Grey that January, he explained: "With a few months interval I have had Bushmen staying in my house for four years and a half - at one time as many as seven ... Now I have only one [Dia!kwain, their fourth informant]." [my emphasis]14 =Kasin and his family were among the seven house-guests he was referring to here.

And that's as far as the evidence goes. There is nothing to suggest that Dia!kwain was moved or chose to move into a garden hut when the family relocated to larger premises at Charlton House in February 1875. A sketch map of the layout of Charlton House, which (the handwriting suggests) was drawn up by Jemima Bleek, plots a croquet ground, a "fontein", neighbouring stables, but no hut or huts, whether for the accommodation of Dia!kwain (up to June 1876) or /Han=kasso during 1878 and 1879.15 In the case of Dia!kwain and /Han=kasso, as with /A!kunta and //Kabbo, their relatively close relationship with the Bleek and Lloyd families, and with Lucy Lloyd in particular (the texture of which emerges very clearly from the thousands of pages of testimony in the notebooks in the Bleek-Lloyd Collection) runs counter to any notion of enforced or voluntary spatial separation.

It may be that domestic arrangements with later visitors at Charlton House provided the seeds for the scholarly myth. In February 1879, after a visit to Charlton House, Robert Moffat's daughter reported that "Mrs Bleek has a Bushman family - father, mother and two children - living on their premises."16The family referred to here is that of Piet Lynx, a Koranna visitor, though whether "premises" implied residence outside the house is not absolutely clear. The only actual evidence of garden huts relates to those built by !Kung boys who stayed at Charlton House between 1879 and 1882. A photograph taken at the time shows the four boys in front of what is clearly a bush hut. But even in this instance it does not appear to have been used as sleeping quarters. Edith and Dorothea Bleek wrote in 1911 that:

They [the !Kung boys] built themselves a hut of gum-boughs as a playroom. Here they cooked wild doves that they shot ... A second bush hut they made as a gift for the children of the house. It was big enough to use as a summer-house.17

The Making of the Myth

So much for the evidence. How is it that a story about /Xam informants living in the garden has attained the status of an almost taken-for-granted historical "fact" in existing scholarly accounts? And, more importantly, why?

A chance interview that Eric Rosenthal conducted with Wilhelm Bleek's daughter, Dorothea, some time between 1945 and 1948 (the year of her death) in her "rambling" Newlands home produced some of the "evidence" that latter-day scholars have seized upon. In a passage that has been quoted and requoted, Dorothea Bleek "recalls":

He [Father] asked whether it might be possible to allow some Bushmen to work for our family, so that he could interview them in the peace of our own home in Mowbray. This was approved of by Sir Philip [Wodehouse], and we then had a few of them as servants. You can imagine that a Bushman, who has not even learnt to live in a house, and who knows nothing of cultivating the soil, did not make a particularly good house-boy ...18

Even if we credit this as a reliable source of evidence - Dorothea now in her mid-seventies "recalling" in paternalistic terms a period almost two years before she was born,19 being cited by Rosenthal whose accounts are full of romanticisations of her ("the world's expert on the Bushman") and her father ("the Doctor") - the reference here to the Bushmen "not even [having] learnt to live in a house" clearly refers to their way of life before arriving at the Bleek's home rather than to any subsequent domestic arrangement, as authors like Karel Schoeman assume.20

It is difficult to know whether a passing reference in Laurens van der Post's The Heart of the Hunter, published in 1961, played any role in breathing life into the garden myth. His books about Bushmen, however economical with the truth, were enormously influential.21 In introducing "a story I once heard from Faanie Richie who had known Lucy Lloyd and Wilhelm Bleek", he claims that they "had gained permission from the government to house at the bottom of their garden in a suburb of Table Bay a number of Bushman convicts from the national gaol."22 Perhaps a reading of van der Post informed (or confirmed) the view of "Dr Margery Scott, granddaughter of W.H.I.Bleek." In what seems to have been the decisive moment in the transfer of a popular into a scholarly myth, Janette Deacon cites Scott as the source for her claim that: "Seven adults lived at different times at the Bleek home in Mowbray (in huts that they built in the garden ...)"23 Scott or Deacon may also have had the Hermann photographs in mind.

From there the garden myth began to sprout and soon it was developing buds and branches. By 1991 Stephen Watson felt confident enough to claim, in the introduction to poetic rerenderings of a number of the /Xam narratives: "We know [my emphasis], for instance, that the /Xam informants lived in grass [his invention] huts at the bottom of Bleek's home in Mowbray."24 In an article in the sumptuous Miscast collection, published in 1996, Martin Hall wrote rather dramatically that "the routine of having 'Bushmen' living in the garden can be read as conforming to the exigencies of restricting and codifying wild habits," and that a passage from one of Bleek's reports reads like that of "the keeper of a zoological garden." He even added what might easily be misconstrued as an additional bit of "evidence", though he is not explicit about what status he accords it.

The article begins with a "quote" from the diary of Thomas Maclear, Bleek's neighbour in April 1875, shortly after the Bleek and Lloyd families had moved to Charlton House: "Disgusting ... in the Paddock ... The person, a Bushman of Dr Bleeks. Puks pulled him off ..."25 From this "quote" it is not only unclear who or what "Puks" might be, but also, more importantly, whose "paddock" is being referred to. "Lamentable" and spidery as Maclear's diarised references are, the original - on my reading - records: "Disgusting trespass [this clearly legible] in the Paddock captured [?] by Charles Piers. The person, a Bushman of Dr Bleeks. Piers pulled [??] him off ..." [my emphases and parentheses] An earlier reference in the same diary (later crossed out) reads: "trespass of Dr. Bleeks Bushman in my Paddock" (10 Feb. 1875).26 So the "Paddock" was evidently that of Maclear and "Puks" was, in fact, Charles Piers, one time Superintendent of Convicts at the Breakwater Prison.27 Other diarised references reveal that Piers was a regular visitor to Grey Villa (Maclear's home).

So too Lewis-Williams has added fictive twists to the garden myth. In his long-awaited compilation of narratives from the Bleek and Lloyd collection, he has the researchers actually recording the /Xam narratives "in their colonial garden" (whether or not in any huts is unstated). Here we read of notebooks being shuffled "to and fro between the house and the garden where they [Bleek and Lloyd] sat conversing with //Kabbo and the others."28 Where he derives this theory is a mystery as there is abundant evidence (published as well as unpublished) that the recording sessions took place inside the house.29

But more of this later, and enough too of the making of the myth. It is evidently in full bloom. The more interesting issue is why this myth continues to exercise such a hold in the imaginations of scholars (let alone any continuing popular currency). Philip Curtin's analysis of the invention of an obviously much more significant and politically charged "historical fact" - the claim that 15 million Africans were transported across the Atlantic Ocean as slaves - is suggestive. What Curtin's case study of making-fiction-into-fact demonstrates is, firstly, the extent of intercitation and cross-reference in the construction of scholarly knowledge - what some like to call "intertextuality" and Edward Said termed "the sheer knitted-together strength of discourse".30 Secondly, Curtin shows how this "fact" performed ideological work and has quite obviously partisan origins. He traces it back to Edward E.Dunbar, an abolitionist publicist of the 1860s.31

Without presuming any sinister motives on the part of scholars writing about the Bleek-Lloyd project, I would suggest that the garden myth in its Mowbray manifestation does clearly serve a function that might be termed "ideological". It seems to me to illustrate three things in particular. To begin with, images of /Xam informants living in a colonial garden and even, in Lewis-Williams' imagination, narrating traditional stories there, provides the kind of romanticised gloss on the interactions between the researchers and their informants that I have criticised at length elsewhere.32 Secondly, the willingness of scholars simply to accept the story without further probing reveals, to put it politely, an incurious attitude towards "context", that is, towards the specific and changing historical circumstances surrounding the products of Bleek and Lloyd's work with the /Xam. The literature on the Bleek and Lloyd project is, in my view, very long on text and short on "context". We have half a dozen book length textual compilations and rerenderings of /Xam stories,33 and yet are not even sure whether those, or some of those, who told the stories lived in the researchers' house or in huts in their garden. This issue is surely of some import, as the degree of physical proximity between the researchers and their informants is a crucial aspect of the "psychological context" informing such communications.34

And herein, I feel, lies the real significance of the garden myth. It functions through a graphic metaphor (with visual traces of the Hermann photograph) to separate conceptually the world of the house, site of the colonial culture of Bleek and Lloyd, and the natural world, site of huts and traditional stories. Where analyses of the Bleek-Lloyd collection do pay attention to "context" - in the form of biographical sketches of Bleek and Lloyd, of their /Xam informants, or of the historical background of Bushmanland in the 1860s35 - contextual features tend to be separable into colonial and Bushman worlds. The knowledge produced in interactions in the Mowbray home is, it sometimes seems assumed, directly transmitted from the informants' memories via the hands of the researchers onto the pages of notebooks, and encountered today simply as "voices from the past."36 Even where the project is cast as "collaborative", the kind of romanticised and overly general terms in which such collaboration is conceived37does little to aid understanding of the contingent, multiple, historically situated encounters involved.

Once we confront the fact that the /Xam informants did live in the same house, sharing much of the domestic culture of the Bleek and Lloyd families (though clearly under conditions of strain and constraint as Guenther has highlighted),38 we can begin to interpret the notebooks as a record of "situated discourse", of complex and changing communicative events. This applies not only to the recording process itself - which adopting the terminology of anthropologists like Duranti and Goodwin, I view as "the focal event" of these encounters39 - but also to all those other everyday interactions that make up relationships between people sharing the same space. And as I hope to demonstrate below, the notebooks abound with information that allows us to reconstruct -even in a mode of "thick description" - the relationships and spaces of the Bleek-Lloyd home(s). This article presents the first chapter of these encounters with the focus, first, on reconstructing the physical setting within which they were played out and, second, on analysing the dynamics of the learning process.

The Hill

I am not the first to show an interest in the physical setting and objects associated with Bleek and Lloyd's /Xam research. In the article referred to above, Hall investigates what he terms "the archaeology of the encounters" between the researchers and their informants. The "material traces" he identifies - "books, photographs, buildings, paintings"40 - are perhaps the most important, but there were many others. Through a very close reading of the vocabulary recorded in the early notebooks, together with other material traces in the Bleek-Lloyd Collection, I will now attempt to probe some of the more intimate spaces of their Mowbray home.

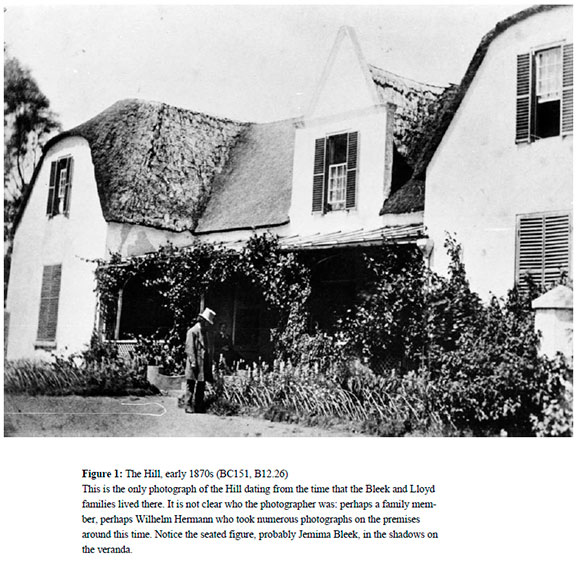

The Hill (later called Mowbray Lodge) was situated on the lowest slopes of Devil's Peak, some 30 or 40 metres from Mowbray's main road.41 Jemima Bleek characterised it as "old" and "damp" in her letters - it was built in 1843. Its elevated position would have afforded views of the newly built railway station and surrounding countryside, and countryside it was, more peri-urban or rural than urban. It was a country cottage, or "farm" (as a much later photograph of the house would still be described), adjoining Mowbray "village" and linked to the centre of town (Bleek's place of work) by horse-drawn cab and, from 1865, by rail.

To work from the outside perimeters of the property inwards, the Hermann photographs mentioned above show a wooden fence marking off its boundaries with sturdy poles joined by logs. In retrospective memoirs, Edith Bleek (we can assume it was not Dorothea as she was too young) remembered "a bit of green beyond the garden gate."42 This was on the downward slope and access route to the main road. Vocabulary recorded in the early weeks suggests that the garden featured arums and casuarina, while snapdragons and a creeping bougainvillea are visible in the photograph below.43

The survey diagrams show outbuildings, which I imagine to have been used for the accommodation of domestic stock. Apart from numerous references to cats, kittens and dogs, there is frequent mention in /A!kunta's early communications of cows ("beest"), chickens ("huhness") and, at one point, a horse: "I led (or lead) the horse, the horse is wild."44 There are even some references to an ostrich, though I find it difficult to imagine that it was kept as a household pet.

The Bleek sisters also mention a family donkey called "Neddy", and there is reference to a donkey in the earliest notebooks.45 Reconstituting this mammalian component is a tricky business, however, as most of the vocabulary recorded in the early days is of /A!kunta identifying objects from pictures. It is often difficult to separate this world of pictures from the world of everyday life at the Hill. There are a few pointers, however. Sudden rather than more gradual shifts in word choice suggest the paging through of picture books. The conditions of possibility are another obvious contraint - it is fair to assume that lions or elephants were not resident at the Hill. And references to movement, and especially the senses - smelling, touching, hearing - can be assumed to signify a more immediate presence. It is on these grounds say that "ostrich smells thee ... he 'loep weg'" or "the ox is right angry (pokes?); the ostrich is cross, it kicks us"46 suggest to me a physical presence rather than a picture.

My reconstruction of the interior house is equally reliant on hunches and educated guesswork. As noted above, /A!kunta was under guard for the first five months in the "room with a grated window". Whether //Kabbo joined him here or they moved into another room from February is difficult to say. The expense for the preparation of the house for //Kabbo's arrival suggests the latter. Bleek evidently slept upstairs at Charlton House47 and the same upstairs-downstairs arrangement may have applied at the Hill. During an early recording session, /A!kunta comments on a child walking "above the house (upstairs),"48 perhaps in a bedroom. This must have been Edith, then seven years old, as Mabel was not yet of walking age.49

Bleek's study, I am inclined to believe, was on the ground floor, presumably on one of the wings of the house, with a window separating it from the veranda shown in the photograph. It must have been a relatively large room to accommodate his voluminous library. The numbers entered in the front cover of his books run into the eight and nine hundreds. The contents of his bookshelves can be reconstructed in detail, since many of his books were donated by Dorothea to the University of Cape Town's library between 1940 and 1947. They have been reconstituted as "a special collection" through meticulous detective work by Tanya Barben.50 Without getting lost in the shelves, a pleasure I wish to reserve for a future occasion, we may note Bleek's own classification of his collection in an earlier will (January 1866), as comprising of works in "African, Australian, Polynesian, American and Basque Phililogy." He evidently felt that these books would have been of sufficient value to interest buyers from "one of the great European libraries, such as the Berlin or British Museum."51

Trips to Europe in 1860 and 1869 ensured that his collection kept abreast of the latest scholarship. Inscriptions in many volumes provide evidence of constant updates. His philological collection was accompanied by a growing number of works in foreign languages: dictionaries, lists of vocabulary and translations of sections of the Bible from the native languages of Australia, New Zealand and India. It seems from a letter written in July 1870, on the eve of /A!kunta's move to the Hill, that the Khasi language (an Indian language) was then a particular preoccupation of Bleek's and one which he saw as of being special relevance to the understanding of lingusitic evolution and classifica-tion.52 Occasional works of folklore - say of Maori and Native American tales -were also procured and shelved at this time, anticipating the beginnings of a widening of his scholarly interests. Protecting this valuable private collection from fire (and perhaps "damp") was, in fact, one of the reasons for the family's later move to Charlton House.53

His desk I imagine as orderly, its drawers brimming with letters of correspondence from publishers, close friends like "Sir George", William Colenso and his cousin, Ernst Haeckel. Bleek also kept in regular contact with his mother and siblings in Germany, and kept copies of their letters as well as those that he and Jemima had exchanged during their courtship. One of his drawers may also have contained the "Azimuth compass" that he listed amongst a few treasured items in his wills. This I assume to have been a momento from his Niger Expedition in 1854.54 A sequence of objects listed by /A!kunta while working with Lloyd - "polished black paper weight, polished black marble, polished black button, black wooden pencil, wooden ruler"55 - give a colour-coded glimpse of what may have lain on the surface of the desk, though it is difficult to know how /Xam translations of such fetish objects of the literate would have been derived.

The study walls were perhaps adorned with images of mentors and a map. A fine pencil sketch of Haeckel as a teenager, and portraits of Bleek's most influential teachers in Bonn and Berlin - Carl Ritter, F.C.H.Dahlmann and F.R.Rietschl (signed and inscribed variously in Latin and German)56 - were likely to have been displayed. So too perhaps was the certificate from 1856 which confirmed that he was a corresponding member of "Die Kaiserliche-Königliche Geographische Gesellschaft" and, in my mind's eye at least, a general map of Africa that he culled from its place between the "Generalkarten" of Asia and America in A.Steiler's Hand-Atlas über alle Theile der Erde und das Weltgebaude (1860). He applied light blue, yellow and green to mark off on the map various regions of importance in his system of classifying African languages.57

Jemima Bleek's sewing machine, which would be used to mend the clothing worn by /A!kunta, //Kabbo and later informants, probably occupied some pride of place in the sitting room, which I imagine as a central area on the ground floor. A sewing machine of unspecified make is mentioned as a separate item in the wills. There are repeated references to "needles" in the vocabulary recorded in the early days, as, for example, in this sequence which follows my own scripting:

/A!kunta: "thou puttest it in (as a needle into a box), thou layest it down (as a needle upon a table), thou stickest it in (as a needle into the table upright)"

Lloyd: "I take it out (as a needle out of a box)"58

The kitchen, presumably on the ground floor near the back of the house (adjoining /A!kunta's room?), is unlikely to have contained much out of the ordinary. Bleek's newly allocated pension allowance of 150 pounds was very modest given the size of his household. An inventory of items purchased by Jemima Bleek in July of some unspecified year (perhaps 1871), gives a sense of the kind of household diet of the family and informants: "bread, sausage, eggs, fruits, veg., honey, meat, bread, fish. July 5: bread, meat, fillet, cake, fruit, railage on meat ... lemon, milk, greens, fish, fruit man, oranges, peaches."59 The Bleek sisters' memoir includes reference to fruit trees, though it is not clear whether they were referring to the Hill or Charlton House.60 It may have been these trees rather than the "fruit man" that produced some oranges referred to in passing.61 Liquid refreshments evidently included coffee for researchers and informants, and wine and brandy for select members of the household. A budgetary allowance for tobacco in the inventory of expenses Bleek put before parliament reveals that the informants were also permitted minor indulgences.62

Transcription and translation

"The focal event" of social encounters was the recording session. Lucy Lloyd's notebooks begin on the day of /A!kunta's arrival at the Hill and her records are meticulously dated for the first few months of recording. They can be read as a diary of life and learning at the Hill. Bleek began to record a few days later, on the 3rd of September. Lloyd was almost invariably present at these sessions, but the content of the notebooks reveals that they seldom recorded at the same time.

The sessions took place indoors, though passing vocabulary about say plants, trees, insects or domestic animals may have been recorded outside. My own reading suggests Bleek's study as the most likely venue in the early months.

On the 23rd of November, Lloyd quotes /A!kunta as saying "ik set [i.e. sit] the hut [i.e. hoed] is die plaak [i.e. op die plek] daar" [my parentheses], to which she adds: "really on the window ledge in the veranda, while we are in the study." Such meticulous attention to detail makes Lloyd's notebooks a particularly rich source for the kind of reconstructive work that I am interested in here. Some days later, she noted: "I think it is a cat (of a noise heard on the garden bed under the window),"63 reinforcing my sense that the sessions took place on the ground floor in one of the wings of the house. The extensive use of travellers' accounts during the first fortnight of /A!kunta's stay (which I will discuss below) would also suggest Bleek's study as the probable location of the early learning sessions.

Some time later, perhaps a few months after //Kabbo's arrival, they moved venue. In April 1872, Bleek reported that the sessions now took place "in the sitting room" for a number of hours "(sometimes four in the day)." This was usually in the evenings after his working day, as it could keep /A!kunta and //Kabbo doing "regular brain-work up to what, for them, were late hours."64 A small doodle-sketch by Bleek on the left-hand page of one of his notebooks suggests that a fixed seating arrangement may have become the norm. The sketch plots a (sitting room?) table with six seats. Bleek and Lloyd's seats, marked "B" and "L", are each separated by a single seat (marked "E" for empty), from those of /A!kunta (Stoffel) and //Kabbo (Jantje), marked "S" and "J" on the sketch.65Without wanting to make too much of such an odd snippet of evidence, it does hint at a set pattern, as well as a spatial separation of the researchers at one side of the table and the informants at the other.

On the table, we should imagine one of Lloyd or Bleek's notebooks. The manner in which they went about recording has been documented, to some extent, by Lewis-Williams. As he notes, the right hand pages of the books were divided into two columns: one for /Xam and the other for the English translation.66 It is interesting that while Bleek entered the /Xam versions in the left hand column of the pages of his notebooks, Lloyd recorded English in the left hand column of hers. This may have been because, in the initial weeks and months, she first entered the English vocabulary and then the /Xam, as the latter had to be scratched out and amended so many times. Her comments in the margins reveal that she was still struggling with the sounds of this "ferociously difficult language." 67 As /A!kunta could hardly fail to notice, "de Bushman tal praat is baie swer die noi." ["Speaking the Bushman language is very difficult for the young lady."]68

The left hand pages of the notebooks were left for recording additional information about stories or ethnography, or sometimes in later notebooks new stories or snippets of information. They can be read almost as footnotes. Even after a pattern of "story-dictation" got underway from about July or August of 1871, they remain a rich and underutilised source of contextual information - not only about the stories, but also about the manner of their telling and the interactions between informants and researchers.

The dates of recording and translation are frequently entered in the notebooks, though in later years they feature more sporadically. Lloyd was always more diligent in this regard than Bleek. Other scholars have generalised about the dates of translation, not surprisingly, according to the arguments they have wanted to make. Lewis-Williams, in an effort to emphasise the authenticity of the records as an ethnographic aid in reading San rock art, maintains that translations were usually done "within a few days" following the recording of the /Xam text. Guenther, in drawing attention to what he variously describes as the "stilted", "clinical" or "artificial" nature of recording sessions, maintains that the translations were done "days, weeks, months, or even years later," and, at times, by a different informant (to boot).69 The truth is that the practise varied enormously over the decade of recording and, if we are to hazard a generalisation, it is perhaps fair to say that in the earlier days the dates of recording and translation were usually closer together than they were to be later. But it depended very much on the narrative and its perceived importance to the researchers. Rambling stories that spanned years, like "Mantis and Moon" narrated by //Kabbo, were less likely to be translated immediately than shorter stories or ethnographic commentary that seemed of more immediate interest.

The text and translation were later "corrected" (the term used by the researchers) with the help of informants. This did usually happen a few months after initial recording. In the case of Lloyd's first entries, for example, the dates entered in the margin indicate that the corrections were done in late October. The potentially confusing to-and-fro sequence: 30 August 1870 (page 3), 22 October (page 6), 24 October (page 9), 31 August (page 11), 25 October (page 12), 1 September (page 16) should be read as an overlay of dates of recording and dates of correction.70

Lloyd and Bleek evidently used a number of props to assist them in transcription and translation. The most important of these were dictionaries or "Bushman manuscript vocabularies". For each new word, the researchers (usually Bleek) made a note of the term and its translation on a piece of paper, cut it out and pasted it in alphabetical sequence in dictionaries-in-the-making. There were /Xam-English as well as English-/Xam versions of sequentially numbered volumes. The former, for example, based only on the first year of recording, ran to 553 pages. The four books were arranged from words starting without clicks to those starting with clicks. Accordingly, the spines of these musty volumes make for unconventional reading: "Vol. I: A to W; Vol. II: Y to =; Vol. III: !; Vol. IV: //-0."71

Another aid used by Lloyd was an alphabet written into the opening page of a few of her notebooks. It is likely that she used the letters to assist her in creating an accurate transcription of the highly complex sounds that she was hearing from the mouths of her informants. It may also have been used to teach /A!kunta and //Kabbo the rudiments of literacy. We know, for example, that Bleek and Lloyd tried to teach their informants to count. Thus, for example, Lloyd noted in December of 1871 that: "//Kabbo counted to ten, without help for the first time."72 Bleek also drew little sketches on the left hand pages of his notebooks to assist informants in identifying objects - a ring, an ear, an eye, a moon, a bow - or, a little more abstractly, large and small images to impart a sense of scale, or sequences of moons to represent waxing or waning.73

The sense of importance the researchers attached to their notebooks may have differed initially. Lloyd's first three notebooks are slender exercise books for jottings, in marked contrast to Bleek's bulky volume with a beautiful cream cover. In January 1871, however, Lloyd copied out pretty much word for word the words and sentences contained in her exercise books into a more serious brown hardbound notebook.74 This copying out exercise suggests perhaps that her involvement in the project in the early days was seen as tentative and experimental, but as the value of her work become obvious, she converted it into something more formal.

We have a better idea of how /A!kunta viewed the notebooks. Numerous incidental remarks suggest that the writing process was almost as curious to him as Bleek's beard. The researchers record him commenting variously on the drying of ink, the shadow of the recorder's hand and, on a number of occasions, on the process of writing.75 On the 14th of September, for example, Bleek has /A!kunta saying: "thou writest, I do not write." He then notes a series of performative events (a theme which I will develop later): "turn round, I turn round, she [i.e. Lloyd] turns round, it turns round, thou turnest round," [my parentheses] and then /A!kunta reflecting back on the writing process: "thou has written." About a week later, he records /A!kunta saying: "paper, thou writest", to which he responds: "I write a book." It is interesting that this sense of self-reflexiveness about writing and recording is absent from Lloyd's notebooks, despite the fact that they are fuller and more detailed. This may well reveal that /A!kunta had begun to internalise a sense of Bleek as the more serious scholarly presence,76 a sense no doubt encouraged by Lloyd's frequent deference to Bleek's judgement in these early days. The margins of her notebooks feature regular comments like: "must ask Wilhelm", "W. thinks not ... here", "... apparently which I must mark by "Wilhelm says the click "W.: I should have said ..."77

It is also of some interest that Bleek sometimes took on the voice of first person narrator. This is something that very seldom occurs in the sentences recorded by Lloyd. It is an indication of his greater linguistic competence and confidence at this stage, but again also perhaps of a more assertive presence in the recording process. There is a contrast, on my reading, between Bleek's more researcher-driven vocabulary and Lloyd's more fluid and informant-driven notes in these early days. This was presumably also related to the power relations that were an intrinsic part of the recording sessions. Perhaps the simplest way of illustrating this is with reference to the contrasting terms that /A!kunta used to refer to the two researchers. Whereas Bleek was referred to as "baas" (in the original /Xam record as well as in translation), "mynheer", "master" (with Jemima Bleek as "missis"), and, rather oddly at one point, "magistrate", Lloyd was known much more familiarly as "Miss Lucy" or "nooi".78 The more open relationship that /A!kunta had with Lloyd undoubtedly accounts for the richer, more flowing nature of her early record. It was not coincidental, for example, that /A!kunta first sang in front of Lloyd, when Bleek was not around. But more of that later.

Learning by pictures

The obvious starting point in attempting to understand the complexities of the learning encounters in the Mowbray home is the absence of a common language. Bleek spoke German, English, presumably French (given that sundry volumes in his library were in French) and inscriptions in the books in his library suggest that he had a reading knowledge of numerous other languages. Lloyd spoke English and German, and evidently had a reading knowledge of Italian and French. /A!kunta spoke /Xam and may have picked up just a smattering of English from school lessons, prayers, and interactions with white convicts at the Breakwater Prison.80 He also spoke a version of the Cape Dutch language that would later be described as Afrikaans. It was this that served as the initial language of communication, although neither Bleek nor Lloyd appear to have been too adept at it (in written form at least).

The linguistic gulf necessitated the use of props to aid communication. Visual images were the most obvious resource. Bleek's doodle-sketches have already been mentioned and it is evident from the vocabulary recorded that children's picture books were also used extensively in the early weeks. When Lewis-Williams claims that "/Xam words were ... elicited by pointing to pictures in little Dorothea's and her elder sister Edith's books,"81 the unreferenced source is Dorothea Bleek quoted by Rosenthal:

He [Father] used to take children's picture-books, including some of mine, in which common objects were reproduced. To these he would point - trees, men, rivers, or whatever else the illustration happened to show. The Bushmen would click out the word in question, which father would then write down with the aid of a phonetic code he himself had invented ...82

The difficulty with this evidence is that Dorothea was some years from conception when the technique of pointing to pictures was adopted, and then primarily by Lloyd rather than Bleek, a romanticised father figure that Dorothea never got to know (she was two when he died in August 1875). So either Rosenthal misquoted her, or the old lady was fibbing. The children's picture books must have belonged to Edith, who was certainly of a reading age. The only book that Tanya Barben has been able to trace as having belonged to her at the time is J.Aspin's Ancient Customs, Sports and Pastimes of the English (London, 1835),83 but its neat sketches of midsummer commons and Guy Fawkes gatherings would have been singularly unsuited to any object recognition by /A!kunta.

More fruitful for our purposes is the work that Lloyd did with /A!kunta using pictures from travel narratives. It is interesting to note that Bleek's notebooks show no record of such interactions, suggesting that he entrusted the work of accumulating vocabulary to Lloyd. She referenced the travellers in abbreviated form in the margins of her first two notebooks, again with characteristic diligence: "Fr." for Gustav Fritsch, "Th." for George Thompson, "Le V." for Francois le Vaillant, and "Licht." for Heinrich Lichtenstein. Accompanying entries to specific volume and page numbers, as well of course as the nature of the vocabulary recorded, allows one to trace the precise editions that Lloyd worked through and then read the recorded vocabulary alongside the images in these travel volumes.

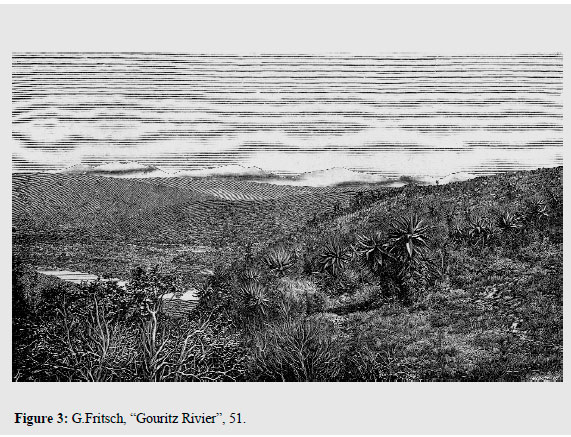

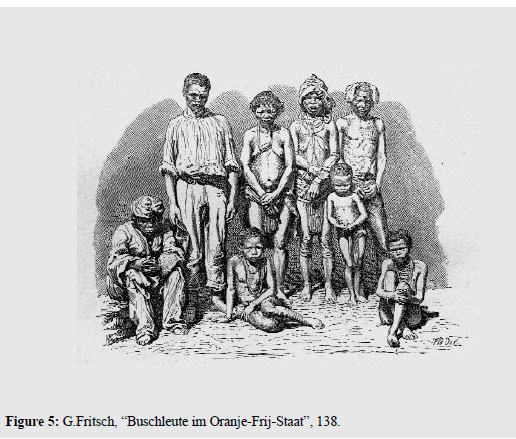

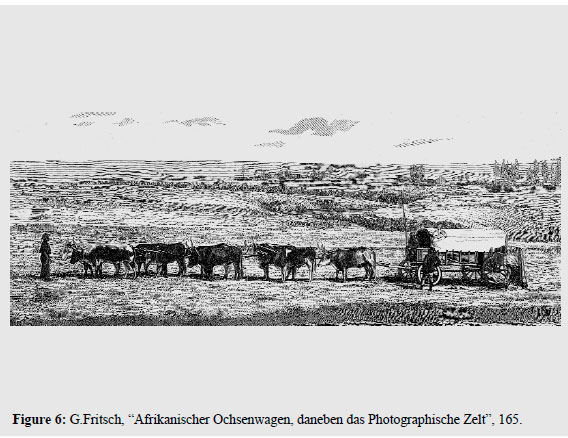

Lloyd began on the 1st of September with Gustav Fritsch's Drei Jahre in Süd-Afrika. Her choice was probably not coincidental. The visuals in this travel volume were worked up from high quality photographs taken by Fritsch in the field and provided a degree of realism that contrasts markedly with an older tradition of travel illustration, exemplified say by the illustrations in Le Vaillant's travel narratives.84 The eclecticism of Fritsch's early interests during his travels, which I have discussed elsewhere,85 also meant that there was a broad range of visual subject matter spread over 75 illustrations. The exact copy that Lloyd and /A!kunta used is now kept in the African Studies Library of the University of Cape Town, to which it was donated by Dorothea Bleek in 1947. It is an impressive book, bound in a now faded blue with its title embossed in gold print on the front cover. It was almost certainly acquired by Bleek during the family's visit to Berlin in June and July of 1869. The book had only been published the previous year and Bleek's letters indicate that he met up with colleagues and mentors like Lepsius. He certainly knew Fritsch well, for as early as 1863 the photographer-anthropologist had spent three months reading in the South African Public Library, Bleek's place of work, before setting out on his travels.87Fritsch's inscription in the volume suggests that relations between the two scholars were warm: "Seinem verehrten Freunde, Herrn Dr Bleek, freund-schaflichst gewidm. v. Verfasser." ["Dedicated by the author to his esteemed friend, Dr. Bleek."]

Lloyd's method was to go through the images in the travel volumes from beginning to end rather than say pre-selecting images of Bushman life which may have seemed most likely to elicit a response. An illustration on page 330 of Fritsch's narrative, for example, shows a scene of Kalahari Bushmen hanging up slices of ostrich flesh to make into biltong. Their activity, clothing or adornments - like karosses and beads - may have been deemed a potential source for new vocabulary, or even ethnographic information. In the event, Lloyd neither started with this image nor, oddly enough, did /A!kunta have anything to say about it.

To my mind, the most striking general feature of Lloyd and /A!kunta's work with travel narratives is the off-centre nature of interpretation, and the many examples of partial recognition or misrecognition.88 The notion that the encounters between the researchers and their informants sometimes involved misunderstanding and, most of the time, negotiation and grappling is rather at odds with an existing image of the texts as having a fixed or even mystical kind of aura. The metaphor of the "Rosetta Stone", employed by Biesele in a surprisingly sparse introductory comments to a recent re-issue of Specimens of Bushman Folklore, seems to reflect such assumptions, as say does her reference to these as "the exact words of an extinct people."89

What then did /A!kunta comment on? The landscape view of the Gouritz River in the Eastern Cape (shown below) elicited recognition of "aloes, the boom sticky, prickly, goey inside" in the foreground.90 /A!kunta perhaps had the fleshy aloe-like parts of a quiver tree in mind, as riverine aloes were not a feature of his home environment around the Strandberg. In another landscape scene the only recognisable detail is a little sprout of "pointed grass" in the foreground. This is hardly surprising. The visual codes of the landscape tradition, whether in paintings or travel narratives, were completely alien to the visual codes of San rock art with which /A!kunta would have been familiar. The subject matter also differed. The rock art of the Strandberg, which is less developed than one might anticipate given the prominence of this site in the records, depicts animals rather than plants: gemsbok, ostriches, some beautifully crafted elephants and (on my reading) a giraffe.91 There are no images of human figures or plants or quiver trees of the type encountered at Springbokoog, some 50 kilometres to the south.92Moreover, the actual landscapes depicted in Drei Jahre were radically different from the flat, arid terrain of /A!kunta's home. Riverine vistas, Drakensberg kranzes or the densely forested kloofs of the Witels may have impressed German readers with their sense of grandeur, but were evidently completely unrecognisable to a "Flat Bushman".

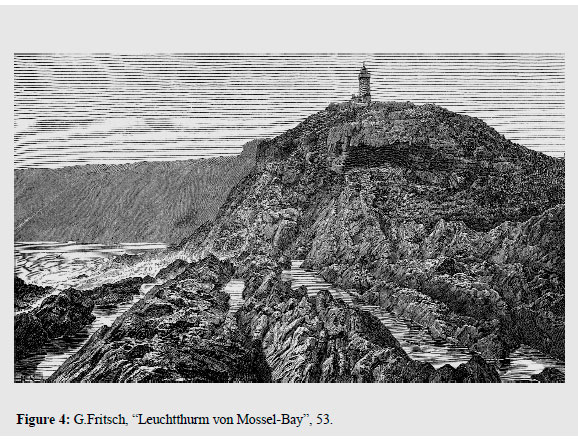

This image of the lighthouse at Mossel-Bay prompted the response: "rocks (kilip)". Lloyd's misspelling of the Afrikaans word "klip" (stone) is the norm rather than the exception in her notebooks. Her knowledge of Cape Dutch was only partial and it is probably fair to say that the words in Cape Dutch (of which there are many, perhaps over a hundred) were typically misspelt. But she did have a fine linguistic ear and "kilip" may have been a closer phonetic rendition of /A!kunta's pronunciation of the word at a time that obviously predated any standardisation of Afrikaans spelling. She then records: "does he mistake it for wood." Since /A!kunta's words (other than "kilip") are not recorded, we can only guess at how she came to this view. Did he perhaps point to some other wooden object in the study, like Bleek's ruler? Or is it perhaps a projection of her own sense of the overly smooth woodenness of the rocks in this picture?

Another off-centre recognition is of the picture showing a group of Bushmen that Fritsch photographed on the Free State farm of an English settler.93/A!kunta's attention, Lloyd records, was drawn to the child seated in the centre and the "chain on neck of Bushchild". Here, as in many other cases, it is difficult to establish the precise correspondence between the /Xam version that /A!kunta gave and Lloyd's interpretation of what he was referring to. We can only guess at the reasons for /A!kunta picking out what is scarcely identifiable in this image as a chain - it may as easily be a necklace. Was it not because chains had particular resonance for a young man recently forcibly captured, and transported to a gaol in Victoria West and then incarcerated at the Breakwater Prison where long term prisoners still worked in "chain gangs"?

The coercive nature of /A!kunta's arrest and of social relations in his home area, may also account for his picking out of a "whip" from the range of objects in this well-known image of Gustav Fritsch standing next to his ox-waggon and photographic "tent". /A!kunta also identified "wagon, wagon whil", which had become increasingly familiar sights in his native landscape.94 Other references in the notebooks give a more precise sense of his relationship with the owners of wagons and whips. On the inside cover of her first notebook, Lloyd records: "Stormberg (3 days from Kenhardt and 10 from Cape Town ... Piet Swart, the farmer's name whose ..." [on whose property?] "he Stoffel lived in Bush-house with springbok skins over it." His farmer-employer evidently assisted in his arrest: "Piet Zwart he fang for me, he bring de Fiel Kornet his place," and there is explicit evidence to suggest that /A!kunta was afraid of this man. After almost three months at the Hill, he is recorded as saying: "I do not fear him ("Ik cannie mehr bane nie" (abt. Piet Swart) ..." ["... I am no longer scared of him" (abt. Piet Swart) ..."]. And later: "Ons Bushmen rechte ban vor (or von) de Boer" ["We Bushmen are really scared of the Boers"].95

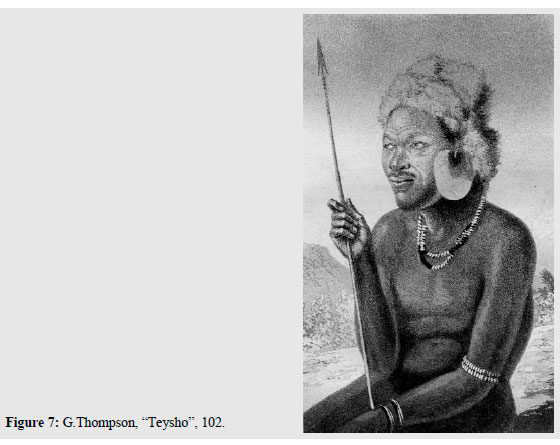

On the 2nd of September, Lloyd worked through George Thompson's travel narrative, published in 1828. The exact copy has gone missing, but the edition may well have been one inscribed by the author as he was Bleek's agent in London.96 Bleek was evidently present at this session as marginalia in Lloyd's notebook reads "WB". A picture of an "aardvark" prompted some rare though sparse, additional commentary: "very good food" and a gesture expressing love for this animal: "sigh, to, S. translates it 'heart to stand.'" Two double-page colour illustrations of animals also elicited response. The "hartebeest" on the fringes of one illustration were evidently more immediately familiar to /A!kunta than the "Gnoo & Quagga" (Thompson's title) appearing in much larger form in the foreground. A similar scene later in the volume led him to identify, hardly surprisingly, a "springbok", but also "koodoo (S. has not seen, but the old Bushmen have told him about it)."

He also commented on this portrait of a Tswana chief. The head-and-shoulders portraits in Fritsch's travel volume, which had been reworked from his photographic "gallery" of African chiefs,97 had struck no visual cord with /A!kunta. Again such stylised representations of a chunk of the human body were completely alien to modes of visual representation in rock art. Here /A!kunta commented: "The man is great (man is roep)" and pointed to "arm ring, arm-ring (bracelet), necklace, spear with a long stick or handle ... " What strikes me here is not so much the object recognition or Lloyd's additions (eg. bracelet?), but the interpretive sense of the message: the status of the chief. Was this influenced in any way by his contact with Koranna chiefs at the Breakwater ("the Korannas have two captains... the captain is great")?98 Again though it is difficult to know exactly how Lloyd derived the English version, as the Cape Dutch "roep" means to "call" rather than "great".

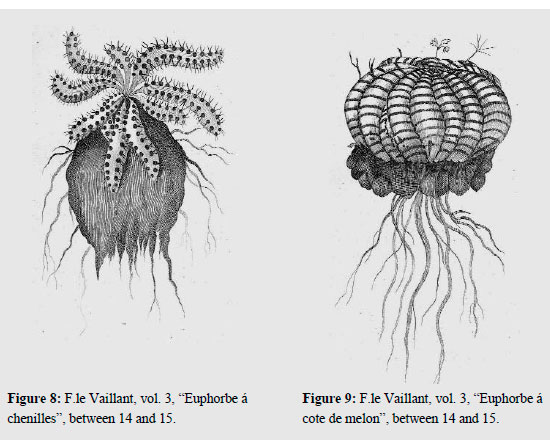

Having parted ways with the travellers for some days and worked mainly with children's picture books and something identified on the left hand page as "my book on monkeys",99 Lloyd took up further travel volumes on the 8th of September. She began with a three-volumed French edition of Francois le Vaillant's Second Voyage dans l' Interieur de l' Afrique, published in Brussels in 1797. Le Vaillant's travels appeared in many guises and tongues, but the page references to illustrations pin it down to this edition. The volumes are sparsely illustrated, which is surprising in view of the author's own prodigous pictorial output.

What did prompt recognition, and in one case spectacular misrecognition, were these detailed drawings of plants. The picture of the "euphorbe á chenilles" elicited more information that any other image shown to /A!kunta: "It is by the 'grote rivier' S. says and that the Bushmen use its poison. 'de giff' (Boer's name), /ggoaken (or !?) (Bushman name), #xau (also Bushman name), /ku (also Bushman name)."100 The "Grote Rivier" referred to here and later by other informants is the Orange River, over 150 kilometres north of /A!kunta's home. In the case of the "euphorbe á cote de melon", Lloyd recorded: "Euphorbia, striped he calls inquiringly D'heouw."101 Later vocabulary reveals that "D'heouw" (or more accurately "dou") refers to a zebra!!102 The fact that /A!kunta could, albeit "inquiringly", suggest that this unusual plant looked like a zebra is a marvellous illustration of the possibilities of "ethnographic misunderstanding" in a context where the informant's visual world was so radically alien to that of the European genres to which he was being exposed. And, as I have noted, there was initially little in the way of a common language that could mediate between these two traditions.

On the 10th of September, Lloyd took up the original German edition of Lichtenstein's Reizen in Südlichen-Afrika, published in Berlin in two volumes (1811 and 1812). Here too the volumes in the African Studies Library at the University of Cape Town are probably the very copies once held by Lloyd and /A!kunta, for the date of acquisition stamped at the back (17 June 1940) corresponds to the period when Dorothea Bleek began to donate materials from the family collection. Lichtenstein's Reizen had already been used extensively by Bleek. A record of some 132 Bushman words and their translations were among the only snippets of information about the language before Bleek spent a month working with Adam Kleinhardt in the Breakwater Prison in July 1866.103 It also features a short list of sentences, in which the envisaged informational exchange rather crudely reveals Lichtenstein's motivations:

Wo kommst du her? ["Where have you/do you come from?"]

Ich komme dort her. ["I came from there."]

Wie hiesst du? ["Who are you?"]

Ich bin ein Colonist. (Europaer, Weisser). ["I am a colonist. (European, white man)."]

Hast du Wild gesehen? ["Have you seen game?"]

Ja, Nein. ["Yes, No."]

Wo hast du es gesehen? ["Where did you see it?"]

Wo gehst du hin? ["Where are you going to?"]

Gib mir Tabak. ["Give me tobacco."]

Ich habe nicht. ["I have none."]104

Lloyd's interests, however, were with the pictures. She may have selected Lichtenstein because of a prominent image of men on horseback, in an attempt to elicit some reaction from /A!kunta. A well read liberal like Lloyd, who had been resident in Natal and the Cape for almost 20 years, would have been well aware of the history of the commando system and the intense debates that they had generated. A!kunta's response to the picture was simply "banie mens te ride" ("many people riding").105

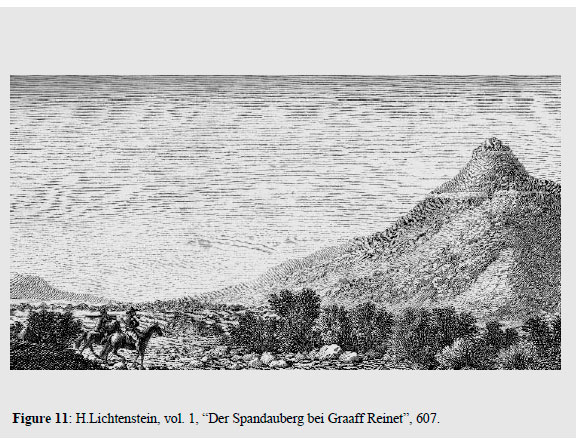

The same volume also features the one landscape scene that did evoke more sense of recognition. This illustration of the Spandauberg near Graaff Reinet prompted /A!kunta to comment: "stones, trees, mountain..." Even this limited degree of recognition was perhaps because this image bore the strongest resemblance to /A!kunta's home territory, which was also very dry with small rocks and shrubs, and an imposing mountain in the form of the Strandberg.

A grammar of performance

The recording sessions in the first two weeks then, involved much pointing at pictures by Lloyd. Her vocabulary in these early days was confined to words rather than sentences. Bleek's earlier exposure to the language and prior philological training account for his ability to work with more complex constructions, notably sentences expressive of grammatical form. It is not surprising then that it is in his notebooks that we read of what I term "a grammar of performance", which represented the second phase in the learning process.

My emphasis here on performance rather than text is in keeping with a now very well established body of work. Scholars in the field of African oral literature, from Finnegan and Scheub in 1970s to the remarkable work on Yoruba oriki by Barber, praise poetry by Vail and White and historical narrative by Hofmeyr in the 1990s, demonstrate that oral communication can only properly be understood in performative context. In certain cases, notably the oriki forms that Barber analyses, it is almost impossible to make much sense of these traditions other than as performance.106 So too in studies of American folklore, as Guenther notes, there was a move in the 1970s and 1980s to an emphasis on "the performative event".107

Although my interest here is not in oral performances explicitly conceived as such - //Kabbo's more consciously crafted stories were a later development - the methodological shift away from what can be read on a page to a sense of fluid and contingent communicative events has influenced my thinking. For while a collection of "words and sentences" (as Bleek would later classify them in his official reports)108 may on first reading seem unfruitful terrain for the application of "performance theory", if we study the notebooks closely they read as nothing so much as a dramatic script. The voices and alternation of speakers (and therefore perspective) may be pieced together with careful attention to detail, tone or content.

Some sense of these performative qualities comes through in the Bleek sisters' recollections. The much quoted passage reads:

At first his [their father's] chief medium of communication with them [his informants] was the broken Dutch they understood and spoke. But that did not go far in exhausting person and number, mood and tense, not to speak of the finer shades of meaning. So to check what he had set down and add to it, he resorted to acting the words, or making the Bushmen act them. He used to call me in to assist in getting plural and dual, exclusive and inclusive. It was amusing to stand and sit, walk and run, hop and jump, or watch the Bushmen performing these antics at word of command.109

Here again though the "memories" need to be read with great caution. The paternalistic vision of the informants "performing antics" at their father's "word of command" is at odds with the more complex and sensitive set of relationships that one reads of in the notebooks. The "me" referred to in this passage can clearly not be Dorothea, as Lewis-Williams suggests, as she had not yet been born.110 So we can only assume that these are Edith's memories, written up here by Dorothea. Even this common sense reading may be an oversimplification, however, for the history recounted by the Bleek sisters leans so heavily on material traces available to them forty years later that it is difficult to know what was remembered and what refashioned in light of objects in their surroundings. Thus, for example, references to the meditative character of //Kabbo may well simply have been read from a photographic portrait. Comments about musical instruments made by informants echo, almost word for word, manuscript notes made by Lloyd in 1873 and accessible to Dorothea in 1911.111 Likewise, the "memory" cited above of Edith "performing", I read as a retrospective piecing together by Dorothea based on the evidence contained in the notebooks in her possession.

This was, after all, precisely the time when Dorothea was actively working with the notebooks to assist Lucy Lloyd in getting materials ready for publication.

The extract above may even have been based specifically on the following record from Bleek's first notebook. The setting is seemingly an evening meal on the 14th of September with at least six people present: /A!kunta, Lucy Lloyd and the four members of the Bleek family (Wilhelm, Jemima, Edith and Mabel). A sequence of sentences with /Xam translations is what appears in the notebook; the scripting is my own:

Wilhelm Bleek: "I give her flesh, I give my daughter flesh" [i.e. meat]

Edith Bleek: "I give my father meat"

Lucy (or another) to Edith: "Thou givest thy father meat"

Probably /A!kunta (given the grammatical error) to others:

"She give her father meat"

Lucy (or perhaps Wilhelm) to Edith: "Thou givest thy mother meat"

Edith to others: "I give my mother meat"

Probably /A!kunta (again, given the grammatical error) to others:

"She give her mother meat"

Lucy (or another) to Edith: "You give your mother meat"

Edith (suggesting Mabel was also present): "We (excl.) give our mother meat"

Lucy (or another) to others: "They give their mother meat"

Wilhelm to others: "I give my wife meat ..."112

A few comments are in order here. Firstly, the cast of characters featured in the notebooks clearly extended beyond the two researchers and their informants. There is much evidence of inscriptions in a wider domestic context elsewhere - in the form say of references to Jemima Bleek breastfeeding Mabel, Mabel crying when her teeth push through, or Edith bringing a dry pod of seeds into the house.113 Secondly, shifts of speaker are typical of the early record of "performative events" in both Bleek and Lloyd's notebooks. If we read the notebooks closely, we can imaginatively follow the informants and the researchers as they move in and out of the house, or variously sit and stand in recording sessions, or play with various objects in a room. There is a kind of spontaneity that evokes a much livelier sense of communicative interaction than that suggested by Guenther (though he is referring to later "story-dictation" sessions, which were undoubtedly less fluid).114

About a fortnight later, Bleek recorded the following interaction. Again I have added the scripting:

/A!kunta to Lloyd: "I make a bow, I make arrows, he [i.e. Bleek] was angry with me"

Lloyd to Bleek: "Thou wert angry with him"

/A!kunta to Lloyd and Bleek: "I shoot with the bow"

Lloyd to /A!kunta: "Thou shootest with the bow"

Bleek to /A!kunta: "Thou shootest me with the bow"

/A!kunta to Bleek: "I shoot thee with the bow, thou hast fallen" (been killed crossed out)

Bleek: "I have fallen" (been killed crossed out)

Lloyd to /A!kunta (or perhaps vice versa): "He has fallen, he is dead ..."115

Bleek's "anger" was staged in this instance, but there are other occasions when he did genuinely seem to be angry with /A!kunta.116 Such moments provide glimpses of the unequal nature of power relations between Bleek and his informant. Guenther suggests that there must have been "elements ... of wariness, distance, self-consciousness, servility" in the attitudes of /A!kunta, and then //Kabbo, towards their "hosts-cum-parole officers",117 and the notebooks bear him out. Quite apart from the terms of deference that /A!kunta used to refer to Bleek, he was their domestic worker as well as their informant - even if his chores were not particularly onerous. There are incidental references to him cleaning mats ("ik uitslang de mats de grond"), carrying a wine basket ("banie schwer") and building a bush house for the family cow or cows.118

Bleek later wrote that he was forced to hire "a casual hand from the village" in cases where "a man's strength" was required.119 The former prison warder was not of much use in this regard. A crossed out section of a draft letter reveals that "the white man whom I had in charge of them [?] was very respectable and steady, but so sickly that he could not do much work either and whilst he was here I had usually to get other help for work in the garden and even chopping wood."120

A man named Karl was probably one such "hand from the village". He only appears in Lucy Lloyd's notebooks, suggesting a day time presence at the Hill. He is first mentioned on the 20th of September in a series of sentences about "beating", a very strong theme in /A!kunta's early communications and one which hints again at coercive social relations in his past: "Thou beatest them all, thou beatest me, I beat thee, I beat Karl, I beat Mary and Annie." (I have not been able to work out who Mary and Annie were. They may have been cooks or domestic workers in the Bleek-Lloyd house at the time.) A!kunta continues: "Karl bring it yester avond, he takes it today." A fortnight later, Karl resurfaces and in a way that suggests a kind of bond of sympathy and equivalence in his status in the household. /A!kunta is recorded as saying: "I come, I come and ask where is Karl ... I ask him if he is ill? I ask him does he hunger? He asks me if I am cold?"121

Then on the 1st of November, there is a reference that simply leaps out at the reader of the notebook: "he is sorry..., we 'loep in de kleine katt de water'" with an explanatory note on the left hand page: "describing himself and Karl drowning the kittens." Why /A!kunta and Karl drowned (the Bleek family's?) kittens will of course remain a mystery. It is very tempting to read this as an act of resistance by /A!kunta, still very much under guard, and his footloose accomplice Karl, but the sense I get from the "words and sentences" that make up the interactions between /A!kunta and the researchers at the time is not one of resistance or anger, but of fragile beginnings in the establishment of bonds of understanding and sympathy, of a more protective environment nurturing some feeling of security in a very traumatised young man. Perhaps the drowning of kittens was Karl's initiative. Later sentences hint that he may have got fired for his cruelty: "Karl is weg, the ander man he sall come" (16 November), but then was reemployed: "(Carl is) good to the little cat." (24 November)122 Thereafter Karl disappears from the records.

Another "performative event", recorded about two months later, hints at how /A!kunta's unequal status was inscribed in the very process of linguistic acquisition. The setting is probably the study with Bleek, Lloyd, /A!kunta (and I have to assume Jemima Bleek) present. Bleek begins by eliciting /Xam terms for sexually explicit vocabulary: "genitalia (feminina), genitalia (masculina)" (vulva and penis crossed out) - and then continues:

Bleek: "exerceo coitum" (I have sex, literally I exercise sex)

Bleek (with reference to his wife?): "exercet coitum" (she [/he/it] has sex)

Bleek (again with reference to his wife?): "exerceo coitum cum ai" (I have sex with her)

Here Bleek adds: "he [i.e. /A!kunta] cannot be drought [i.e. brought] to say this of the person he addresses!" [to Lloyd? to Jemima?]

Bleek: "exercet coitum mecum" (she [/he/it] has sex with me)

Bleek: "exerceo coitum (in order to) beget a child" (I have sex ...)

Bleek: "exerceo coitum cum ea so that she may beget a child" (I have sex with her ... )

Bleek: "exercet coitum mecum so that she may beget a child" (she has sex with me ...)123

This series of entries stands out as the only Latin recorded in the notebooks, apart from scientific versions of animal names taken down after visits with informants to the South African Museum. Exactly what the performative event involved here does give one pause. Other vocabulary relating to the naming of sexual parts, which Bleek had already begun to garner during interviews with Adam Kleinhardt in 1866, I assume to have been elicited with the help of visual aids, perhaps an anatomical text. This clearly would not have sufficed in this instance and perhaps some gestures were necessary to get the message across. The fact that /A!kunta could "not be brought to say" the sentence "I have sex with her" (to Lloyd?) is a poignant illustration, not only of the young man's discomfort at such sexually explicit vocabulary, but of the implicit coercion involved in this interaction - in the sense that Bleek clearly tried to get him to say this.

It is also of course highly revealing that Bleek felt it necessary to record these interactions in Latin, the academic language of his Ph.D. and some of the older works in his library. He may even have borrowed the practice from books that he had read. It was evidently not uncommon. A British medical journal complained at the time of one such author who tried to "veil" sexually explicit passages "in the decent obscurity of a dead language."124 We can only speculate as to Bleek's reasons for doing so in unpublished notes. Perhaps he (quite rightly) anticipated that his notebooks would one day become a public record. It may also have been a sense of prudishness on his part, although this seems less likely in view of his doggedness in extracting sexually explicit terms from virtually all of his informants.

Songs and Fables

There is evidence of other types of performance in these early months. Lloyd recorded the words of a song that /A!kunta sung to her on the 3rd or 4thof October:

n ga mama kowki hi,

tei /ku //kang a,

n ga mama kowki hi, tei ku //kang a,

n ga mama /ku //kanga

n ga mama /ku /kanga

kowki hi, tei /ku

//kanga

nga mama /ku //kanga

hing kowki hi

tei /ku //kunga.125

The repeated references to "mama" indicate that this was a song about his mother and translated fragments suggest that its theme was hunger: "'he [she?] banie hungry, he cannot eat, will nie coss nie ... she cannot eat, he seen de ander frau, he is eat, he cannie eat nie.'" On the following day, Bleek recorded /A!kunta saying: "I sang a song yesterday, I sang of my mother" and later: "she [i.e. Lloyd] heard me sing." He evidently got /A!kunta to repeat the song, as he also provides a /Xam version of it and one which differs somewhat from Lloyd's. Here the translation is clearer: "my mother (can)not eat, (she) lies with hunger, when she say ... she not eat, when she say, she, she is hungry."126

/A!kunta repeated this lament to Lloyd on the 25th of November and sang it to his father and grandparents as well. /A!kunta explained:

Ik sing, ik screit die mamma

Ik sing, ik screit die mamma

Ik sing, ik screit die mamma

I sing my father

I sing my mother's father

I sing my father

I sing my "oud tata"

I sing my grandfather (here father's father)

"Oud frau, ik sing" (grandmother)

When asked if the song could be applied even more widely, he replied : "I sing my mother's mother, my brother, my sister ..."127

Whether or not these songs were accompanied by sounds from a musical instrument is difficult to establish. There is reference to /A!kunta making "bows" at the time he first sang, which may have applied to a musical bow as well as the hunting bow referred to in an earlier extract. A few days later, Bleek recorded the vocabulary: "//ha - goura (playing bow) musical instrument",128 though this may have been identified from a picture rather than an artefact that /A!kunta had made. Manuscript notes written by Lloyd some years later recount in some detail what this instrument was and how /A!kunta might have played it:

I. //ha, a musical instrument in the form of a bow, played among the Bushmen by the male sex only. The piece of quill, to which one end of the string is attached, is taken from the wing-feather of a 'Korhaan' ... The piece of quill is applied to the mouth of the player who draws long breaths through it, and accompanies the sound thus produced, by a grunting kind of noise, as well as, sometimes, by singing ...129

Another mode of performance was the re-enactment of folktales. Bleek's earlier involvement in folktale collection is rather obscured in a scholarly literature which tends to bracket off his "Bushman period". Thornton is, in my view, the only analyst who appreciates the extent of continuity between Bleek's earlier intellectual projects and his work with the /Xam. As Thornton demonstrates, the collection of /Xam folklore by Bleek and Lloyd in the early 1870s was a continuation of years of reading, collection and publication of texts by Bleek, prompted initially by work done in New Zealand by George Grey.130 As noted earlier, the shelves of Bleek's library at the Hill featured numerous volumes of folktales, including compilations of Native American and Maori tales.131

One concrete example of this continuity is the attempt by Lloyd and Bleek to draw /A!kunta out by recounting "fables" from Bleek's earlier collection of "Hottentot Fables and Tales", which was published in London in 1964 under the title Reynard the Fox in South Africa. On the 16th of November, Lloyd recorded on the left hand page of a notebook: "An attempt at fable p. 57 of 'Hottentot Fables and Tales'". The reference is to a tale entitled: "A Woman transformed into a Lion", taken by Bleek from James Alexander's Expedition of Discovery into the Interior of Africa (1838). The beginning of the tale as its appears in her notebook ("Once upon a time a certain Hottentot was travelling in company with a Bushwoman, carrying a child on her back") is taken word for word from the published text, but this is followed by reformulations of the text into short sentences or phrases, each of which represents a scene: "he fatt die pat, they fatt die path, carries child on back, (they) walk far, they see quaggas."132Given that /A!kunta had little knowledge of English, it is fair to assume that "the Hottentot" taking the path, "the Bushwoman" carrying the child on her back, and their sighting of quaggas would have been conveyed by Lloyd at least partly through bodily movement and gesture. /A!kunta then provided a /Xam translation of the scenes which Lloyd recorded. What we have then is the rendering of an already published "Hottentot Fable" into the /Xam language rather than tales originally told by /A!kunta in Dutch as Bleek was to report.133

The following day Bleek worked with /A!kunta through "Tale No. 26 Bushmen Fables". His heading refers to a story entitled, "The Lion and the Bushman", again taken from James Alexander's travel narrative. These two tales were selected as they were the only ones out of a collection of forty-two that feature Bushman protaganists. Most of the others are stories of animals and their antics, ordered by species. In Bleek's notebook there is no evidence of the kind of interlanguage used by Lloyd, though the flowery formulations designed for Victorian readers are rendered in plainer English. The published version of the tale begins somewhat verbosely: "A Bushman was, on one occasion, following a troop of zebras, and had just succeeded in wounding one with his arrows, when a Lion sprang out from a thicket opposite, and showed every inclination to dispute the prize with him." The notebook version reads: "a Bushman hunted zebras, the Bushman shoots it with the arrows, wounded (killed it), a lion jumps out of the wood, he climbs the tree ..."134 Again, it is fair to assume that Bleek would have had to act out successive scenes, beginning with the hunt and the lion climbing the tree, to convey this sequence of events to /A!kunta.

Conclusion

One way of reading this article is in terms of two general arguments. The first concerns early learning. I have sought to piece together the logic of the learning process as it unfolded in Bleek's study during September, October and November of 1870. The absence of a common language or any substantial prior research materials on Bushman languages meant that Lloyd, Bleek and /A!kunta had to start pretty much from scratch. They began with pictures from children's books and travellers accounts, and I have followed in some detail /A!kunta's responses to the illustrative materials in the travel volumes of Gustav Fritsch, George Thompson, Francois le Vaillant and Heinrich Lichtenstein. My emphasis here was on the degree of misunderstanding in these encounters between radically different languages and systems of visual representation.

The second phase of the early learning process, which I date from mid-late September, involved various perfomative events. Bleek's (evening) sessions with /A!kunta, Lloyd and often a much wider cast of characters, were typically structured grammatical performances with constant shifts of speaker and perspective. They allow one to piece together a vivid sense of the changing texture of the relationships between /A!kunta and the researchers. In addition, there is evidence of other types of performance: /A!kunta singing to Lloyd and then Bleek and being prompted to provide /Xam translations for re-enacted scenes from "Hottentot tales" collected and published by Bleek in the 1860s.

The second argument relates to the reading of evidence. I have attempted to highlight the complexities of reading evidence about Bleek and Lloyd's project. Given the investments - personal and ideological - in reconstructing a project that produced such unique products, we have to be particularly alert to the interpretive layers, and at times fictions, that have been manufactured after the event. The well mined "memories" of Edith and Dorothea Bleek, I have suggested, were probably at least partially invented by Dorothea in 1911 on the basis of her rereading of notebooks and other extant evidence like photographs, manuscripts notes, or ethnographic artefacts. Even their character sketches, brief as they are, which have been uncritically recounted by Lewis-Williams,135 ring peculiarly false when read against the evidence recorded in the notebooks by Lloyd and Bleek at the time. Memories say of /A!kunta as harmless but "conceited", "strutt[ting] about with the gait of a finished dandy"136 bear little resemblance to the lonely and vulnerable young informant that we encounter in the notebooks.

The article that Eric Rosenthal wrote on the basis of an interview with Dorothea Bleek in the 1940s needs to be read, if anything, with greater circumspection. Rosenthal's account is filled with paternalistic stereotypes of the "strange servants" in the Bleek household, and romanticisations of "the Doctor" and his daughter. Lucy Lloyd's contribution is reduced here simply that of a helpmeet.137 As I have argued above, the "memories" he quotes of Dorothea having her picture books used in early interactive encounters, acting out mood and tense with informants or putting her "flexible young tongue" to clicking ends must simply be read as fictive reconstructions.138 She was some years from conception when this early learning took place.

Scholarly accounts of context are (with very few exceptions) surprisingly poor. This is not for lack of "primary materials" to work with. It may be pre-sumptious of me to speculate about the motives of other scholars in the field, but I read this comparative lack of interest in context as a function of attitudes to text. The actual words of the texts published in Specimens of Bushmen Folklore in 1911, and republished in 1968 and in 2001, and in a growing number of selected collections, certainly have a kind of seductive charm. They do, as Skotnes suggests, impart a sense of a radically different world with a different sense of time and space.139 So, at one level, they do "speak for themselves" and this perhaps has led to a keeping at arm's length of the taxing work involved in reconstructing the changing communicative events and settings within which they were produced. We are told something of the recording process, given precis biographies of informants and researchers, but very little else. I could not therefore disagree more strongly with Alan James' view in the opening line of what is still a very fine book that: "Such has been the flowering of interest in Bushman, or San, society and expressive culture over the last twenty years, that a collection of renderings of /Xam narratives requires little in the way of general introduction."140

1 I am most grateful to Lesley Hart, Isaac Ntabamkulu, Yasmin Mohamed and Janine Dunlop at the Manuscripts and Archives Department of the University of Cape Town for creating quite the most warm and enabling research environment that I've ever had the pleasure to work in. Thanks also to Tanya Barben of UCT library's Special Collections Department for her energetic (and very successful) efforts towards reconstructing Wilhelm Bleek's private library, to the marvellous staff at UCT's African Studies Library especially Steven Herandien for scanning the visuals. I have also lent on Karin Ström for her expertise at following up property records and architectural plans and Richard Whitaker for translations of Latin. Thanks to you both.