Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

Kronos

versão On-line ISSN 2309-9585

versão impressa ISSN 0259-0190

Kronos vol.27 no.1 Cape Town 2001

Anthropology and portrait photography: Gustav Fritsch's 'natives of South Africa', 1863-1872

Andrew Bank

University of the Western Cape

Visual anthropologists have amply demonstrated the crucial role that photography came to play in the emergent discipline of anthropology in Europe and the United States during the nineteenth century. They have pointed to the coterminous emergence of anthropology as a field of study, in which the establishment of the Societe Ethnologique de Paris in 1839 and the Ethnological Society of London in 1843 may be seen as founding moments, and the invention of the daguerrotype and Fox Talbot's calotype in 1839. They have highlighted the relatively privileged methodological space that photography came to occupy in the discipline in subsequent decades, an era in which photographs were still celebrated as holding up a 'pencil to nature' (in Fox Talbot's phrase). Photography came to assume the kind of role in the methodology of mid-late nineteenth century anthropology that fieldwork would occupy in the era of Malinowski and his heirs.2

The ways in which anthropologists came to use photography in the service of their discipline were highly diverse. These were to include 'the recording of noncollectible native architecture and art in the field; the serial photographing of behaviour and ritual; the photographing of scenes and activities to serve as illustrations in expositions and museum exhibitions; the documenting of excavations and their artifacts; the illustration of professional publications, and the popularising of anthropology through visual images'.3 But during the period in which anthropology was still a very young discipline, photography served primarily as a means of documenting and cataloguing 'racial types',4 a project rendered all the more imperative by the 'salvage' logic governing the new discipline.5

'Racial type' photography was established as a genre during the 1860s and 1870s. There is evidence of methodological or empirical precedents. To cite some examples, the profile portrait, the building block of the new genre, had a distant 'ideological precursor' in the Physionotrace, a technique invented in 1786 for tracing profiles on glass with an engraving tool, which could generate images that were reproducible.6 The earliest extant photograph taken in southern Africa in 1845 was, rather ominously, a 'racial type' side profile daguerrotype of a 'Native Woman of Sofala',7 while America's leading racial scientist, Louis Agassiz, commissioned a series of daguerrotypes of African-born slaves to provide supporting data for his biologically-based theories of race during the 1850s.8But it is in the more systematic projects of the Societe d'Ethnographie in Paris to record 'human types' and the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences to photograph the 'races' of the Russian Empire, both launched during the 1860s,9 that we can see the marking out of a new visual field.

It was also from the 1860s, 1870s (and 1880s) that portrait photography came to be used in 'repressive' ways in other fields of knowledge. Sekula, for example, has demonstrated how the long-standing 'honorific' tradition of portraiture, derived from painting, became subverted as portrait photographs came to be used for the purposes of state classification and control in this period:

'Photographic portraiture began to perform a role no painted portrait could have performed in the same thorough and rigorous fashion. This role derived, not from any honorific portrait tradition, but from the imperatives of medical and anatomical illustration. Thus photography came to establish and delimit the terrain of the other, to define both the generalised look - the typology - and the contingent instance of deviance and social pathology.10

Sekula traces this shift to 'repressive' uses of the portrait photograph in the newly established fields of criminology and eugenics.

But, as Tagg demonstrates, the use of photography in new disciplinary fields needs to be tied to a very closely historicised understanding of 'evidence'. It is only within specific institutional contexts and the rules of logic governing individual disciplines that we can properly understand the ways in which these photographic spaces were constituted:

[W]hat Barthes calls 'evidential force' is a complex historical outcome and is exercised by photographs only within certain institutional practices and within particular historical relations ... In the nineteenth century, for example, we are dealing with the instrumental deployment of photography in privileged administrative practices and the professionalised discourse of new social sciences -anthropology, criminology, medical anatomy, psychiatry, public health, urban planning, sanitation and so on - all of them domains of expertise in which arguments and evidence were addressed to qualified peers and articulated only in certain limited institutional contexts, such as courts of law, parliamentary committees, professional journals, departments of local government, Royal Societies and academic circles.11

In this paper I will apply these theoretical arguments about the transition from 'honorific' to 'repressive' uses of portrait photography and the mobilisation of photographs as particular documentary, realist forms of evidence within specific disciplinary fields to a detailed reading of a particular case study: the portrait photographs of 'the natives of South Africa' 12 taken by a German anthropologist, Gustav Fritsch between 1863 and 1866, and then published in reconstituted form in an anthropological study of 1872. I will argue that during his travels in southern Africa, Fritsch conceived of his portrait photographs in an 'honorific' tradition. His original photographs in the field, which retain perhaps something of the 'cult' or 'fetish' status of the unreproducible daguerrotype,13 are best classified as 'ethnographic',14 given their predominant cultural emphasis. These original photographs will be read alongside his travel narrative and their open-ended ethnographic emphasis related to his early racial liberalism.

When the same photographs were re-presented (with technical modifications) in his anthropological study, they were invested with very different meaning that had shifted towards the 'repressive' pole of portrait photography. The emphasis of the selection of portraits that he published in hierarchically arranged form in his scientific study was firmly on the physical, the differing and defining features of 'racial types' in southern Africa. The reasons for this change from ethnographic-cultural to anthropological-physical meaning in his portraits will be related primarily to his integration within a newly institutionalised German and more particularly Berlin anthropological community and his gropings towards a new methodology within this intellectual context.

The 'Ethnographic' Portraits of 1863-6: Background Context

Before analysing Fritsch's photographic portraits, it is necessary consider, firstly, the state of German anthropology at the time of his travels and, secondly, the unusual position he occupies in the embryonic field of expeditionary photography in southern Africa. Fritsch's travels predated the internal institutionalisation of German anthropology. By contrast with the British and French traditions, where anthropological societies and journals were already up and running by the 1840s and 1850s, it was only during the late 1860s that anthropology in Germany began to become institutionalised beginning with the founding of the Berlin Society of Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory ('Berliner Gesellschaft fur Anthropologie, Ethnologie und Urgeschichte') in 1869 and the establishment of the journals Archiv fur Anthropologie in 1866 and Zeitschrift fur Ethnologie in 1869.

In the early 1860s German 'anthropology', if we can speak of it as a discipline, had barely emerged and only on the fringes of a range of allied disciplines. The eclecticism and haziness of its boundaries in these years is perhaps best captured by Massin who claims that German physical anthropology (and German anthropology was strongly physical from the outset) 'was formed at the crossroad of a number of scientific traditions: medical and comparative anatomy, craniology and anthropometry; geography, ethnology and linguistics; archaeology and history; and geology and palaeontology'.15 Even if medicine became the cement of the new discipline, as Proctor recommends, the line between 'anthropology' and the cultural sciences, which had already taken clearer disciplinary shape (in the sense of an established methodology and institutional base) was still a fine and porous one.16

Fritsch's own background fits quite neatly into this characterisation of the prehistory of German anthropology. Like Rudolf Virchow, Adolf Bastian and Johannes Ranke, 17 the dominant figures in the new discipline, he came to anthropology from a medical background, having studied natural sciences and medicine at Berlin, Heidelberg and Breslau Universities between 1857 and 1863. Yet his interests were still highly eclectic during the late 1860s, covering a range of cultural and natural subjects, as his earliest publications based on the data that he collected in southern Africa suggest. He published an article on 'The Insects of South Africa' in the Berlin Entomological Journal in 1867, an article on 'The Diseases of South Africa' in the Berlin Archive for Anatomy and Physiology the following year and one on 'The Climactic Conditions in South Africa' in the Berlin Journal of Geography in 1869.18

To turn briefly to the southern African context, Fritsch's expeditionary photography while not entirely unprecedented was very unusual. The beginnings of expeditionary photography in the region have been traced to Charles Livingstone and John Kirk's 1858 Zambezi Expedition. Earlier traveller-scientists, like the later inventor of eugenics Francis Galton who travelled through present-day Namibia in 1851 or explorers into present-day Angola from Luanda and Benguela, produced ethnographies and museum specimens, but no photographs.19

The closest comparable contemporary portfolio is perhaps that compiled by James Chapman on his expedition to the Victoria Falls in 1862.20 But besides the technical difficulties they shared in this very early era of expeditionary photography, the comparison with Chapman only really serves to highlight the distinctiveness of Fritsch's photographic project. While Chapman's motives were as much commercial as scientific (reflecting his goal of obtaining commercially profitable views of Victoria Falls, in the end unsuccessfully), Fritsch seems to have conceived of his photographic mission in as strictly and systematically in the service of science. Where Chapman's portfolio of stereographs was diffuse in its subject matter (including shots of hunting conquests, group ethnographic photographs, individuals, buildings, landscapes, plants) that of Fritsch was highly focussed and genre-specific. Even the consistently fine quality of the Fritsch portraits, partly because of their much more rigorous scientific intent, contrasts with the mixed and uneven quality of the Chapman's stereographs.

The 'Ethnographic' Portraits of 1863-66

Fritsch indicated right at the outset of his expedition that his aims were 'ethnographic' and 'anthropological' (he used the terms loosely and almost interchangeably in his 1868 travel narrative) and the collection of a portrait portfolio of 'natives' ('eingeborenen') was the most important aspect of this project.21 During the following three years he travelled through the western and eastern districts of the Cape Colony, Natal, the Orange Free State and Bechuanaland, and photographed more one hundred individual 'native' subjects, all in both front and side profile portrait form. The South African Library in Cape Town has 48 of these original portraits, donated by Fritsch to the Grey Collection (presumably when he left the Cape in 1866) and the Berlin Museum of Ethnology has 128 of the original portraits, loaned permanently by the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory in the 1950s.22

Although Fritsch made no textual reference to the exact photographic technology that he was using, it possible to reconstruct some of the details as to how he took these 'native' portraits and the nature of these photographic occasions from the photographs and a close reading of his travel narrative. The period of his travels considerably predates the invention of the handheld camera and, like his contemporaries, Fritsch was forced to work with a cumbersome tripod camera and carry his plates and chemicals with him in the field for on site development. A woodcut image in the travel narrative shows the bulky photographic apparatus (described in the caption as 'the photographic tent') with Fritsch, his ox-waggon and Bechuana waggon-driver alongside.23

As was presumably the case with other portrait photographers at the time, he photographed his subjects in a seated position. He complained frequently in his travel narrative of the restlessness of African subjects during these sittings, whether Xhosa chiefs or elderly 'Bushmen'. In two of the portrait photographs, one of which was recycled in completely decontextualised form in a much later popular account of the 'pacification' of German South-West Africa,24 the chair is still visible in the photographic original. It is possible that Fritsch, like some of his anthropological contemporaries, was tempted to delete evidence of his makeshift 'studio' background from other original portraits while developing the photographs from silver plates in the field. Edwards notes that such deletions were not uncommon at the time. In a German anthropological photographic project launched in 1870:

There are a number of pictures which have been taken in the field rather than in the studio. In order to render them anthropological in both photographic and iconographical terms, the background or the context has been painted out of the negative, thus stressing the decontextualised nature of the subject. In some cases this was done before the photographs were copied for the project but some of the surviving wet collodion plates for the copy negatives from the project, in the Pitt Rivers Museum Archive, show that the overpainting on the negative was done specifically to produce these images in a form for anthropological consumption.25

The most striking feature of the collection of Fritsch's portraits in the South African Library's collection is their great diversity. In keeping with the 'honorific' tradition of portraiture, Fritsch photographed many African chiefs, their counsellors and relatives. His attempts to capture African nobility on camera began while he was still in Cape Town. He embarked on an expedition to Robben Island in November 1863, armed with 'photographic apparatus and guns'. Having met the Xhosa chiefs on the island, who had been in exile there since 1858 for their involvement in the Xhosa Cattle Killing, Fritsch stayed overnight and photographed them the following day, with offerings of 'tobacco and 1 shilling per head' by way of inducement.26

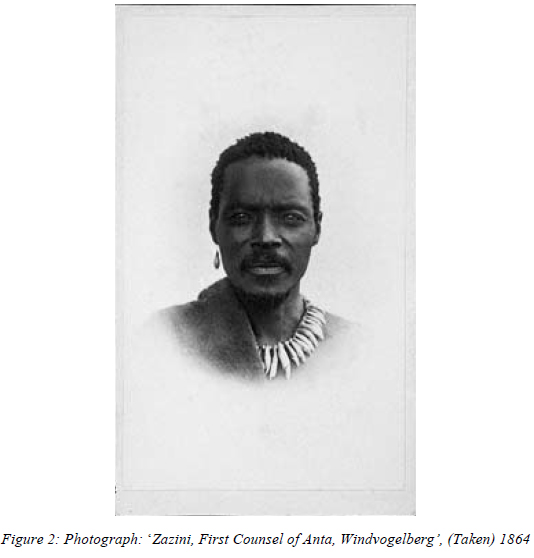

His portraits of the Xhosa chiefs are perhaps his best known photographs. His image of Maqoma appears on the cover and in the text of a recent edited collection on the history of Robben Island.27 A poor quality side profile view of Stokwe is reproduced in the body of the book and it was perhaps this photograph that Fritsch had in mind when he commented that 'some of the portraits left much to be desired'.28 Xoxo, Seyolo and Dilima were also photographed on this Robben Island trip, while two Xhosa chiefs and their first counsellors were photographed in hotels in small towns in the Eastern Cape: Hanta (Anta) and Sazini in Windvogelberg (modern Cathcart), and Sandile and Somi in Stutterheim.

On his later journey through Bechuanaland, Fritsch also photographed numerous Bechuana chiefs and their families: the chief of the 'Bakuena', Secheli and his son Sibelo; Kama, the son of the chief of the 'Bamangwato'; Motuane, 'the favourite wife' of the chief of the 'Bawanketsi' and his brother-in-law (unnamed). On other occasions he photographed a Korana chief, Zwart Faan and his father, Gerrit, and Umpotla, the son of the Matabele chief, Mzilikatsi.

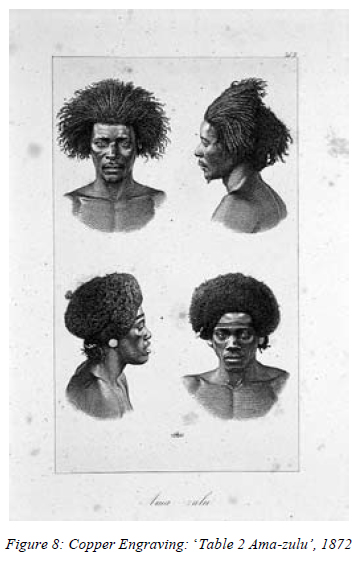

Perhaps the most striking omission in his collection of photographs of African notables is the absence of any portraits of Zulu chiefs or counsellors. Whether this was due to difficulties of access or perhaps a reluctance on Fritsch's part to venture into the strongholds of the nobility of the still unconquered Zulu is not stated in the travel narrative. Instead his portraits of the Zulu attempt to document on a distinctive cultural practice: that of hairstyling.29 The Zulu portraits are among the most aestheticised of his photographs and he seemingly chose to depict this cultural practice in order to highlight the relatively civilised status of those he saw as the most 'noble' of southern African peoples. According to the description in his travel narrative, Drei Jahre in Sud-Afrika: Reisekizzen nach Notizen des Tagesbuchs Zusammengestellt, that was published in Germany in 1868 but based (as its subtitle indicated) on diarised notes he made at the time in the field: 'One is soon aware that one finds oneself here amongst a thriving group of natives when one sees the muscular bodies and the beautiful men of stately build. The powerful development of the body is the rule amongst the Zulu ... This favourable impression is heightened by the distinctive hair-dress of most of the armed men'.30

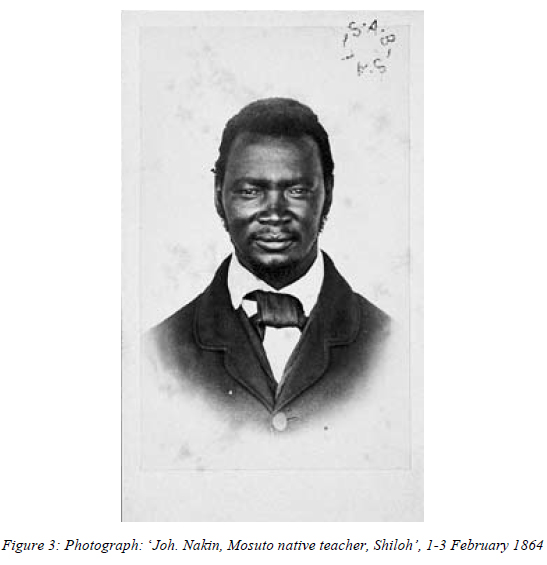

Perhaps the second most prominent group of individuals that sat before Fritsch's camera were the inhabitants of mission stations. He took photographs of African converts at the Moravian mission station of Shiloh (near modern Queenstown), at the Berlin Missionary Society's station at Bethanie (near Bloemfontein) and at the London Missionary Society's station at Kuruman. His portraits of Africans on these mission stations typically depict the impact of westernisation, and particularly Western dress, on indigenous cultures. A series of portraits that he took at Shiloh, for example, portray three adult 'Hottentot' converts - Karl Stompjes, A.Minell and R.Schlinger - in jacket, shawl and dress. On the reverse side of the original photograph Fritsch recorded the names and ethnic identities of his photographic subjects. This was one of the rare instances where the Africans he photographed had surnames, presumably given to them subsequent to their conversion.31

His photographic portrait of the 'Mosuto native teacher' at Shiloh, Joh. (John or Johannes?) Nakin, presents a more complete example of cultural change on the missions. In this frontal portrait Nakin appears in the accoutrements of the European gentleman: his waistcoat peeking out beneath the neatly buttoned up jacket and his carefully tied dark cravat thrown in relief against his white shirt. The contrast of light and dark clothing are mirrored in Nakin's visage with a dark outline framing and highlighting the teacher's fine facial features. Fritsch would later circulate this image amongst his anthropological colleagues at a meeting of the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory (henceforth 'Berlin Society') to demonstrate the impact of Western civilisation in southern Africa: 'I will pass around a picture of the Chief Moshesh whose clothing indicates the influence of civilisation on him; so too in the case of this photograph of a Basotho, who grew up on the mission station at Shiloh and excelled in intellect.'32

There was a very practical reason for this partiality for mission subjects. Like Chapman, Fritsch made frequent reference to the great fear with which Africans viewed his imposing photographic technology.33 In order to win the trust of prospective and potentially fearful or reluctant subjects, Fritsch had to enlist the support of intermediaries.34 The missionaries were obvious candidates given their close contact with Africans and knowledge of African culture and language. In his travelogue Fritsch expressed gratitude to Robert Moffat for his hospitality and assistance with 'my photographic labours'.35 It was with Moffat's permission and help that Fritsch photographed 'Malimbe, a Marolong' living at Kuruman. Moffat himself also sat before Fritsch's lens and his portrait is the only example of a European portrait in the Fritsch collection.36

Fritsch's rapport with the Berlin missionaries at Bethanie, Wuras and Meiffert, presumably accounts for his success in capturing four portraits of mission subjects there. He records his gratitude at being 'given a very friendly reception at Mr. Meiffert's house and ... assisted in every respect by the missionaries in my [photographic] work'.37 But not all of the missionaries were equally accommodating.38 He relates an incident where the reluctance of a missionary to assist him in convincing Africans to sit before his lens prompted him to induce compliance by less subtle means: 'I hoped to obtain some material for my anthropological studies from a sizeable Fingo settlement near Port Elizabeth. I took my apparatus out and approached the appointed missionary (spiritual advisor), but he would do nothing for me. Some of the natives showed great fear of the bulky apparatus, others were bold enough to sit before the camera for 20 seconds in exchange for 5 shillings'.39

The importance of intermediaries in his photographic project is a theme that resurfaces a number of times in the travel narrative, but one which, significantly enough, he chose to efface in adopting the more authoritative voice of the scientist in his anthropological study of 1872. He wrote of his use of 'an assistant' while experimenting photographically in Cape Town before he set out on his travels, noting that this was 'the first time' (suggesting there were others) that 'I used the services of a coloured ['Farbiger'] helper'.40 On a later occasion he complained later of his failure to find a facilitator to assist him in the setting up or taking of portraits of the Zulu: 'Among the large number of Zulus wandering the streets of Petermaritzburg, I saw many beautiful specimens that I wanted to add to my 'gallery', but in the absence of an intermediary ('einer Mittelsperson') I was unable to capture them'.41 Whether he required this 'Mittelsperson' for the initial purposes of persuasion or for translation in guiding the potential photographic subject through the rituals of the photographic occasion (or both) is left unstated.

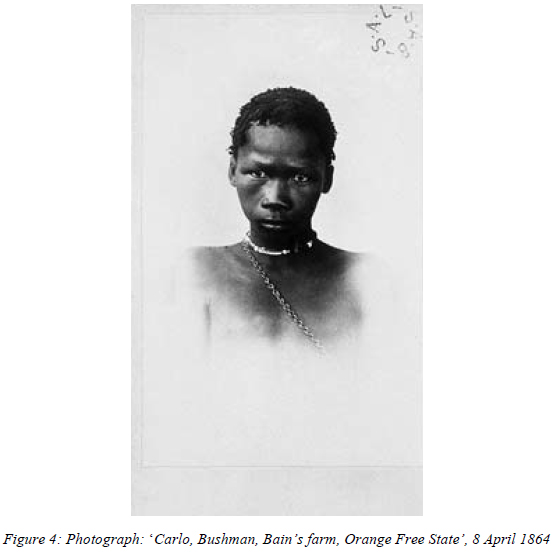

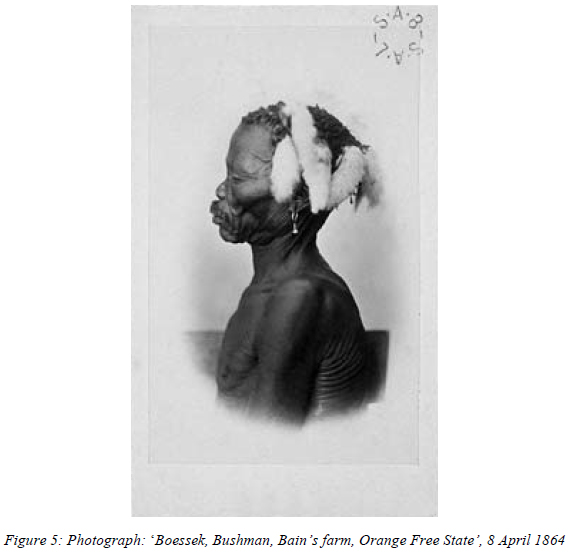

The remaining portrait photographs in the collection are an eclectic mix, but again it seems that intermediaries (and therefore location) played a crucial role in facilitating his photographic work. Fritsch was invited by an English farmer, Bain, living near Bloemfontein in the Orange Free State, 'to gaze upon his rarities ... Bushmen of the purest origin that can be found in the land'.42 A woodcut image in his travel narrative, probably based on a sketch done by Fritsch on the farm, indicates that Bain had eight 'Bushmen' living on his farm. Fritsch photographed three of them on the 8th April 1864 and the South African Library collection has a single portrait of each - two in profile and one frontal (the corresponding pairing portraits are presumably in the collection in the Berlin Museum of Ethnography.

In all three cases the focus of the viewer's attention is drawn to ethnographic artifacts.43 The 'Bush woman', Sanna, is shown with a cloth blanket around her shoulders, a necklace and striking strings of white beads in her hair. Her son, Carlo, about whom Fritsch later recounted a heroic story of his success in keeping a hyena at bay with his bare hands44 (presumably told to him by the farmer), was photographed with a traditional bead necklace and metal chain slung across his chest, symbolic perhaps of the blend of cultural influences on the farm. The side profile view of the old man Boessek is the most ornate of the three portraits. Like many of the other portrait originals, it is of a remarkably fine quality and the details of the wrinkles on his torso and neck, as well as the veins on his forehead are very clearly visible. But the viewer's attention is drawn, above all (in a literal sense as well), to his highly exotic headgear : a swathe of white feathers almost entirely covering the head. In its aestheticisation of 'Bushmen' head-dress, although obviously not in its underlying scientific motivations, the image is reminiscent of the way in which the artist Samuel Daniell had earlier chosen to exoticise one of the 'Bushmen' figures foregrounded in his painting 'Bushmen Hottentots Armed for an Expedition'.45

Another identifiable and locationally specific group of portraits in the South African Library's collections are those that were taken in Durban of 'coolies from Madras' in early October 1864. Fritsch made no specific reference to the photographic occasion or any assistants that he may have enlisted, but wrote generally in his travel narrative of the superiority of Indian over African labour and of the colourful impression these Indian immigrants and their turbans made in the streets of Durban.46 These portraits are extremely unusual in that they are perhaps the only surviving photographic record of the first wave of immigrant indentured labourers brought into Natal. Between 1860 and 1866 over six thousand Indians were shipped to Natal and ended up working variously on sugar plantations, in the households of settlers or in government departments.47 Almost all of these early immigrants were from Madras or Calcutta and 85% of them were Hindus.48 Unfortunately, in the case of the three individuals photographed by Fritsch all we know are their names ('Wenkatazani' and 'Coota', though the third person is unnamed) and their origin.

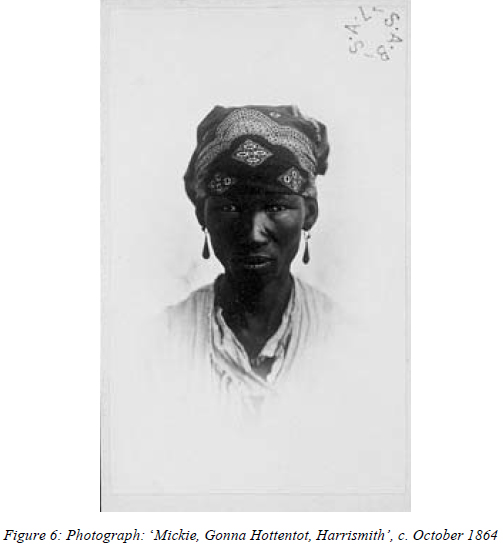

A final and more scattered 'group' of the portrait originals that warrants mention are the photographs that Fritsch took of young African women. Perhaps partly because they were head-and-shoulder portraits rather than full body photographs, there is little of the coyness or erotic investment in these photographs that is evident say in Chapman's stereograph of a 'Namaqua Belle' in seductive pose.49 His front profile view of 'Mickie, a Gonaqua Hottentot' is, as Schoeman suggests, one of his finest portraits with its delicate compositional balance of light and dark shade on the woman's face, and her dramatically silhouetted dark eardrops.50

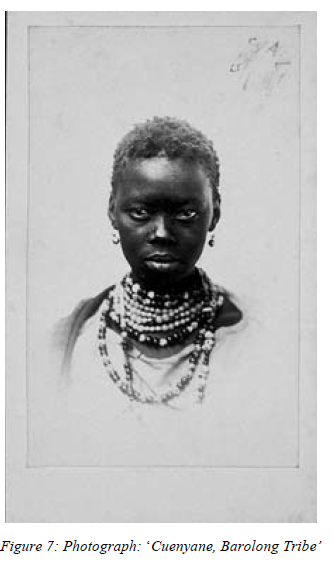

His photograph of 'Cuenyane of the Barolong tribe' emphasises her traditional culture as the viewer's attention is drawn particularly to her long bead necklace and its alterations of colour and bead size. The young woman looks out at the camera with an intense gaze (perhaps accentuated by the use of the flash). He later wrote that 'The portrait of Motuane, the favourite wife of the Bawanketsi chief Gassisioe, shows the most important female figure that the author encountered during his lengthy expedition among the Bechuana, that of Cuenyane perhaps the prettiest and yet nobody would mistake her for another Venus'.51 The barbed edge to this compliment must, however, be read partly in the light of its location in his 1872 study, and the marked difference in tone between the travel narrative of 1868 and the later scientific study.

Taken collectively then, the most striking characteristic of Fritsch's portfolio of original photographic portraits, apart from their fine quality, is their diversity and individuality. In keeping with the older 'honorific' tradition of portraiture derived from painting the images compel attention to the particular, the specific. This sense of specificity, whether the subjects of his portraiture were nobles or not, derives primarily from the remarkably varied range of cultural adornments worn by his African subjects - whether leopard tooth necklaces, felt hats, military uniforms, feathers, chains, waistcoats and cravats, earrings, beads, horns, blankets and karosses, hairpins stuck through elaborate styled heads of hair or handkerchiefs worn on the head.

Two Suggested Framings for the 'Ethnographic' Portraits

In analysing how we might conceptualise this portrait portfolio, I would suggest two possible framings. Firstly, some years after Fritsch donated this selection of his portraits to the South African Library, they were placed in a red leather-bound album, the Grey Ethnological Album, probably by Wilhelm Bleek who curated the Grey Collection until his death in 1875. This album came to include other photographs of the indigenous peoples of southern Africa, both groups and individuals, taken between Fritsch's departure in 1866 and about 1880. The relatively unsystematic ordering of the Fritsch portraits within this album, while obviously partly the product of Bleek's own notions of classification, arguably also reflected the spirit of specificity and eclecticism of the photographs themselves.

The Grey Ethnological Album was loosely ordered along ethnic lines with photographs of 'Bushmen', 'Hottentots', Bechuana or Zulus usually presented together. But elsewhere the photographs were arranged by photographer or donor. The four photographs taken by Theophilus Hahn of different ethnic groups in today's Namibia were grouped together, as were the group photographs of 'Bushmen' prisoners at the Breakwater Prison donated by Wilhelm Bleek and the field-work-type ethnographic photographs of Zulus in Natal taken (or donated) by Captain Walmesley.52

Fritsch's portraits were scattered amongst the photographs bequeathed by these other donors. While they were sometimes grouped thematically - the Xhosa chiefs, the three 'Bushmen' on Bain's farm, the Madras 'coolies' each appeared together on the same pages - the ordering was typically ad hoc. On the opening page of the album, for example, front and side profile views of a 'Gonna Hottentot' Mickie (one of the very few instances of two views of the same individual in this collection) featured above front and side profile portrait photographs of a 'Bushman in the Kalahari Desert' donated by Bleek. A few pages later, Fritsch's portraits of the Korana chief Zwart Jaan and his father Gerrit, and portraits of two Griqua men, Nero and Piet Nero, were slotted in alongside Bleek's photographs of two 'Bushmen', Klaas Stoffel and the chief informant he relied on for his 'Bushman research' of the early 1870s, Jantje Tooren or //Kabbo.53

Fritsch's portraits of Zulu men with elaborately styled hair appeared above a photograph of a 'well dressed Fingu' presented by Jane Waterson. His photographs of 'Umpotla, Matabele' and Robert Moffat (perhaps not surprisingly in the latter case given that it is the only portrait of a European in the Album) simply featured on their own on separate pages. This unsystematic ordering of the portraits, whether intentionally or not, was in keeping with the spirit of the initial photographs and stands (as we shall see later) in marked contrast to the way in which the portraits came to be reframed in Fritsch's anthropological study of 1872.

The second way of thinking about the original portraits as a collection is by reading them in the context of the field notes that Fritsch made at the time and published in narrative form in Germany in 1868 in what was explicitly conceived as a popular travel account. Drei Jahre in Sud-Afrika helps to address the question: why did Fritsch choose to aestheticise the 'natives of South Africa' by drawing attention to cultural diversity rather than physical difference or deviance?

To begin with, there is no evidence of the type of commercial motives that led other ethnographic photographers to aestheticise 'racial types' at the time.54 The first evidence that I have thusfar encountered of any commercial aspect to Fritsch's photography only surfaces much later. In 1876, at the instigation of the Berlin Society, he sold prints of a photograph that he had taken of a woman from Papua New Guinea, Kandaze. She had been brought to Berlin as a domestic servant by a missionary and was one of many non-Europeans who were paraded before the Berlin anthropologists at their meetings. Fritsch's photograph was described rather contradictorily as showing her 'clothed but naked down to the hips' and was offered to titillated colleagues at the price of 1 Mark.55

The narrative suggests instead that the empathetic quality and cultural emphasis of Fritsch's original portraits be read in the light of his racially liberal attitudes. Rather surprisingly in view of his medical training, Fritsch's ethnography in Drei Jahre is dominated by 'sentiment' rather than 'science' (to adopt the broad conceptual distinction that Pratt applies to travel narratives of an earlier period).56 He casts his first person narrative in the mould of the romantic adventurer and draws quite liberally on the by now tired genre of the Noble Savage. His idealised description of the Zulu has been cited above. Earlier he had written of 'the long, narrow figures of the Xhosa' associating their dress with the 'Roman toga' and their ochre-reddened faces with those most romanticised of 'savages', the 'natives of the American wilds'. Even in the case of the 'Bushmen', perhaps the most consistently disparaged of non-European peoples, Fritsch suggested that 'the freedom and independence of their lifestyle gives their whole being a distinctly noble stamp'.57

He reported elsewhere on the acuity of his Bechuana waggon-driver whom he overheard discoursing about the relationship between 'Bushmen' and apes in a way that closely resembled the thinking of Darwin. It led him to muse 'how good it would be to present such a man to the Philanthropic Society in England as a representative of the natives [of South Africa]'.58 Like Livingstone and the more liberal missionaries, he was also unsparing in his criticisms of the racism of the 'Boers' of the interior, disparaging at different points their refusal to shake the hands of Africans, their classification of the 'Hottentots' as 'schepsels' (creatures outside of the human realm) and their 'merciless' efforts to exterminate the 'Bushmen'.59

The picture of African ethnic identities in these field notes-cum-travel narrative is fluid and appears to contradict any strict biological notions of 'racial type'. Although he wrote at a number of points of his quest to record 'pure racial types' through his photography, the narrative reveals that this ambition was constantly being frustrated by evidence of hybridity on the ground. In one area where 'the mixed race is mostly of the Hottentot type with ... pointy face, flat nose and yellow-brown colour', he complained that 'it was difficult to identify the pure race and get photographs of them'. At his 'first opportunity to get pictures of the coloureds who call themselves "Griqua"', he reported that 'I could not really describe the individuals as particularly characteristic of this tribe.

While the hair remained short and curly, there was an undeniable mixing of white blood'. Even in the case of those he viewed as the most noble of African peoples, the Zulu, he was forced to concede that their 'external appearance is so diverse that it is difficult to fix an exact type ... [T]here is great diversity in skin colour; [and] while [it is] usually deep dark-brown, some have lighter, more reddy-brown tones although the overall physical make-up rules out any possibility of mixing with white blood'.60

Fritsch's attitude towards photography itself was also interestingly both more cautious and experimental while he was still in the field. He commented frequently on his trials with various techniques, especially during the early stages of his travels and was not averse to admitting to the limitations of his craft, complaining at one point of his frustrations at not being able to capture a sense of movement and cultural interaction within a static medium.61 This stands in contrast to the much more self-confident posture that he was later to assume regarding the scientific value of photography. His comments on the importance of photography for the new discipline of anthropology during the 1870s and 1880s were characterised by a growing degree of assertiveness.62 But this is a later chapter in Fritsch's life and work, and we need now to return to how he came to re-present a selection of his portraits within a very specific institutional and intellectual context.

The 'Anthropological' Portraits of 1872: Background Context

Within days of returning from southern Africa, Fritsch enrolled in the Prussian Army and was later to fight in the Franco-Prussian War. But these military interludes apart, the period between 1866 and 1872 was one in which he embarked on an academic career. In 1867 he was appointed as an assistant at the Institute of Anatomy at Berlin University. The following year he both had Drei Jahre published and accompanied an archaeological expedition to Egypt as official photographer. Four years later he secured a permanent appointment as a lecturer in the Anatomy Department at Berlin University, partly on the basis of his skills as a photographer.63 This was also the year in which he was elected onto the Committee of the Berlin Society serving as Assistant Secretary for the following three years.64

These were the very years in which German anthropology became established as an academic discipline. The hazy and unformed 'anthropology' of the early 1860s was transformed by the early 1870s into a relatively clearly defined and firmly institutionally based field of study. As noted earlier the founding of the Berlin Society and its journal Zeitschrift fur Ethnologie in 1869 were decisive moments in the process of internal institutionalisation.65 Dominated by the forceful and politically influential Rudolf Virchow,66 the new discipline burgeoned in the following decades both in terms of its following and the sophistication and quantity of its academic output. It had 120 members in 1872, but by the turn of the century could boast a membership of over five hundred (of whom 300 were based in Berlin) and twenty-five regional anthropological societies.67There is a perhaps a kernel of truth in Gordon's exaggerated claim that anthropology in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was 'largely a Germanic phenomenon'.68

Historians of anthropology have also emphasised the strong physical orientation of the new discipline in Germany (and France), contrasting it with the more philosophical and evolutionary-oriented anthropological traditions of Britain and North America. According to Stocking,

in France and Germany ... it [physical anthropology] was spoken of by the unmodified term 'anthropology' and often opposed to 'ethnology' which referred to a more culturally oriented study of human diversity that was tied to the earlier monogenetic tradition. In Anglo-American anthropology, where the influence of the old ethnological and new evolutionary tradition was somewhat stronger, physical anthropology (sometimes designated 'somatology') became simply one of 'four fields' of a general 'anthropology', which included also ethnology (later social or cultural anthropology), linguistics and prehistorical archaeology.69

But, as Zimmerman demonstrates, Berlin anthropology came to occupy a very distinctive space within this physically oriented German tradition and in ways that have direct relevance to Fritsch's portrait photography. Firstly, the Berlin anthropologists privileged visual over textual modes of representation. Photography (and allied technologies of visual representation like the Lucaesian apparatus)70 came to occupy a central methodological place among a community of scholars who partly defined their discipline in opposition to the humanities and its traditional textual and linguistic orientation. Secondly, the Berlin anthropologists were concerned, above all, with the study of non-Europeans. This was in marked contrast to Johannes Ranke and many other colleagues outside of Berlin, who saw the study of 'Self' through Germany prehistory as the most urgent anthropological priority. Thirdly, the Berlin anthropologists, partly because of their natural scientific training, adopted a firmly empirical methodology, which led them to view grand theory (whether Darwin's theory of evolution or the British anthropologists' preoccupations with models of progress-in-civilisation)71 with skepticism if not outright hostility. Fourthly, the Berlin anthropologists, notably Virchow and Bastian, played a leading role in shaping a racially liberal ideological orientation in the new discipline.72 But the position of Fritsch with regard to the latter two points was, as we shall now see, both ambiguous and atypical.

Re-presenting the Portrait Photographs in Die Eingeborenen Sud-Afrikas, 1872

In 1872 Fritsch had published a selection of his original portraits (in modified form) in the second volume of his first major anthropological study, Die Eingeborenen Sud-Afrikas: Ethnographisch und Anatomisch Beschreiben ('The Natives of South Africa: Ethnographically and Anatomically Described'). The first volume provided a detailed physical anthropological and ethnographic analysis of the indigenous peoples of southern Africa in textual form with a series of lithographic plates appended comparing the skulls, skeletal features and skin colours of the different 'races'. As a number of scholars have noted, this was the first systematic scientific study of the physical anthropology of the indigenous peoples in southern Africa.73 It provides part of the framework within which to locate his re-presentation of portrait photographs of sixty of the 'natives of South Africa' in a separately bound volume.

The technical problems posed by the reproduction of the original photographs at a time that just predated the invention of the phototype or half-tone process in Germany, which would have allowed for the direct use of the photographs as illustrations,74 prompted Fritsch to have the original photographs converted into copper engravings. While he confidently promoted the anthropological value of photography to his colleagues at meetings of the Berlin Society from the early 1870s onwards, he was rather anxious and defensive about the scientific integrity of this process of conversion:

Mr. Fritsch placed a portrait collection of South African racial types before the Society that belongs to a larger work on the natives of South Africa and explained the principles that guided the presentation of this collection of portraits with special retrospective [my emphasis] attention to their physiological characteristics ... [He said that] 'The further use of photographic portraits required careful consideration. It was unfortunately not advisable to use the photographic originals themselves as illustrations and on the following grounds: It was not possible with the changeable external circumstances and difficulties of [photographing] on the expedition, to obtain negatives of sufficient quality from which proper and consistent copies could be made. Further the original prints ('silberdrucke'), even in cases when the plates have been well washed, deteriorate rapidly when reprinted in books and become yellowed; a single, poorly reproduced photograph ... can distort the integrity ('Zusammenhang') of an entire collection'.75

Fritsch was evidently motivated by a desire to reproduce the originals in a scientifically accurate and consistent, but also aesthetically pleasing form. But the change from the originals to the published photographs involved very much more than a technical alteration. The way in which Fritsch came to select and order these copper engraved versions of his portraits lent themselves to a physical anthropological (and perhaps Darwinian) interpretation that diverged markedly from the spirit and emphasis of the original photographs and photographic occasions.

He streamlined the collection in such a way that the evidence of racial mixing or fluidity of identity that can be read from his travel narrative and original photographs was excised. The exclusion of say the figure of Moffat or the three Indian 'coolies' in Natal is hardly surprising in a portrait collection of 'the natives of South Africa'. But his choice to leave out portraits of the Griqua (whom he discusses at some length in the text of volume one), 'Bastards' and all other 'coloureds' ('Farbigen'), including the 'Malays' in Cape Town that were his first photographic subjects, suggests that he was concerned not to muddy the picture of racial purity that his collection was trying to present.

He also selected the portraits in a way that accentuated the 'traditional' and downplayed evidence of cultural hybridity. Mission subjects and Africans in Western dress feature far more prominently in the wider collection of photographic originals that in the streamlined collection of portraits published in his scientific study. He would have been aware that images of the likes of John Nakin would create a more complex impression of group identity and threaten to unsettle the idea of 'racial purity' implicit in the notion of 'racial types'. Moreover, he favoured the choice of portraits where the head and chest were exposed, given their superior scientific value. Again his reference to 'retrospective' considerations in his introductory comments to volume two point to the discrepancy between the spirit of the original and those of the republished portraits. 'With retrospective consideration to the clear presentation of anatomical features, the head and chest of the individuals should probably have been exposed', but in mitigation he explained that his photographic subjects, particularly African chiefs and Africans on mission stations, were resistant to being photographed without Western cultural adornments.76

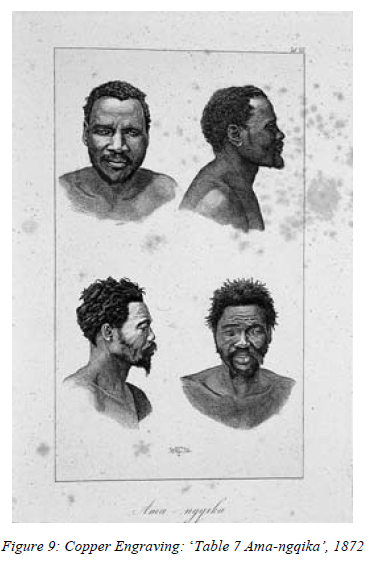

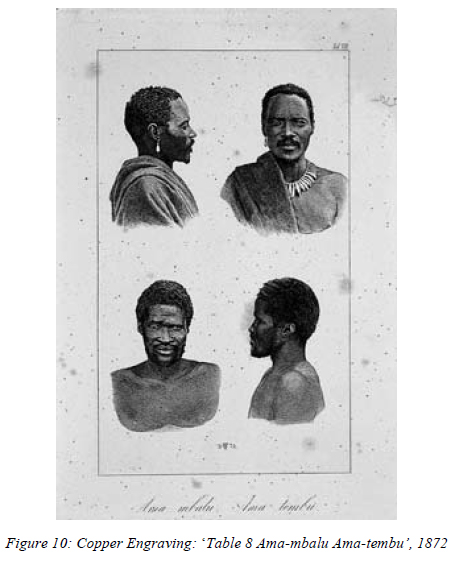

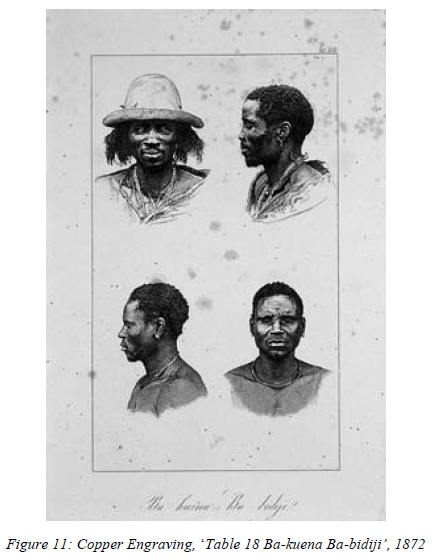

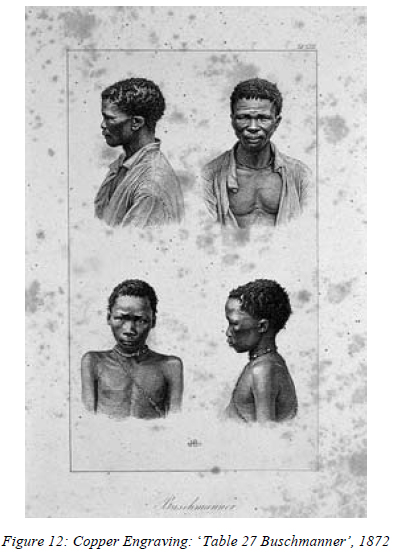

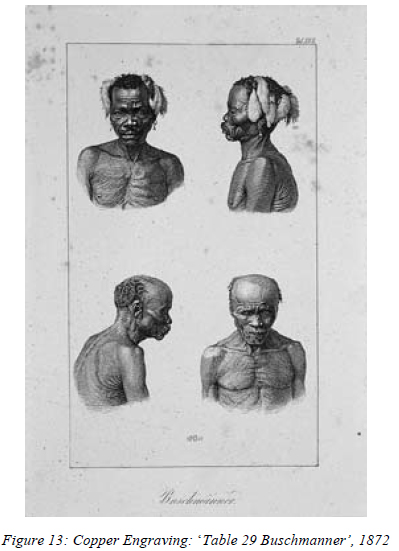

The way in which the portraits were arranged in the separate 'Atlas' of 'racial types' is also revealing. Like the lithographs of skulls, skeletal features and skin colour in the plates appended to volume one, the portraits of volume two were presented in hierarchical order. Rather than following the geographical distribution of the peoples of southern Africa as he encountered them on his travels, 77 he graded his portraits in descending racial rank. They went from the 'A-Bantu' down to the 'Khoikhoin', but were also subdivided by rank within these categories: the 'A-Bantu' going from the Zulu, the Matabele and then the Xhosa down to Sotho-Tswana peoples (more diversely labelled) and the 'Khoikhoin' from the 'Hottentots' through the 'Korana' down to the lowly 'Bushmen'.78

This ordering was probably motivated by cautiously Darwinist ideas, although the connection cannot be assumed. Contrary to Zimmerman's claims that Fritsch was anti-Darwin in the early 1870s,79 his study and responses to critiques of his work at the time suggest otherwise. It is true, as Zimmerman notes, that his study was not centrally concerned with the question 'ob Affe, ob nicht' ('ape or not ape') - after all, Darwin's Descent of Man had only been published the previous year - and that he was outspokenly critical of the 'crass' way in which some of Darwin's young disciplines, notably Haeckel, came to use evidence in support of an evolutionary, biologically-based anthropology. But he also very clearly stated in the introduction to his study that 'Darwin's theories belong to the future, and even today there are few who are not convinced of the importance of the Englishman's newly developed research'. In responding to a Darwinian's critique of his work, he insisted that 'the impartial reader of my book would gladly concede that my criticisms are not directed at the foundations of the Darwinian theory of evolution but rather at the misuse thereof'.80

The very way in which the portrait photographs were re-presented then encouraged a very different reading from that of the original photographs. The translation into copper engravings, however anxiously Fritsch justified its scientific integrity, lent a grey and lifeless character to the animated and high quality original prints. The portraits from the wider collection were selected in such a way that signs of racial mixing were written out and those of cultural hybridity downplayed, and the 'racial types' in the album were strictly hierarchically arranged, probably a product of Fritsch's commitment (albeit still somewhat cautious) to Darwin's theory of evolution.

The 'Anthropological' Portraits of 1872

Where the emphasis of the original portraits in the field had been on individuality and cultural diversity, that of the published portraits was on physical and racial differentiation. Where the cultural artifacts had been the focus of the initial prints, it was now the bodies and heads of the 'natives of South Africa' that were put up for scrutiny by specialists within a newly defined disciplinary space. In short, it is within the context of the growing preoccupation with craniometry, allied to the rise of physical anthropology,81 that the re-presented Fritsch photographs were meant to be read.

The series begins, as noted above, with the Zulu. But the focus on their elaborate hair-styling rituals, while of earlier ethnographic interest, is of diminished value for the anthropologist eager to interpret information from the configuration of the head. Anthropometric photographers at the time preferred to present their subjects with bald or shaved heads, which was usually only possible in cases where these subjects had no rights of refusal (for example, prisoners or criminals). The difficulties of deriving craniometric information from the portraits themselves, however, are compensated for by the inclusion of an introductory classificatory table. Apart from the name, tribe ('Stamm') and approximate age of all the photographic subjects, this table records height and two measurements that Fritsch made on each of his living subjects by means of callipers: a measurement of the width of the face across the jaw and of head height taken from the chin to the top of the head. The application of callipers could be very uncomfortable as accurate measurement necessitated a very tight pinching of flesh,82 and it was probably for this reason rather than superstition ('Aberglauben') that Fritsch was unable to obtain readings from some of the subjects, notably the Xhosa chiefs.

While measurements on living subjects were obviously taken while Fritsch was still in the field (and therefore point to the importance of the scientific motivations of the medically-trained traveller despite his later casting of the narrative in Drei Jahre in 'sentimental' idiom), their relationship to the portraits is only really set up in the published anthropological study itself. Fritsch was somewhat apologetic about the limited number of measurements that he had taken on living bodies in the field and perhaps partially by way of compensation to his specialist scientific audience made hugely detailed measurements of the skulls that were presented in his lithographic tables and that he had access to in the collection of the Berlin Anatomical Museum. His 55 separate measurements on each individual skull, while no match for the German-speaking Hungarian Aurel von Turok who took 5371 measurements of a single skull in 1890,83 does suggest a rather obsessive preoccupation.

Also significant is the way in which Fritsch chose to comment on the Zulu portraits in the text. The contrast with 'the noble Zulu' of the travel narrative could hardly be greater. The emphasis now falls not on the skillful craftsmanship involved in the elaborate hairstyling and the exoticism that it lends to the appearance of the Zulu, but rather on the strangeness of this custom: 'A national characteristic that is evident in viewing the portraits are the artistically constructed hairstyles, whose bizarre forms add much to the wild expressions on their faces'.84

There is also now little hint of nobility or empathy in the portraits of the Xhosa chiefs that Fritsch re-presented in the 'Atlas'. The lack of cultural adornment and focus on the body are the most striking features of the portraits of Xoxo, Hanta, Seyolo and Dilima. His portraits of the first counsellors, Sazini and Somi, do retain something of the cultural emphasis of the originals, but even here the effect is largely negated by the more clinical and greyer rendering of the images in copper engraved form. Fritsch's own readings of the portraits are again illuminating. In the case of Xoxo and Hanta, for example, it was the deviant development of the lips and nose that elicited textual comment: 'This table gives a good example of how important it is to have two views of the same individual. No-one would have believed that the weakly developed nose in the profile view could convert into such a hideous, almost ape-like nose in the front view ... Another characteristic of the Xhosa, that diverges from the facial configuration of the European, is the mouth, The lips are flattened and protruding (Table 6 Hanta)'.85

In the case of the Xhosa portraits, as elsewhere in the text, the European head and body serve as the model against which to compare the deficiencies of the African physique. The European is in a sense the aestheticised 'shadow archive' (to borrow Sekula's concept) that runs through the text. In the opening sections on the 'A-Bantu' (a term derived from the Nguni word 'abantu' meaning 'people', which Bleek had adopted some years earlier as a linguistic category, but was redefined by Fritsch as racial category in a physical anthropological sense),86 his argument is structured as a critique of the idealised views of the African physique presented by a 'pre-anthropological' generation, whether artists like Daniell or 'scientists' like Lichtenstein. Those who idealise the African physique in relation to that of the European, he suggested, 'should as a corrective visit the military swimming school where they would soon become convinced that the healthy, normal German, in the proportions, strength and extent of the form, in fact the entire build, is superior to the A-Bantu man'.87 This formulation points both to the influence of Fritsch's military training in remoulding his racial ideas and the extent to which German racial science was potentially buttressed by a discourse of masculinity. Gordon has suggestively argued that an obsession with African genitalia among a later generation of German anthropologists studying the Khoisan was related to a growing crisis of masculinity in Germany in the years preceding the First World War.88The portraits of the Sotho-Tswana - diversely classified as 'Basuto', 'Bamantitisi', 'Barolong', 'Gamalete', 'Maaue', 'Bakhatla', 'Bakuena', 'Babidiji' and 'Bawanketsi' - are also presented or contextualised in ways that encourage physical or craniometric readings, although these images are more diverse than those of the Zulu and Xhosa. The need for craniometric scrutiny perhaps accounts for the removal of the hat and flattening of the hair in the profile view of the 'Bakuena' man, Mozissi. Was his hair cut between the taking of the two portraits? In the case of two portraits of Ba-Khatla men, Fritsch noted in the text that: 'The crown and back of the head in the profile view provides a favourable illustration of the "hypsisteno-cephalic" skull'.89

The second section of the 'Album' presents twenty portrait images of the 'Khoikhoin', again defined as a broad racial category in a physical anthropological sense.90 Fritsch was particularly pleased with the twelve 'Bushman' portraits he was able to capture and, at times, his study adopts the language of 'salvage anthropology', one of the dominant discourses in German anthropology and ethnography at the time.91 He commented on the difficulties of procuring images of 'disappearing races' in a period of rapid transition in southern Africa. The changes that he anticipated following the discovery of gold and diamonds reinforced his view that he had 'got to know the natives [of southern Africa] in their original form. The aim was to describe the distinctive physical characteristics, external appearances and ways of life ... in order to preserve a picture for the anthropologists of today or the future before the decline of these tribes is complete'.92

The analysis that he presented in Die Eingeborenen, however, certainly prioritised 'physical characteristics' and 'external appearances' over 'ways of life'.93 Almost all of the portraits of the 'Khoikhoin' are read in the text in anatomical terms with attention drawn variously to the 'pepper-corn hair', shoulders, skull configuration, skin wrinkling or facial features. In the case of the 'Bushmen' boy, Carlo, for example, where the original photograph contrasted two items of attire - his traditional necklace and western-manufactured chain - Fritsch now drew exclusive attention to the features of the body. 'The characteristically wrinkly, leathery appearance of the skin is already evident in the 13-year old boy that I photographed near Bloemfontein' though he did concede that in this modified image it was more difficult to see 'minute details'. 'The narrow shoulders of the young boy', which have been drawn together in a way that suggests the discomfort of this teenager at being photographed and measured, are described as 'exactly characteristic [of the Bushmen] ... although the muscles have not yet taken on the character of those of the adults'.94

In the case of the old man, Boessek, Fritsch again suggested a reading that diverged markedly from the impression created by the original photograph. He interpreted the published portrait, not in terms of the strikingly exotic cluster of feathers draped over the subject's head, but as an illustration (particularly in the profile view) of the characteristic formation of the 'Bushman' nose and degree of 'prognathy'. This concept was also invented by Retzius and described the degree to which the jaw jutted forward.95

Given their framing and these textual promptings, it is hardly surprising that Fritsch's portraits were read by his contemporaries in physical anthropological terms. Wilhelm Bleek praised the 'magnificent Atlas' and drew the attention of his Cape readers to Fritsch's 'excellent photography' in that part of the work illustrative of 'the different races'.96 The reference of the leading German anthropologist of the era, Rudolf Virchow, to Fritsch's study as a 'Prachtwerk' ('Beautiful work') of great importance for the 'ethnology of the primitive peoples of South Africa' also perhaps implicitly drew attention to its more visual aspect.97 The British anthropologist, E.B.Tylor, wrote of the study more generally as an example of how 'the closer appreciation of race-types, which is now supplanting the vaguer generalities of twenty years ago, is in no small measure due to the introduction of photographic portraits'.98

From Portraits to Bones: An Aesthetic Displacement?

If his portraits of the 'natives of South Africa' became de-aestheticised when recast in the more lifeless form of copper engravings and divested of much of their cultural content, it was arguably now the bones and skeletal remains of indigenous peoples that Fritsch came to aestheticise and animate. The aesthetic dimensions of post-Enlightenment racial science have thusfar been related mainly to its idealisation of European physiology or physique. Johannes Blumenbach, whom Fritsch identified as the founder of 'our new anthropology' in the introduction to his study,99 coined the concept of a 'Caucasian' racial type based on the configuration of a single model skull found in the Caucasus. His Dutch contemporary, Pieter Camper, invented a racial marker, the 'facial angle' (which described the angle that a line drawn from the chin to the top of the forehead forms with a horizontal line at the base of the chin) as the basis for a scale of beauty that ran from the ape and Negro through contemporary European peoples to an ideal form represented in Greek sculpture.100 Apart from his borrowings of these two concepts in his study, there is much evidence of Fritsch aestheticising the European form, perhaps best exemplified by the symbol of the 'healthy, normal' German body at the 'military swimming school'.

But a close analysis of the discourse of Die Eingeborenen also suggests that Fritsch, in a rather macabre displacement, now came to aestheticise the dead rather than the living, the bones rather than the portraits.101 Already in his travel narrative, he made reference to a skull that he had dug up in July 1864 in the Orange Free State as 'pretty' ('die schonen Schadel').102 He now wrote in terms of the 'impressions' or 'characteristics' made on a viewing of the photographed skulls that were presented in his study. There is a sense in which the bones became animated and took on some of the life divested from the portraits, as they are described as either 'graceful' or 'ungraceful', or as bearing a certain 'character', usually that of a lack of civilisation.103 It was not too great a leap from a language of 'pretty' skulls and 'graceful bones' to the sending of Herero skulls on postcards from Namibia to Germany in later decades.104

'Groping Towards a Visual Expression of Anthropological Method'105

In the sections above I have analysed the 'ethnographic' portrait photographs that Fritsch took during his expedition through southern Africa between 1863 and 1866 and the way in which these photographs were re-presented as physical 'anthropological' portraits in Die Eingeborenen Sud-Afrikas in 1872. I have also suggested how we might make sense of this shift. Apart from the technical modifications involved (and their foreseen or unforeseen consequences), the change in emphasis has been related to changes in Fritsch's personal experience and intellectual context. There are hints that his military involvements in 1866 and 1870 encouraged the development of more strongly nationalist sentiment as the young and somewhat romantic adventurer in Africa, barely twenty-six years of age when he set out on his travels, became the conservative German citizen imbued with greater chauvinism. It is surely not coincidental that he opens his 1872 study on a stridently nationalist note: 'We live in a great time: the German nation has been proudly forged through difficult struggle. The author himself has willingly followed the call of his nation'.106

But more fundamentally, the shift has been related to his professional integration into an emergent German, and especially Berlin, anthropological community. He came to establish his academic career through his appointment to the Anatomy Department at Berlin University and his integration into the Berlin Society in 1872. The intellectual context within which I have analysed his represented portrait images then has been that of a Berlin anthropological commu-nity-in-the-making, newly institutionalised and growing in self-confidence, where physical anthropology assumed a dominant role as the diffuse earlier boundaries between physical and cultural studies had come to harden.

But it is also necessary to locate this intersection between photography and anthropology in Fritsch's work in more theoretical terms. As Edwards has imaginatively proposed, the emergence of the genre of 'racial type' photography during the 1860s and 1870s is best conceptualised in terms of a quest in the relatively new discipline for a distinctive methodology:

[P]hotography was being extensively used in the recording of anthropological material at a time when anthropologists were seriously concerned with improving the quality and the quantity of their data and strengthening the scientific base of their discipline's method ... It was in reaction to this [the previously] unstructured use of visual material and as a response to the growing body of 'method' in anthropology that attempts were made to exert greater intellectual control over visual data so that the 'reality' of photographic recording could be usefully and systematically harnessed to anthropological study.107

It was precisely in order 'to exert greater intellectual control' over the visual data that he had earlier accumulated, in a very different spirit, that Fritsch selected, arranged and re-framed his portraits of the 'natives of South Africa' in his 1872 anthropological study. There is little doubt that Fritsch was keenly preoccupied with issues of anthropological method at the time. In March 1870 in his only significant contribution to the meetings of the Berlin Society in its very earliest years, he spoke about the methodological implications of two new technologies - photography and the Lucaesian apparatus - for the fledgeling discipline. While there were scientific problems with both, he argued that through careful and self-conscious use the anthropologist could minimise the inaccuracies involved.108

His extensive commentary in the introduction to the volume of portraits on the scientific principles that guided the taking of his photographs and his anxiety regarding the process of conversion into copper engravings need to be read in precisely this light. Fritsch advocated strict consistency in the taking of 'racial type' photographs with lighting from behind, standardised distancing between the camera and the subject being photographed, but in a way that ensured enough distance to minimise 'perspectival shortening', and the maintainence of level or horizontal views.109 He was also preoccupied with issues of method in his photographing of skulls which he did with the help of the Lucaesian apparatus.110

It was these groping towards a disciplinary methodology rather than an aversion to the theory of evolution that prompted his critique of Haeckel. Fritsch was less bothered than many of his colleagues by Haeckel's evolutionary ideas.111What he did object to was the cavalier way in which Haeckel used profile portrait views as the only visual evidence on which to base his generalisations: 'For these and many other portraits [in Die Eingeborenen] it is important to note how often the two views [front and profile] do not correspond ... This observation provides a weighty warning against the use, or rather misuse, that Haeckel has made of profile illustrations ... It is unjustifiable on the basis of profiles alone to draw conclusions regarding evolutionary development'. Here he made footnoted reference to the 'caricatured' profile portraits of the 'Kaffer' and 'Hottentot' in Haeckel's controversial and recently published study Naturliche Schopfungsgeschichte (A Natural History of Creation).112

Fritsch seems to have regarded his coupling of front and side profile portrait views as one of his most important methodological innovations. It may indeed have been unusual at the time. He commented frequently in his physical anthropological readings of the portraits on the potentially discrepant conclusions that could be drawn from front and side perspectives, insisting that both views were necessary to achieve a scientifically balanced impression.

Fritsch's methodological stamp was also evident in the photographic section of a lengthy report submitted by the Berlin Society to the Prussian Navy in 1872. The report presented a comprehensive statement of contemporary anthropological method in its provision of instructions to naval personnel about the appropriate means of collecting anthropological data. The subsection on photography outlines in great detail how to take scientifically accurate anthropological photographs of 'native' peoples - both in portrait and full body form.113 It is best read as a fusion of Fritsch's ideas about the taking of scientific portraits (the echoes of his own study are direct) and those set out by Huxley in 1869 for the taking of scientific full body portraits.114

In reconsidering Fritsch's anthropological study (at least in part) as a methodological engagement, it is also appropriate to locate it in terms of the numerous contemporary projects to compile collections of visual images of 'racial types'. For Fritsch certainly envisaged his portrait 'gallery' (to use his own term) as a kind of catalogue of visual information about 'racial types' in a specific regional context. His rather grandiose designation of the collection as an 'Atlas' and his apologetic attitude towards the absence of any representative Damara and Herero portraits115 are best understood in view of this quest to demarcate a new visual field.

As such Fritsch's collection of portraits represents, in conception at least, a project comparable to that of The Peoples of India (1868-), the Huxley project to compile a catalogue of representative "racial types" from throughout the British Empire (1869-71) and the effort of his German anthropological colleague Carl Dammann to gather and collate visual data on all 'racial types' within a single volume (1870-5).116 But, as Edwards demonstrates, the scientific rigour of these projects varied considerably in a period in which 'racial type' photography was still very loosely conceived. If we think about Fritsch's 'Atlas' of portraits in these terms, its methodology is far closer to the assumptions informing Huxley's very rigidly anthropometric schema than the relatively ad hoc, unsystematic methodological principles that informed the publication of his German contemporary, Carl Dammann. For Fritsch, as I have argued, eschewed a geographic arrangement of his portrait photographs in favour of a hierarchical (and perhaps Darwinian) ordering of 'racial types'. His portraits, while clearly not nearly as invasive as those taken along the lines set out by Huxley, were selected and framed in such a way that they compelled attention primarily to the physical rather than the cultural, to the body rather than dress or adornment.

1 This paper owes much to Patricia Hayes and her searching critiques of my earlier writings and presentations on Fritsch.

2 See especially E.Edwards, ed., Anthropology and Photography, 1860-1920 (New Haven and London, 1992). On the methodology of Malinowski and British social anthropology in the twentieth century, see A.Kuper, Anthropologists and Anthropology(London, 1973).

3 M.Blackman, 'Introduction' in M.Banta and C.M.Hinsley, From Site to Sight: Anthropology, Photography and the Power of lmagery (Cambridge, Mass., 1986), 11.

4 The concept of 'racial type' was, Edwards argues, still relatively loosely defined during this period and more widely used than in a strictly biological sense. E.Edwards, 'Photographic "Types": The Pursuit of Method', Visual Anthropology, 3 (2-3), 1990, 235. I will return to the very important theoretical arguments of this article in much greater detail later in the paper.

5 On the importance of 'salvage logic' in contemporary British anthropology, see E.Edwards, 'Introduction' in E.Edwards, ed., Anthropology and Photography, 3-17 and in German anthropology and its connections to ethnographic collecting, see H.G.Penny, 'Cosmopolitan Visions and Municipal Displays: Museums, Markets and the Ethnographic Project in Germany, 1868-1914' (Ph.D., University of Illinois, 1999), chapter two.

6 J.Tagg, The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories (Massachussetts, 1988), 39.

7 A.D.Bensusan, Silver Images: History of Photography in Africa (Cape Town: Howard Timmins, 1966).

8 M.Banta and C.M.Hinsley, From Site to Sight: Anthropology, Photography and the Power of Imagery, 11, 46.

9 E.Edwards, 'Photographic "Types"', Visual Anthropology, 3 (2-3), 1990, 243.

10 A.Sekula, 'The Body and the Archive' in R.Bolton, ed., The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography (Massachussetts, 1989), 345.

11 J.Tagg, The Burden of Representation, 5, 11.

12 'South Africa' was at this time, of course, simply a broad geographical designation and therefore includes what we would today refer to as 'southern Africa'.

13 A.Sekula, 'On the Invention of Photographic Meaning' in V.Burgin, ed., Thinking Photography (London, 1982), 93-4. Fritsch's photographs, while reproducible, were (as we shall see) not easily convertible into an accessible published form.

14 The terms 'ethnographic' (or 'ethnological') and 'anthropological' were loosely defined during the 1860s, but by the early 1870s came to demarcate the boundaries between the cultural and the physical more clearly, in the German (and continental) anthropological traditions at least. (G.W.Stocking, 'Introduction' in G.W.Stocking, ed., Bones, Bodies and Behaviour: Essays on Biological Anthropology(London and Madison,1988), 9).

15 B.Massin, 'From Virchow to Fischer: Physical Anthropology and "Modern Race Theories" in Wilhelmine Germany' in G.W.Stocking, ed., Volksgeist as Method and Ethic: Essays on Boasian Ethnography and the German Anthropological Tradition (Madison, 1996), 82.

16 On early German anthropology 'as medicine', see R.Proctor, 'From Anthropologie to Rassenkunde in the German Anthropological Tradition' in G.W.Stocking, ed., Bones, Bodies and Behaviour, 138-79, though his subsequent arguments for strong continuity between German physical anthropology of the mid-late nineteenth century and Nazi racial science is very persuasively demolished by the evidence and arguments presented in B.Massin, 'From Virchow to Fischer', 88-95. On the emergence of the cultural sciences in Germany in the middle decades of the nineteenth century, see W.D.Smith, Politics and the Sciences of Culture in Germany (New York and Oxford, 1991).

17 This was also true of the leading anthropologists of the next generation like Felix von Luschan and Eugen Fischer.

18 This is derived from the list of publications in the appendix to G.Fritsch, A German Traveller in Natal: Three Chapters from 'Drei Jahre in Sud-Afrika' (Durban, 1992; translation by G.Little) and G.Fritsch, Drei Jahre in Sud-Afrika: Reisekizzen nach Notizen des Tagesbuchs Zusammengestellt (Breslau: Ferdinand Hirt, 1868), viii.

19 J.Silvester, P.Hayes and W.Hartmann, '"This Ideal Conquest": Photography and Colonialism in Namibian History' in W.Hartmann, J.Silvester and P.Hayes, eds., The Colonising Camera: Photographs in the Making of Namibian History (Cape Town, 1998), 10.

20 For an analysis of Chapman's mission and stereographs, see M.Godby, 'The Interdependence of Photography and Painting on the South West Africa Expedition of James Chapman and Thomas Baines' (this edition) and S.Kliem, 'The Eye as Narrator in the Nineteenth Century Expedition Writing and Photography of James Chapman, 1860-64' (M.A. thesis, University of the Western Cape, 1995). Fritsch evidently admired Chapman, praising his (favourable) ethnographic comments about the 'Bushmen' and complimenting his photographic experiments under very difficult circumstances. He included a woodcut version of Chapman's stereograph of the 'Damara' in his scientific study and remarked on its greater veracity than Thomas Baines's 'caricatured' versions of the figures in the same scene. (G.Fritsch, Die Eingeborenen Sud-Afrikas, vol. 1, 214)

21 Another important aspect of his 'anthropological' mission was the collection of bones. For more evidence of his collection of skeletal materials, see A.Bank, 'Racial Science as Cultural Encounter: Gustav Fritsch's Studies of the Indigenous Peoples of Southern Africa, 1863-66' (Paper presented at the 'Forgotten Histories, Public Histories Conference', University of Namibia, August 2000).

22 I am grateful to Christine Stelzig at the Berlin Museum of Ethnology for this information sent via e-mail correspondence, 2 August 2000. The Fritsch photographs are contained in albums in the African Department of the Berlin Museum of Ethnology. I have not yet had the opportunity to consult this collection of his photographic originals and my analysis of the original photographs in this paper therefore rests on the South African Library's collection and the inferences that I can draw about the Berlin portraits from his later published versions of them.

23 G.Fritsch, Drei Jahre in Sud-Afrika, Fig. 28, 165.

24 This is the photograph of a 'Koranna-Hottentot' in K.Schwabe, Im Deutschen Diamantenlande: Deutsch-Sudwestafrika von der Errichtung der Deutschen Herrschaft bis zur Gegenwart, 1884-1910 (Berlin, 1909), 5. The decontextualised nature of Schwabe's use of Fritsch's portraits is only highlighted by the fact that Fritsch did not travel in Namibia, the area of focus of Schwabe's study. The other photograph where the chair is visible in the background is that of 'Boessak, Bushman, Bain's farm, Orange Free State' reproduced in K.Schoeman, The Face of the Country: A South African Family Album, 1860-1910 (Cape Town, 1996), 18.

25 E.Edwards, 'Photographic "Types": The Pursuit of Method', 253.

26 G.Fritsch, Drei Jahre in Sud-Afrika, 32.

27 H.Deacon, ed., The Island: A History ofRobben Island, 1488-1990 (Cape Town: David Philip, 1996), 54.

28 G.Fritsch, Drei Jahre in Sud-Afrika, 32.

29 The elaborate hairstyling practices of the Zulu became a relatively popular subject for ethnographic photographers in Natal in subsequent decades. See, for example, the photographs taken (or donated) by Captain Walmesley that were kept in the Grey Ethnological Album, South African Library, 38-41 and J.E.Middlebrook's photograph, 'A Study in Hairdressing' in V.L.Webb, 'Nineteenth-Century Photographs of the Zulu', African Arts, Jan. 1992, 25 (1).

30 G.Fritsch, Drei Jahre in Sud-Afrika, 190. Here are elsewhere in this paper the translations from the German are my own.

31 The South African Library collection also contains a side profile view of a 'Tambuki' man, "Kwadana", that Fritsch photographed at Shiloh wearing a jacket and shirt.

32 'Proceedings' ('Verhandlungen'), 14 June 1873 Session, Zeitschrift fur Ethnologie,, vol. 5, 1873, 105.

33 See S.Kliem, 'The Eye as Narrator', 31; M.Godby, '"Some Little Bit of Effective Representation"', 62. Although the responses of Africans to being photographed varied considerably and may have been more complex than Chapman or Fritsch suggest in their travel narratives, there is abundant evidence to indicate that many Africans viewed the alien and imposing photographic technology with some trepidation.

34 The reconstruction of the role of intermediaries by reading between the lines of the travel narrative is one of the many absorbing aspects of Fabian's recent study of European (mainly German) explorers in central Africa during the late nineteenth century. See J.Fabian, Out of Our Minds: Reason and Madness in the Exploration of Central Africa (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2000), 23-51.

35 G.Fritsch, Drei Jahre in Sud-Afrika, 280.