Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.114 n.2 Pretoria Feb. 2024

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2023.v114i2.1334

RESEARCH

Community perceptions of community health worker effectiveness: Contributions to health behaviour change in an urban health district in South Africa

L S ThomasI; Y PillayII; E BuchIII

IMMed (PHM), PhD; Gauteng Department of Health; School of Health Systems and Public Health, University of Pretoria; School of Public Health, University of the Witwatersrand, Gauteng, South Africa

IIPhD; Clinton Health Access Initiative, Pretoria, South Africa

IIIMB BCh, FFCH (CM)(SA); School of Health Systems and Public Health, University of Pretoria and Colleges of Medicine, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Community health worker (CHW) programmes contribute towards strengthening adherence support, improving maternal and child health outcomes and providing support for social services. They play a valuable role in health behaviour change in vulnerable communities. Large-scale, comprehensive CHW programmes at health district level are part of a South African (SA) strategy to re-engineer primary healthcare and take health directly into communities and households, contributing to universal health coverage

OBJECTIVE: These CHW programmes across health districts were introduced in SA in 2010 - 11. Their overall purpose is to improve access to healthcare and encourage healthy behaviour in vulnerable communities, through community and family engagements, leading to less disease and better population health. Communities therefore need to accept and support these initiatives. There is, however, inadequate local evidence on community perceptions of the effectiveness of such programmes

METHODS: A cross-sectional descriptive study to determine community perceptions of the role and contributions of the CHW programme was conducted in the Ekurhuleni health district, an urban metropolis in SA. Members from 417 households supported by CHWs were interviewed in May 2019 by retired nurses used as fieldworkers. Frequencies and descriptive analyses were used to report on the main study outcomes of community acceptance and satisfaction

RESULTS: Nearly all the study households were poor and had at least one vulnerable member, either a child under 5, an elderly person, a pregnant woman or someone with a chronic condition. CHWs had supported these households for 2 years or longer. More than 90% of households were extremely satisfied with their CHW; they found it easy to talk to them within the privacy of their homes and to follow the health education and advice given by the CHWs. The community members highly rated care for chronic conditions (82%), indicated that children were healthier (41%) and had safer pregnancies (6%

CONCLUSION: As important stakeholders in CHW programmes, exploring community acceptance, appreciation and support is critical in understanding the drivers of programme performance. Community acceptance of the CHWs in the Ekurhuleni health district was high. The perspective of the community was that the CHWs were quite effective. This was demonstrated when they reported changes in household behaviour with regard to improved access to care through early screening, referrals and improved management of chronic and other conditions

The role of the 'community' in community health worker (CHW) programmes across developing countries is often not clear.

The World Health Organization states that communities should be vested in such programmes,[1] yet community relationships, their views and perceptions of local CHW programmes are not well documented.[2]

CHW programmes can contribute to improvements in population health.[3] Arvey et al.[4] argue that while the potential of CHW programmes to improve health outcomes is evident, the details on how they make a difference is not well described in studies. This could be part of the 'core elements' determining effectiveness of CHW programmes, one of which is changing health behaviour of communities through consistent and sustained interactions at individual, household and community levels. The contextual factors in terms of community perceptions and local embeddedness may play a pivotal role in understanding some of the factors influencing CHW programme performance.[5] Understanding these 'softer', more intangible issues may provide greater insights[6] on how CHW programmes perform and are managed.

Kok et al.[7] conducted a systematic review of studies exploring the role of contextual factors on CHW performance. They focused on English publication studies in low- and middle-income countries. They found that few studies explored contextual issues, which are often complex and interwoven. Those that had were summarised into factors such as community context (sociocultural, gender norms, safety and security, disease-specific stigma and education levels of target populations), economic and environmental contexts as well as health system policy and practice contexts (clear CHW policy, CHW job descriptions, political support, resources, decentralisation and decision-making, governance structures). Future health systems research on CHW programmes should include more of these contextual factors.

The unique positioning of CHWs within communities plays a pivotal role in influencing performance. A qualitative study on the health extension workers (HEWs) in Ethiopia explored this in detail.[8] This study, conducted by Kok et al.,[8] looked at how relationships between the HEWs, the community and the health services evolved. They found that where HEWs were recruited by and from the community, there was greater trust in the relationship. Community involvement was more explicit and better than the support from the health service. The latter was found to be more top-down supervision with poor referral, support and training; this constrained the relationship between the HEWs and the health services. Although the study had a number of limitations, role clarification at all levels, better supervision, support, training and community involvement were reinforced.

De Vries and Pool[9] conducted a systematic literature review of 32 published studies, mainly from low-income countries. They explored the extent to which the community invested in a CHW programme. Their study looked at various community dynamics regarding involvement in planning, recruitment, and training and implementation support of the CHW programme. They found a gap in the literature about documentation on such community involvement. There were scant quantitative data on this topic, despite many qualitative studies detailing the importance of community relationships. The authors acknowledge that since most of the studies reviewed were from low-income countries in the first place, community capacity and resources to support CHW programmes would likely have been minimal at the outset.

This is an important consideration for the real-world study setting in the Ekurhuleni health district. All the CHW teams in Ekurhuleni were functioning in vulnerable and poor areas, where the term 'community' may not be functionally accurate within the urban sprawl. While there were ward councillors in these areas, the social cohesion of some of the residents in these areas was usually not evident, and where it was, it was through less formal structures such as churches, schools, traditional healers and the like, with limited 'community' resources to support CHW programmes. This Ekurhuleni study explores the perception of individual household members supported by CHWs, the perceived effectiveness of the CHWs and the role these community members felt they should have, all important determinants of community involvement.

The CHW programme in Ekurhuleni, an urban district in South Africa (SA), is considered large-scale and comprehensive, and was implemented in 2010 - 11. Since then, over 1 000 CHWs, functioning in 178 teams, support approximately 280 000 vulnerable households in the district. Each CHW supports 250 households; existing CHW teams consist of 6 - 10 CHWs managed by a nurse outreach team leader (OTL), looking after approximately 1 million residents from poor areas in Ekurhuleni. These CHWs in Ekurhuleni provided comprehensive care, sustained over many years, for maternal and child health issues, infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases and social issues in allocated households.[10] The care included early screening and detection of health problems, referrals to higher levels of care and ensuring clients accessed care and control of diseases timeously, and over time were found to have improved population health outcomes in areas supported by the CHWs in Ekurhuleni.[3]

Methods

The objectives of this cross-sectional descriptive study were to explore what household members felt about the CHW teams supporting their households, including their own involvement in enabling these teams.

The study setting is the Ekurhuleni health district, an urban area in SA.

The study population was 56 000 households with >60% coverage of CHW teams. Using the Raosoft sample size calculator, 95% confidence level, a 5% margin error, 50% response distribution and a 5% buffer, an estimated 400 households needed to be sampled. Of the poor and vulnerable households identified from diverse parts of the district, 417 households were selected for the study.

Catchment area maps were available, and a random spot on the map was selected daily as a starting point. The field workers went to every fifth household until the required number of households were reached. If household members were not available, one attempt was made to revisit the household, and if still not available, telephonic contact was attempted. If this too was unsuccessful, replacement households were used in the opposite direction from the unavailable house.

These households were supported by their CHW teams for 2 years or longer. The households had an average monthly income less than USD150, and were therefore considered poor households. They had to have at least one vulnerable member, either a child under 5, an elderly person, a pregnant woman or a member with a chronic condition to be included in the study.

The household head provided consent, and was interviewed by trained, independent, retired nurses using interviewer-administered questionnaires. The questions were on duration and frequency of CHW visits, CHW attributes found important and the household head's experiences with these visits. The questionnaire was developed by the research team specifically for this study and was piloted and tested before use.

Data were collected in May 2019. Confidentiality was ensured by removing all personal information during the final analysis.

Data analysis was descriptive, and based on frequencies of the above data elements.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Pretoria Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee (ref. no. 581/2018). The Ekurhuleni health district consented to the study.

Results

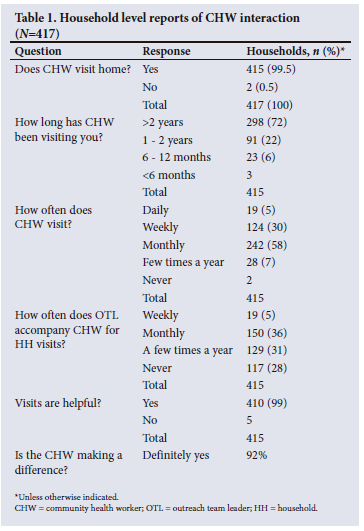

Of the 417 vulnerable households included in the study and supported by district CHWs, 83% were headed by females. Nearly all were indigent South Africans earning <USD150 per month and had lived in the area for >5 years.[3] As can be seen from household head interviews, as shown in Table 1, the CHWs visited 72% of sampled households for >2 years. Visits were regular, either weekly or monthly. These visits were perceived by 99% of the households to be helpful.

In closed and open-ended questions to the household members, they reported that CHWs helped them largely through improving adherence support, providing health education and ensuring access to healthcare.

Fig. 1 and the quotes below from household members illustrate how CHWs made a difference to them.

'They check us, teach us about the importance of clinic visits and solve some of the questions we have.'

'Learnt that I can go to clinic whenever I need help. With education we learn a lot.'

'By trying to apply for food vouchers for me.'

'Take me to clinic to immunise child.'

'She is always taking care of me, encouraging good nutrition, and advises me not to default.'

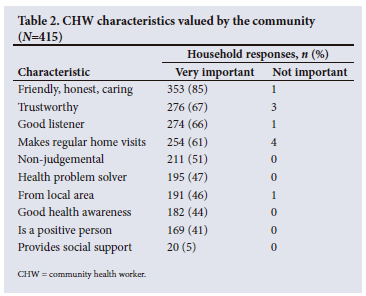

Household respondents also stated that what they valued the most about their CHWs was their friendliness, honesty, caring attitude, trustworthiness, being a good listener, being non-judgemental and being able to solve their health problems. They also appreciated that the CHW was from the local area.

Individual CHW characteristics most valued were friendliness, honesty and caring traits, listed in Table 2.

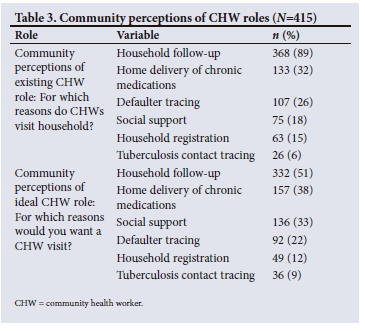

When asked what the roles of CHWs in households were and should be, household members considered household follow-ups to be most relevant to them. Defaulter and contact tracing for all health conditions were also perceived as important, but not as high as regular interactions with the households. Provision of social support services was considered a significant role for CHWs (Table 3). Home delivery of chronic medication was also considered an important role.

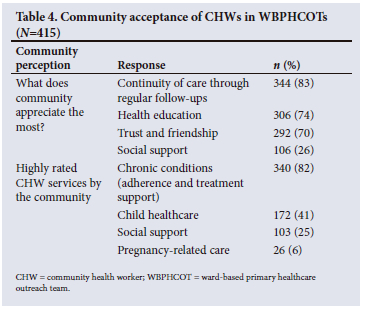

These findings are reiterated in Table 4, which showed that the community appreciated the regular follow-up and continuity of care, especially for chronic conditions. The provision of health education and social support by CHWs was similarly well appreciated. In addition, the friendship and relationship with CHWs was treasured by the community.

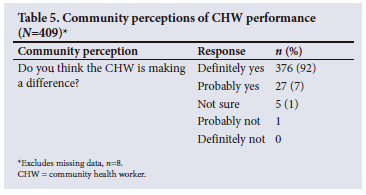

More than 90% of household respondents felt the work of CHWs was making a difference in their lives, as shown in Table 5.

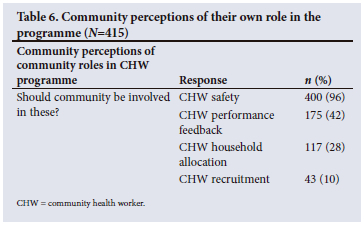

Household members interviewed had definite ideas of their role as communities concerning CHW teams (Table 6). The community stated that they had a role to play regarding ensuring safety of CHWs within the community, in giving feedback on team performance and in deciding which households should be supported by CHWs.

Discussion

The findings from this study showcase that 92% of household members, representative of the community supported by CHWs in the Ekurhuleni health district, SA, were satisfied with the work of the CHWs. What 83% of household members appreciated the most from their interactions was the continuity of care provided by CHWs, the health education and social support services, through a relationship built over time. Although social support is part of welfare and not health services and therefore not routinely quantified or reported on, it was clear that CHWs played a role in enabling communities to access psychosocial care.

Households in this study felt that CHWs were effective, which is an important consideration for scale-up and sustainability of public health interventions of this nature.

There needs to be more local and global evidence of CHW programmes' effectiveness, especially the context in which some programmes do better than others, or vice versa. There is also insufficient global evidence on how CHWs influence health behaviour change in communities, if at all.[11] It is not clear if this is through better community accountability to CHW programmes, or positive relationships between households and CHWs, or both.

Countries tend to copy each other, referred to as isomorphic mimicry, assuming that what works well somewhere will work well in their own country. However, context matters. It is difficult to develop a one-size-fits-all approach for certain soft factors such as community embeddedness and health system support. There are some things that can be 'copied' or standardised, such as training, remuneration, resources and equipment, but the softer, less tangible issues are more complex and can make or break CHW programmes. In this article, these softer issues refer to community perceptions and values of how CHWs should perform and are performing. There is not much global evidence on public/community views on CHW programmes,[12] and the findings from our article provide these important viewpoints.

The findings of our article show that CHWs in this district programme were perceived by the community to influence some behaviour change (Fig. 1) through early access to care, early diagnosis of chronic disease and adherence in maternal, child and chronic conditions. This improved diagnosis and management of maternal and child health outcomes as well as chronic disease control.[3] This is primarily because of the long-term relationship built between the CHW and the household; 72% of households had been supported by CHWs for 2 years or longer. Notably, 85% of household members cherished the friendship and good individual traits of CHWs. These relationships strengthen when CHWs are embedded and are part of the community.[13] Mohajer and Singh[13] postulate that such community embeddedness and accountability is possible only if CHWs are mainly volunteers and not paid. Those who are paid are more loyal to their employer and may not put the community's interest first. Therefore, the authors propose two cadres, those who volunteer and those who are paid. However, in the SA context, with high unemployment, this is not a viable option. Indeed, in our study in Ekurhuleni, the CHWs were not volunteers but paid, and were part of the formal health system, and they were recruited from the same communities where they were expected to work, and in some ways this reinforced their community embeddedness.

Our results showed that while 10% of households interviewed felt that they should be involved in CHW recruitment, the majority did not feel this was a major role; we postulate that this may have been because the community was aware of the integration of CHWs into the formal health system in Ekurhuleni. Brown et al.[14] test and discuss selection and recruitment processes in two other African countries. A contextual approach with a combination of selection processes may be more appropriate in different settings. In the Ekurhuleni (and indeed the SA) context, most CHWs had worked in non-governmental organisations before, and therefore had some prior learning, but little formal schooling and poor literacy levels. Within this context, their ability to do certain tasks, brief personal interviews and community feedback may be better ways of selecting them than subjecting them to panel-based interviews or written tests, so there certainly is a role for communities in their recruitment. Community accountability was still evident in Ekurhuleni; in our discussions with household members, they shared how CHWs went the extra mile, did more than was expected and empowered the community in a number of different ways, including improving access to social support services, as shown in other studies too.[2] Our findings, and those of others,[2,15] show that community accountability and embeddedness can also be achieved by paid CHWs who are part of the health system. LeBan et al.[16] postulate that good community support is essential for large-scale CHW programmes to perform well;[16] the findings from our study illustrate that this was the case in Ekurhuleni.

Studies have shown that public satisfaction with CHW programmes is an important element in motivating CHWs and in sustaining CHW programmes.[17] In our findings, we demonstrated that >90% of households said they benefited from the frequent interactions with their CHWs during routine team visits (at times supported by their OTLs). This enabled greater buy-in and support from the community. According to Oliver et al.,[18] the perceptions of the community of team performance are also predictors of CHW programme effectiveness, and therefore important to determine. In addition, the type of services offered by CHWs and OTLs has an effect on community satisfaction. A randomised controlled trial comparing households with and without CHW support showed that where CHW programmes had a strong maternal health component, women in the community rated these services highly.[19]

The findings in our study showed that the configuration of the comprehensive CHW activities in Ekurhuleni, by providing continuity of care through regular follow-up visits, health education, social support services as well as the trust and friendship provided by the CHWs to the household members, was valued by the community. These would have contributed to the benefits experienced by the households in the same manner as found by Mohajer and Singh.[13]

The findings in our study illustrate good community appreciation of a programme that was perceived as beneficial; this is an important finding adding to local and global evidence in this regard.

Unpacking the community's role concerning CHW teams illustrated other important points. Communities (42% of households) felt that they should give feedback about CHW performance. This is an important component of programme accountability within the context of community embeddedness. If communities are structured and coherent, they can play a vital role in selection, feedback and ensuring accountability. However, in less-developed communities such as in urban informal townships, this may not be the case,[9] and often there is nepotism during recruitment or a lack of understanding of the sort of skills a CHW should have. As roles of CHWs become increasingly varied and fall under the state, shifting away from volunteer work to more formal roles within health systems, their identification, selection and recruitment has to be responsive to these reviewed roles and responsibilities.[20] In Ekurhuleni at the time of our study, the CHWs were paid contracted staff who in 2020 were made permanent staff. With CHWs now permanent staff, the crucial dynamic will be to determine how to position CHWs in the unique interface between health services and the community. Community governance structures such as ward committees, clinic committees and the like are crucial in supporting this unique positioning.

The local ward/municipal councillor plays an important community role in facilitating the teams' entry into the community. Ward councillors or other local community leaders are respected, and when they introduce CHWs at local gatherings, the community is more likely to trust and engage them. This improves community embeddedness over time.[11] The community themselves felt they had a big role to play in ensuring the safety of CHWs; this is an important finding with 96% of households indicating so. SA has high crime statistics, especially in informal, urban poor communities.[21] CHW safety was a concern that was considered in the initial years of implementation; pairing CHWs together seemed to help. The community also volunteered to watch out for CHWs and escort them through unsafe parts of the community, and there were no major incidents as a result. However, in 2019, there were two incidents where a group of CHWs were sexually assaulted and robbed. Mirroring an alarming trend globally,[22] there is an increase in violence towards health workers in the country, in ambulances, clinics and in hospitals. This requires greater community involvement, and the opportunity this study finding provides is just that: a chance to engage communities further in how they can ensure better safety for CHWs and other health workers.[23]

Health systems are complex and constantly evolving. CHWs are an important component of such complex, adaptive systems. And, while the usual 'hardware' elements influencing performance are reasonably documented in health system support in the form of resources, training, supervision and so on, some of the more intangibles, especially community perceptions, referred to by Kok[6] as 'software' elements, are often not as clearly understood.

Often, these softer issues are less obvious in the early stages of implementation. The findings from our article illustrate high community perceptions of effectiveness and acceptance, but interestingly, neither of these were in place in the early years of implementation of the district CHW programme. As households started seeing changes in their neighbours' or friends' lives, they started understanding the role of CHWs more. These small successes led to more credibility and value in the programme, and as the successes snowballed, so did the support from the communities. There was sufficient decision-making ability in the district under review to ensure that these soft issues could be used to mobilise community support for larger-scale implementation in the district.

Although not part of the findings of this study, our experience has shown that an important element the CHWs brought into the community was the opportunity for community participation. This is an important component of primary healthcare that is often challenging to address. Clinic committees certainly help, but CHW teams such as those in Ekurhuleni are uniquely positioned to enable community entry, engagement and participation. By engaging local community leaders and structures and the broader community on local health issues as well as broader social and developmental challenges, CHWs were able to create opportunities for the community to participate in their own growth and development. This view coincides with the view of McCollum et al.[24] when describing how CHW programmes can address equity challenges in their communities.

Limitations

Areas of CHW support could not be randomly assigned, as this was a real-world study setting. This was mitigated by selecting households from different parts of the district.

Recall bias when interviewing only the household head was mitigated through the use of trained fieldworkers (retired nurses) who first verified that the interviewee had information on household members, and if not, another household was selected.

Conclusion

Community perceptions, acceptance and support are good predictors of effectiveness of CHW programmes. This study showed that the community was deeply appreciative of CHW teams in Ekurhuleni. They accepted and recognised the valuable role CHW teams had in improving their health, contributing to improved changes in health behaviour in these households. The community did feel that CHWs were making a difference, and felt they were effective. We found that the community wanted to be involved in the district CHW programme, especially in ensuring the safety of the CHWs and in giving feedback on performance. More research is still needed on how community cohesion can be strengthened and how members can be engaged further, especially in urban areas. Community acceptance and ongoing support are important for sustained performance of CHW programmes; this also reflects the strengths of the local implementation context in Ekurhuleni.

Availability of data and material: Data can be made available on reasonable request and/or after all related publications are concluded.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. All CHW teams in Ekurhuleni.

Author contributions. LT was responsible for data extraction and analysis. LT and EB developed the concepts and methodology, and concluded the analysis and write-up. YP gave input and corrections to the final manuscript.

Funding. Public health sector and University of Pretoria staff grant for research and publication costs.

Conflicts of interest. The principal investigator is employed by and responsible for the CHW programme in Ekurhuleni; this is part of her doctoral work.

References

1. World Health Organization. Community health workers: What do we know about them? The state of the evidence on programmes, activities, costs and impact on health outcomes of using community health workers. Geneva: WHO, 2007. [ Links ]

2. Taylor RK. An exploration of the mechanism by which community health workers aim to bring health gain to service users in England. UK: University of Birmingham, 2015. [ Links ]

3. Thomas LS, Buch E, Pillay Y, Jordaan J. Effectiveness of a large-scale, sustained and comprehensive community health worker program in improving population health: The experience of an urban health district in South Africa. Hum Resour Health 2021;19(1):153. [ Links ]

4. Arvey SR, Fernandez ME. Identifying the core elements of effective community health worker programs: A research agenda. Am J Public Health 2012;102(9):1633-1637. [ Links ]

5. Christopher JB, le May A, Lewin S, Ross DA. Thirty years after Alma-Ata: A systematic review of the impact of community health workers delivering curative interventions against malaria, pneumonia and diarrhoea on child mortality and morbidity in sub-Saharan Africa. Hum Resour Health 2011;9:27. [ Links ]

6. Kok MC, Broerse JEW, Theobald S, Ormel H, Dieleman M, Taegtmeyer M. Performance of community health workers: Situating their intermediary position within complex adaptive health systems. Hum Resour Health 2017;15(1):59. [ Links ]

7. Kok MC, Kane SS, Tulloch O, et al. How does context influence performance of community health workers in low- and middle-income countries? Evidence from the literature. Health Res Policy Syst 2015;13(1). http://health-policy-systems.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12961-015-0001-3 (accessed 12 July 2018). [ Links ]

8. Kok MC, Kea AZ, Datiko DG, et al A qualitative assessment of health extension workers' relationships with the community and health sector in Ethiopia: Opportunities for enhancing maternal health performance. Hum Resour Health 2015;13:80. [ Links ]

9. De Vries DH, Pool R. The influence of community health resources on effectiveness and sustainability of community and lay health worker programs in lower-income countries: A systematic review. PloS ONE 2017;12(1):e0170217. [ Links ]

10. Thomas LS, Buch E, Pillay Y. An analysis of the services provided by community health workers within an urban district in South Africa: A key contribution towards universal access to care. Hum Resour Health 2021;19(1):22. [ Links ]

11. Scott K, Beckham SW, Gross M, et al. What do we know about community-based health worker programs? A systematic review of existing reviews on community health workers. Hum Resour Health 2018;16(1):39. [ Links ]

12. Maher D, Cometto G. Research on community-based health workers is needed to achieve the sustainable development goals. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2016. [ Links ]

13. Mohajer N, Singh D. Factors enabling community health workers and volunteers to overcome socio-cultural barriers to behaviour change: Meta-synthesis using the concept of social capital. Hum Resour Health 2018;16(1):63. [ Links ]

14. Brown C, Lilford R, Griffiths F, et al. Case study of a method of development of a selection process for community health workers in sub-Saharan Africa. Hum Resour Health 2019;17(1):75. [ Links ]

15. Kane S, Kok M, Ormel H, et al. Limits and opportunities to community health worker empowerment: A multi-country comparative study. Soc Sci Med 2016;164:27-34. [ Links ]

16. LeBan K, Kok M, Perry HB. Community health workers at the dawn of a new era: 9. CHWs' relationships with the health system and communities. Health Res Policy Syst 2021;19(Suppl 3):116. [ Links ]

17. Kok MC, Ormel H, Broerse JE, et al. Optimising the benefits of community health workers' unique position between communities and the health sector: A comparative analysis of factors shaping relationships in four countries. Glob Public Health 2012;12(11):1404-1432. [ Links ]

18. Oliver M, Geniets A, Winters N, Rega I, Mbae SM. What do community health workers have to say about their work, and how can this inform improved programme design? A case study with CHWs within Kenya. Glob Health Action 2015;8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4442123/ (accessed 13 October 2017). [ Links ]

19. Larson E, Geldsetzer P, Mboggo E, et al. The effect of a community health worker intervention on public satisfaction: Evidence from an unregistered outcome in a cluster-randomised controlled trial in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Hum Resour Health 2019;17(1):23. [ Links ]

20. Shakerian S, Gharanjik GS. Recruitment and selection of community health workers in Iran; a thematic analysis. BMC Public Health 2023;23:839. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15797-3 [ Links ]

21. Govender D. State of violent crime in South Africa post 1994. J Sociol Soc Anthropol 2015;06(04). http://krepublishers.com/02-Journals/JSSA/JSSA-06-0-000-15-Web/JSSA-06-0-000-15-Contents/JSSA-06-0-000-15-Contents.htm (accessed 2 April 2020). [ Links ]

22. Nelson R. Tackling violence against health-care workers. Lancet 2014;383(9926):1373-1374. [ Links ]

23. Cometto G, Ford N, Pfaffman-Zambruni J, et al. Health policy and system support to optimise community health worker programmes: An abridged WHO guideline. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6(12):e1397-e1404. [ Links ]

24. McCollum R, Gomez W, Theobald S, Taegtmeyer M. How equitable are community health worker programmes and which programme features influence equity of community health worker services: A systematic review. BMC Pub Health 2016;16(1):419. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

L S Thomas

leena.thomas@up.ac.za

Accepted 5 November 2023