Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.113 n.10 Pretoria Oct. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2023.v113i10.196

RESEARCH

Burn injuries in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa: Quantifying the healthcare burden

N AllortoI; C RenckenII; D G BishopIII

IMMed (Surg), FCS (SA); Pietermaritzburg Metropolitan Department of Surgery, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

IIScM; Brown University, Rhode Island, USA

IIIFCA (SA), PhD; Perioperative Research Group, Discipline of Anaesthesiology, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, School of Clinical Medicine, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Most burn injuries occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and affect those of lower socioeconomic status disproportionally. A multifaceted approach is needed to improve burn outcomes. Healthcare strategies and reform should be data driven, but South Africa (SA) currently lacks sufficient baseline data related to burn injuries. The absence of local data is compounded by a global lack of published data from LMIC settings. The Pietermaritzburg Burn Service Registry (PBSR) is the only established registry for burn injuries in SA

OBJECTIVES: To use the high-quality, detailed data from the PBSR to estimate the KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) provincial burden of burns in terms of length of stay, need for surgery and mortality. Our broader aim is to quantify the magnitude of the problem to highlight the need for specific burn care strategies in SA

METHODS: We conducted an observational, retrospective review of burns data from two databases, the District Health Information System (DHIS) between 2013 and 2018, and the more detailed PBSR between 2016 and 2019. We compared the distribution of mild, moderate and severe injuries as well as the distribution of adult and paediatric admissions between the DHIS and PBSR data sets. We then assumed that outcomes for the province would follow similar patterns to the Pietermaritzburg Burn Service and applied the proportions to the DHIS data set to estimate the annual provincial burden

RESULTS: In the DHIS, there was an annual mean (standard deviation (SD)) of 4 807 (760) children (age <12 years) and 3 622 (588) adults (age >12 years) admitted to hospitals in KZN with burn injuries. Annual average injury severity was 76.0% mild (mean (SD) n=5 539 (1 112.4)), 19.8% moderate (n=1 441 (148.8)) and 4.2% severe (n=312 (24.5)). These proportions were similar in the PBSR. Projections estimate that 2 967 patients would need surgery, with 212 500 hospital days required annually in the province. Additionally, provincial mortality would be 586 patients, including 84% with burns of mild and moderate severity. These deaths are potentially preventable

CONCLUSION: There is a significant, unquantified burden of burn injury in KZN, highlighting the urgent need for development of specialised surgical services for burns. Collection of more robust national data to verify our projections is required to confirm the need and guide required healthcare reform

Burn injuries are a significant contributor to global annual mortality and continue to be a leading cause of disability-adjusted life-years. It is estimated that 300 000 lives are lost each year to burns, with millions of survivors experiencing persistent negative physical and psychological sequelae.[1] It is estimated that 70% of burn injuries occur in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and affect those of lower socioeconomic status disproportionally.[2] High-income countries (HICs) have experienced a significant decrease in mortality related to burn injuries through medical advancements in the second half of the 20th century,[3] but LMICs have not seen the same results. A multifaceted approach through channels such as advocacy, policy and research is needed to improve burn outcomes in LMICs. Healthcare strategies and reform should be data driven, but South Africa (SA) currently lacks sufficient baseline data related to burn injuries.

KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) is the second most populated province in SA with ~11 million inhabitants in 2016, accounting for 19.9% of the country's population.[4] The province has no organised system of burn care. There is currently a single burns centre in a central referral hospital recognised by the provincial health department, and this is insufficient to manage the burden of burn injuries.[5] Data published from admissions at the centre describe average total body surface area (TBSA) burns of 12% in children and 18% in adults, despite over half of their admissions being from hospitals with specialist surgical services.[5] Over the past decade a burn service was established in western KZN, which offers care to ~3 million inhabitants. This service is led by a team of doctors dedicated to burn referrals and admissions within the department of general surgery. They are supported by allied health professionals such as dieticians, physiotherapists and occupational therapists. There is no specific burns unit infrastructure and patients are managed in general wards, and compete with all medical and surgical patients if intensive care is required. Part of this service is the Pietermaritzburg Burn Service Registry (PBSR), which collects demographic, injury, management and discharge data on all admitted burn-injured patients to build an electronic health record. In contrast, the District Health Information System (DHIS) for KZN collects limited data on burns, only including the severity (mild, moderate or severe) and age (child or adult) of each admission. Provincial and national data therefore lack key metrics able to quantify the burden of care and inform strategic approaches to this burden.

The absence of SA data is compounded by a global lack of published data from LMIC settings.[6] The PBSR is the only established registry in SA for burn injuries. This study sought to describe the burden of injury caused by burns in KZN. We aim to use the high-quality, detailed data from the PBSR to estimate the provincial burden of burn care in terms of length of stay, need for surgery and mortality. Our broader aim is to quantify the magnitude of the problem in order to highlight the need for specific burn care strategies and inform a provincial plan for burn injuries that could be expanded to the rest of SA.

Methods

Measures

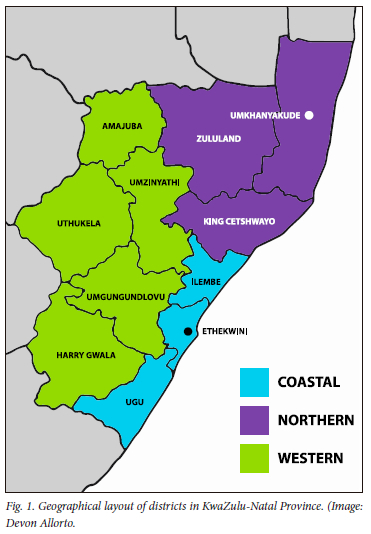

We conducted an observational, retrospective review of burns data from two databases, the DHIS and the PBSR. District-level data for prespecified parameters are routinely collected by all government hospitals. Limited data on burns are collected on the DHIS and include admission numbers of adults (>12 years) and children (<12 years) and injuries categorised as mild (<15% TBSA), moderate (15 - 30% TBSA) or severe (>30% TBSA). No data are collected on outcomes such as length of stay, need for surgery and mortality. Data are classified according to geographical area on the DHIS, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

The PBSR includes all patients admitted to the Pietermaritzburg Burn Service (PBS), including Grey's Hospital (tertiary level, admissions by referral only) and Harry Gwala Regional Hospital (formerly Edendale Hospital, admissions by walk-in or referral). Data collected include patient age, TBSA, length of stay, need for surgery and discharge outcome as alive or dead. Additional data collected include presence of inhalation injury, whether an escharotomy was performed, mechanism of the burn and location of the burn. TBSA was stratified for the PBSR as mild (<15%), moderate (15 - 30%) or severe injury (>30%), to align with the DHIS data.

Analysis

All available data from the two data sets were analysed, which resulted in data from the DHIS from 2013 to 2018, and data from the PBSR from February 2016 to January 2019. Baseline patient characteristics were reported as means (standard deviation (SD)) for continuous normally distributed variables, medians (interquartile range) for data not normally distributed, and counts (percent) for categorical variables. Comparisons between normally distributed data were done using Student's f-test, with the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test used for data not normally distributed. Categorical data were analysed using the x2 test. For all analysis a p-value <0.05 defined statistical significance, and the acceptable power was 80%.

We compared the distribution of patients between the mild, moderate and severe injury categories as well as the distribution of adult and paediatric admissions between the DHIS and PBSR data sets. We then assumed that outcomes for the province would follow similar patterns to the PBS and applied the proportions of both outcomes (mortality, need for surgery and length of stay) and transfer criteria published from the South African Burn Society (age <1 year or >60 years, special area burns, inhalation injury, need for escharotomy, electrical or chemical burns, and concomitant trauma) to the DHIS data set to estimate the annual burden in numbers. We used the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement guidelines to report our study. [7] The complete STROBE checklist is available online as Appendix 1 (https://www.samedical.org/file/2086).

Ethical approval

Approval for the data collection for the DHIS was granted by the Biomedical Research and Ethics Committee, University of KwaZulu-Natal (ref. no. BCA056/13). The PBSR has class approval granted by the Biomedical Research and Ethics Committee, University of KwaZulu-Natal (ref. no. BCA106/14).

Results

Seventy-six hospitals report total admissions data to the DHIS. Thirty-five were excluded from the study, 26 because they do not admit burn patients and 9 owing to missing data for patient age (child v. adult) and burn severity. Of the 41 included in the analysis, 27 (65.9%) were district hospitals, 10 (24.4%) were regional hospitals, 3 (7.3%) were tertiary hospitals, and 1 was a central hospital. Details of the provincial health structure are described in Appendix 2 (https://www.samedical.org/file/2087). In the DHIS, there was an annual mean (SD) of 4 807 (760) children (age <12 years) and 3 622 (588) adults (age >12 years) admitted with burn injuries to hospitals in KZN between 2013 and 2018 (Table 1). Comparing admission numbers of children and adults between the DHIS and PBSR injury categories showed no significant difference, with children comprising 57.0% and 55.2% of the cohorts, respectively. Most injuries were <15% TBSA at 76.0% and 72.7%, respectively (p=0.97; p=0.99) (Table 1).

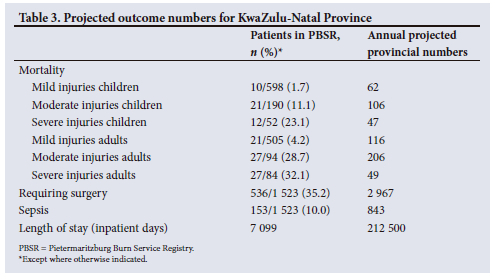

The PBS data illustrate that children tended to sustain injuries <30% TBSA compared with a much larger proportion of severe injuries (>30%) in adults (Table 2). Mortality increased with worsening severity and was higher in the adult group compared with the paediatric group in all three severity categories. In the minor injury group, 35.0% of paediatric patients and 40.2% of adults required surgery, with lower percentages receiving surgery in the severe group. The mean (IQR) length of stay for injuries <15% TBSA was 11 (13) days, for injuries 15 - 30% TBSA 23 (25) days, and for injuries >30% TBSA 10 (24) days. The lower mean length of stay and surgical rates in the severe injury group are due to the higher mortality rate and early deaths in this group. Projected outcome numbers for KZN are presented in Table 3. The annual predicted numbers of patients for the province meeting the criteria for transfer to a burns unit are presented in Supplementary Table 1 (Appendix 3, https://www.samedical.org/file/2088), together with the South African Burn Society criteria for transfer to a burns centre (Supplementary Table 2, Appendix 3).

Discussion

Our study confirmed that annual burn injuries place a significant unmeasured burden on the provincial healthcare system. Burn injury is a complex condition, and an organised system of acute, chronic and rehabilitative care should be provided for patients with burn injuries.[8] Organised burns centres equipped to meet the unique needs of burn patients can improve survival rates and outcomes for survivors.[9] The multidisciplinary needs of burn patients call for a range of experts[10] including surgeons, anaesthesiologists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, dieticians, psychologists and nurses, and highlight the requirement for organised and dedicated burns units with centralised care. Currently there is only one burns centre in KZN. The lack of dedicated regional or tertiary burns units and the lack of a strategic approach to burn management is a major deficit that needs to be addressed.

Previous research looking at workforce resources for burns in SA showed that only 37% of doctors managing burn patients had a specialist qualification and that the majority were only involved in burns on a part-time basis. [9] Only two-thirds had received some form of postgraduate training in management of burns. Difficult working environments and lack of training and skills development were cited as major deterrents to working in burns.[11] Currently, the province and the country are unable to cope with the burden of burn injury, and early surgical access is unlikely to be possible in this context. KZN has ~8 500 burn injuries requiring admission to hospital annually, suggesting that ~2 967 patients would require surgery across the province, 843 patients would require treatment for sepsis, and 212 500 hospital days would be required.

Analysis of the PBSR data set shows a significant number of injuries meeting the criteria for transfer to a burns centre (Supplementary Table 1, Appendix 3). This translates into huge numbers requiring care in a burns unit and suggests potential revisitation of the traditional criteria for transfer to a burns centre[12] as published in 2007 by the South African Burn Society (Supplementary Table 2, Appendix 3). Authors from Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital in Cape Town, an established burns centre, describe the use of WhatsApp as a communication tool for paediatric burn care between the burns centre and their referral hospitals.[13] They were able to avoid 160 admissions over an 18-month period despite those patients meeting the criteria for transfer. The Vula Medical Referral app is a free, locally developed app that represents a successful alternative to traditional referral methods. A tertiary orthopaedic service in Western Cape Province managed one-third of referrals with advice only, therefore avoiding unnecessary transfer and relieving an overburdened service.[14] With an effective outreach system in place, many injuries that meet the transfer criteria can be successfully managed at district level, in conjunction with remote specialist advice. An effective outreach system would allow regional and tertiary centres to focus on larger and more complex burn injuries.

Reducing child mortality is an important global goal in the health sector. Sustainable Development Goal 3 calls for an end to preventable deaths of newborns and children aged <5 years.[15] In 2015, non-natural deaths accounted for 7.9% of deaths of children under 5 years. Mortuary data from Mpumalanga Province reported the fatal burn rate to be 3.8 per 100 000 inhabitants,[16] with data from Western Cape Province showing more than doubling of the death rate over a 20-year period.[17] In Cape Town, burn mortality in children was reported as 3.6% and that in adults 7.9%.[18]

As an international comparison, an audit of mortality from the Global Burn Registry, a World Health Organization initiative, showed overall mortality to be 17% in LMICs v. 9% in HICs.[19] In our data set, patients with mild injuries had a mortality rate of 1.7% for children and 4.2% for adults, while mortality in the moderate injury group was 11.1% for children and 28.7% for adults. These figures are remarkably high for a dedicated burn service, and potentially translate to 62 children with minor injuries and 106 children with moderate injuries dying annually in KZN from survivable burns. Reducing preventable mortality from burn injuries in this patient category needs to be prioritised.

A national and provincial strategy for burn care urgently needs to be developed. Revision of the transfer criteria needs to be undertaken to appropriately triage the burden of injury for our setting. Revision of the transfer criteria needs to be coupled with skills development in the existing regional and tertiary hospitals so that undue burden does not fall on the single centre in the province. The Department of Health would need to invest in training as well as improved resource allocation. The development of the PBS has demonstrated that a significant proportion of the burden can be managed at a regional level with dedicated burn care. Previous publications from the PBS have shown that while there was an improvement in care with the development of a dedicated service, mortality is still not acceptable and requires some investment by the health department towards improved infrastructure and resource allocation.[20,21] Finally, improved data collection is essential to accurately quantify the magnitude of the burden, and to assess the impact of interventions that take place.

Healthcare reform is often driven by increased awareness of the extent and impact of disease on society, for which this article lays a foundation. The DHIS should incorporate an increased number of burn-specific fields that will be used to determine the deficits in care. These data can be used to develop and drive quality improvement initiatives for reducing preventable mortality. Regional and central burn services should adopt systems similar to the PBSR for more detailed data on surgical management and outcomes, with similar quality improvement initiatives introduced at that level.

Prevention of burns is a key element to healthcare and should be included in national strategies. Literature reviews on burn prevention in LMICs show that education of targeted groups such as school-aged children or families can be effective in reducing hazardous behaviours, but has no demonstrable effect on incidence, morbidity or mortality.[22] Further studies with adequate outcomes data on burn prevention initiatives in LMICs are needed. Effective solutions are multipronged and include technology and legislation as well as educational initiatives, which remain challenging in LMICs.[22,23]

Study strengths and limitations

The major limitation of this article is the lack of robust provincial and national data through the DHIS. Insufficient key parameters are available, and data between numbers of admissions and severity of burns do not correlate well. In order to mitigate against incomplete data entry, we assumed that the admissions rate was correct and applied the DHIS severity of injury proportions to these data. While the data from the PBS are more robust, they may not be representative of the provincial case mix or the outcomes, given that it is a dedicated burns team that runs the service.

Future research

Understanding the current level of knowledge and skill as well as resources currently available for burn care in regional hospitals in KZN would be useful in order to target intervention. Collecting burn outcomes in the rest of the province is essential, so that the impact of interventions can be measured. Provincial and national data systems need to be strengthened to include key parameters such as length of stay, surgical requirement and mortality.

Conclusion

There is a significant, poorly quantified burden of burn injury in KZN, highlighting the urgent need for development of specialised surgical services for burns as well as burn prevention strategies. The former includes the development of burns units at a regional and tertiary level to provide surgery and a system to prioritise timing of surgery in a context-sensitive manner. Appropriate infrastructure and resource allocation is paramount. Training, education and outreach support should be an integral component in the functioning of the specialised burn care centres. Access to expertise through the application of modern technology to avoid unnecessary transfer, and revision of transfer criteria to maximise efficiency in an overburdened system, are other strategies to be considered. Collection of more robust data to confirm our projections is required in order to confirm the need and guide the healthcare reform that is required.

Declaration. The research for this study was done in partial fulfilment of the requirements for NA's PhD degree at the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Acknowledgements. None.

Author contributions. All authors were involved in the conceptualisation of the study and the development and write up of the article, and approved the final version.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. World Health Organization. A WHO plan for burn prevention and care. Geneva: WHO, 2008. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/97852 (accessed May 2022). [ Links ]

2. Stokes MAR, Johnson WD. Burns in the Third World: An unmet need. Ann Burns Fire Disasters 2017;30(4):243-246. [ Links ]

3. Tompkins RG. Survival from burns in the new millennium: 70 years' experience from a single institution. Ann Surg 2015;261(2):263-268. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000000623 [ Links ]

4. Statistics South Africa. Home page, population 2016. https://www.statssa.gov.za/ (accessed 31 August 2020). [ Links ]

5. Den Hollander D, Albert M, Strand A, Hardcastle TC. Epidemiology and referral patterns of burns admitted to the Burns Centre at Inkosi Albert Luthuli Central Hospital, Durban. Burns 2014;40(6):1201-1208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2013.12.018 [ Links ]

6. Wesson HKH, Bachani AM, Mtambeka P, et al. Pediatric burn injuries in South Africa: A 15-year analysis of hospital data. Injury 2013;44(11):1477-1482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2012.12.017 [ Links ]

7. Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2007;147(8):W-163-W-194. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010-w1 [ Links ]

8. ISBI Practice Guidelines Committee. ISBI practice guidelines for burn care. Burns 2016;42(5):953-1021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2016.05.013 [ Links ]

9. Al-Mousawi AM, Mecott-Rivera GA, Jeschke MG, Herndon DN. Burn teams and burn centers: The importance of a comprehensive team approach to burn care. Clin Plast Surg 2009;36(4):547-554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cps.2009.05.015 [ Links ]

10. Herndon DN, Blakeney PE. Chapter 2 - Teamwork for total burn care: Achievements, directions, and hopes. In: Herndon DN, ed. Total Burn Care. 3rd ed. Elsevier, 2007:9-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-1-4160-3274-8.50005-2 [ Links ]

11. Allorto NL, Zoepke S, Clarke DL, Rode H. Burn surgeons in South Africa: A rare species. S Afr Med J 2016;106(2):186-188. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i2.9954 [ Links ]

12. Karpelowsky JS, Wallis L, Madaree A, Rode H; South African Burn Society. South African Burn Society burn stabilisation protocol. S Afr Med J 2007;97(8):574-577. [ Links ]

13. Martinez R, Rogers AD, Numanoglu A, Rode H. The value of WhatsApp communication in paediatric burn care. Burns 2018;44(4):947-955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2017.11.005 [ Links ]

14. Morkel RW, Mann TN, du Preez G, du Toit J. Orthopaedic referrals using a smartphone app: Uptake, response times and outcome. S Afr Med J 2019;109(11):859-864. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2019.v109i11.13986 [ Links ]

15. Bamford LJ, McKerrow NH, Barron P, Aung Y. Child mortality in South Africa: Fewer deaths, but better data are needed. S Afr Med J 2018;108(3a):s25-s32. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2018.v108i3.12779 [ Links ]

16. Blom L, van Niekerk A, Laflamme L. Epidemiology of fatal burns in rural South Africa: A mortuary register-based study from Mpumalanga Province. Burns 2011;37(8):1394-1402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2011.07.014 [ Links ]

17. Cloake T, Haigh T, Cheshire J, Walker D. The impact of patient demographics and comorbidities upon burns admitted to Tygerberg Hospital Burns Unit, Western Cape, South Africa. Burns 2017;43(2):411-416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2016.08.031 [ Links ]

18. Van Niekerk A, Laubscher R, Laflamme L. Demographic and circumstantial accounts of burn mortality in Cape Town, South Africa, 2001 - 2004: An observational register based study. BMC Public Health 2009;9:374. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-374 [ Links ]

19. Jacobs C, Vacek J, Many B, Bouchard M, Abdullah F. An analysis of factors associated with burn injury outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. J Surg Res 2021;257:442-448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2020.08.019 [ Links ]

20. Allorto NL, Clarke DL. Merits and challenges in the development of a dedicated burn service at a regional hospital in South Africa. Burns 2015;41(3):454-461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2014.07.021 [ Links ]

21. Smith MTD, Allorto NL, Clarke DL. Modified first world mortality scores can be used in a regional South African burn service with resource limitations. Burns 2016;42(6):1340-1344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2016.03.024 [ Links ]

22. Parbhoo A, Louw QA, Grimmer-Somers K. Burn prevention programs for children in developing countries require urgent attention: A targeted literature review. Burns 2010;36(2):164-175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2009.06.215 [ Links ]

23. Rybarczyk MM, Schafer JM, Elm CM, et al. Prevention of burn injuries in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Burns 2016;42(6):1183-1192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2016.04.014 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

N Allorto

nikkiallorto@gmail.com

Accepted 20 July 2023