Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.113 no.7 Pretoria jul. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2023.v113i7.1104

EDITORIALS

Developing a pipeline of African global surgery scholars

Global surgery is developing as a new discipline in many countries. Global surgery primarily aims to improve access to quality surgery in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Therefore, ensuring appropriate LMIC representation and leadership in global surgery research, projects and innovations is essential. There is a paucity of pathways for students and young clinicians in LMICs to attain training in and exposure to global surgery research and projects. If equity in global surgery leadership and scholarship is truly desired, steps need to be taken to ensure that more students and young clinicians in LMICs are exposed to global surgery as an academic discipline and are offered pathways to practice and leadership. This editorial explores ways of ensuring these steps through increased exposure, increased training and increased funding.

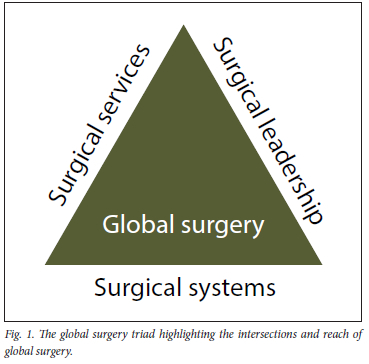

Global surgery is defined as an area of study, research, practice and advocacy that seeks to improve health outcomes and achieve health equity for all people who need surgical, obstetric and anaesthesia care, with a special emphasis on underserved populations and populations in crisis. Global surgery primarily aims to improve access to quality surgery in LMICs.[1] Global surgery is developing as a new discipline in many countries. In practice, global surgery varies from interventions that enable the provision of safe and timely essential surgical services to strengthening surgical health systems, especially in district hospitals, to improving access to surgical services through policy and population-wide programmes. With this aim in mind, it is safe to say that investment in the development of global surgery as a discipline can ultimately increase the impact of all surgical disciplines (Fig. 1).

Ensuring appropriate LMIC representation and leadership in global surgery research, projects and innovations is essential, as by its very definition global surgery is particularly relevant to LMICs. There are currently more global surgery educational programmes in high-income countries (HICs), and the representation in international global surgery programmes is skewed in favour of HICs. The paucity of pathways for students and young clinicians in LMICs to attain training in and exposure to global surgery research and projects might be one of the reasons for this skewed respresentation.

Creating a pipeline for African global surgery scholars will promote longevity in the field, and will enable the harnessing of the energy, ideas and cultural competencies contextually relevant to LMICs. The introduction of formalised global surgery programmes will better equip students for work in the discipline of global surgery, and could also increase the credibility of the discipline.[2] To enhance equity in global surgery leadership and scholarship, more students and young clinicians in LMICs should be exposed to global surgery as an academic discipline, and provided with pathways to practice and leadership.

In recent years, there has been an increase in interest in the field of global health, of which global surgery is an essential component'.[2] This increased interest, coupled with the understanding of the fields importance, has resulted in increased academic opportunities such as formalised academic programmes, electives and postgraduate fellowships in global surgery. Over the years, more opportunities for training and exposure to global surgery have emerged, including fellowships through non-governmental organisations (NGOs) such as Operation Smile and the African Paediatric Fellowship Programme, and the increasingly ubiquitous student organisation InciSioN (International Student Surgical Network). However, when one considers programmes housed in academic institutions, most of these are found in HICs, such as the USA and UK. There is a disproportionately higher number of global surgery academic programmes and opportunities to study in HICs. We found a non-exhaustive list of 12 institutions that provide training, research, experience or funding for training in global surgery in the USA alone.[2] Taking a comparative look at the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region, which includes 16 of the 54 internationally recognised countries within the African continent, we find that cumulatively, these countries have only five centres of global surgery, with two of these centres offering or in the process of offering formalised programmes such as fellowships, Masters and PhDs in global surgery. Many US fellowships allow, and even encourage, applicants from LMICs. However, these programmes are unfunded or partially funded, making them prohibitively expensive for most applicants from LMICs. A recent international survey done by the InciSioN Collaborative noted that 43% of participants named the lack of an established career paths as a barrier to pursuing a career in global surgery.[3] In addition, almost 40% of participants named financial constraints as a barrier. Therefore, it is not enough to motivate for more LMIC applicants to be accepted into these international programmes - more home-grown solutions are needed, alongside an African pipeline for African global surgery leaders. Home-grown solutions mitigate against costs such as visas and living expenses in HICs, and most importantly, ensure that global surgery training is contextual and relevant to LMICs. This African pipeline must take the form of three tracks: increased exposure, increased training and increased funding.

Increased exposure

While the principles of global surgery - equity, access and safety -have been studied and implemented in Africa tor years, the unifying field of global surgery is still gaining traction. To address the growing interest in this field we must expose African medical students and junior doctors to global surgery, by embedding global surgery into the medical school curriculum and hosting conferences and workshops in African countries, making them more accessible to these future global surgery leaders. A rigorous alternative would involve funding African global surgery thinkers and leaders to design and host their own global surgery networks and conferences. An example of this is the AfroSurg Collaborative created in 2020,[4] which seeks to set a global surgery agenda for the SADC region. AfroSurg allowed medical students and junior doctors to participate in research and research agenda-setting, and exposed them to possible global surgery mentors. This opportunity would not be as accessible if the same conference was held in a HIC.

Increased training

Ultimately, increases in funding and exposure will lead to both a demand for and the platform to increase global surgery training in Africa. To create credible and competent global surgery leaders in Africa, it is imperative that training in global surgery encompasses formalised exposure to, and involvement in, global surgery research and projects. For this to occur, tertiary institutions in Africa must begin to form and expand global surgery entites and to house degree and non-degree programmes. These programmes can take on many formats, from mentored research assistantships, fellowships, Master's programmes and electives. Without the qualifications and acknowledgements of formalised programmes and curriculums, it is difficult for young clinicians and students to quantify their global surgery qualifications and experience. Formalised programmes also increase the access to mentorship, which is broadly acknowledged as a critical component of a successful career.

Increased funding

While strides have been taken to ensure that applicants from LMICs can access funding for some large international grants, the grants are often administered through institutions in HICs. For sustainable and long-term change to occur, more investment is needed in African institutions. An example of this is the MEPΙ (Medical Education Partnership Initiative) grant in Zimbabwe,[5] which resulted in short-term and long-term improvements to infrastructure, human resources and research capabilities, which all provide a platform for future academics and clinicians to build on and grow in. The MEPΙ grant included examples of the development of structured programmes[5] in Africa for African clinicians and students - all taking place in a student's home country, minimising the programme cost and ultimately ensuring that available funding generates more utility. This is particularly important for students and junior clinicians, who often do not have much disposable income. Similarly to the funding of the AfroSurg conference, more funding should be earmarked for African-focused and hosted conferences, allowing Africans to set their own agenda and design contextually driven and appropriate solutions. It is also vital that research funding in Africa is broadened to include funding for local global surgery research-related projects. Going even further, there is a need for more local and national government as well as private and NGO investment in global surgery holistically, including global surgery training. African governments and institutions should be investing in global surgery. For this to become reality, increased advocacy within tertiary institutions and governmental departments is necessary to explain the importance and benefit of increased global surgery funding for the health of a population.

Furthermore, it is important to find easy pathways for students and trainees to access global surgery training such as intercalated programmes. This would allow students and trainees the opportunity to seamlessly spend a year in a global surgery training programme in the middle of their degree, and return to the degree programme.

It is also essential to increase awareness of the fact that training in global surgery is training in health systems, training in advocacy and training in transdisciplinary approaches to solving health problems, hence enhancing medical and health sciences training in general.

Conclusion

To ensure adequate representation of LMICs in global surgery investment needs to be made of time, effort and money in the creation of clear pathways for training opportunities and funding in global surgery projects and research. While these pathways are wholly lacking in LMICs, a focus on creating these pathways for young aspiring African global surgery leaders, even starting with workshops in undergraduate classrooms, could not only increase surgical access for all, but could in the long term provide longevity, rigorous diversity and new energy to the global surgery mandate on the continent.

P Francis

Global Surgery Division, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa frnpea001@myuct.ac.za

KChu

Centre for Global Surgery, Department of Global Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town South Africa

M Isiagi

Global Surgery Division, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

G Fieggen

Department of Surgery, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

C Gordon

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Health Sciences., University of Cape Town, South Africa

S Maswime

Global Surgery Division, Department of Surgery, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Funding. SM is funded through a South African Medical Research Council Midcareer scientist award.

References

1. Meara JG, Leather AJM, Hagander L, et al. Global surgery 2030. Evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet 2015;386(9993):569-624. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X [ Links ]

2. Krishnaswami S, Stephens CQ, Yang GP, et al. An academic career in global surgery. A position paper from the Society of University Surgeons Committee on Academic Global Surgery Surgery 2018;163(4):954-960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2017.10.019 [ Links ]

3. Incision Collaborative. International survey of medical students exposure to relevant global surgery (ISOMERS). A cross-sectional study World J Surg 2022;46(7):1577-1584. http://doi.org/10.1007/S00268-022-06440-0 [ Links ]

4. Breedt DS, Ödland ML, Bakanisi B, et al. Identifying knowledge needed to improve surgical care in Southern Africa using a theory of change approach. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6(6):e005629. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005629 [ Links ]

5. Hakim JG, Chidzonga MM, Borok MZ, et al. Medical education partnership initiative (MEPΙ) in Zimbabwe. Outcomes and challenges. Glob Health Sci Pract 2018;6(1):82-92. https://doi.org/10.9745/GHSP-D-17-00052 [ Links ]