Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.113 n.6 Pretoria Jun. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2023.v113i6.16679

RESEARCH

Patients' experiences of termination of pregnancy at a regional hospital in Durban, South Africa

V MbonaI; GKistanII, III; H M SebitloaneIV

IMB ChB; Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Nelson R Mandela School of Medicine, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IIFCOG (SA), MMed(O&G); Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Nelson R Mandela School of Medicine, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IIIFCOG (SA), MMed(O&G); Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Addington Hospital, Durban, South Africa

IVMMed (O&G), PhD; Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Nelson R Mandela School of Medicine, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Safe and effective termination of pregnancy (ToP) services have helped to resolve the uncertainty that surrounds unwanted pregnancies globally and in South Africa (SA). It is important to determine the demographic profile of women requesting ToP and to assess the reasons for ToP and the beliefs and experiences of women seeking these services in order to improve service delivery

OBJECTIVES: To determine the sociodemographic profile and emotional and psychological experiences of women undergoing ToP at a regional hospital in Durban, SA

METHODS: The study population consisted of women seeking either medical or surgical ToP at the Addington Hospital ToP clinic from June to August 2021. The participants were requested to complete a structured self-reporting questionnaire on their sociodemographics, their awareness of, attitude to and knowledge of ToP, and their reasons for seeking ToP services, as well as contraception method and use. The questionnaire also captured their experience after the ToP was completed

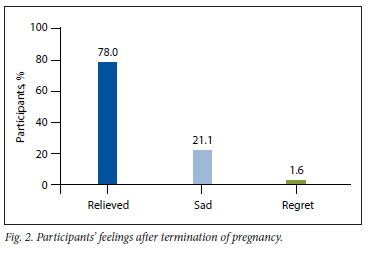

RESULTS: Of the 246 participants, the majority (92.3%) were aged 16 - 35 years, with 62.6% having little or no income and dependent on their family or partner for financial support. Most of the participants (73.2%) were parous and had secondary education and above (94.3%). Furthermore, 59.0% of the participants indicated they were not on any form of contraception before becoming pregnant, even though 70.3% of them were single. The most cited reasons for ToP were lack of finance (37.5%), schooling (33.9%), and not feeling ready to be a parent (20.0%). Although some participants (35.7%) were fearful of ToP, most of them (78.0%) reported feeling relieved after the procedure

CONCLUSION: Unemployment and financial dependency appeared to be common reasons for seeking ToP in our study population. Most of the women were single and many had not used any contraception prior to the pregnancy

Globally, up to 41% of pregnancies are unintended.[1] Increased contraceptive use has reduced the number of unintended pregnancies, but has not eliminated the need for safe abortion. In addition, -33 million contraceptive users globally experience accidental pregnancy annually[1] Since 1996, South Africa (SA) has legalised termination of pregnancy (ToP) through the Choice of Termination of Pregnancy Act 92 of 1996.[2] This Act allows for safe, effective and accessible ToP, allows first-trimester TOP on request, and further stipulates that ToP may only be performed at accredited facilities designated by the province.[2] Since the inception of the Act, up to 7% of pregnant women have sought legal ToP in SA.[3] First-trimester terminations are performed as outpatient procedures by trained midwives. Adequate counselling is given, and women are offered the choice of medical or surgical ToP.[2]

International data suggest that women decide to have ToP because of a desire to stop or postpone childbearing[3] Local data indicate that women in the SA setting often have numerous reasons for ToP, such as financial difficulties, formal education not completed, contraceptive failure, wrong timing, and reasons relating to the family or partner.[3] A study in Hammanskraal found that women presenting for ToP were likely to be young, unemployed, poorly educated, in a conflictual relationship with their partner, and dependent on their parents.[4] The reasons for ToP were relationship or financial problems, need for completion of studies, or not being ready to become a parent. Many women seeking ToP, particularly repeat ToP, experienced negative attitudes from health professionals. Women presenting for ToP, some of them vulnerable adolescents, had often not been on contraception before becoming pregnant, for reasons that were complex or not clearly understood, e.g. lack of knowledge of contraception, poor access to services, lack of motivation to seek contraceptive services, and fear of stigma or judgement by healthcare professionals.

There remains a paucity of data on women's experiences after ToP In a local study in Johannesburg, women experienced both physical and emotional discomfort (uncertainty and confusion) following ToP, while some women suffered religious dilemmas and others reported relief after the procedure.[5] The most consistent findings after ToP were changed relationships with partners, family and friends, and a need for isolation. Studies on women undergoing ToP are very useful in informing health policies, as they may identify groups that require intensive counselling on specific findings, such as failure to use contraception or inconsistent use thereof. In our study we therefore hoped to identify women who seek ToP, reasons for choosing to have the procedure, and women's experiences at our facility, with the aim of establishing interventions to target populations at risk and improve contraceptive use in these individuals/groups. Furthermore, we aimed to assess experiences after ToP in order to counsel these women adequately and support them in returning to their lives and society.

Methods

Study design and location

This was a descriptive, cross-sectional study conducted at Addington Hospital, a regional hospital in Durban, SA. After receiving counselling and information on the study, women signed informed consent and voluntarily completed the pre- and post-procedure questionnaire. Addington Hospital is the only licensed public institution offering ToP services to women living in the Durban Central and South Beach areas. The ToP clinic operates 5 days a week (from Monday to Friday).

Study population

The study population consisted of women in their first trimester of pregnancy seeking medical or surgical ToP at the Addington Hospital ToP clinic. Convenience consecutive sampling was adopted.

Inclusion criteria

Women aged >16 years, presenting for termination of pregnancy at the ToP clinic, and who were <12 weeks pregnant, of sound mental state and able to give consent to participate in the study, were included. All the recruited women met the eligibility criteria for ToP according to the Termination of Pregnancy Amendment Act (38 of 2004).[6]

Exclusion criteria

Women who were more than 12 weeks pregnant and those who declined to take part in the study were excluded.

Sample size

The sample size required for the study to be well powered was 241 participants. A total of 246 participants were recruited into the study.

Data collection tool

The participants were requested to complete a self-report and standardised structured questionnaire on ToP. The questionnaire comprised a total of 23 items, 12 on the sociodemographics of the participants, and 11 on their awareness of, attitude to and knowledge of ToP, and their reasons for seeking ToP services. Most of the questionnaire items were single questions self-reporting on the participants' demographic or personal characteristics. Their attitudes to and practices regarding contraception, including the method of contraception, were also explored. In the second part of the questionnaire, completed after the ToP, patients' feelings about the procedure and their experiences were explored. The questionnaire was translated into isiZulu, the local language. Translation of the questionnaire back into English was performed by an independent translator to verify the translation. Patients were given a description of the study at their first appointment at the ToP clinic and were asked to consider participating. They were assured that their identity and responses would remain confidential and anonymous and that their decision to participate would not affect their care in any way The questionnaire was completed in a private setting at the ToP clinic before the patients received counselling or other interventions, and at follow-up 2 weeks after medical ToP, and after the procedure for those who had surgical TOP. The study was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (ref. no. BREC/00001082/2020).

Data analysis

Statistical analysis of the data obtained was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 25 (IBM, USA). Means with standard deviations were used to express continuous variables. A p-value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Owing to the nature of the study, both categorical and numerical variables were used when analysing all collected data. Simple descriptive statistical methods were used.

Results

Demographics

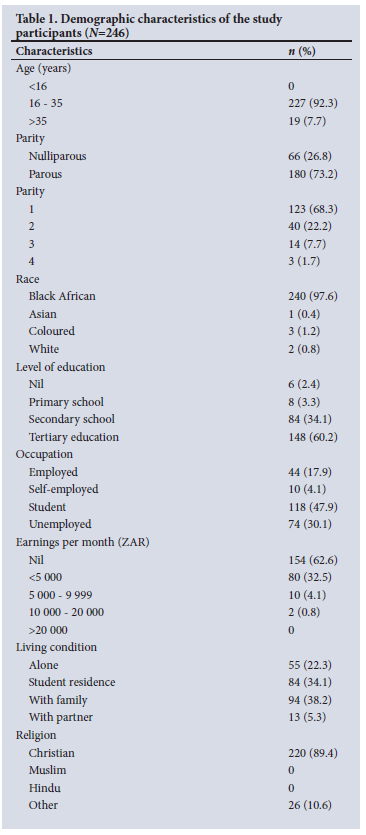

Table 1 shows the demographic profile of the 246 study participants. Most (75.6%) of the participants reported being HIV negative, 23.2% were HIV positive, and 1.2% were unaware of their HIV status or declined testing. The majority of the participants (96.7%) were seeking ToP for the first time. Most participants (70.3%) were single. With regard to contraceptive use, 41.0% used contraception, with most users on injectable contraception (20.3% of total participants), and the remaining women on the oral contraceptive pill, an implant or the intrauterine contraceptive device. Only 8 participants (3.2% of the total) used barrier contraception (condoms). Fifty-nine percent of the participants had used no method of contraception before becoming pregnant.

Most (56.9%) of the participants stated that they had obtained information about ToP through word of mouth, 35.3% reported getting information from social media, while 7.8% reported getting information from the news or from television.

Of the participants, 31.3% did not tell anyone that they were seeking ToP, 27.6% told their partner, 12.6% told their family 27.2% told a friend or colleague, and 1.2% told both their partner and their family. Of the 169 participants who told someone that they were seeking ToP, 11.2% reported that the person they told was unsupportive, 65.7% that the person was supportive, 17.8% that the person encouraged ToP, 3.6% that the person encouraged them to continue the pregnancy, and 1.8% that the person gave no response. When asked what ToP procedure they had undergone, 87.8% stated that they had had a medical procedure and 12.2% that they had had manual vacuum aspiration. When asked what post-ToP contraception they had adopted or planned to use, 5.7% of participants intended to use condoms, 38.2% injectable contraception, 24.8% an implant, 10.2% an intrauterine device and 4.1% combined oral contraception; 2.8% intended to use more than one contraceptive, 13.4% were still deciding, and 0.8% intended to have tubal ligation.

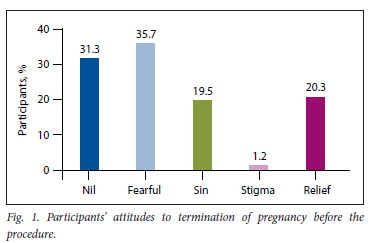

Fig. 1 shows the participants' responses to the question regarding their attitude to ToP before the procedure. Twenty participants (8.1%) cited more than one attitude to ToP, both being fearful and feeling that ToP was a sin.

Participants' responses to the question regarding their reason for ToP were varied. The most cited reason was lack of finance (37.5%), followed by schooling (33.9%), not feeling ready to be a parent (20.0%), partner problems (11.7%), family pressure (9.3%), contraceptive failure (6.9%), fear (6.5%), wishing to limit childbearing (4.0%), rape (2.0%) and break-up with a partner (2.0%), while domestic violence (1.2%) was the least cited reason. Many participants (35%) cited more than one reason for ToP, most commonly lack of finance and/or schooling combined with not being ready to be a parent.

Fig. 2 shows participants' feelings after ToP. Of the participants, 78.0% reported being relieved, 21.1% feeling sad, and 1.6% experiencing regret. Two participants expressed combined feelings of sadness and regret.

Participants were requested to rate the ToP service on a scale of 1 to 10. The majority (81.3%) gave a rating of 10/10 for the service and care they received, 6.9% gave a rating of 5, 5.3% gave a rating of 8, 3.7% gave a rating of 7, 2.0% gave a rating of 9, and 0.8% gave a rating of 6. Participants were asked to comment on how to improve the ToP services received. Of the participants, 84.1% did not answer the question, 8.5% indicated that they were either satisfied with the service or felt there was no need for improvement, and 7.3% made suggestions for service improvement (more trained nurses/ ToP service providers needed and quicker/more effective service delivery).

Discussion

Our study showed that the majority (92.3%) of the women seeking ToP were aged 16-35 years, and that a high proportion of them (62.6%) had little or no income and were dependent on their family for financial support. These findings are consistent with previous studies on women requesting ToP in SA, which have reported similar demographic characteristics, namely that many of them are young, unemployed, and dependent on their parents.[4,7] In our study, the majority of the participants (94.3%) had at least secondary education, in contrast to the findings of a previous study that found most of the women seeking ToP to be poorly educated.[4] We found that most of the participants in our study had poor financial support, which may be a major factor encouraging women to seek ToP services and is similar to findings in previous studies.[4,7-9]

Of the participants in the present study, 59.0% had not used any form of contraception before becoming pregnant, which indicates that poor use of contraception is a major issue that needs to be addressed to improve women's health. This finding highlights the need for proper education on contraceptive use, which will reduce the strain on ToP clinics. Designing programmes that will help improve knowledge on the use of contraceptives will help eliminate high-risk behaviours and the need to seek ToP.[10] Research shows that limited knowledge about sexual and reproductive health is a key factor responsible for low use of contraception as well as safe abortion services. It is important to urgently address the unmet need for contraception and improve access to contraception and information about ToP services.[11]

The importance of proper education of women regarding availability of ToP services cannot be overemphasised. The findings of the present study illustrate this need, as most of the participants (56.9%) had heard about the availability of ToP services through word of mouth. It is necessary to make use of mass media, healthcare workers and healthcare facilities for dissemination of information regarding ToP services. A study by Munakampe et al.[11] showed that although healthcare workers are essential and reliable sources of information, most information regarding ToP and contraception is not passed through them. Education of women about ToP by skilled individuals such as medical educators is essential because of the technical skills involved.

A significant proportion of the participants in the present study (68.7%) told a second party about their decision to seek ToP services.

However, although 83.5% of them reported that the person they told was supportive and/or encouraged ToP, 11.2% found that the person was unsupportive. Family pressures and partner problems have been reported in other studies to be major reasons for seeking ToP [8,11,12] studies have shown that the decision to request ToP is often controlled by family members or partners, putting great pressure on women seeking these services.[8,11,12] In addition, social condemnation of ToP can drive women to attend practitioners of illegal TOP done in secrecy.[13]

Our study shows that after seeking ToP, most participants adopted a means of contraception, with only 13.4% reporting that they were still deciding which method to use. The increase in the number of participants who adopted contraceptive measures immediately after ToP compared with the number using contraception before they fell pregnant is encouraging, as contraception reduces the chance of pregnancy and pregnancy-related morbidity and mortality. Postabortion contraceptive counselling is incorporated into and serves as an integral part of ToP services.[14]

Our study found that most (78.0%) of the participants reported feeling relieved after their ToP procedure. This feeling of relief may be associated with the fact that the responsibility of taking care of a newborn and the associated financial implications are lifted, as the reasons for ToP most cited by participants in the current study were lack of finance (37.5%) and the need to complete their formal education (33.9%). The relief may also be due to feeling that they were not ready to become a parent, as stated by some participants (20.0%) in our study. A study by Roca et al.[15] has shown that women experience various emotions after abortion; however, 5 years after the procedure, relief was the most commonly experienced emotion. Research indicates that abortion-related emotions are associated with personal and social contexts, rather than being a product of the abortion procedure itself.[15] Healthcare professionals' policies and rationale for administering ToP should therefore not be based on the premise of emotional harm.[16]

All the participants in the present study rated the ToP service above average, and only a few made suggestions for ways improve the service, such as employing more staff and that same-day procedures would be preferred. These obstacles are due to financial constraints and staff shortages, and this feedback will be addressed by the hospital management.

This cross-sectional study described a sufficient number of women for us to draw conclusions. One weakness was selection bias, as only women who agreed to answer the questionnaire were included in the study population. Responder bias may also have been encountered, as some of the questions in the study were of a personal nature, so some participants may not have felt free to answer honestly for fear of being judged. There is also a possibility that recall bias may have been experienced.

Conclusion

Most of the women seeking ToP in this study were single, and despite a relatively good overall level of education, the majority were not using any form of contraception, despite residing in the inner city where there are health facilities within easy reach. However, it was remarkable that the majority were not repeat users of ToP, giving some hope that most will adhere to the contraceptive method chosen after ToP.

Recommendation

ToP services should be integrated into both public and private healthcare centres to increase accessibility and on-demand service.

The public should be properly educated about use of family planning options in order to avoid unnecessary ToP.

Future research on ToP services is crucial to better understand patient experiences and service delivery. The majority of ToP seekers in our study were not on contraception, highlighting the need for further research exploring the reasons for non-use of contraception in urban areas. Long-term studies on both physical and emotional outcomes following ToP would be useful to assess any long-term sequelae after the procedure.

Declaration. Dr Vombo Mbona was a registrar who conducted this study for his MMed (O&G). Sadly he died in 2021 before publication of the results. He displayed great potential as a brilliant scholar and researcher. The article was completed in his honour.

Acknowledgements. We express gratitude to the dedicated sister-in-charge of the ToP clinic at Addington Hospital, Sr Laleetha Praemchand, for her assistance in seeing this entire research through till completion -an accolade she will share with all the study participants, without whom this project would not have seen the light of day. We also thank Mr Deepak Singh for his assistance with the statistical analysis.

Author contributions. VM designed the study with input from GK and HMS. GK monitored data collection and VM collected data for analysis, VM, GK and HMS analysed and interpreted the data and contributed to the manuscript. GK and HMS completed the manuscript and approved the version to be published.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. World Health Organization. Safe abortion. Technical and policy guidance for health systems. 2nd ed Geneva. WHO, 2012. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70914 (accessed 1 May 2019). [ Links ]

2. National Department of Health, South Africa. Standard treatment guidelines and essential medicine hst for South Africa. Primary healthcare level, 2020 edition. https://www.kznhealth.gov.za/pharmacy/PHC-STG-2020.pdf (accessed 1 June 2021). [ Links ]

3. Steyn C, Govender I, Ndimande JV- An exploration of the reasons women give for choosing legal termination of pregnancy at Soshanguve Community Health Centre, Pretoria, South Africa. S Afr Fam Pract 2018;60(4):126-131. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786190.2018.1432138 [ Links ]

4. Ndwanbi A, Govender I. Characteristics of women requesting legal termination of pregnancy in a district hospital in Hammanskraal, South Africa. South Afr J Infect Dis 2015;30(4):129-133. https://doi.org/10.1080/23120053.2015.1107265 [ Links ]

5. Poggenpoel M, Myburgh CPH. Womens experience of termination of a pregnancy Curationis 2006;29(1):3-9. https://doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v29il.1032 [ Links ]

6. National Department of Health, South Africa. Termination of Pregnancy Amendment Act (38 of 2004). Government Gazette No. 27267.129, 11 February 2005. https://wwwgov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/a38-04.pdf (accessed 1 June 2020). [ Links ]

7. Ngene NC, Ross A, Moodley J. Characteristics of women having first-trimester termination of pregnancy at a district hospital in KwaZulu-Natal. South Afr J Epidemiol Infect 2013;28(2):102-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/10158782.2013.11441527 [ Links ]

8. Frederico M, Michielsen K, Arnaldo C, et al. Factors influencing abortion decision-making processes among young women. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15(2):329. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerphl5020329 [ Links ]

9. Pies L, Popescu I, Margarit I, et al. Factors affecting the decision to undergo abortion in Romania. Experiences at our clinic J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):484-488. https://doi.org/10.111l/jep.13250 [ Links ]

10. As-Sanie S, Gantt A, Rosenthal MS. Pregnancy prevention in adolescents. Am Fam Physician 2004;70(8):1517-1524. [ Links ]

11. Munakampe MN, Zulu JM, Michelo C. Contraception and abortion knowledge, attitudes and practices among adolescents from low and middle-income countries. A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18(1):909. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3722-5 [ Links ]

12. Loi UR, Lindgren M, Faxelid E, Oguttu M, Klingberg-Allvin M. Decision-making preceding induced abortion. A qualitative study of womens experiences in Kis umu, Kenya. Reprod Health 2018;15(1):166 https://doi.org/10.1186/sl2978-018-0612-6 [ Links ]

13. National Research Council. Contraception and Reproduction. Health Consequences for Women and Children in the Developing World. Washington, DC. National Academies Press, 1989. https://doi.org/10.17226/1421 [ Links ]

14. Ceylan A, Ertem M, Saka G, Akdeniz N. Post abortion family planning counseling as a tool to increase contraception use. BMC Public Health 2009;9.20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-20 [ Links ]

15. Rocca CH, Samari G, Foster DG, Gould H, Kimport K. Emotions and decision Tightness over five years following an abortion. An examination of decision difficulty and abortion stigma. Soc Sci Med 2020;248:112704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112704 [ Links ]

16. Turner KL, Pearson E, George A, Andersen KL. Values clarification workshops to improve abortion knowledge, attitudes and intentions. A pre-post assessment in 12 countries. Reprod Health 2018;15(1):40. https://doi.org/10.1186/sl2978-018-0480-0 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

G Kistan

gaysheenkistan@gmail.com

Accepted 22 March 2023