Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.113 no.5 Pretoria may. 2023

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2023.v113i5.16784

IN PRACTICE

Medical internship training in South Africa: Reflections on the new training model 2020 - 2021

B RamoollaI; G van der HaarI; A LukeII; R KingIII; N JacobIV; B LukeV, VI

IMB BCh; Madwaleni District Hospital, Eastern Cape, South Africa

IIMB BCh; Bheki Mlangeni District Hospital, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIIMB ChB; Klerksdorp Tshepong Hospital Complex, North West Province, South Africa

IVMB ChB, FCPHM (SA); School of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

VMBBS, FRCP (Lon); Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

VIMBBS, FRCP (Lon); Department of Health, North West Province

ABSTRACT

The South African (SA) medical internship training programme model was recently revised to extend training into the primary care platform. In this article, we reflect on the experiences of training under the new model from an intern perspective. We use these reflections to make recommendations to the Health Professions Council of SA on how to further improve the training model by implementing systems that guide and empower the intern doctor practising at a primary level of care.

Medical internship training in South Africa (SA) was introduced by the Health Professions Council of SA (HPCSA) as a 1-year programme in the 1950s, followed by the introduction of a year of community service from 1999. As per the HPCSA guidelines, the purpose of medical internship training is for trainee doctors to complete their training under supervision in accredited facilities.[1]

Internship training should be comprehensive, and complement the SA healthcare system rooted within the primary healthcare (PHC) approach. This concept of PHC has been defined by three interrelated and synergistic components, comprising of meeting people's health needs through promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative and palliative care, by addressing social, economic, and environmental factors through policies, and then by empowering people and communities to optimise their health as self-carers and caregivers.[2] Training should provide the intern with exposure to a spectrum of clinical conditions, and develop skills in the management of common emergencies.[1]

The 2-year internship programme was initiated in 2006 following feedback that newly graduated medical doctors lacked certain skills and required more practical exposure in all the core medical disciplines.[3] The additional year would further accommodate the reduced undergraduate medical training from 6 to 5 years, which had begun in certain universities in SA at the time. It was premised that supervised practical experience in the major disciplines would compensate for the reduced undergraduate medical training years.[4] The reductions, however, were not implemented or reversed after implementation in all universities except the University of the Free State.

The current 2-year internship training programme takes place at accredited public health facilities with an unstandardised level of supervision provided in certain facilities by medical officers, registrars at academic hospitals and consultants. While the HPCSA guidelines do stipulate that training should be conducted under supervision, this is not always adhered to.[1] A detailed logbook records clinical competencies achieved at the end of the training period.

The training model from 2005 - 2019 offered 4 months in internal medicine, general surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology, and paediatrics, 3 months in family medicine, 2 months anaesthesia and orthopaedics and 1 month in psychiatry. From 2020, the training model was adapted to 3 months in internal medicine, general surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology and paediatrics in the first year of training. The second year of training consists of 6 months in family medicine (which is made up of 1 -month rotations in casualty, general outpatients, primary level facilities, district hospitals, ear, nose and throat, and ophthalmology), as well as 2 months each of orthopaedics, anaesthesia and psychiatry.[1] Casualty and outpatient department rotations take place at all levels of care, including tertiary hospitals, district hospitals and primary level facilities.

The aim of the current internship training model is to produce competent general practitioners with sufficient experience at all levels of care in order to strengthen the healthcare system. The model is designed to bridge the gap between undergraduate theoretical knowledge and the skills required to be a competent medical practitioner.[5] Since the initiation of the new training model in 2020, there has been limited research about the outcomes. Additionally, the new training model coincided with the COVID pandemic in SA, which further impacted training.

In this article, the authors have pooled together reflections on personal experiences of internship training under the new model, highlighting the perceived advantages and challenges experienced during our training, in order to make recommendations to the HPCSA on how to further improve the training model and improve health outcomes by strengthening the primary care platform. The first four authors commenced internship in 2020, after graduation from the universities of the Witwatersrand and Pretoria. Three of the authors completed internship at Klerksdorp Tshepong Hospital Complex in the Northwest Province, and the other at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital in Gauteng Province, both academic institutions in urban areas. We recognise that our reflections may not be representative, as intern experiences are likely to differ vastly depending on hospital and province. These reflections, however, provide a foundation for further discussion and action.

Discussion

Reflections on the advantages of the new training model

A major strength of the new training model was its emphasis on our ability to manage undifferentiated patients and refer appropriately. Spending a month in a primary level clinic and another month in a community healthcare centre strengthened our primary care skills. We were able to learn how to effectively manage patients at the first point of care and refer to appropriate facilities depending on the patients' needs. Serving as the only doctor at a clinic taught us skills beyond clinical medicine, such as teamwork, management skills and multidisciplinary collaboration to ensure that the facility functions appropriately. It also brought us closer to the communities we serve, creating more awareness of the social context of patients we treat at tertiary facilities, and the social determinants of health. Our experiences gave us insight into the inequities experienced by our patients, and challenges in accessing quality healthcare. Our involvement in antenatal care and family planning at primary levels of care further highlighted our role in health promotion and preventive care.

Another advantage of the new training model is completing the four core disciplines in the first year of training, thus ensuring a certain level of competence before moving onto the second-year disciplines.[1]

The month spent in district hospitals helped us gain independence. Catering to a larger population with fewer resources brought us closer to the reality of practising medicine in our country. The limited availability of equipment taught us how to be more innovative. At district level facilities, we learnt how to stabilise patients and arrange for transfer to a higher-level facility by consulting telephonically. The communication level required for transfer is an underrated practical skill that is not explicitly taught in undergraduate training or at tertiary facilities. We learnt that quick, precise and informative telephonic communication is essential for efficient transfer. We also learnt to practise good preventive medicine with appropriate healthcare screening. Working independently provided confidence and experience in the use of national guidelines and protocols. The district hospital environment prepared us for community service, where we could be expected to work independently in resource-limited facilities.

The month spent in casualty taught us valuable emergency skills and made us comfortable in providing acute care, including lifesaving procedures to undifferentiated patients in a high-pressure environment.

Reflections on the challenges of the new training model

Among the challenges of extending the duration of our family medicine rotation is the loss of 1 month of training each in internal medicine, general surgery, paediatrics and obstetrics and gynaecology. We felt that the shorter training duration in these disciplines limited our practical experience and opportunities to learn from specialists. We believe that the 4-month rotation helped cement specialised knowledge and increased the likelihood of retention of skills.

Unfortunatel,y there are no references to support the notion that a certain amount of time spent in a discipline would help to cement knowledge. However, healthcare practitioners retain theoretical knowledge for longer periods of time when compared with practical skills, which degrade quickly.[6] Therefore, longer periods of time are assumed to provide longer periods of exposure, and therefore improved competency in practical skills within a discipline.

Having an extended rotation in family medicine meant working for longer periods in resource-limited facilities. With that came the frustrations of not being able to provide the care and medication we were taught to provide, simply because we did not have the resources. Dealing with the infrastructure of the facilities outside our tertiary hospitals was also challenging - water and electricity were not always available, and we needed to adjust to working under such circumstances. However, exposure to these challenges reflects the realities of healthcare conditions around the country, and likely prepares us to manage these challenges during our community service year.

The main challenge with the new internship training model was the reality of being sent to facilities that were not necessarily ready to receive us. There was often inadequate orientation or a complete lack thereof, as well as inadequate supervision and training, as the staff at these facilities were not sufficiently prepared to teach and supervise intern doctors. We were often thrown into difficult situations where we had to function independently. Many interns have frightening stories of having to resuscitate a patient by themselves before a supervisor was available. This lack of adequate supervision is against HPCSA regulations, and must be addressed. According to the HPCSA guidelines, the ratio of interns to supervisors should be based on the ratio 4:1, and access to supervisors should be available 24 hours a day. [1] Challenges with the provision of adequate supervision to medical interns are not unique to the new training model, and are not limited to specific levels of care, but appear to occur more frequently at lower levels of care. There is no empirical evidence for this yet.

The COVID-19 pandemic notably impacted our experiences piloting the first 2 years of this new internship training model by exacerbating existing challenges and widening inequities in healthcare. While the pandemic itself provided a unique learning opportunity, specific competencies were affected, as outpatient experiences were limited, and training was focused on the management of inpatients with COVID. The need to rapidly adapt to a crisis laid bare the flaws within the healthcare system and the dire need to proactively build resilience to face crises adequately.

Recommendations: Opportunities to overcome challenges

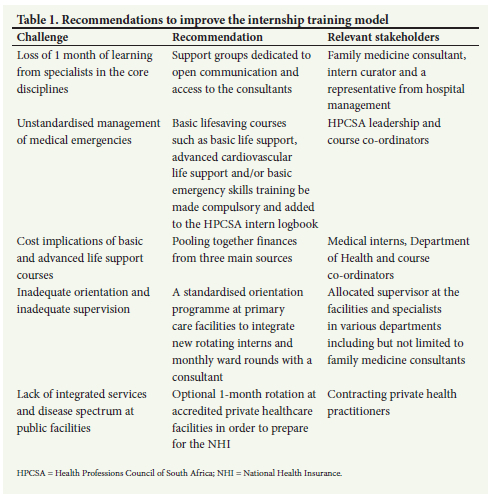

While the reflections described above are only from the intern perspective, we have several recommendations for broader stakeholder consideration (Table 1).

Specialist training and support

The loss of the 1 month of learning from specialists in the core disciplines could be addressed by support groups dedicated to open communication and access to consultants while working away from tertiary facilities. These support groups would be there for support and advice in times of need.

The support groups would comprise of a consultant, intern curator and a representative from hospital management. These groups may also provide support and mentorship to medical interns in coping in the workplace environment and debriefing after difficult clinical experiences, with the aim of promoting a culture of support. The support groups could guide interns throughout internship training, facilitating regular, structured support mechanisms regardless of the medical discipline or the facility.

Emergency preparedness

The way a medical intern performs in emergency situations in particular appears to be shaped by the medical university that the intern attended, and their internship training facility culture. This shows a need to standardise the management of medical emergencies. Allowing more time for practical skills and frequent refresher training is required to prevent adverse patient outcomes.[6] Adequate supervision, guidance and standardised emergency skills training are imperative given the varied undergraduate training experiences. We recommend that basic lifesaving courses such as basic life support, advanced cardiovascular life support and/or basic emergency skills training be made compulsory in internship and added to the HPCSA logbook. There is a greater need for interns to be independent and conduct basic lifesaving procedures independently, and these courses could help to bridge the current gap.[7] We recommend financing for these courses to come from three sources, namely the interns, a subsidy from the Department of Health and hopefully discounted rates from the course co-ordinators.

We firmly believe that implementation of these courses and these support groups during the early phase of the medical internship training programme across the country would support the training model by improving the quality of training and the quality of service delivery in peripheral areas during the family medicine rotation and community service.

Learning opportunities at primary care facilities

The challenge of working for longer periods in resource-limited settings should be met with innovative ideas and quality improvement projects with the assistance of family medicine consultants or public health physicians. These challenges should prepare us for the realities of rural community service, and highlight our role as health advocates to improve our healthcare system.

The challenge of inadequate orientation and inadequate supervision should be met with implementing systems that should include a standardised orientation programme at primary care facilities to integrate new rotating interns; an allocated supervisor at the facilities who is informed on the aims of the programme and is able to assist interns to navigate the system; and lastly, involvement of specialists, when available, to assist with monthly ward rounds in district hospitals to provide insight into patient management and give constructive feedback to district hospital doctors.

National Health Insurance preparedness

Another challenge that we are anticipating over the upcoming years will be the transition of our healthcare system to the National Health Insurance (NHI). The NHI is a health financing system designed to pool funds so that all South Africans can have access to quality affordable personal health services based on their needs.[8]

Although the new internship training model does prepare us by increasing our exposure to all levels of care, our earlier recommendation of mandatory emergency training courses would also contribute to improving emergency medical services delivery, which is a key component covered by the NHI.[8] Furthermore, our recommendation of incorporating more quality improvement projects under the guidance of family medicine consultants and public health physicians is another way to improve service delivery under the NHI.

We additionally recommend an optional 1-month rotation at accredited private healthcare facilities as an essential step in strengthening the PHC approach. Part of the NHI is to ensure integrated services by contracting private health practitioners to address the health needs of the population and reduce the burden of disease at public facilities. Exposure to the private healthcare system may further contribute to overall systems improvement.

Conclusion

Our internship experience has exposed the urgent need for health system strengthening in SA, particularly at primary levels of care. While our experiences are limited to the newly introduced internship training model, further research comparing the two models is needed to adequately evaluate the experiences of interns and the impact of the models of training on the healthcare system. A sufficiently powered study stratified by province and facilities across the country may provide a more representative evaluation of the new training programme. Qualitative studies to better understand intern and stakeholder issues in depth may further contribute to a richer understanding of contextual differences.

There is an obvious need within the new training model to strengthen intern doctors' ability to provide quality services. We hope that our recommendations may prompt further stakeholder engagement on feasible implementation methods. As junior doctors, we believe that our reflections may be used to motivate for research and improvement of the internship training model in order to prepare us sufficiently for community service, strengthen our health system and ultimately achieve health for all those we serve in our communities.

References

1. Health Professions Council of South Africa. Handbook on internship training. www.hpcsa.co.za/Uploads/MDB/Internship/22_Internship_Guidelines. Pretoria: HPCSA, 2022 (accessed 21 September 2022). [ Links ]

2. World Health Organization. A vision for primary health care in the 21st century: Towards universal health coverage and sustainable development goals. Geneva: WHO, 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/328065/WHO-HIS-SDS-2018.15-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed 21 September 2022). [ Links ]

3. Cameron BJ. Teaching young docs old tricks - was Aristotle right? An assessment of the skills training needs and transformation of interns and community service doctors working at a district hospital. S Afr Med J 2002;92(4):276-278. [ Links ]

4. Van Niekerk J. In favour of shorter medical training. S Afr Med J 2009;99(22):69. [ Links ]

5. Bola ST. The state of South African internships: A national survey against HPCSA guideline. S Afr Med J 2015;105(7):535-539. https://doi.org/10.7196/samjnew.7923 [ Links ]

6. Smith KG. Evaluation of staff's retention of ACLS and BLS skills. Resuscitation 2008;78(1):59-65. [ Links ]

7. Shrestha RBR. Basic life support: Knowledge and attitude of medical/paramedical professionals. World J Emerg Med 2012;3(2):141-145. https://doi.org/10.5847%2Fwjem.j.issn.1920-8642.2012.02.011 [ Links ]

8. National Department of Health, South Africa. National Health Insurance for South Africa, 2017. Pretoria: NDoH, 2017. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

B Ramoolla

botleramoolla007@gmail.com

Accepted 22 March 2023