Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.112 no.11b Pretoria Nov. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2022.v112i11b.16843

RESEARCH

The challenges of starting a tertiary orthopaedics centre in a rural area

M O MudauI; A B van AsII

IFC Orth (SA); MMed (Orth); Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Limpopo Academic Health Complex and School of Medicine, University of Limpopo, Polokwane, South Africa

IIMMed (Surg), PhD Division of Surgery, Limpopo Academic Health Complex and School of Medicine, University of Limpopo, Polokwane, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Rural areas are known to be less well resourced than urban areas. Starting new subspecialty centres in an urban area may be challenging; starting them in rural areas is often even harder. In this article we explore various factors that make starting a tertiary orthopaedics unit difficult. We first discuss the background, followed by general challenges of initiating specialised units in rural areas and then the more specific challenges with regard to orthopaedic surgery, and we finish by discussing some socioeconomic and family issues.

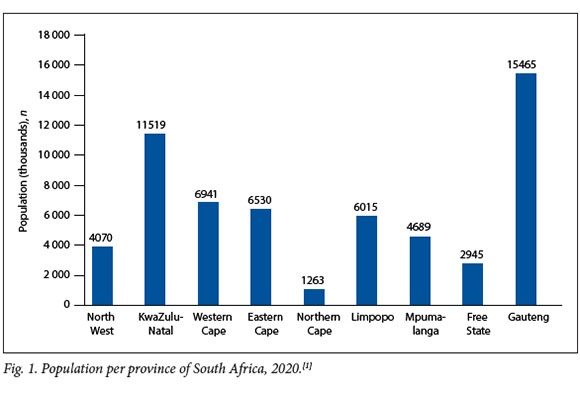

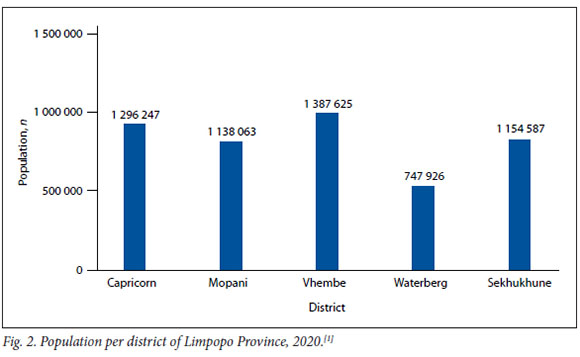

South Africa (SA) faces numerous socioeconomic challenges, ranging from poverty and unemployment to social injustices. Limpopo Province is SA's fifthlargest socioeconomic challenges, ranging from poverty and unemployment to social injustices. Limpopo Province is SA's fifthlargest province in terms of population (Fig. 1).[1] It comprises five districts, each with a substantial population (Fig. 2).[1] Some of the challenges faced by rural health practitioners are also encountered by health practitioners in urban areas, but the rural context increases these challenges,[2] often leading to social neglect of those areas that are regarded as the 'rural of the rural'. These communities continue to have poor access to clinics and hospitals for basic services, and most importantly, very limited access to tertiary services. Healthcare service delivery in rural areas is complex, with multiple challenges. According to Atkinson,[3] ~40% of the SA population resides in rural areas. The rural setting is characterised by availability of only a few health facilities, few health practitioners and lack of resources, all factors that compromise healthcare delivery. For healthcare to be effective, it should be widely available, of good quality and easily accessible. The international literature also reports negative trends in terms of rural healthcare, and difficulties in recruiting and retaining a skilled rural health workforce.[4] The National Center for Health Statistics in the USA published a report in 2004 in which US counties were classified according to their urbanisation level.[5] The unintentional injury mortality rate for the most rural counties was 54.1 per 100 000 population, a rate nearly two times higher than in counties with a predominantly metropolitan population. In rural areas that contained a small city, the rate was nearly 1.5 times higher (Fig. 3).

General challenges of starting a specialised surgical unit in a rural area

Most rural communities have poor access to health facilities owing to distance or lack of financial resources for transportation. Many people who live in rural areas are unemployed, increasing the difficulty of accessing healthcare. Health facilities in rural areas are generally set up specifically to provide basic primary healthcare.[6] Some of the health conditions faced by rural communities are similar to those in urban areas, and complicated cases require treatment at tertiary facilities. To increase access to tertiary health services, tertiary health centres may be built in rural areas, but this comes with its own challenges.[7] Rural areas have a high burden of trauma, which differs from trauma in urban areas. Trauma in rural areas is commonly due to pedestrianvehicle accidents, falling from wild fruit trees, falling on uneven surfaces owing to poor lighting, and animal bites.[8] Because of the lack of health facilities in rural areas, tertiary centres often apply an 'open-door' policy for all services, so patients who live close to a tertiary facility go there for treatment of health conditions that should ideally be attended to at primary healthcare level. This additional load increases the already large number of patients who need to be seen at central hospital emergency and outpatient departments, leading to substandard service delivery. The majority of patients who require tertiary services live far from the tertiary centres and rely on transportation provided by the provincial government toaccess the specialised treatment they need. This imbalance in tertiary access leads to delayed presentation and complicated surgical intervention, with subsequent increased complication, morbidity and mortality rates. Most rural regional and secondary hospitals have limited resources, including human resources, which further leads to inadequate support for those patients who require tertiary services and in turn increases waiting times and delayed presentation to the tertiary centres.

Specific orthopaedic surgical services needed in rural areas

Correctable congenital anomalies such as clubfoot, rickets and Blount's disease are often regarded as 'acceptable variants' in rural communities. Affected children therefore tend to grow up with these deformities, and unfortunately many of them remain disabled for life. Only few of them present to tertiary centres, typically very late, at a point where surgical correction may be detrimental. Rural communities are also known to have strong religious and belief systems. As a result, patients with conditions that require urgent tertiary intervention may only present to the tertiary service after a considerable delay due to religious and cultural beliefs.[9] In addition, many patients with septic and neoplastic conditions also present late, and often refuse surgical intervention as it is against their personal belief system. Many of these patients believe that witchcraft is the cause of their condition, and prefer to try traditional and religious healing before surgical intervention. This further perpetuates delay in providing an effective tertiary service to the community.

Tertiary orthopaedic procedures such as joint replacements, ligament reconstruction and spine procedures require very closely monitored rehabilitation and patient compliance after discharge. Compliance is likely to involve the patient needing access to clean water, proper ablution facilities, and flat surfaces on which to use walking aids. According to Badenhorst et al.,[10]-poor compliance is common in rural communities, and rehabilitation is also often poor owing to poor follow-up with physiotherapy and occupational therapy. It is well known that social and economic marginalisation of rural tertiary centres makes it difficult to recruit and retain specialists.'41 Tertiary centres in rural areas generally receive a limited budget, and the subsequent financial constraints limit the amount of equipment that the province can invest in. Many subspecialties may not be able to function without certain equipment, ranging from diagnostic machines such as magnetic resonance imaging scanners to interventional equipment such as arthroscopic instruments.

Socioeconomic and family issues

Most specialists and their families would rather live in big cities with better facilities, including schools, and a wider range of entertainment options than are available in rural areas. Rural tertiary centres therefore depend on relatively few specialists who are expected to provide service delivery to hospitals, including district hospitals (Table 1). In addition, these specialists are expected to teach both under-and postgraduate students. This overwhelming academic load together with the service delivery responsibilities can easily result in overworking of personnel.[11]

Finally, there is only a limited relationship between private and public services in most rural areas. This lack of inter-relations limits exposure of personnel to the different dynamics of both private and public health facilities, while precluding private practitioners from assisting with teaching and training of under- and postgraduate students.

Conclusion

There is a significant shortage of specialised surgical units in rural areas, affecting rural patients in terms of prognosis, morbidity and mortality. Apart from typical general factors that make it difficult to start up subspecialist units in rural areas, initiating an appropriate orthopaedic surgical service for correctable congenital abnormalities, as well as for septic and neoplastic conditions, is specifically adversely influenced by religious and belief systems prevalent in rural areas. These factors aggravate a situation already compromised by poor socioeconomic conditions and transport problems.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. None.

Author contributions. Equal contributions.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Statistics South Africa. General Household Survey 2020. Statistical release P0318. Pretoria: Stats SA, 2021. https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0318/P03182020.pdf (accessed 31 October 2022). [ Links ]

2. Nielsen M, D'Agostino D, Gregory P. Addressing rural health challenges head on. Mo Med 2017;114(5):363-366. [ Links ]

3. Atkinson D. Rural-urban linkages: South Africa case study. Working Paper Series Document No. 125. Working Group: Development with Territorial Cohesion, Territorial Cohesion for Development Program. Rimisp, Santiago, Chile, 2014. https://www.rimisp.org/wp-content/files_mf/1422297966R_ULinkages_SouthAfrica_countrycasestudy_Final_edited.pdf (accessed 19 October 2019). [ Links ]

4. Abelsen B, Strasser R, Heaney D, et al. Plan, recruit, retain: A framework for local healthcare organizations to achieve a stable remote rural workforce. Hum Resour Health 2020;18(1):63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-00502-x [ Links ]

5. Eberhardt MS, Pamuk ER; National Center for Health Statistics, USA. The importance of place of residence: Examining health in rural and non-rural areas. Am J Public Health 2004;94(10):1682-1686. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.94.10.1682 [ Links ]

6. Gray A, Vawda Y, Jack C. Health policy and legislation. In: Padarath A, English R, eds. South African Health Review 2011. Durban: Health Systems Trust, 2011:1-15. https://www.hst.org.za/publications/South%20African%20Health%20Reviews/sahr_2011.pdf (accessed 2 November 2022). [ Links ]

7. Gaede B, Versteeg M. The state of the right to health in rural South Africa. In: Padarath A, English R, eds. South African Health Review 2011. Durban: Health Systems Trust, 2011:99-106. https://www.hstorg za/publications/South%20African%20Health%20Reviews/sahr_2011.pdf (accessed 2 November 2022). [ Links ]

8. Edem IJ, Dare AJ, Byass P, et al. External injuries, trauma and avoidable deaths in Agincourt, South Africa: A retrospective observational and qualitative study. BMJ Open 2019;9(6):e027576. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027576 [ Links ]

9. Thomas T, Blumling A, Delaney A. The influence of religiosity and spirituality on rural parents' health decision making and human papillomavirus vaccine choices. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 2015;38(4):E1-E12. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0000000000000094 [ Links ]

10. Badenhorst DHS, van der Westhuizen CA, Britz E, Burger MC, Ferreira N. Lost to follow-up: Challenges to conducting orthopaedic research in South Africa. S Afr Med J 2018;108(11):917-921. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2018.v108i11.13252 [ Links ]

11. Malelelo-Ndou H, Ramathuba DU, Netshisaulu KG. Challenges experienced by health care professionals working in resource-poor intensive care settings in the Limpopo province of South Africa. Curationis 2019;42(1):a1921. https://doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v42i1.1921 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

M O Mudau

drmudaumo@gmail.com

Accepted 3 October 2022