Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.112 n.7 Pretoria Jul. 2022

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2022.v112i7.16644

IN PRACTICE

HEALTHCARE DELIVERY

Thematic analysis of the challenges and options for the Portfolio Committee on Health in reviewing the National Health Insurance Bill

G C SolankiI, II, III; N G MyburghIV; S WildV; J E CornellVI; V BrijlalVII

IBChD, DrPh; Senior Specialist Scientist, Health Economics, Health Systems Research Unit, South African Medical Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa

IIBChD, DrPh; Honorary Research Associate, Health Economics Unit, School of Public Health and Family Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIIBChD, DrPh; Principal Consultant, NMG Consultants and Actuaries, Cape Town, South Africa

IVBDS, MChD; Faculty of Dentistry and World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Oral Health, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town South Africa

VBSocSci Hons (Justice and Transformation); Postgraduate student, MPhil Public Law, University of Cape Town, South Africa

VIMA, PhD: Director of Institutional Development and Planning (retired), Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance, University of Cape Town, South Africa

VIIBCom (Law, Economics), MSc (Economics); Senior Director, Clinton Health Access Initiative, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The Portfolio Committee on Health (PCH) obtained public input on the National Health Insurance Bill (the Bill) from a wide array of individuals and organisations between May and September 2021. The record of these submissions collated by the Parliamentary Monitoring Group provided the source material for this article. The concerns, suggestions and other issues raised by respondents were analysed to determine what challenges and options the PCH needs to take seriously as they prepare the Bill for Parliament. Prominent issues raised included concerns about the proposed governance structure, flaws in the funding model, the risk of corruption, the constitutional and human rights at risk, limited access to care for several groups, and the unresolved nature of the medical benefits to be provided under the Bill. Future legal contestation of the Bill on several of these issues has the potential to stop or delay its implementation for a long time. The PCH has some hard decisions to make: whether to address these concerns with quite radical revisions of the bill, to omit problematic elements, or to leave it unchanged, and accept the contestation this will bring.

The National Health Insurance Bill[1] (the Bill) was introduced in Parliament in August 2019. Parliament's Portfolio Committee on Health (PCH) is responsible for obtaining public input on the Bill, reviewing it based on these inputs, and preparing a final version for the Minister to present to the National Assembly. The PCH conducted public hearings across the country, received over 100 000 submissions, and heard oral presentations from 117 respondents between 18 May 2021 and 23 February 2022.

The research presented in this article aimed to provide a thematic analysis of the concerns raised and the suggestions made, and to outline the challenges and options for the PCH in responding to these inputs.

Information on the PCH hearings was obtained from the Parliamentary Monitoring Group (PMG),[2] which provides information on all parliamentary committee proceedings in the form of detailed, unofficial minutes, documents and sound recordings of meetings. The meeting summaries and the presentations and submissions of 117 respondents available on the PMG website were captured into a database and analysed. The database was structured to capture information on the data capture process (data capturer, checker and reviewer), respondent information (organisation, date presented), and inputs provided by theme (support for National Health Insurance (NHI), concerns around corruption, governance and the Minister of Health (MoH), constitutional infringements, funding, access and benefits).

To make the analysis publicly available as soon as possible, an editorial'31 and an 'In Practice' article[4] were published in the South African Medical Journal (SAMJ) and a series of op-eds, each covering a key theme, were published in partnership with the Daily Maverick[5-12] These earlier articles cover the inputs in detail, while this article provides an overview of the entire series. It addresses concerns about the proposed governance structure, the constitutional and human rights, funding, corruption, access to care, and medical benefits to be provided.

Support for the Bill

Support for the Bill emerged as a recurrent theme at the hearings, particularly in the questioning of respondents by members of Parliament following the presentations. The data showed that: (i) many respondents support the goal of achieving universal healthcare (UHC) but not the NHI (Fund) as outlined in the Bill; and (ii) while there is broad support for the aim of the Bill (attaining UHC), many doubted that the strategy set out in the Bill could deliver on this aim.[6]

Respondents could be defined by level of support for the Bill:

(i) those who have unequivocally come out in support of NHI;[13,14]

(ii) those who were unequivocally against the Bill;[15-17] and (iii) those whose support for the Bill was ambivalent, with most in this group declaring support for UHC or the aims of NHI, but conditional or unclear in their support for NHI per se.[18-20] For instance, the National Planning Commission (NPC) stated that it 'supports the key policy principles essential for universal health coverage reform, [that is] mandatory contribution, pooling of funds and strategic purchasing to promote efficiency and accountability'.[18] However, it cautioned that 'the NPC sees the Bill as a step in the right direction, but it submits that the Bill in its current form is lacking in critical detail in some important areas and contains provisions that are problematic'.[18] To assess the overall level of support and the nuances in the level of support, we compared the level of support for UHC and the level of support for NHL While 90.6% of respondents supported UHC, just 1.7% opposed it and 7.7% were conditional/unclear, compared with 25.6% who supported NHI, 27.4% who opposed it and 47.0% who were conditional/unclear

This broad support may reflect endorsement of an aspirational but undefined goal of UHC, as neither the Bill nor respondents clearly define UHC. However, there are divergent opinions on how to achieve that goal, and these concerns are discussed below.

Governance

Concerns about governance, specifically related to the role and powers of the MoH, featured prominently at the hearings and were examined in detail in an earlier SAMJ publication.[4] The key issues are summarised here.

In total, 123 clauses in the Bill refer to the MoH. The Bill makes the MoH responsible for overall governance and stewardship of the Fund (clause 31(1)), requiring the Fund to 'account to the Minister for the performance of its functions and the exercise of its powers' (clause 10(l)(m)). Respondents were concerned that the proposed governance structure concentrates power in the Minister, lacks separation between the political and operational spheres, weakens the role of the Board, does not adequately ensure its independence, and undermines transparency and accountability.[21,22] Concerns were also raised regarding the relationship between the CEO and the Minister (section 21).[19]

The proposed amendments can be grouped into three categories: (i) those that call for Fund reporting and accountability to shift from the MoH to Parliament; (ii) those that accept that the Fund and Board have to account and report to the MoH, but call for amendments to limit the manner and extent to which the MoH can exercise the powers vested in him/her; and (iii) those that call for the Board appointment/removal processes to be reviewed.

Changing accountability from the MoH to Parliament

Several respondents called for this shift in accountability[23-26] This is a significant challenge for the PCH. Section 9 of the Bill establishes the Fund as 'an autonomous public entity, as contained in Schedule 3A to the Public Finance Management Act'. By law, such entities are accountable to the relevant executive authority, in this case the MoH. The Fund can therefore not be made accountable to or report directly to Parliament.

Enshrined in the Constitution is the principle of 'separation of powers'.[27] In South Africa (SA), only Chapter 9 Institutions are directly accountable to Parliament.[27] NHI is not being established as an entity to safeguard democracy, and it would therefore be difficult to justify Chapter 9 status.

Shifting reporting and accountability lines to Parliament requires a significant change in the Constitution and in the objectives of the Fund, in turn requiring further public participation and comment. This 'back-to-the-drawing-board' approach would effectively negate the lengthy process of engagement, drafting and re-drafting initiated with the release of the Green Paper on NHI in 2011,[28] and probably cause discord among supporters of the Bill. The PCH will need to carefully consider the viability of direct parliamentary oversight of NHI, given poor parliamentary oversight of public organisations such as Eskom, the SABC, Telkom, the Public Protector's office and SARS. Parliament has been slow to act, unable to decide, or unwilling to execute the corrective measures required.

Retain accountability to the MoH but delegate power to the Fund

To effect this shift, respondents called for complete authority for Fund stewardship to be assigned to the Board[15,19,22,29] and CEO,[22] with rules to ensure Fund independence from political influence in its decisions. The Board of Healthcare Funders (BHF)[19] proposed three levels of accountability: to Parliament at a macro level, to the MoH in accordance with the Public Finance Management Act (PFMA),[30] and to the Prudential Authority for financial institutions, based in the Reserve Bank. The South African Human Rights Council suggested that direct accountability to the MoH be retained on issues related to policy formulation (political governance), but that amendments be considered for clauses related to operation and administration (Board governance).[21] Treasury's Annual Report Guide for Schedule 3 and 3c Public Entities[31] would guide this. Section 52 makes provision for the Minister to delegate functions to the Fund. With minor wording changes, the PCH could amend the Bill to devolve more power to the Fund.

Review appointment/removal processes

Respondents called for the Board to be appointed by Parliament and not the Minister to make these processes more open and democratic.[19] Appointment and removal processes of Fund office-bearers (CEO, Board, advisory and appeals committees, etc.) should be similar to those in Chapter 9 Institutions, which involve the National Assembly[15,19,21,22,25,26,29] The size of the Fund warrants dual accountability to the MoH and the Minister of Finance, and both ministers should have a representative on the Board.[29]

It would be difficult for the PCH to move control of these processes to Parliament, but they could shift them from the sole oversight of the MoH into a more 'institutionalised' process such as requiring the MoH to establish a public appointment process, publishing guidelines on who may serve, and ensuring civil society representation. The PCH could do this via wording changes to the Bill.

Accountability within democracy

PCH members pointed out that the powers of the MoH currently contained in the Bill arose from the Constitution,[27] which gives democratically elected political parties the right to pass legislation they deem necessary and to appoint people to certain roles in government to advance their policy goals and objectives. However section 2 and section 44(4) of the Constitution state that, in exercising its legislative authority, Parliament 'must act in accordance with, and within the limits of, the Constitution, and the supremacy of the Constitution requires that 'the obligations imposed by it must be fulfilled'. In addition, section 167(4)(b) confers exclusive jurisdiction on the Constitutional Court to decide the constitutionality of any parliamentary or provincial bill.

Constitutional issues

With the exception of the African National Congress (ANC),[32] which argued that it was 'satisfied that the Bill is constitutional, having witnessed the rigorous evaluation of constitutional implications of its underlying policy when that was processed through the Cabinet', respondents expressed a high level of concern about the constitutionality of the Bill, with just over two-thirds (69%) concerned, 27% 'silent' and only 3% not concerned. The concerns focused on the limitation of rights resulting from a 'single-purchaser-single-payer' model, infringements on the constitutional responsibility of provinces, non-compliance with the 'rule of law' principle, and exclusion of care for migrants and refugees.[10]

Infringement on the Bill of Rights

The Bill designates the NHI Fund as the 'single purchaser and single payer' for healthcare services. The BHF said that this 'makes it unlawful for people to purchase health care service that are covered by NHI except in very limited circumstances'.[19] This limitation infringes the Bill of Rights (chapter 2) of the Constitution[27] in two ways.

A single-payer-single-purchaser system infringes on the right of access to healthcare services as provided for in section 27 of the Bill of Rights, and this limitation does not meet the 'reasonable and justifiable' requirements of section 36. It would be unconstitutional to restrict the healthcare purchasing choices of those who can afford them, or to prevent patients from accessing services they need, but that are unavailable through NHI because of resource constraints.[19,33,34] This was globally unprecedented, with most developing countries with universal health cover allowing for a dual system, where citizens pay taxes for healthcare but also have the option to pay for private healthcare should they wish to do so.[35]

Section 27 of the Bill of Rights imposes a 'positive' obligation on the state to realise the right of access to healthcare within the states available resources and a negative obligation not to take steps that are retrogressive. Given the high risk of the Bill not achieving its objectives, the state could fail in its positive obligation, and if the Bill results in reduced access to healthcare services, the state would also fail in its negative obligation.[36]

Legal precedents have established that it is an infringement of rights if patients are limited to the public sector when the specialised care they require is only available in the private sector,[37] or if the public health system cannot provide adequate care within a reasonable time.[38] Several respondents[13,18] called for section 6(0) of the Bill to be 'amended in order to preserve the rights of citizens to purchase any health service benefits through a voluntary medical insurance scheme, ... or out of pocket payments ...'.[39] Restrictions on choice of provider must therefore be removed.[23,34,40,41]

The Constitution requires any limitation to be reasonable and justifiable in an open society',[27] the key characteristic of which is 'individual freedom or autonomy'. The Bill limits this freedom.[42]

Infringement of provincial responsibility

The single-purchaser/payer provision of the Bill infringes on the constitutionally mandated responsibility of provinces and other tiers of government 'to ensure the progressive realisation of the right of access to health care services' as set out in chapter 4 of the Constitution.[27] The Bill does not permit the provinces to purchase healthcare services[19] and significantly reduces the scope of work and powers of the provinces as set out in the Constitution,[27] the National Health Act[43] and the PFMA.[30] The Bill should therefore be amended to allow provinces and local government to continue playing their roles.[24-26,44-46]

Conflict with the rule of law

The language of the Bill creates uncertainty, contrary to the principle of the 'rule of law', a founding value of the Constitution.[19,47] The

BHF pointed out that the rule of law requires that 'legislation must be stated in a clear, accessible and reasonably precise manner, and that there must be a rational relationship between a scheme adopted by a legislature and the achievement of a legitimate government purpose',[19] and that '... the NHI Bill is poorly drafted. It contains several internal contradictions, shows a poor understanding of the legal principles of legislative drafting and a lack of insight into how language must be used when writing law. It conflates policy principles with legal principles, which causes uncertainty to creep in when reading the bill. There is no recognition that one cannot write all policy into legislation. Some policy should remain just policy. This makes understanding the bill difficult and confusing at times.'[19]

Rights of asylum seekers and migrants

The exclusion of asylum seekers and migrants from NHI benefits was unconstitutional and counterproductive. Section 7 of the Bill of Rights applies to all people in our country', and section 27 allows for everyone' to have the right to access healthcare (and does not exclude persons on the grounds of their status as asylum seekers).[42] The Bill places SA at risk of violating the non-refoulment principle if asylum seekers are forced to leave because of failure to access healthcare.[48] The health of the nation was influenced by the health of all within the country. Excluding any inhabitants of SA was counterproductive, fuelled the spread of disease and added to the burden of disease.[49,50]

It was essential to adopt a clear principle of non-discrimination in the application of NHI and the inclusion of asylum seekers, undocumented migrants, students, and all children as beneficiaries.[21,51-54]

Funding

Globally, there is a range of healthcare funding models, from those relying mainly on private funding (individuals pay out of pocket or purchase private insurance) to those relying on public funding (from tax contributions).[7]

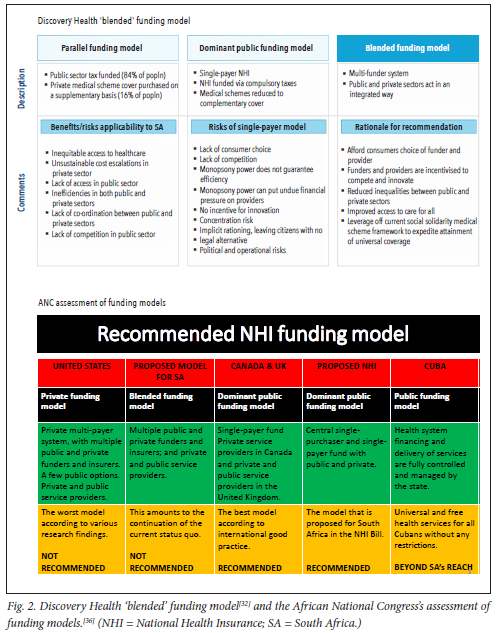

SA currently operates a 'parallel' funding model with -44% of healthcare expenditure funded by tax-based state funding, 48% by individuals via private medical aids, and 8% by out-of-pocket' payments. The Bill envisages moving to a 'dominant public funding' model by moving 'private funding' to 'public funding' (Fig. 1). Public funding would increase (mainly via an increase in taxes), while private funding would decrease, as NHI is expected to cover all or most healthcare needs and expenditures, and private medical aids may only be allowed to cover benefits excluded by NHI.

Support for the NHI funding model

Those backing the Bill see the NHI funding model as the mechanism to address inequities and inefficiencies in SA healthcare (Fig. 2). The ANC[32] claims: 'National Health Insurance is a health financing system designed to pool funds and actively purchase services with these funds to provide universal access to quality, affordable personal health services for all South Africans based on their health needs, irrespective of their socioeconomic status.' Underlying their support is the view that the shift to a 'public-dominant' funding model will translate into greater public control of health financing, a better-integrated healthcare system, greater cross-subsidisation, concentrated purchasing power and enhanced purchasing efficiency.

The question of how public funding will be increased to -8% of the GDP is contentious. Section 49 of the Bill states that NHI will be funded from the reallocation

of medical scheme tax credits, general tax revenue, payroll tax and a surcharge on personal income tax. Among supporters of the Bill, there is widespread support for the reallocation of medical scheme tax credit funding, with the National Education, Health and Allied Workers' Union[55] arguing that as part of funding for the NHI, government should completely end tax rebates to medical scheme holders ... government should redirect tax rebates towards the NHI fund'. However, views were mixed on the issue of increased taxation. The ANC[32] endorsed the sources of funding listed in the Bill and called for 'the money currently available in the public and private sector for personal health services [to be] supplemented by money from the fiscus', arguing that this debunks the myth of extra taxation. The Congress of South African Trade Unions,[56] on the other hand, called for extra taxation, arguing that 'the tax net will need to be expanded and made more progressive and new taxes targeted at the wealthy'. They further argued for mandatory enrolment and pre-payment; a payroll tax on employers; a progressive tax on wages, financial assets and investments of the wealthy; tax on inheritance and estate duties; and taxes on luxury imports, currency transactions and financial transactions.

Concerns with the NHI funding model

Opponents of the NHI funding model raised five concerns.

First, the Bill did not provide sufficient detail on how the funds will be raised,[18,33] or how the financial viability of the Fund will be ensured.[57]

Second, the proposed increase in taxation was unaffordable or unsustainable.[46] The increased taxation (4.1% of the GDP) required to shift the ZAR212b currently spent by 9 million South Africans on medical aid cover from 'private' to 'public' is unlikely to be feasible.[39] Removal of medical tax credits would release funding of ZAR26 - 29b, but leave a substantial shortfall to be funded through increased taxation. The affordability of NHI, given the projected ZAR380b deficit in the main budget framework, was questioned.[42]

Third, there was a belief that a public-dominant funding model would not work in SA. The single-payer model would reduce consumer choice, competition and efficiency put undue financial pressure on providers, concentrate risk, lead to implicit rationing, and carry political and operational risks.[39] 'It is unclear how the fund will be protected from theft, mismanagement, and corruption. A pooled fund will not equate to improving the efficiency of the healthcare system ... The DoH should focus on fixing governance and management structures to increase efficiency and accountability of the public healthcare system before considering an NHI.[42] The NPC was of the view that 'The Bill appears to be drafted on the assumption of a perfectly efficient, ethical, and capable state, and tends to ignore the reality of inadequate public health care services.[18]

Fourth, the Bill did not make clear how funding will flow to providers. The Bill does not address the payment of funds to provincial health departments and municipalities for services they render There was no distinction between health services they were constitutionally obliged to fund, and NHI-funded services. Provincial health departments are responsible for health service delivery in terms of schedule 4 (health services) and schedule 5 (ambulance services) of the Constitution. While the Bill makes provision in the schedule for laws to be amended, the Constitution cannot be amended in this manner.[19]

Fifth, there were better funding models than the one proposed. A blended model, with a multi-funder system in which the public and private sectors act in an integrated manner, was proposed,[39] and is shown alongside the ANC's assessment of funding models in Fig. 2.

Corruption

Concerns about corruption featured prominently at the hearings. Over half (56%) of respondents expressed concerns, 43% were 'silent on this issue and only 2% felt that corruption was not a concern.[8]

Of the few respondents who were not concerned, the ANC said that 'systems and processes that mitigate against corruption are in place'.[32] The Government Employees Medical Scheme (GEMS) felt confident that corruption would be kept in check because 'section 20(2e) will establish an investigating unit within the national office of the NHI fund for the purpose of investigating fraud, corruption and other criminal activities'.[58] GEMS felt that the narrative that state-owned enterprises are always run badly is not true and that GEMS was an example of a well-run state institution.[58] Most respondents were concerned that corruption threatened NHI capacity to meet its stated objectives, noting a culture of corruption and incompetence that has led to poor management, underfunding, understaffing, a loss of skilled staff and deteriorating infrastructure in the public sector that would be replicated and/or enhanced in the NHI environment.[42,59]

Respondents highlighted five features that place the proposed NHI at risk of corruption: (i) government lacked the will to deal with endemic levels of corruption;[60,61] (ii) the Bill lacked detail on how corruption will be prevented;[62] (iii) NHI enhanced opportunities for corruption by concentrating funding and decision-making;[42,63,64]

(iv) the corporate governance of the Bill was weak,[19] concentrated too much power in the hands of the MoH without providing the necessary oversight over the planned massive resources of the NHI,[19,21,26,65-68] and offered 'myriad opportunities for corruption and looting, particularly in areas where contracts are entered into';'[21] and (v) the proposed safeguards to manage corruption were inadequate, with respondents pointing out that the envisaged corruption-fighting investigating unit (clause 20(2)e) will be ineffective if the corruption develops within the NHI Fund itself, as the unit will be unable to confront internal corruption.[16,34,42]

Some felt that 'Without fixing the issue of corruption no system will be sustainable', implying that NHI should not be considered until corruption and other concerns are addressed.[35] Others made troad' recommendations calling for stronger governance structures, better management, greater accountability and greater enforcement of controls over corruption.[21-23,67] The South African Communist Party argued that 'the NHI Fund must have inbuilt mechanisms to fight corruption. This should include efforts to ensure greater transparency and accountability, including the use of public funds and ensuring they are directed to those who need them most.[69]

More specifically, respondents recommended that the Bill clarify the role of provincial departments relative to the National Ministry of Health, the mechanisms the Minister will use for NHI expenditure control, the role of health ombudspersons,[70] and the 'fit and proper person requirementfor Boardmembers.'251 Respondents recommended that the Fund be made directly accountable to Parliament and not the MoH, that the Minister's powers be reduced,[26,71,72] and that Parliament play an oversight role, as it does for Chapter 9 Institutions.[73]

Use of a judicial panel was recommended[74] for appointment of the Board rather than the discretion of the MoH,[29] rendering persons with criminal records or prior convictions for fraud or corruption ineligible.[54] Greater civil society and organised labour representation on the NHI Board and other structures was proposed.[20,56,65,66]

Calls were made for public access to information[45,51] and for adherence to the Global Initiative for Fiscal Transparency (GIFT) Principles of Public Participation, especially in relation to access to information.[75] Respondents also called for the incorporation of the Presidential Health Summit Compact recommendation on whistle-blowing,[16] for the inclusion of penalties to discourage abuse,[14,76] and for the anti-corruption unit to be independent of the Fund as 'the Fund cannot investigate itself and must be subject to external scrutiny.[70,77]

On procurement, respondents recommended the adoption of National Treasury's provision of transversal contracts, which provided a very transparent process; everyone knew who the players were, and the pricing structures' and 'balanced the need to prioritise Black-owned companies and mitigate the risk of abuse'.[78] Respondents also recommended decentralisation of the strategic purchaser role to the provinces.[79]

Access

Chapter 2 of the Bill sets out the rules regarding access to the healthcare services covered by the Fund, including eligibility and conditions for Fund cover, the requirement for users to register, the rights of Fund members, and health services and costs covered by the Fund. Respondents recorded concerns on all sections.[11]

Eligibility and registration

The exclusion in section 4 of asylum seekers and 'foreigners' is addressed in the section above on constitutional concerns. The definition of an employee eligible for Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act benefits is wider than that proposed for NHI, so users (employees) injured or diseased in the course of employment may be excluded from legitimate benefits.[80]

Section 5 of the Bill requires eligible individuals to register at an 'accredited health care service provider or health establishment' and to provide biometrics, fingerprints, photographs, proof of place of residence, ID card, original birth certificate or refugee card. These requirements would deny access to care to users without complete documentation[22,70,72] and put children without birth certificates at risk.[81] Inefficient registration processes would lead to 'unnecessary waiting periods'.[23] The uneven geographical distribution of clinics would make registration difficult for rural populations, the elderly and disabled people, exacerbating inequalities.[66]

Recommendations included the incorporation of explicit provisions in the Bill for registration of users without documentation to protect their right to access healthcare services.[22] Other forms of identification must be recognised[21] and alternative mechanisms created for children to register as users when the assistance of a parent or guardian is unavailable.[51] Users not in their geographical area of registration must be able to register.[72]

Referral pathways

Section 7 of the Bill requires users to attend NHI-registered providers and adhere to prescribed referral pathways or be liable for the cost of care.

The prescribed referral pathways conflict with the Patients' Rights Charter,[82] which makes provision for the right of patients to choose their own healthcare provider or health facility.[83] Referral pathway rules would prevent people from continuing a relationship with their doctor of choice,[35] and were 'prejudicial to pregnant women who prefer to engage their regular gynaecologist or obstetrician'.[84]

Referral pathways placed continuity, quality and efficiency of care at risk,[83] especially for patients with complex conditions or longstanding chronic conditions.[47,85] There would be unnecessary waiting periods,[23] and 'access delayed may be access denied'.[47]

The prescribed referral network could limit access to care. There was a lack of clear guidelines for referral of persons with disabilities and their families from rural areas to a designated state hospital, and no recognition of their need for transport and accommodation.[86] This could limit coverage and/or increase costs for users who had to travel to other facilities because their nearest facility was not accredited.[25,54]

Mechanisms were needed to safeguard patients transferred outside the pathways for specific reasons, with some degree of choice available to patients in consultation with the referring doctor.[87] Patients should not be refused treatment under this section on financial grounds, and there needs to be an appeal mechanism. The referral pathways needed to be user-friendly, to include all health providers and establishments, to provide for up- and down-referrals from primary healthcare to tertiary care, to involve clinicians in their creation, to be defined to ensure equity, and to be evidence based and regularly updated.[88] The Bill should clarify how users could access services when they are unable to access the healthcare providers or facilities with which they have registered.[89]

Lobbying

Numerous groups lobbied for the NHI to include access to specific services, or for the inclusion of specific benefits related to their constituencies. Most of these organisations focused exclusively on lobbying for their interests and made no other comments on the Bill, arguing, for example, that 'the elderly should be regarded as a separate target group just as children, refugees and inmates are mentioned specifically',[90] that priority should be given to South African Police Service members,[91] people with disabilities,[53] cancer patients,[23] or mental health services for children and adolescents, and that there should be improved access to forensic mental health services.[70] The PCH faces a challenge to reconcile the passionate demands of special interest groups with the NHI brief to serve the interests of population health.

Benefits

The benefits to be covered by NHI and the process for defining them gave rise to concern.[12] Clause 25(4) of the Bill provides for the Benefits Advisory Committee (BAC) to review NHI benefits and services and, in consultation with the MoH and the Board, determine healthcare benefits the Fund will provide.[1] Most respondents supported the Bill's aim to progressively realise UHC,[6] and some viewed NHI as the mechanism that 'would allow for people to access health care services without incurring any financial hardship'.[55] Others were concerned by the 'open-ended' nature of clause 25(4), the lack of detail, affordability, the level at which they would be offered, and the process of deciding the benefits package.

Clarity, affordability and level of benefits

NHI needed to 'spell out' the benefits package,[35,47] clearly stating what would be excluded and how excluded benefits would be paid for.[13] The South African Medical Association stated that it was extremely difficult for health practitioners to support the NHI reforms, not knowing what will be available to patients, or under what conditions'.[34]

'Given the budgetary constraints, NHI is likely to cover a much narrower range of services than what is currently provided by medical schemes',[67] and rationing benefits to a level lower than currently available benefits will compromise patient care and health outcomes.[92] The University of the Witwatersrand[46] pointed to the findings of the Ministerial Task Team on Social Health Insurance (2005),[93] which concluded that '... even with a minimum benefit, costed at the lowest level feasible, it appears not to be affordable in the medium-term. Overall health expenditure would rise to exceed 11.3% of GDP'

Deciding on benefits

NHI success may depend on the extent to which the Fund is able to successfully manage, within funding constraints, the inevitable trade-offs between types and comprehensiveness of different benefits. It would be extremely challenging to create an affordable list of benefits, and the medicolegal risks associated with getting this wrong are high.[26]

The Bill also did not make clear the criteria for determining the benefits package, and there is a lack of clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, a lack of clarity on meaning and intent of phrases such as 'medically necessary' or comprehensive', and a lack of principles or guidelines within which the BAC would be required to act.[47]

While some of the benefits may need to remain implicit, the Fund should be explicit about the main health benefits to be covered, referral pathways, essential medicine and laboratory lists and clinical guidelines, as well as areas of 'disinvestment' - benefits that the Fund would not cover.[26] A 'transparent process [is needed] for determining the benefit package, taking into account access, quality and affordability'.[36] The governance processes of the BAC and the Health Services Pricing Committee must be defined[94] and their recommendations made binding.[47] The underlying principles for determining comprehensive' or 'necessary' care should be clarified.[95] Affordable' universal access must be defined within the legal mandate of the Fund.[96] 'Basic health services' must be clearly defined in line with the Constitution and accepted international standards[21] and be evidence based.[47,97

The Bill focuses on personal health services and neglects services related to the broader social determinants of health, disease prevention and health promotion. This contradicts the principles related to addressing social determinants of health outlined in the NHI White Paper' and reflects the 'extremely narrow' conceptualisation of prevention and promotion in the Bill. It is recommended that the Bill place greater emphasis on 'inter-sectoral action to support health promotion, disease prevention and address the social determinants of health.[22,59,98]

Key issues for PCH consideration

The extensive powers accorded the MoH were a concern across a wide range of stakeholders, including some who support NHI. Governance failures across the country and recent improprieties by the MoH have heightened these concerns.[99-101] The need for robust governance structures has been missing from UHC conversations.[102] When they are weak, healthcare quality drops or fails, and this may ultimately determine whether NHI reforms succeed. The PCH cannot easily shift accountability and reporting lines from the MoH to Parliament, but could amend the Bill to devolve more power to the Fund, constrain the MoH's power and guide appointments, with minor wording changes to the Bill.

The contestation on constitutional grounds and human rights responsibilities revealed several legal shortcomings with the potential to halt or seriously delay the path to implementation. The PCH will need to consider whether these concerns carry a high risk of constitutional challenge and consequent delay. They could simply proceed without addressing these concerns, or amend the Bill to address or remove constitutionally problematic components to mitigate this risk.

A viable NHI financing model is critical to the success of the whole initiative, but no tangible evidence was presented to support the proposed shift from the current model to the proposed public-dominant funding model. The PCH will need to consider whether they can endorse the Bill in its current, potentially unaffordable form, or whether they will address this critical omission.

A high level of concern about corruption was expressed across all sectors, with several suggestions for its management. The PCH must consider whether the threats posed by corruption are of such a nature that NHI would be unable to deliver on its stated objectives. They will need to decide what safeguards are sufficient when corruption in SA as a whole is not contained.

Access and equity are the most prominent aspirational features of the Bill, so it is critical to ensure that it can deliver on these. The PCH heard how the Bill could profoundly limit access through administrative barriers and conflict with human rights legislation. The PCH has been challenged to ensure that the proposed rules on eligibility, registration, and referral pathways are viable and fair, a task complicated by the lobbying of special interest groups.

There is heightened public expectation that NHI will provide for all healthcare needs without financial difficulty. Potentially severe financial constraints will require NHI to carefully balance the types and comprehensiveness of the benefits it chooses to cover. The Bill lacks clarity on the benefits to be offered, but the PCH may have to leave the legislation open ended', as any benefits the Fund chooses to cover will be dependent on available funding and future circumstances. The case for amending the Bill to provide a clear process and principles to guide the NHI in determining benefits is strong - benefit determination is passionately contested terrain, so amending the Bill to provide clearer legislative guidelines will help the Fund navigate this terrain. The response of PCH members indicates recognition that the success of NHI is critically dependent on getting the benefits package right.

With its focus on personal clinical care, the Bill makes only rhetorical reference to comprehensive care, but several groups highlighted the exclusion of key public health measures required to ensure population health. This role is defined outside the brief of the Bill, a serious omission in the view of some respondents. To address this, the Bill would need to fundamentally expand its scope of responsibility or make it clear that the responsibility for this level of healthcare lies elsewhere.

The PCH review of the Bill is guided by the Constitution[27] and parliamentary rules.[103] In terms of Assembly Rules 267 - 268,[104] the PCH has three ways of dealing with the Bill. The PCH could pass the Bill with only minor or no amendments. This is likely to prompt constitutional court challenges, erode public support for NHI and weaken the healthcare system. The PCH could make substantive amendments to the Bill (confined to the subject of the Bill),[105] before another round of public consultation, or it could reject the Bill[106] if it considers the objections substantial.

As one of the largest reforms proposed since 1994, it would be prudent for the PCH to meaningfully address the concerns raised by respondents and sustain public support for the Bill, even if this delays its passing. The approach taken by the PCH will have a profound impact not only on SAs future health system but also on the broader trajectory of social, societal and economic wellbeing.[3]

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. Institutional support to the study authors provided by the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), the University of Cape Town and the Clinton Health Access Initiative is acknowledged.

Author contributions. Conceived and designed the study: GCS, VB. Developed the article: GCS, VB, NGM, SW. Reviewed the article: NGM, JEC.

Funding. GCS is employed on a contractual basis by the SAMRC and NMG Consultants and Actuaries; support in the form of salaries was provided by the SAMRC. VB is employed by the Clinton Health Access Initiative. None of these institutions had any additional role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest. GCS is employed on a contractual basis by NMG Consultants and Actuaries, an independent consulting firm providing consulting and actuarial services to South African private health insurance funds. VB is employed by the Clinton Health Access Initiative who consult to the Department of Health. Neither NMG nor the Clinton Health Access Initiative had any role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. As such, there were no conflicts of interest in the conduct of the study.

References

1. South Africa. National Health Insurance Bill [B 11-2019]. July 2019. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcisdocument/201908/national-health-insurance-bill-b-11-2019.pdf (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

2. Parliamentary Monitoring Group. Health. National Assembly Committee. https://pmg.org.za/committee/63/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

3. Solanki GC, Cornell JE, Morar RL, et al. The National Health Insurance Bill Responses and options for the Portfolio Committee on Health. S Afr Med J 2021;11(9):812-813. http://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2021.V11119.15926 [ Links ]

4. Solanki G, Cornell J, Wild S, Morar R, Brijlal V The role of the Minister of Health in the National Health Insurance Bill. Challenges and options for the Portfolio Committee on Health. S Afr Med J 2022;112(5):317-320. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2022.vll2i5.16414 [ Links ]

5. Solanki G, Cornell J, Morar R, Brijlal V. NHI Bill. Parliaments health committee faces range of options after 100,000-plus submissions received. Daily Maverick 8 September 2021. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-09-08-nhi-bill-parliaments-health-committee-faces-range-of-options-after-lOOOOO-plus-submissions-received/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

6. Solanki G, Wild S, Cornell J. Brijlal V. Mixed views and scepticism continue to obstruct pathway of NHI Bill. Daily Maverick, 1 March 2022. https://www.dailymaverickco.za/artide/2022-03-01-mixed-views-and-scepticism-continue-to-obstruct-pathway-of-nhi-bill/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

7. Solanki G, Myburgh N, Wild S, Cornell J, Brijlal V Health Bill (Part 1). Summary of views on the proposed health funding model presented to Parliament. Daily Maverick, 23 March 2022. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-03-23-a-summary-of-views-on-the-proposed-heaIth-funding-model-presented-to-parliament/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

8. Solanki G, Myburgh N, Wild S, Cornell J, Brijlal V. Health Bill (Part 2). NHI will stand or fall on Parliaments approach to corruption, say civil society bodies. Daily Maverick 3 April 2022. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-04-03-nhi-will-stand-or-fall-on-parliaments-approach-to-corruption-say-civil-society-bodies/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

9. Solanki G, Myburgh N, Wild S, Cornell J, Brijlal V. Health Bill (Part 3). Too much ministerial power for NHI - challenges and options for the portfolio committee. Daily Maverick 11 April 2022. https://www.dailymaverickco.za/article/2022-04-ll-too-much-ministerial-power-for-nhi-challenges-and-options-for-the-portfolio-committee/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

10. Solanki G, Myburgh N, Wild S, Cornell J, Brijlal V. Health Bill (Part 4). Hie controversial National Health Insurance Bill has serious constitutional and human rights implications. Daily Maverick 21 April 2022. https://www.dailymaverickco.za/article/2022-04-21-the-controversial-national-health-insurance-bill-has-serious-constitutional-and-human-rights-imphcations/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

11. Solanki G, Myburgh N, Wild S, Cornell J, Brijlal V. Health Bill (Part 5). Concern about healthcare access for refugees, rural children, injured employees, the elderly and those living with disabilities. Daily Maverick, 3 May 2022. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-05-03-concern-about-healthcare-access-for-refugees-rural-children-injured-employees-the-elderly-and-those-living-with-disabilities/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

12. Solanki G, Myburgh N, Wild S, Cornell J, Brijlal V. Health Bill (Part 6). The NHI will not succeed unless its benefits package is accepted across the broad spectrum of society. Daily Maverick 21 May 2022. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-05-12-the-nhi-will-not-succeed-unless-its-benefits-package-is-accepted-across-the-broad-spectrum-of-society/ (accessed 21 May 2022). [ Links ]

13. National Health Laboratory Services presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 3. 20 May 2021. https://pmgorg.za/committee-meeting/32994/ (accessed 20 May 2022). [ Links ]

14. SA Nursing Council presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 1. 18 May 2021. https://pmgorg.za/committee-meeting/32925/ (accessed 18 May 2022). [ Links ]

15. Free Market Foundation presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 10. 29 June 2021. https://pmg.orgza/committee-meeting/33258/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

16. FW de Klerk Foundation presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 17. 28 July 2021. https://pmg.orgza/committee-meeting/33324/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

17. Oticon presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 16. 27 July 2021. https://pmg.orgza/committee-meeting/33321/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

18. National Planning Commission presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 26. 9 February 2022. https://pmgorg.za/committee-meeting/34285/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

19. Board of Healthcare Funders presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 1. 18 May 2021. https://pmgorg.za/committee-meeting/32925/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

20. Khayelitsha and Klipfontein Health Forums presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 5. 1 June 2021. https://pmgorg.za/committee-meeting/33119/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

21. South African Human Rights Council presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 2. 19 May 2021. https://static.pmg.org.za/210519SAHRC_Submission.pdf (accessed 16 May 2022) [ Links ]

22. Public Health Association of South Africa presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 2. 19 May 2021. https://static.pmg.org.za/210519PHASA_Submission_on_NHI_BilLpdf (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

23. Cancer Association of South Africa submission to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill: public hearings day 7. 15 June 2021. https://staticpmg.org.za/210615CANSA_PRESENTATION_-_15_JUNE_2021.pdf (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

24. Duliah Omar Institute submission to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 7. 15 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33206/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

25. Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stelienbosch University submission to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 6.2 June 2021. https://static.pmg.org.za/210602NHI_Bill_Submission_SU_FMHS.pdf (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

26. Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University of Cape Town submission to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 6. 2 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33159/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

27. South Africa. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa. 10 December 1996. https://www.refworid.org/docid/3ae6b5de4.html (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

28. Department of National Health, South Africa. Policy on National Health Insurance (Green Paper). 12 August 2011. https://www.greengazette.co.za/documents/nationai-gazette-34523-of-12-august-2011-vol-554_20110812-GGN-34523.pdf(accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

29. Business Unity South Africa presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 10. 29 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33258/(accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

30. South Africa. Public Finance Management Act No 1 of 1999. http://www.treasury.gov.za/legislation/PFMA/actpdf (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

31. National Treasury. South Africa. Annual Report Guide for Schedule 3A and3C Public Entities, https://www.westerncape.gov.za/sites/www.westerncape.govza/fiies/public_entity_ar_guide.pdf (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

32. African National Congress presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 29. 23 February 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34403/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

33. Bonitas presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 22. 25 January 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34114/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

34. South African Medical Association presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 5. 1 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33119/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

35. Professional Provident Society presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 25. 8 February 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34280/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

36. Mediclinic presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 23. 26 January 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34132/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

37. Law Society of South Africa and Others v Minister for Transport and Another, ZACC 25 Case CCT 38/10. Sect. 21 (2010). [ Links ]

38. Chaoulli v. Quebec (Attorney General), 2005 SCC 35 (CanLII), [2005] 1 SCR 791. [ Links ]

39. Discovery Health presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHT, Bill, public hearings day 22. 25 January 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34114/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

40. South African Private Practitioner Forum presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 8. 22 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33227/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

41. South African Society of Physiotherapy presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 7. 15 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33206/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

42. Democratic Alliance presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 29. 23 February 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34403/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

43. South Africa. National Health Act 61 of 2003. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409M61-03.pdf (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

44. South African Local Government Association presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 23. 26 January 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34132/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

45. South African Medical Technology Industry Association presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 14. 20 July 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33306/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

46. University of the Witwatersrand presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 15. 21 July 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33309/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

47. MSD presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 13. 14 July 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33293/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

48. Scaiabrini Centre presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHTj Bill, public hearings day 26. 9 February 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34285/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

49. independent Community Pharmacy Association presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 17. 28 July 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33324/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

50. Lawyers for Human Rights presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 19. 10 September 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33613/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

51. Active Citizens Movement presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 19. 10 September 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33613/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

52. Childrens Health Institute, University of Cape Town presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 5. 1 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33119/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

53. Rural Rehab South Africa presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 7. 15 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33206/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

54. South African Committee of Medical Deans presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) BÜL public hearings day 28. 16 February 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34333/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

55. National Education, Health and Allied Workers' Union presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 28. 16 February 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34333/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

56. Congress of South African Trade Unions presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 27. 15 February 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34311/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

57. Alliance of South African Independent Practitioners Association presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 8. 22 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33227/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

58. GEMS (Government Employees Medical Scheme) presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 26. 9 February 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34285/(accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

59. Collaboration for Health Systems Analysis and Innovation presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 8. 22 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33227/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

60. AfriForum presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 27. 15 February 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34311/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

61. Counselling Psychology South Africa presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 8. 22 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33227/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

62. Section 27 and Treatment Action Campaign presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 20. 1 December 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33613/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

63. South African Dental Association presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 9. 23 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33238/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

64. Institute for Race Relations presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 8. 22 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33227 (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

65. Section 27 and Concentric Alliance presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 20. 1 December 2020. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33613/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

66. Peoples Health Movement presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 25. 8 February 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34280/(accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

67. Health Funders Association presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 13. 14 July 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33293/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

68. Helen Suzman Foundation presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 17. 28 July 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33324/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

69. SACP (South African Communist Party) presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 27.15 February 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34311/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

70. Psychology Society of South Africa presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 9. 23 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33238/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

71. Icon Oncology presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 10.29 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33258/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

72. South African Medical Research Council presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 3. 20 May 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/32994/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

73. Health Products Association of Southern Africa presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 11. 30 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33271/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

74. Momentum Health Solutions presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 13. 14 July 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33293/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

75. Public Service Accountability Monitor presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 21. 8 December 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34058/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

76. Hospital Association of South Africa presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 23. 26 January 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34132/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

77. National Health Care Professionals Association presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 4. 26 May 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33078/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

78. Black Business Council presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 19. 10 September 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33613/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

79. Western Cape Governmentpresentationto Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 23. 26 January 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34132/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

80. Federated Employers' Mutual Assurance Company presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 13. 14 July 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33293/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

81. Society of Private Nurse Practitioners of South Africa presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 14. 20 July 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33293/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

82. National Department of Health, South Africa. The Patients' Rights Charter. https://www.idealhealthfacility.org.za/App/Document/Download/150 (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

83. Genetic Alliance presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 25. 8 February 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34280/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

84. Commission for Gender Equality presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 24. 28 January 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34148/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

85. Educational Psychology Association presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 8. 22 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33238/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

86. South African Disability Alliance presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 21. 8 December 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34058/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

87. Council for Health Service Accreditation of Southern Africa presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 9. 23 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33238/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

88. Actuarial Society of South Africa presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 8. 22 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33238/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

89. Progressive Professionals Forum presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 9. 23 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33238/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

90. South African Association of Hospital and Institutional Pharmacies presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 4. 26 May 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33078/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

91. Polmed presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 22. 25 January 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34114/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

92. Pharmaceutical Task Group presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 12. 13 July 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33291/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

93. Ministerial Task Team on Social Health Insurance. Social health insurance options. Financial and fiscal impact assessment. Pretoria. National Department of Health, 2005. [ Links ]

94. Becton Dickinson presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 12. 13 July 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33291/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

95. J&J presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 14. 20 July 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33306/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

96. Sanofi presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 10.29 June 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33258/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

97. Systagenix presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 12. 13 July 2021. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/33291/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

98. South African Medical Research Council 2 presentation to Portfolio Committee on Health. National Health Insurance (NHI) Bill, public hearings day 26. 9 February 2022. https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/34285/ (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

99. Auditor-General of South Africa. Auditor-general reports an overall deterioration in the audit results of national and provincial government departments and their entities. Media release, 21 November 2018. https://www.agsa.co.za/Portals/0/Reports/PFMA/201718/MR/2018%20PFMA%20Media%20Release.pdf (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

100. The Judicial Commission of Inquiry into Allegations of State Capture, Corruption and Fraud in the Public Sector including the Organs of State (Zondo Commission). https://www.statecapture.org.za/ (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

101. Special Investigations Unit. Investigation of the National Department of Health/Digital Vibes (Pty) Ltd contracts. Proclamation No R. 23 of 2020. https://www.scribd.com/document/528274042/Presidential-Report-30-June-2021-Digital-Vibes-l#from_embed (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

102. World Health Organization. Universal health coverage (UHC). 1 April 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/universal-health-coverage-(uhc) (accessed 16 May 2022). [ Links ]

103. Parliament, South Africa. Joint Rules of Parliament. https://www.parlianient.gov.za/storage/app/media/JointRules/joint-rules-a51.pdf (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

104. Parliament, South Africa. The Rules of the National Assembly, 9th edition, chapter 13. https://static.pmg.org.za/160526NA_RULES_PDF_LAYOUT.pdf (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

105. Parliament, South Africa. The Rules of the National Assembly, 9th edition, section 332. https://static.pmg.org.za/160526NA_RULES_PDF_LAYOUT.pdf (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

106. Parliament, South Africa. The Rules of the National Assembly, 9th edition, section 288. https://static.pmg.org.za/160526NA_RULES_PDF_LAYOUT.pdf (accessed 17 May 2022). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

G C Solanki

geetesh.solanki@mrc.ac.za

Accepted 17 May 2022