Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.111 n.12 Pretoria Dec. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2021.v111i12.15841

RESEARCH

Retain rural doctors: Burnout, depression and anxiety in medical doctors working in rural KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa

S HainI; A TomitaII, III; P MilliganIV; B ChilizaV

IMB ChB, DMH (SA); Department of Psychiatry, School of Clinical Medicine, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IIPhD; KwaZulu-Natal Research Innovation and Sequencing Platform (KRISP), College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IIIPhD; Centre for Rural Health, School of Nursing and Public Health, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IVMB ChB, DCH (SA), DTM&H, DPH, FC Psych (SA); Department of Psychiatry, School of Clinical Medicine, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

VMB ChB, FC Psych (SA), PhD; Department of Psychiatry, School of Clinical Medicine, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: There is a need to retain medical doctors in rural areas to ensure equitable access to healthcare for rural communities. Burnout, depression and anxiety may contribute to difficulty in retaining doctors. Some studies have found high rates of these conditions in medical doctors in general, but there is little research available on their prevalence among those working in the rural areas of South Africa (SA

OBJECTIVES: To determine the prevalence of burnout, depression and anxiety in doctors working in rural district hospitals in northern KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) Province, SA, and to explore the associated sociodemographic and rural work-related factors

METHODS: We performed a quantitative descriptive cross-sectional study in three districts in northern KZN among medical doctors working at 15 rural district hospitals during August and September 2020. The prevalences of burnout, depression and anxiety were measured using the Maslach Burnout Inventory, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item questionnaire, respectively. The sociodemographic and rural occupational profiles were assessed using a questionnaire designed by the authors. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse the data

RESULTS: Of 96 doctors who participated in the study, 47.3% (n=44) were aged between 24 and 29 years and 70.8% (n=68) had worked in a rural setting for <5 years. Of the participants, 68.5% (n=61) were considered to have burnout. The screening tests for depression and anxiety were positive for 35.6% (n=31) and 23.3% (n=20) of participants, respectively. Burnout alone was significantly associated with female gender (84.8%; n=39) (x2=11.65, df=1, p=0.01). Burnout (x2=8.14, df=3, p=0.04) and anxiety (x2=12.96, df=3, p<0.01) were both significantly associated with occupational rank, with 85.2% (n=23) of community service medical officers (CSMOs) reporting the former and 29.6% (n=8) screening positive for generalised anxiety disorder. Burnout (x2=7.61, df=1, p=0.01), depression (x2=5.49, df=1, p=0.02) and anxiety (x2=4.08, df=1, p=0.04) were all shown to be significantly associated with doctors planning to leave the public sector in the next 2 years

CONCLUSIONS: Our study found high rates of burnout, depression and anxiety in rural doctors in northern KZN, all of which were associated with the intention to leave the public sector in the next 2 years. Of particular concern was that CSMOs as a group had high burnout and anxiety rates and female gender was associated with burnout. We recommend that evidence-based solutions are urgently implemented to prevent burnout and retain rural doctors

Some international and South African (SA) studies have found high rates of burnout,[1-10] depression[5,9,11-16] and anxiety[9,17] in medical doctors. SA studies have revealed burnout rates ranging from 59% to as high as 100%[5-7,9] and depression rates ranging from 21.3% to 40.7%,[5,9,16] and a recent study in eThekwini Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) Province, reported anxiety rates of 20% in doctors.[9]

With burnout becoming increasingly recognised as a problem in the medical profession, the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) has included it as an occupational phenomenon (not a medical condition).[18] Burnout has been described as 'a persistent, negative, work-related state of mind in "normal" individuals that is primarily characterised by exhaustion, and is accompanied by distress, a sense of reduced effectiveness, decreased motivation and the development of dysfunctional attitudes and behaviour at work'.[19] It has been shown to have profound personal and professional consequences that have influenced the recruitment and retention of doctors, as well as being detrimental to patient care and impacting on the functionality of healthcare systems.[2,6,20,21]

While burnout is a great public health concern in SA, there is very little research available on its prevalence (and the prevalence of depression and anxiety) among doctors working in the rural areas of the country. To our knowledge, there has only been one recent study investigating the prevalence of burnout in doctors working in rural areas in SA. This was conducted in 2013 among doctors working in the district health system in the Overberg and Cape Winelands districts of Western Cape Province, and found that 81% of them had clinically significant burnout.[22] Many factors may impact negatively on rural doctors and contribute to burnout. These include excessive workloads with substantial after-hours duties, inferior clinical equipment and facilities, lack of specialist back-up, a perceived lack of management support, inappropriate training for rural work, language barriers and lack of a defined career path. On a personal level, rural doctors report feelings of isolation, a lack of recreational facilities, poor housing, spouse dissatisfaction and limited schooling opportunities for their children.[23-26] Rural district hospitals are also mostly staffed by community service medical officers (CSMOs) and other junior doctors. While doctors of all ages and demographic profiles are prone to burnout, junior doctors are noted to be particularly vulnerable.[2,8,9,26] Schweitzer[26] found the rate of burnout among young doctors working in the SA district health service to be as high as 77.8%.

The distribution of doctors between urban and rural areas in SA is unequal.[27] In 2011, an editorial in the SAMJ[27] reported that 46% of SA's residents were served by only 12% of its doctors, mostly from the public sector. In response to this maldistribution of doctors, many ways have been used to attract doctors to work in rural areas, one being compulsory community service (CS), which doctors need to complete before they can be licensed as independent practitioners.[27] Reid et al.[28] tracked the experiences of these CSMOs each year from 2000 to 2014 and found that while CS has largely met its original objectives of redistribution of health professionals and promoting their professional development, only about half felt adequately supported clinically and administratively. The authors noted that the CS experience needed to be complemented by other interventions to capitalise on its potential, and that only 15% of CSMOs planned to work in rural or under-served areas after their year of CS.[28] While there is a need to attract doctors to rural district hospitals, there is also a need to retain them to ensure equitable access to healthcare for rural communities in SA. Burnout, depression and anxiety may contribute to the difficulty in retaining these rural doctors.

Objectives

To determine the prevalence of burnout, depression and anxiety in doctors working in rural district hospitals in northern KZN and to explore the associated sociodemographic and rural work-related factors.

Methods

We performed a quantitative descriptive cross-sectional study in three districts in northern KZN, namely the King Cetshwayo, Umkhanyakude and Zululand districts. These districts were chosen because they are supported by Ngwelezana Hospital, which is affiliated with the University of KwaZulu-Natal and has research-supporting infrastructure. All 16 rural district hospitals in the districts were invited to participate in the study, one of which declined, resulting in 15 participating institutions. The following hospitals were included: Catherine Booth, Ekombe, Eshowe, Mbongolwane, Nkandla, Bethesda, Hlabisa, Manguzi, Mosvold, Mseleni, Benedictine, Ceza, Itshelejuba, Nkonjeni and Vryheid.

The study included medical doctors who were working at these rural hospitals during August and September 2020, when data collection took place. A convenience sampling technique was used, and doctors were only excluded if they worked part-time or did not agree to participate in the study. The medical managers provided their doctors' email addresses, with some managers also providing their phone numbers. The doctors were e-mailed an invitation to participate in the study, with a link to the study questionnaire using SurveyMonkey. The invitation contained information about the study, the background and purpose, and instructions on how to complete the questionnaire. Follow-up emails and WhatsApp reminders were sent and phone calls made to the participants during the weeks that followed.

Participation in the study was entirely voluntary, and informed consent was obtained electronically for each participant before they could complete the questionnaire. Confidentiality of all participant information was protected by declaring no identifying data or hospital names on the questionnaires.

The initial email included mental health resources and contact details for the suicide crisis line, the South African Depression and Anxiety Group and the Department of Social Development substance abuse line. The authors' contact details, as well as those of the Ngwelezana Psychiatry Department and two private psychiatrists in the region, were made available for any participant should they require any assistance.

Four self-report questionnaires were used in the study: (i) a sociodemographic and occupational profile questionnaire designed by the authors, to assess sociodemographic and rural work-related factors; (ii) the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) Human Services Survey, to assess the prevalence of burnout; (iii) the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), to assess the prevalence of depressive symptoms; and (iv) the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item questionnaire (GAD-7), to assess the prevalence of anxiety symptoms. Variables obtained on the sociodemographic and occupational profile questionnaire consisted of the participant's age, gender, marital status, race, highest level of education, country of qualification and occupational rank, the years worked since qualification, years worked in a rural area, overtime hours, number of senior doctors working at their hospital, distance from immediate family and how often they saw their family, and their perception of staff turnover, cell phone signal, internet signal, and living quarters at their hospital. Participants were asked about their willingness to work where they currently were and whether they planned on leaving medicine and/ or the public sector and/or the rural sector within the next 2 years. Participants were also asked to choose the 6 most important factors that contributed to stress for them (from a list of 24 provided factors) and what in their opinion were the 3 most important factors that would prevent stress build-up for them (from a list of 14 provided factors).

In the MBI, Maslach et al.[29]recognise burnout as consisting of three components, namely emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonali-sation (DP) and reduced personal accomplishment (PA). EE refers to workers feeling that they can no longer give of themselves at a psychological level, while DP is a consequence of EE and refers to a callous or dehumanising perception of others. PA relates to perceived satisfaction with accomplishments at work.[29] The MBI contains 22 questions answered on a 7-point Lickert scale from 0 to 6 to measure the three components of burnout. High scores in EE or DP are considered to indicate clinically significant burnout, whereas the lower the score on the PA scale, the higher the degree of burnout.[29] Participants in the present study who had high scores in EE (>27) or DP (>10) were considered to have burnout, as these criteria have been suggested in the Maslach guidelines and have also been used in most studies including those in SA.[5,6,9,29] Each of the three components was considered separately, and a scoring key adjusted specifically for measuring burnout in medical human service occupations was used. The MBI has been found to be reliable, valid and easy to administer, and has demonstrated internal reliability (Cronbach's coefficient alpha 0.71 - 0.9).[29]

The PHQ-9 is used to screen for depression in primary care and other healthcare settings. It consists of 9 questions, answered on a 4-point scale from 0 to 3. Scores range from 0 to 27, with a score of >10 usually indicating the presence of a depressive disorder that would benefit from treatment.[30] In a recent SA study, the PHQ-9 showed high accuracy in correctly classifying cases of current major depressive episodes (area under the curve 0.88) relative to the reference standard Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI).[30]

The GAD-7 is a 7-item, self-rated scale developed as a screening tool for generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). It is answered on a 4-point scale from 0 to 3, and a cut-off score of 10 was identified as the optimal point for sensitivity (89%) and specificity (82%).[31] Validation of the GAD-7 in a large primary care sample revealed that the measure has good reliability, and good criterion, factorial and procedural validity.[311 This same scale and cut-off score was recently used in the study in eThekwini Municipality published in 2020.[9]

Statistical analysis

Four analyses were conducted for this study. First, we summarised the sociodemographic and occupational profile of participants using descriptive statistics. Second, we summarised the clinical profiles (e.g. burnout, depression and anxiety) from the MBI, PHQ-9 and GAD-7, using descriptive statistics. Third, we examined sociodemographic and occupational profile factors of burnout, depression and anxiety, with significant factors being identified based on x2 statistics. Lastly, we summarised perceived occupational factors of burnout using descriptive statistics. The level of significance was set at p<0.05, with the data analysed using Stata version 16 (StataCorp, USA).

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (BREC) of the University of KwaZulu-Natal (ref. no. BREC/0000/1095/2020), the KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health and the district managers of the respective districts. No financial remuneration was offered to the participants.

Results

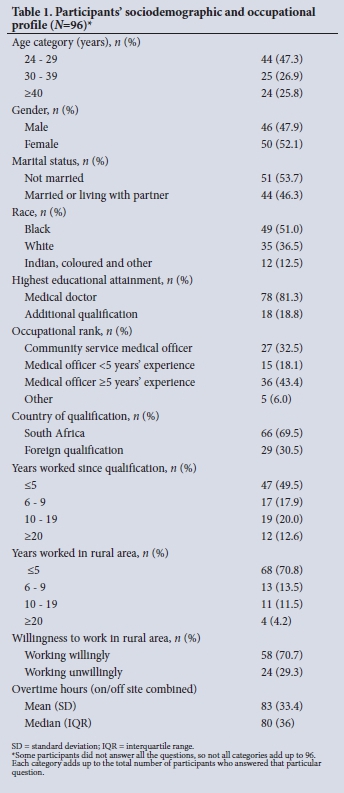

Sociodemographic and occupational profile (Table 1)

Of the 213 doctors who were invited to participate, 96 signed informed consent and completed the sociodemographic and occupational profile questionnaire. Of these, 89 completed the MBI, 87 the PHQ-9 and 86 the GAD-7. Of the sample, 47.3% (n=44) were aged 24 - 29 years, 52.1% (n=50) were female, 70.8% (n=68) had worked in a rural setting for <5 years, and 30.5% (n=29) had attained their medical qualifications outside SA.

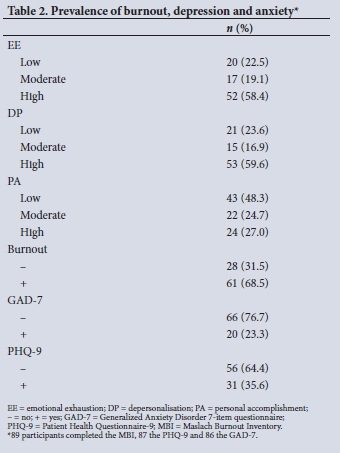

Prevalence of burnout, depression and anxiety (Table 2)

Of the 89 doctors who completed the MBI questionnaire, 68.5% (n=61) were assessed as having burnout (Table 2). The screening tests were positive for depression in 35.6% (n=31) of 87 respondents, and for anxiety in 23.3% (n=20) of 86 respondents.

Associations between burnout, depression and anxiety and sociodemographic and occupational profile variables (Table 3)

Burnout alone was significantly associated with gender (x2=11.65, df=1, p=0.01), with 84.8% (n=39) of females having high scores in EE or DP. Burnout (x2=8.14, df=3, p=0.04) and anxiety (x2=12.96, df=3, p<0.01) were both significantly associated with occupational rank, with 85.2% (n=23) of CSMOs reporting burnout and 29.6% (n=8) screening positive for GAD. Burnout (x2=7.61, df=1, p=0.01), depression (x2=5.49, df=1, p=0.02) and anxiety (x2=4.08, df=1, p=0.04) were all shown to be significantly associated with doctors planning on leaving the public sector within the next 2 years.

Anxiety was associated with unwillingness to work in a rural setting (x2=4.79, df=1, p=0.03), and both anxiety (x2=4.64, df=1, p=0.03) and depression (x2=10.68, df=1, p=0.01) were associated with country of qualification, with SA-qualified doctors reporting higher rates.

There were no significant associations between occupational rank and the individual components of burnout (EE, DP and PA) (Table 4).

Stress in rural doctors: Perception of contributory and preventive factors

The 7 most important factors reported by the participants as contributing to stress were difficulty referring patients (n=58), staff shortages (n=41), lack of equipment (n=41), lack of management support (n=39), balancing work and personal life (n=35), difficulty with language/culture (n=30) and lack of specialist back-up support (n=30).

When asked about the 3 most important factors that would prevent stress build-up for them, the participants reported improving recruitment (n=36), management skills/systems (n=32) and staff relationships (n=27). Three-quarters (75%; n=57) of participants reported that an independent service provider unaffiliated to their hospital would be their preferred source of support for burnout, depression or anxiety.

Discussion

The study found high rates of burnout, depression and anxiety in medical doctors working in rural district hospitals in northern KZN. Two-thirds (68.5%) reported burnout (high scores in EE or DP components), which is similar to other SA studies.[5,7,8] However, this rate is notably higher than the 59% reported in the urban eThekwini study conducted in the same province and published in 2020.[9] This difference may be explained by our study participants consisting of more junior doctors and our sample size being smaller, and data collection taking place during August and September 2020, which coincided with the end of the COVID-19 first wave in SA. Although the study was done at the end of the first wave, the doctors' responses may have been influenced by their recent experiences of COVID-19 cases. As of 2 October 2020, there were relatively few confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the rural King Cetshwayo (n=10 202), Umkhanyakude (n=2 628) and Zululand districts (n=4 864). Of KZN's 11 health districts, the above three collectively accounted for 14.8% of the province's 119 212 confirmed cases.[32]

The 68.5% burnout rate in our study is lower than that in the Western Cape rural study, which reported a 81% rate in 2013 using the same MBI tool.[22] However, it should be noted that the Western Cape study sample size was much smaller, consisting of only 36 participants from two districts. Both SA rural studies reported significantly higher rates of burnout than rural studies elsewhere in the world.[33,34]

Over half (58.5%) of the doctors in the present study had high scores for EE, indicating that they felt that they could no longer give of themselves at a psychological level at work. A similar proportion (59.6%) had high scores for DP, reflecting a callous or dehumanising perception of their patients, and 48.3% had low scores in PA, reflecting that they felt unhappy with themselves and were dissatisfied with their job accomplishments. High rates of all three components of burnout in these doctors is of concern, as it is likely to affect the quality of care that they are able to provide their patients with. The relatively high rate of low PA may result from the frustrations that come from working in under-resourced rural district hospitals and the relative inability to change these conditions. In all three components of burnout, the rural doctors scored higher than their urban eThekwini colleagues.[9]

A key finding in this study was the very high rate of burnout in CSMOs compared with their more experienced colleagues. This young cadre had an extremely high burnout rate of 85.2% as a group, which is very concerning, given that these doctors are only beginning their careers. This finding is consistent with other literature, which reports junior doctors as being at higher risk of burnout than their more senior colleagues.[2,8,9,26] Although not statistically significant, 81.5% of CSMOs in the present study had high scores for DP compared with the older doctors (p=0.06): medical officers with <5 and >5 years' experience had 53.3% and 47.2% scores for DP, respectively. It is again concerning that such a high proportion of these young doctors may have a callous attitude towards their patients at such an early point in their career. This finding correlates with a study on medical doctors working in the Cape Town Metropolitan Municipality in community healthcare clinics and district hospitals, which found CSMOs as a group to have a significantly higher score on the DP subscale than respondents in other job categories.[5]

Another key finding in the present study was that gender was significantly associated with burnout, with 84.8% of females reporting burnout compared with 51.2% of males. There seems to be conflicting evidence in the literature regarding the association of gender with burnout, with most international reports indicating that there is a greater prevalence of burnout in female doctors,[35] and one large European study reporting that males were more prone than females.[2] A systematic review of burnout among healthcare workers in sub-Saharan Africa found it to be more common in women.[10] This of concern given the current feminisation of medicine, with an increase in the proportions of young female doctors qualifying.[36,37]

In the present study, not only did the CSMOs report the highest rates of burnout, but they also had statistically significant high anxiety rates as a group compared with their senior colleagues. The study found a rate of anxiety of 23.3% among all the doctors, which is similar to the finding of the urban eThekwini study.[9] However, the CSMOs were found to have the highest rate of anxiety at 29.6%, which may be due to their having to manage very stressful situations in rural hospitals with relatively little senior support. The urban eThekwini study did not find any correlation between anxiety and occupational rank, but rather with older age.[9] Our study also found higher anxiety rates among doctors who had not wanted to work in rural areas compared with doctors who were there willingly.

The study found a high rate of depression in the rural doctors (35.6%), which is in keeping with the Western Cape studies,[5,16] although different screening tools were used, which makes comparison a challenge. The rates are, however, significantly higher than in the urban eThekwini study, which used the same PHQ-9 screening tool and reported a 21.3% depression rate.[9] In our study, depression and anxiety were significantly associated with country of qualification, with SA-qualified doctors having higher rates of depression (46.6%) and anxiety (28.8%) compared with their colleagues who had qualified elsewhere (10.7% and 7.7%, respectively).

We argue that it is important not only to attract doctors to work in rural areas (through initiatives such as CS) but to retain their services in these under-served communities. The present study shows that doctors' experience in rural hospitals is not only associated with burnout, depression and anxiety, but that these were all significantly associated with the intention to leave the public sector within the next 2 years. However, a causal relationship between burnout, depression and anxiety and doctors' intention to leave the public sector has not been established, and further studies are required to determine a causal link if it exists.

Study limitations

Owing to the cross-sectional nature of the study design, causality could not be determined. Selection bias may also have been introduced by the convenience sampling technique that was used, and information bias by the use of self-report questionnaires. The response rate of 45% was low, despite frequent follow-up attempts, and may be accounted for in part by: (i) the online nature of the questionnaires; (ii) the requirement of internet access (which is difficult in many rural areas); and (iii) a fair degree of computer literacy being required to complete the questionnaires. A further limitation of the study was that we did not know the COVID-19 experience of each of the hospitals in terms of the status of their facilities and availability of personal protective equipment during the time of data collection, and how this may have contributed to the participants' state of mind. The study was conducted in rural district hospitals in northern KZN, and these findings may not be generalisable to rural district hospitals in other parts of the province or of SA.

Conclusions

There is a need to attract medical doctors to rural district hospitals and retain them there, to ensure equitable access to healthcare for rural communities in SA. The present study found high rates of burnout, depression and anxiety in rural doctors in northern KZN, all of which were associated with the intention to leave the public sector in the next 2 years. Of particular concern was that CSMOs as a group had high burnout and anxiety rates, and female gender was associated with burnout. We recommend that further studies be conducted in other rural areas in SA to investigate the prevalence of burnout, depression and anxiety and their impact on staff retention and patient care. Research is needed to establish whether the prevention and management of burnout, depression and anxiety would result in more doctors remaining in rural areas. We further recommend that both evidence-based organisational and individual-focused solutions be urgently explored and implemented to prevent burnout, with special consideration being given to CSMOs and female doctors in rural hospitals as part of the effort to retain rural doctors in our country's health system.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. We thank all the rural doctors who participated in this study. We also thank Drs T Naidoo and S Paruk for their helpful suggestions and contributions to the conceptualisation of this project.

Author contributions. Conceptualisation: SH, PM, BC. Formal analysis: AT. Methodology: SH, PM. BC. Project administration: SH. Supervision: PM, BC.

Writing, original draft: SH, AT, PM, BC. Writing, review and editing: SH, AT, PM, BC.

Funding. This work is based on research supported in part by the National Research Foundation of South Africa (grant no. RA 171218294830)

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med 2012;172(18):1377-1385. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199 [ Links ]

2. Soler JK, Yaman H, Esteva M, et al. Burnout in European family doctors: The EGPRN study. Fam Pract 2008;25(4):245-265. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmn038 [ Links ]

3. Prins JT, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, Tubben BJ, et al. Burnout in medical residents: A review. Med Educ 2007;41(8):788-800. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02797.x [ Links ]

4. Al-Dubai SAR, Rampal KG. Prevalence and associated factors of burnout among doctors in Yemen. J Occup Health 2010;52(1):58-65 https://doi.org/10.1539/joh.o8030 [ Links ]

5. Rossouw L, Seedat S, Emsley RA, Suliman S, Hagemeister D. The prevalence of burnout and depression in medical doctors working in the Cape Town Metropolitan Municipality community healthcare clinics and district hospitals of the Provincial Government of the Western Cape: A cross-sectional study. S Afr Fam Pract 2013;55(6):567-573. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786204.2013.10874418 [ Links ]

6. Stodel J, Stewart-Smith A. The influence of burnout on skills retention of junior doctors at Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital: A case study. S Afr Med J 2011;101(2):115-118. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.4431 [ Links ]

7. Zeijlemaker C, Moosa S. The prevalence of burnout among registrars in the School of Clinical Medicine at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. S Afr Med J 2019;109(9):668-672. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2019.v109i9.13667 [ Links ]

8. Peltzer K, Mashego T-A, Mabeba M. Occupational stress and burnout among South African medical practitioners. Stress Health 2003;19(5):275-280. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.982 [ Links ]

9. Naidoo T, Tomita A, Paruk S. Burnout, anxiety and depression risk in medical doctors working in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa: Evidence from a multi-site study of resource-constrained government hospitals in a generalised HIV epidemic setting. PLoS ONE 2020;15(10):e0239753. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239753 [ Links ]

10. Dubale BW, Friedman LE, Chemali Z, et al. Systematic review of burnout among healthcare providers in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Public Health 2019;19(1):1247. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7566-7 [ Links ]

11. Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2015;314(22):2373-2383. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.15845 [ Links ]

12. Mata DA, Ramos MA, Kim MM, Guille C, Sen S. In their own words: An analysis of the experiences of medical interns participating in a prospective cohort study of depression. Acad Med 2016;91(9):1244-1250. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000001227 [ Links ]

13. Ogawa R, Seo E, Maeno T, Ito M, Sanuki M, Maeno T. The relationship between long working hours and depression among first-year residents in Japan. BMC Med Educ 2018;18(1):50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-018-1171-9 [ Links ]

14. Sen S, Kranzler HR, Krystal JH, et al. A prospective cohort study investigating factors associated with depression during medical internship. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67(6):557-565. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.41 [ Links ]

15. Shen L-L, Lao L-M, Jiang S-F, et al. A survey of anxiety and depression symptoms among primary-care physicians in China. Int J Psychiatry Med 2012;44(3):257-270. https://doi.org/10.2190/pm.44.3.f [ Links ]

16. Naidu K, Torline JR, Henry M, Thornton HB. Depressive symptoms and associated factors in medical interns at a tertiary hospital. S Afr J Psychiatry 2019;25(0):a1322. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v25i0.1322 [ Links ]

17. Atif K, Khan HU, Ullah MZ, Shah FS, Latif A. Prevalence of anxiety and depression among doctors; the unscreened and undiagnosed clientele in Lahore, Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci 2016;32(2):294-298. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.322.8731 [ Links ]

18. World Health Organization. News. Burn-out an 'occupational phenomenon': International Classification of Diseases. 28 May 2019. https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases (accessed 20 November 2019). [ Links ]

19. Weinberg A, Creed F. Stress and psychiatric disorder in healthcare professionals and hospital staff. Lancet 2000;355(9203):533-537. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(99)07366-3 [ Links ]

20. Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med 2002;136(5):358-367. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008 [ Links ]

21. Salyers MP, Bonfils KA, Luther L, et al. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: A meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32(4):475-482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3886-9 [ Links ]

22. Liebenberg AR, Coetzee JF jr, Conradie HH, Coetzee JF. Burnout among rural hospital doctors in the Western Cape: Comparison with previous South African studies. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med 2018;10(1):1-7. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v10i1.1568 [ Links ]

23. Cameron D, Blitz J, Durrheim D. Teaching young docs old tricks: Was Aristotle right? An assessment of the skills training needs and transformation of interns and community service doctors working at a district hospital. S Afr Med J 2002;92(4):276-278. [ Links ]

24. De Villiers MR, de Villiers PJT. Doctors' views of working conditions in rural hospitals in the Western Cape. S Afr Fam Pract 2004;46(3):21-26. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786204.2004.10873056 [ Links ]

25. Sankar U, Jinabhai CC, Munro GD. Health personnel needs and attitudes to rural in KwaZulu-Natal. S Afr Med J 1997;87(3):293-298. [ Links ]

26. Schweitzer B. Stress and burnout in junior doctors. S Afr Med J 1994;84(6):352-354. [ Links ]

27. Reid S, Burch V. Fit for purpose? The appropriate education of health professionals in South Africa. S Afr Med J 2011;10(1):25-26. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.4695 [ Links ]

28. Reid SJ, Peacocke J, Kornik S, Wolvaardt G. Compulsory community service for doctors in South Africa: A 15-year review. S Afr Med J 2018;108(9):741-747. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2018.v108i9.13070 [ Links ]

29. Maslach C, Jackson S, Leiter M, Schaufeli W, Schwab R. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto, Calif.: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1996. [ Links ]

30. Cholera R, Gaynes BN, Pence BW, et al. Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in a high-HIV burden primary healthcare clinic in Johannesburg, South Africa. J Affect Disord 2014;167:160-166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.06.003 [ Links ]

31. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalised anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166(10):1092-1097. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [ Links ]

32. KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. Health Bulletin 28 Sept - 02 Oct 2020. http://www.kznhealth.gov.za/comms/HealthBulletin/28-2October-2020.pdf (accessed 4 May 2021). [ Links ]

33. Saijo Y, Yoshioka E, Hanley SJB, Kitaoka K, Yoshida T. Job stress factors affect workplace resignation and burnout among Japanese rural physicians. Tohoku J Exp Med 2018;245(3):167-177. https://doi.org/10.1620/tjem.245.167 [ Links ]

34. Zhao X, Liu S, Chen Y, Zhang Q, Wang Y. Influential factors of burnout among village doctors in China: A cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(4):2013. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18042013 [ Links ]

35. Amoafo E, Hanbali N, Patel A, Singh P. What are the significant factors associated with burnout in doctors? Occup Med 2014;65(2):117-121. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqu144 [ Links ]

36. Laurence D, Görlich Y, Simmenroth A. How do applicants, students and physicians think about the feminisation of medicine? - a questionnaire-survey. BMC Med Educ 2020;20(1):48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-1959-2 [ Links ]

37. Ncayiyana DJ. Feminisation of the South African medical profession - not yet nirvana for gender equity. S Afr Med J 2011;101(1):5. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.4705 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

S Hain

shaunhain@gmail.com

Accepted 12 August 2021