Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.111 n.6 Pretoria Jun. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2021.v111i6.15633

IN PRACTICE

HEALTHCARE DELIVERY

Strengthening of district mental health services in Gauteng Province, South Africa

L J RobertsonI, II; M Y H MoosaI, III; F Y JeenahI, IV

IMB BCh MMed (Psych); Department of Psychiatry, School of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIMB BCh MMed (Psych); Community Psychiatry, Sedibeng District Health Services, Gauteng Province, South Africa

IIIMB ChB MMed (Psych); Community Psychiatry, City ofJohannesburg, South Africa

IVMB ChB MMed (Psych) Department of Psychiatry, Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

In response to the Life Esidimeni tragedy, the Gauteng Department of Health established a task team to advise on the implementation of the Health Ombud's recommendations and to develop a mental health recovery plan. Consistent with international human rights and South African legislation and policy, the plan focused on making mental healthcare more accessible, incorporating a strategy to strengthen district mental health services to deliver community-based care for people with any type and severity of mental illness. The strategy included an organogram with three new human resource teams integrated into the district health system: a district specialist mental health team to develop a public mental health approach, a clinical community psychiatry team for service delivery, and a team to support non-governmental organisation governance. This article discusses the strategy in terms of guiding policies and legislation, the roles and responsibilities of the various teams in the proposed organogram, and its sustainability.

The Gauteng Department of Health (GDoH) has long grappled with the provision of rights-based, efficient mental health services. The 1991 United Nations Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illness and the Improvement of Mental Health Care ('the 1991 UN principles')[1] stated that people with mental illness 'shall have the right to be treated and cared for, as far as possible, in the community in which he or she lives ... [and] ... to receive such health and social care as is appropriate to his or her health needs, . in accordance with the same standards as other ill persons.'

The principles of community mental healthcare, aimed at reducing custodial care and institutionalisation, were embraced by South Africa (SA) in the 1997 White Paper for the transformation of the health system.[2] Community mental health services involve mental health promotion, de-stigmatisation, prevention of mental illness, and a person-centred, recovery-orientated therapeutic approach that fosters integrated mental and physical health care.[3] In providing various aspects of care, these services incorporate the community, including the non-health government sector (such as the departments of Social Development, Education, Housing, Labour, Justice and Correctional Services), non-governmental organisations (NGOs), traditional and faith healers, families and lay society. They therefore facilitate social inclusion as well as mental and physical healthcare for people with mental illness.

Accordingly, the GDoH began a process of deinstitutionalisation in the 1990s.[41 Funding from the closure of institutions was to 'follow the patient' to the district and community. Community psychiatry (with multidisciplinary specialist teams operating in the primary healthcare (PHC) setting, funded by the PHC mental health programme) and NGO residential and day-care centres were therefore established.[4] The community psychiatry services in southern Gauteng Province, supported by the Department of Psychiatry at the University of the Witwatersrand, expanded over the following two decades.[5,6]

However, human resource allocation was not sustained, possibly related to PHC re-engineering and integration of the mental health programme such that community mental healthcare would be provided by PHC practitioners. Nevertheless, deinstitutionalisation continued, culminating in the events of 2015 and 2016 known as the 'Life Esidimeni tragedy'

Recommendations and recovery plan

The Life Esidimeni tragedy led to a series of recommendations regarding human rights and healthcare of people with mental illness in SA,[7-9] with particular recommendations for the GDoH (Box 1). In May 2018, the GDoH convened a task team to advise on implementing the Health Ombud's recommendations and to develop a recovery plan. The team was later formalised as the Mental Health Technical Advisory Committee (MHTAC), a subcommittee of the GDoH Executive Management Committee.[10]

A recovery plan drafted by the MHTAC, the Gauteng Province Mental Health Strategy and Action Plan 2019 - 2023 (available from the corresponding author LJR at lesley.robertson@wits.ac.za) was approved on 3 May 2019 by the then Minister of the Executive Committee for Health, Dr Gwen Ramokgopa, and the Head of Department, Prof. Mkhululi Lukhele. Taking cognisance of the Health Ombud's recommendations, the recovery plan included the strengthening of district mental health services as a priority objective. In this article, we discuss selected policies and legislation that guide community mental health service development, the strategy that the MHTAC developed to realise such services in terms of the proposed organogram, and, finally, sustainability of the strategy.

Applicable policy and legislation

The MHTAC's strategy to strengthen district mental health services is aligned with the 1991 UN principles,[1] the SA Mental Health Care Act No.17 of 2002 (MHCA),[10] the World Health Organization (WHO)'s optimal mix of mental healthcare services,[11] and the SA National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan 2013 -2020 (NMHPF).[121 The WHO advocates for community-based, comprehensive, integrated mental healthcare and social services. Likewise, the NMHPF states that 'community mental health services will be scaled up to match recommended national norms' and 'the district mental health system will be strengthened' (p. 23).[12]

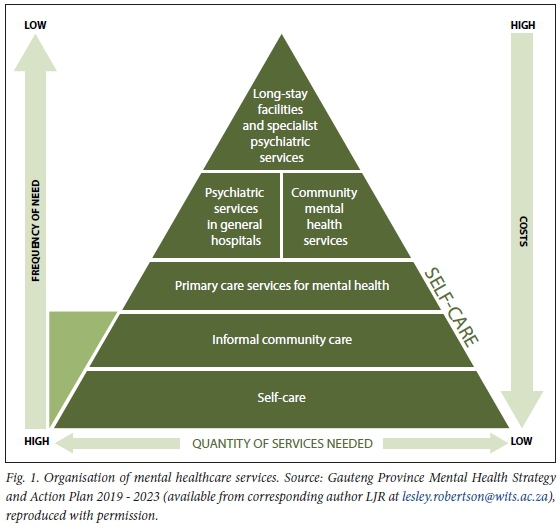

The service organisation used in the recovery plan (Fig. 1) is the same as that proposed by the WHO[11] and the NMHPF[12] District mental health services encompass community mental health services and primary care services for mental health, augmented by informal community care and self-care.

Community mental health services, operating back-to-back with psychiatric services in general hospitals, include residential and day-care and outpatient mental healthcare[12] While national norms for community-based mental healthcare have previously been developed,[13] national policy guidelines for the licensing of residential and/or day-care centres were gazetted by the National Department of Health (NDoH) in March 2018[14] in response to the Health Ombud's recommendation to the National Minister of Health (recommendation 18 of the 'Report into the circumstances surrounding the deaths of mentally ill patients: Gauteng Province').[17]

Primary care services for mental health are provided for in the Integrated Clinical Services Management manual,[15] which integrates mental health into PHC facility services in the 'chronic care' stream, and, by default, the 'acute episodic' service stream for people arriving without appointments or as emergencies. While the manual also describes mental health support teams (comprising a psychiatrist, a psychologist and a mental health nurse), it notes that these are not available in most of SA. Where they exist, they function with scheduled appointments, designated waiting areas, and bidirectional referral within the PHC facility. Mental health is not mentioned specifically in the manual regarding other components of a district health system, including ward-based PHC outreach teams, school health, NGOs, social services, environmental health, contracted service providers and district clinical specialist teams. However, it is included in many individual programme policy documents, and is implied in that it is a PHC facility service and population need.

Implementation of integrated community and PHC mental healthcare is not simple[3,11] Integrated care for people with severe mental illness, who are also likely to have physical health comorbidities and social deprivation, is particularly complex.[16] Nevertheless, mortality data and other syndemic research reveal an increasingly urgent need for such integration. Hence it is a fundamental part of the strategy developed by the MHTAC.

UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

The UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD),[17] ratified by SA in 2007, supersedes previous human rights instruments including the 1991 UN principles. Formed in response to persistent social exclusion and impoverishment of people with disabilities, the CRPD has far-reaching implications for mental health services. Importantly, society must accommodate the person with a disability, including those with mental, intellectual and/or other psychosocial disabilities, 'to promote, protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by all persons with disabilities, and to promote respect for their inherent dignity' (Article 1).

The mental health system must therefore accommodate the person in need, enabling service utilisation and observing their right to receive quality healthcare in equity with others. Additionally, the therapeutic goal becomes their 'full and effective participation and inclusion in society' (Article 3). Furthermore, equal recognition before the law' (Article 12) means that autonomy may not be compromised, as legal capacity is distinct from mental capacity.[18] Article 12 differs markedly from the 1991 UN principles and the SA MHCA, which allow substitute decision-making in the presence of mental incapacity to facilitate hospital admission and access to mental healthcare.

Observance of the CRPD, in particular of Article 12, requires a fundamental shift in the way mental health services are provided.[19] Accessible preventive care that aims to optimise wellness should be the mainstay of care, supported by hospitalisation when needed and before behaviour is severely disturbed. The MHTAC's strategy to strengthen district mental health services aims to uphold and deliver on the rights of people with mental illness and correlates with the South African Human Rights Commission recommendations on mental health care in the country.

Strategy to strengthen district mental health services

An organisational structure that endeavours to provide comprehensive community mental health services and integrates mental health professionals into the current district health system was drafted and costed by the MHTAC (Fig. 2). While the new human resource posts have been approved and are in the process of being filled, the proposed organogram is still to be officially endorsed and reporting to higher-level management finalised.

The MHTAC advised that three district- based human resource teams be created: clinical community psychiatric teams (CCPTs), NGO governance and compliance teams (NGCTs) and district specialist mental health teams (DSMHTs) (Fig. 2). These teams are to work with the entire district health system and the local community.

Clinical community psychiatric teams (CCPTs)

A component of community mental health services, the CCPTs are to provide ambulatory, biopsychosocial, preventive psychiatric care to community-dwelling people with severe mental illness. The CCPTs build upon the community psychiatry teams begun in the 1990s and may be likened to the integrated clinical service management mental health support teams. In naming the CCPTs, the MHTAC used the term 'psychiatric' rather than 'mental health' to distinguish their scope of practice from that of PHC, NGOs and lay people. They are denoted as clinical' to discriminate between their service delivery role and the predominantly public health role of the DSMHTs.

The multidisciplinary staffing of the CCPTs is informed by Lund and Flisher's[13] model for community mental health, which is referenced on p. 23 of the NMHPF[12] as recommended national norms to which community mental health services should be scaled up. The human resource modelling aims to achieve mental healthcare coverage of 30% for common mental disorders and 50% for severe disorders. However, such coverage will only be achieved using a task-sharing approach involving all healthcare services and the non-health sector.[3,12,16] The CCPTs will thereforeprovide ongoing support to PHC, NGOs and other sectors, as well as individual patient care.

NGO governance and compliance teams (NGCTs)

NGO residential and day-care services (the other component of the community mental health services) were developed in Gauteng to support deinstitutionalisation and provide housing, food, and informal psychosocial rehabilitation.[4] However, excessive mortality occurred at certain, mostly newly formed, NGOs during the Life Esidimeni tragedy.[20] The Health Ombud's investigation[7] and the Arbitration hearings[8] exposed shockingly inept, sometimes fraudulent, NGO governance. Nevertheless, the GDoH is dependent upon NGOs to avoid homelessness and re-institutionalisation.

The NGCTs were formed in response to the NDoH guidelines gazetted in March 2018.[14] Their immediate role is to manage licensing requirements, ensure that users have access to quality mental and general healthcare, and provide ongoing training and support to NGO personnel, who are predominantly lay caregivers. Long-term strategies include engagement with civil society to expand the range and number of services according to population need.

District specialist mental health teams (DSMHTs)

The DSMHTs are senior multidisciplinary teams with specific terms of reference in the NMHPE Clinical duties comprise only a small proportion of their responsibilities. Using a public health approach, they are to conduct a situation analysis of the district population and develop an operational plan for mental health promotion and quality mental healthcare services within a recovery-orientated preventive framework. The full range of mental health disturbance is to be addressed, from nonspecific psychological distress and commonly occurring anxiety and depressive symptoms to severe affective and psychotic disorders, including neurodevelopmental and neurocognitive conditions as well as personality and substance use disorders. Therefore, DSMHTs are to develop integrated PHC and specialist-level mental healthcare services, strengthen referral pathways, and establish intersectoral liaison according to the roles and responsibilities outlined in the NMHPE

Intersectoral collaboration is necessary to strengthen population resilience and to promote mental health, for primary prevention of incident mental illness, early detection and referral in secondary prevention, and to mitigate psychosocial disability in tertiary prevention.[21] The DSMHTs will therefore provide ongoing outreach education and specialist input to non-health government programmes, civil society, and user-led initiatives to reduce determinants of poor mental health, untreated mental illness, exploitation and abuse.

Within the healthcare platform, all health staff working in general health settings will receive mental health training and ongoing routine supervision and mentoring to support integrated mental healthcare and basic psychosocial interventions focused on prevention of relapse, disability and premature mortality. Suicide prevention strategies and mental health screening, detection and referral in PHC and the school health programme are to be strengthened. Implementation of the NDoH Standard Treatment Guidelines and Essential Medicines List by PHC and the CCPTs is to be facilitated, monitored and evaluated. Quality improvement initiatives for mental health will be aligned with quality initiatives of the GDoH and the NDoH. Additional health indicators and local surveys may be implemented, together with a mental health research agenda based on identified priorities in each district.

Sustainability of the strategy

The MHTAC's strategy to strengthen district mental health services has strong social sustainability. However, the 2019 National Health Insurance Bill[22] does not make provision for specialist care in the district setting and may preclude future employment of the DSMHTs and CCPTs. A submission requesting specific changes to selected clauses to allow for district-based employment of specialists was made to the Parliamentary Portfolio Committee on Health by the South African National Mental Health Alliance Partnership in November 2019 (supplementary file, Mental Health Alliance submission on the National Health Insurance Bill, 27 November 2019, available at http://samj.org.za/public/sup/15633.pdf). It is therefore hoped that public mental health and community psychiatry will be accommodated by National Health Insurance, at least as an option for individual districts or provinces.

Notwithstanding its social sustainability, the strategy must be economically sustainable and therefore affordable and cost-effective. Inherent constraints regarding preventive mental healthcare, which may limit the capacity of the strategy to deliver, also require consideration.

Aifordability and cost-effectiveness

The CCPTs, NGCTs and DSMHTs may appear unaffordable for SA.

While the MHCA promotes community-based mental healthcare (section 4(b)),[10] it stipulates that services are made 'available to the population ... within the limits of available resources' (section 3(a)(i)). Notably, the human resource modelling conducted to support the MHCA, and used by MHTAC, has not previously been implemented,[23] possibly for financial reasons. However, any cost savings have not resulted in rights-based, efficient mental healthcare in SA. As the NMHPF states, rapid deinstitutionalisation in SA 'without the necessary development of community-based services . has led to a high number of homeless mentally ill, people living with mental illness in prisons and revolving door patterns of care' (p. 16).[12]

A national costing report on mental healthcare in 2016/17[24] revealed gross inefficiencies in returns on expenditure, including an estimated treatment gap of 90%. GDoH expenditure was more than adequate by WHO standards at ZAR2 334 million (6.2% of its total health budget), with an additional ZAR186 million on NGO subsidies (catering for 5 230 users) and an unreported amount on contracted long-stay institutional care. Almost half (49.4%) of expenditure went on three specialised psychiatric institutions, 8.5% was on mental healthcare in the PHC setting (including the community psychiatry services initiated in the 1990s), and the remainder was on specialised rehabilitation centres and general hospital psychiatric units. Notably, psychiatric readmissions within 3 months of discharge cost 24.2% of mental healthcare expenditure. Current spending is therefore not preventing relapse or achieving mental health coverage, and appears unsustainable.

It is hoped that expenditure on strengthening district mental healthcare services will yield positive results. Anticipated outcomes include, at macro level, greater population coverage and reduced suicide rates and premature mortality, although mortality, being caused most often by medical or surgical conditions,[18] may be difficult to gauge. At meso level, reductions in readmission rates, emergency room attendance, and psychiatric institution beds are hoped for. Micro-level outcomes include improved user satisfaction, quality of life, and social and occupational functioning.

Preventive mental healthcare

Successful preventive mental healthcare depends on positive intersectoral collaboration and community care. It is unknown whether this will occur to the extent needed for the desired mental healthcare outcomes. In particular, high levels of trauma and unabated access to recreational substances could jeopardise all healthcare system efforts at preventive care.

The chronic, relapsing course of severe mental disorders means that hospitalisation, sometimes involuntary, will still be required[13]at least until we have stronger scientific evidence to inform effective preventive care for these conditions. A balanced allocation of resources between district services and general hospitals is therefore recommended. In Gauteng, regional hospital psychiatric wards are still poorly resourced.[16,24] To ensure the viability of district mental healthcare, advice and costing on staffing of general hospital psychiatric wards are included in the recovery plan. Nevertheless, the DSMHTs are key to ensure person-centred continuity of care between hospital and community and to generate evidence regarding effective preventive services for future generations.

Conclusions

In response to the Life Esidimeni tragedy, the related recommendations, and ongoing population need, the GDoH has acted to strengthen district mental health services in the province. Three district-based mental health teams have been created to work with PHC, hospitals, the non-health government sector, NGOs and the community. While they will provide promotive and preventive mental healthcare, their effectiveness and sustainability depend on supportive, collaborative relationships among all stakeholders.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. We are grateful to Dr Gwen Ramokgopa, Prof. Mkhululi Lukhele, Dr Monica Springfield and Dr Medupe Modisane, who gave their full support to the MHTAC during their time in office between 2018 and 2020. All government officials and mental health professionals who participated in MHTAC meetings are acknowledged for their contributions to the recovery plan and strengthening mental healthcare services, with particular mention of Ms Elma Burger, Dr Ora Gerber, Mr Jacques Labuschagne, Dr Kagisho Maaroganye, Ms Radisha Sukhlal, Dr Catherine Sibeko, and (posthumously) Prof. Bernard Janse van Rensburg. Author contributions. LJR conceptualised the article and drafted the manuscript. MYHM and FYJ provided content input, review and editing of the work.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. Principles for the Protection of Persons with Mental Illness and the Improvement of Mental Health Care: Adopted by General Assembly resolution 46/119 of 17 December 1991. https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/PersonsWithMentalIllness.aspx (accessed 6 January 2021). [ Links ]

2. National Department of Health, South Africa. White Paper for the transformation of the health system in South Africa. Notice 667 of 1997. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/17910gen6670.pdf (accessed 26 April 2021). [ Links ]

3. Thornicroft G, Deb T, Henderson C. Community mental health care worldwide: Current status and further developments. World Psychiatry 2016;15(3):276-286. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20349 [ Links ]

4. Lazarus R. Managing de-institutionalisation in a context of change: The case of Gauteng, South Africa. S Afr Psychiatry Rev 2005;8(2):65-69. https://www.ajol.info/index.php/ajpsy/article/view/30186/22805 (accessed 6 January 2021). [ Links ]

5. Moosa M, Jeenah F. Community psychiatry: An audit of the services in southern Gauteng. S Afr J Psychiatry 2008;14(2):36-43. [ Links ]

6. Robertson LJ, Szabo CP. Community mental health services in southern Gauteng: An audit using District Health Information Systems data. S Afr J Psychiatry 2017;23:a1055. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v23i0.1055 [ Links ]

7. Makgoba MW. Report into the circumstances surrounding the deaths of mentally ill patients: Gauteng Province. South Africa: Office of the Health Ombud, 2 May 2017. http://healthombud.org.za/category/publications/reports/ (accessed 4 January 2021). [ Links ]

8. Moseneke J. The Life Esidimeni Arbitration Report. 2018. http://www.saflii.org/images/LifeEsidimeniArbitrationAwardpdf (accessed 4 January 2021). [ Links ]

9. South African Human Rights Commission. Report of the National Hearing on the Status of Mental Health Care in South Africa, March 2019. https://www.sahrc.org.za/index.php/sahrc-publications/hearing-reports (accessed 4 January 2021). [ Links ]

10. South African Government. Mental Health Care Act No. 17 of 2002. https://www.gov.za/documents/mental-health-care-act (accessed 6 January 2021). [ Links ]

11. World Health Organization. WHO mental health policy and service guidance package: Organisation of services for mental health. 2003. https://www.who.int/mental_health/policy/services/essentialpackage1v2/en/ (accessed 6 January 2021). [ Links ]

12. National Department of Health, South Africa. National Mental Health Policy Framework and Strategic Plan 2013 - 2020. Pretoria: NDoH, 2012. https://health-e.org.za/2014/10/23/policy-national-mental-health-policy-framework-strategic-plan-2013-2020/ (accessed 26 April 2021). [ Links ]

13. Lund C, Flisher AJ. A model for community mental health services in South Africa. Trop Med Int Health 2009;14(9):1040-1047. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02332.x [ Links ]

14. National Department of Health, South Africa. National Health Act, 2003: Policy guidelines for the licensing of residential and/or day care facilities for persons with mental illness and/or severe or profound intellectual disability. Government Gazette No. 41498, 16 March 2018. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201803/41498gon218b.pdf (accessed 26 April 2021). [ Links ]

15. National Department of Health, South Africa. Integrated Clinical Services Management (ICSM). Pretoria: NDoH, 2015 https://www.idealhealthfacility.org.za/docs/Integrated%20Clinical%20Services%20Manageme nt%20%20Manual%205th%20June%20FINAL.pdf (accessed 26 April 2021). [ Links ]

16. Thornicroft G, Ahuja S, Barber S, et al. Integrated care for people with long-term mental and physical health conditions in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry 2019;6(2):174-186. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(18)30298-0 [ Links ]

17. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs: Disability. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html (accessed 6 January 2021). [ Links ]

18. Arstein-Kerslake A, Flynn E. The General Comment on Article 12 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: A roadmap for equality before the law. Int J Hum Rights 2016;20(4):471-490. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642987.2015.1107052 [ Links ]

19. Bonnie RJ, Zelle H. Ethics in mental health care: A public health perspective. In: Mastroianni AC, Kahn JP, Kass NE, eds. The Oxford Handbook of Public Health Ethics. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190245191.013.2 [ Links ]

20. Robertson LJ, Makgoba MW. Mortality analysis of people with severe mental illness transferred from long-stay hospital to alternative care in the Life Esidimeni tragedy. S Afr Med J 2018;108(10):813-817. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2018.v108i10.13269 [ Links ]

21. World Health Organization. Prevention of mental disorders: Effective interventions and policy options. Summary report. Geneva: WHO, 2004. https://www.who.int/mental_health/evidence/en/prevention_of_mental_disorders_sr.pdf (accessed 26 April 2021). [ Links ]

22. Republic of South Africa. National Health Insurance Bill (B11-2019). https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gds_document/201908/national-health-insurance-bill-b-11-2019.pdf (accessed 24 April 2021). [ Links ]

23. Lund C, Kleintjies S, Campbell-Hall V, et al. Mental Health and Poverty Project. Mental health policy development and implementation in South Africa: A situation analysis. Phase 1: Country report. 31 January 2008. http://www.cpmh.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/SA_report.pdf (accessed 26 April 2021). [ Links ]

24. Docrat S, Besada D, Lund C. An evaluation of the health system costs of mental health services and programmes in South Africa. Cape Town: Alan J Flisher Centre for Public Mental Health, University of Cape Town, 2018. https://doi.org/10.25375/UCT.9929141 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

L J Robertson

lesley.robertson@wits.ac.za

Accepted 23 February 2021