Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.111 n.2 Pretoria Feb. 2021

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2021.v111i2.15388

IN PRACTICE

ISSUES IN MEDICINE

Parental access to hospitalised children during infectious disease pandemics such as COVID-19

A GogaI, II; U FeuchtIII, IV, V, VI; S PillayVII; G ReubensonVIII; P JeenaIX; S MadhiX, XI; N T MayetXII; S VelaphiXIII; N McKerrowXIV, XV, XVI; L R MathivhaXVII; N MakubaloXVIII; R J GreenXIX; G GrayXX

IFC Paed (SA), PhD; South African Medical Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa

IIFC Paed (SA), PhD; Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

IIIFC Paed (SA), PhD; Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

IVFC Paed (SA), PhD; Tshwane District Health Services, Gauteng Department of Health, City of Tshwane, South Africa

VFC Paed (SA), PhD; Research Centre for Maternal, Fetal, Newborn and Child Health Care Strategies, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

VIFC Paed (SA), PhD; Maternal and Infant Health Care Strategies Research Unit, South African Medical Research Council, Pretoria, South Africa

VIIFC Paed (SA), Cert Neonatology (SA): Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

VIIIFC Paed (SA); Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IXFC Paed (SA), PhD; Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

XFC Paed (SA), PhD; South African Medical Research Council: Vaccines and Infectious Diseases Analytics Research Unit, School of Pathology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

XIFC Paed (SA), PhD; Department of Science and Technology/National Research Foundation, South African Research Chair Initiative in Vaccine Preventable Diseases, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

XIIMB ChB: National Institute of Communicable Diseases, Johannesburg, South Africa

XIIIFC Paed (SA), PhD; Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

XIVFC Paed (SA); Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

XVFC Paed (SA); Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

XVIFC Paed (SA); Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, KwaZulu-Natal Department of Health, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

XVIIPGDHSE; Department of Critical Care Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

XVIIIFC Paed (SA): District Clinical Specialist Team, Eastern Cape Department of Health, Nelson Mandela Bay, South Africa

XIXFC Paed (SA), DSc; Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

XXFC Paed (SA), DSc; South African Medical Research Council, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in many hospitals severely limiting or denying parents access to their hospitalised children. This article provides guidance for hospital managers, healthcare staff, district-level managers and provincial managers on parental access to hospitalised children during a pandemic such as COVID-19. It: (i) summarises legal and ethical issues around parental visitation rights; (ii) highlights four guiding principles; (iii) provides 10 practical recommendations to facilitate safe parental access to hospitalised children; (iv) highlights additional considerations if the mother is COVID-19-positive; and (v) provides considerations for fathers. In summary, it is a child's right to have access to his or her parents during hospitalisation, and parents should have access to their hospitalised children; during an infectious disease pandemic such as COVID-19, there is a responsibility to ensure that parental visitation is implemented in a reasonable and safe manner. Separation should only occur in exceptional circumstances, e.g. if adequate in-hospital facilities do not exist to jointly accommodate the parent/caregiver and the newborn/infant/child. Both parents should be allowed access to hospitalised children, under strict infection prevention and control (IPC) measures and with implementation of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), including handwashing/sanitisation, face masks and physical distancing. Newborns/infants and their parents/caregivers have a reasonably high likelihood of having similar COVID-19 status, and should be managed as a dyad rather than as individuals. Every hospital should provide lodger/boarder facilities for mothers who are COVID-19-positive, COVID-19-negative or persons under investigation (PUI), separately, with stringent IPC measures and NPIs. If facilities are limited, breastfeeding mothers should be prioritised, in the following order: (i) COVID-19-negative; (ii) COVID-19 PUI; and (iii) COVID-19-positive. Breastfeeding, or breastmilk feeding, should be promoted, supported and protected, and skin-to-skin care of newborns with the mother/caregiver (with IPC measures) should be discussed and practised as far as possible. Surgical masks should be provided to all parents/caregivers and replaced daily throughout the hospital stay. Parents should be referred to social services and local community resources to ensure that multidisciplinary support is provided. Hospitals should develop individual-level policies and share these with staff and parents. Additionally, hospitals should ideally track the effect of parental visitation rights on hospital-based COVID-19 outbreaks, the mental health of hospitalised children, and their rate of recovery

During infectious disease pandemics such as COVID-19, there is often a dilemma as to whether hospitalised children should be separated from their parents: in many settings, health facilities have severely limited or denied parents access to their hospitalised children, and thus restricted hospitalised children's access to their parents. Childhood is a period of physical, psychological and social vulnerabilities, which may be exacerbated during illness. In the face of COVID-19, the physical, emotional and social repercussions associated with hospital admission may be amplified by the effects of social distancing, infection prevention and control (IPC) measures, and non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) such as personal protective equipment (PPE). This article provides guidance for hospital managers, healthcare staff, district-level managers and provincial managers on parental access to hospitalised children during a pandemic such as COVID-19. It summarises legal and ethical issues around parental visitation rights, highlights four guiding principles, provides 10 practical recommendations to facilitate sate parental access to hospitalised children, highlights additional considerations if the mother is COVID-19-positive, and provides considerations for fathers.

Parental presence during hospitalisation has several benefits for both parent and child, including parental stress reduction as parents become more informed and involved in caring for their hospitalised children, leading to greater parental satisfaction.[1] Systematic reviews have demonstrated that parents and healthcare providers recognise the value of parents being with their child during hospitalisation.[2,3] This is especially pertinent to newborns, where kangaroo mother care (KMC) is associated with significantly shorter hospital stay, less frequent readmission and increased maternal satisfaction.[4] In addition, skin-to-skin contact in the first hours of life is associated with reduced postpartum haemorrhage risk, decreased rates of postpartum depression and anxiety, and increased odds of successful breastfeeding.[5]

In the context of COVID-19, there has been rapid, continual assimilation of data quantifying the risks and outcomes of newborns born to mothers with COVID-19. While individual reports have reported possible cases of intrauterine SARS-CoV-2 transmission, breastmilk transmission has not been described. However, horizontal transmission through respiratory spread is a recognised mode of transmission. Cluster outbreaks of COVID-19 have occurred in mothers' lodges and KMC units, associated with adverse outcomes. These have led to cautious expert opinions and individualised management principles, including predelivery counselling with temporary post-delivery separation of SARS-CoV-2-infected mothers from their infants, with expressed breastmilk feeding using strict infection control practices.[6,7] However, the World Health Organization recommends that mother-infant pairs should remain together while rooming in throughout the day and night, practising skin-to-skin contact, including KMC, particularly in the immediate postpartum period and during establishment of breastfeeding, whether or not mothers or their infants have suspected or confirmed

COVID-19.[8] This recommendation is also endorsed by the European Paediatric Association.[9] Separation of mother-infant pairs could theoretically minimise the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission; however, at the time of writing this article, there was no compelling evidence suggesting benefit of separation.[10] Additionally, separation may not prevent infection (as described in a case series from Wuhan), and it does not prevent infection after discharge.[6] It could also disrupt newborn physiology (higher heart and respiratory rates, and lower glucose levels in newborns).[10] As noted by the Royal College of Midwives, Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and Paediatricians in the UK, 'routine precautionary separation of a mother and a healthy baby should not be undertaken lightly, given the potential detrimental effects on feeding and bonding'.[11] Isolation is a significant stressor for newborns; for infants already infected with SARS-CoV-2, isolation could worsen the disease course. Separation also increases maternal stress levels, increasing heart rate and salivary Cortisol levels, and in the context of a pandemic this additional suffering may worsen the mother's disease course.[10] Current evidence shows that the risk of newborn infection is very low, and most infected newborns do not have significant morbidity.[5] The benefit of KMC to the infant-mother dyad outweighs the risks, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Consequently, the mother/ caregiver should be empowered and given the option to practise KMC with explanation of risks and benefits, with emphasis on IPC and NPIs, to reduce the risk of transmission. Infant-mother dyads should remain together if possible, and KMC should be encouraged; these infants do not need to be nursed in an incubator if they remain isolated with their mother - when not doing skin-to-skin they can be in a crib next to the mother's bed. The alternative, which is complete cessation of visitation during a pandemic, while not empirically studied, would undoubtedly add to parental stress and may have subsequent deleterious effects on infant development.[12] Lastly, separation could interfere with maternal milk production and supply, disrupting feeding and innate and specific immune protection.[10]

Experiences in the South African context and abroad

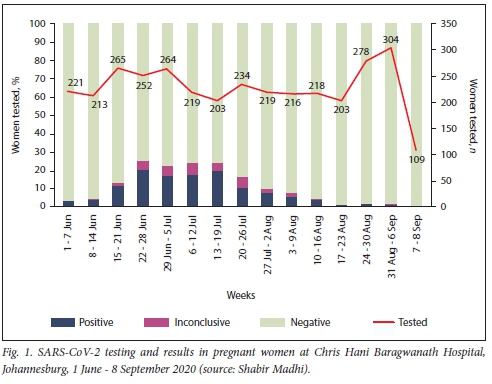

In May 2020, despite IPC measures, 9 mothers, 2 babies, 4 doctors and a nurse tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 at the General Justice Gizenga Mpanza Regional Hospital (previously Stanger Hospital) in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa (SA).[13] The source of infection was probably a lodger mother who had undisclosed close contact with a COVID-19 case. Similarly, in June 2020, a COVID-19 outbreak occurred in the KMC ward at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital (CHBAH), Johannesburg, SA (S Velaphi, personal communication). Testing of pregnant women at CHBAH demonstrated that their COVID-19 positivity rates mirror the positivity rates in the community (Fig. 1). The effect of strict in-hospital IPC and NPI measures on COVID-19 positivity in maternal, child or KMC wards during the second wave remains to be measured, including whether patient positivity sparks hospital outbreaks.

A Lancet Child and Adolescent Health publication reporting data from a New York hospital during March - May 2020 states that of the 120 babies born to 116 COVID-positive mothers, none had acquired SARS-CoV-2 by 1 month of age.[14] All neonates who roomed in with their mothers were nursed in a closed Giraffe isolette (General Electric Healthcare, USA); skin-to-skin contact was initiated in the delivery room with appropriate IPC, and infants were held by their mothers during feeding after appropriate hand hygiene and breast cleansing, with maternal surgical mask use. All mothers were allowed to breastfeed. Mothers of neonates admitted to the specialised neonatal unit were only allowed to visit 14 days after they tested positive, if they had been afebrile for at least 72 hours.

Legal rights and ethics around parental visitation rights

As eloquently articulated by McQuoid-Mason,[15] the ban on parental visitation to their hospitalised children is a violation of children's rights, as per the SA Constitution, and in terms of acting in the 'best interests of the child' and the 'best interests standard' (Childrens Act No. 38 of 2005). He argues that the restrictions on parental visitation are not 'reasonable and justifiable' and that 'less restrictive means' can be used to prevent the spread of SARS-CoV-2. Hospital policies that limit visitors, and by extension limit mobility, are rooted in consequentialist ideals.[16] This means that such limitations must have a positive impact on the greater constituency. It can be argued that restricting parental access to hospitalised children is entrenched within utilitarianism, i.e. maximising the good for the highest number of people, and libertarianism, which states that the 'the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community against his will, is to prevent harm to another'.[17] The current pandemic justifies limiting liberties using utilitarianism and libertarianism and the draconian limitation of parents at the bedside only if there are no less intrusive measures of preventing the spread of SARS-CoV-2. In 1984, the Siracusa Principles, outlined by the United Nations, coalesced the conditions necessary to legitimise restrictive public health measures in the setting of a pandemic.[18] Importantly, these principles stipulate that the least restrictive measures of interference and disruption should be used to achieve the public health goal. In the context of COVID-19, the proper application of PPE can contain and reduce spread.[19,20] However, the prospect of allowing asymptomatic carriers, who are potentially contagious, into any neonatal or paediatric unit is daunting. This anxiety stems from staff members and other mothers coming into contact with someone who is COVID-19-positive. Even with PPE a zero risk to others cannot be guaranteed, and therefore health services cannot guarantee 'first do no harm' for all. However, the risk of SARS-CoV-2-positive mothers transmitting infection and causing severe illness in the baby has been low until now, so it is reasonable to keep infants with their mothers even if the mother is COVID-19-positive, provided she is well enough to care for her baby and follows strict IPC measures. Lastly, the ethics of contrasting hospital policies in the same subdistrict/local area (whereby some hospitals allow parental access while others do not) is disingenuous because the guiding principle is not based on facts particular to the case or the community, but instead on hospital preference.[17]

Systems needed to ensure parental access to hospitalised children during COVID-19

Within the context of infectious disease outbreaks, such as the current COVID-19 pandemic, we recommend avoiding the separation of parents and hospitalised children. Newborns/infants/children and their parents/caregivers have a reasonably high likelihood of having a similar COVID-19 status. The child and parent should therefore be considered and managed as a dyad rather than as separate individuals. However, COVID-19-positive mothers may spread SARS-CoV-2 to other mothers or to hospital staff, so a positive SARS-CoV-2 result in either member of the dyad should prompt management of both as potentially infectious. Children should have access to both parents during their hospitalisation. This approach is guided by four principles:

• First do no physical, emotional or social harm. The best interests (nutrition, health, development and wellbeing) of every child should be prioritised. Children should not be harmed, and all decisions should not cause harm to other children, caregivers or staff.

• Maximise the good for the highest number of individuals, while causing no harm.

• Apply the least restrictive measures of interference and disruption to achieve the public health goal.

• Consider the feasibility of implementing recommended protocols in different social, cultural and geographical contexts, including settings with limited resources.

Consequently, we provide 10 recommendations (Box 1), namely:

(i) avoid separation of the hospitalised child and his or her parents, except under exceptional circumstances; (ii) newborns/infants/children and their parents/caregivers are likely to have similar COVID-19 status and should be managed as a single dyad rather than as separate individuals; (iii) promote, support and encourage breastfeeding, or breastmilk feeding, and discuss skin-to-skin care of newborns with the mother/caregiver; (iv) provide surgical masks to all parents/caregivers accompanying a child to hospital, with daily replacement thereof throughout the hospital stay; (v) every hospital is mandated to provide lodger/boarder facilities for mothers, with stringent IPC monitoring, surgical masks, physical distancing, regular handwashing and twice daily COVID-19 screening - the lodger facility should be well ventilated and not overcrowded; (vi) reinforce administrative controls to reduce risk; (vii) reinforce engineering controls to reduce risk; (viii) if parental separation is unavoidable, it should be limited to as short a period as possible, and innovative methods should be implemented to facilitate contact, including daily phone calls, photographs and video calls, and skin-to-skin interactions by a caregiver or staff member designated to care for the newborn/infant/child; (ix) engage with communities to explore the repurposing of homes/community halls around the hospital to accommodate dyads; and (x) link parents to social services and/or local community resources, as policies and practices (e.g. IPC measures/NPIs) concerning parental access to hospitalised children during COVID-19 could cause or exacerbate stress.

We highlight additional considerations if the mother is COVID-19-positive (Box 2), and special considerations for fathers (Box 3).

Hospitals should develop individual-level policies guided by evidence, feasibility, experience and ethical principles of utilitarianism and libertarianism, and share these with staff and parents. Additionally, hospitals should ideally track the effect of parental visitation rights on hospital-based COVID-19 outbreaks, the mental health of hospitalised children, and their rate of recovery.

Conclusions

It is a child's right to have access to his or her parents during hospitalisation, and parents should have access to their hospitalised children, but there is a responsibility to ensure that this is done in a reasonable and safe manner. During infectious disease pandemics, such as COVID-19, the coverage of NPIs and IPC measures must be expanded to facilitate reasonable access of parents to their hospitalised children. The impact of this on hospital-based COVID-19 outbreaks, the mental health of hospitalised children, and their rate of recovery should be monitored.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. South African Medical Research Council.

Author contributions. AG: conceptualised article, wrote drafts incorporated comments, finalised drafts. UF: contributed reviews and papers, contributed to the discussions, assisted with summarising consensus and main points, reviewed all drafts and the final document. SP: contributed reviews and papers, contributed to the discussions, reviewed all drafts and the final document. GR: reviewed all drafts, contributed to the discussions and assisted with consensus. PJ: reviewed and contributed to all drafts and the final document. SM: reviewed and contributed to all drafts and the final document, and contributed the data on testing in pregnant women. NM: contributed to all drafts and reviewed the final document. SV: reviewed all drafts and the final document and contributed experience from a local setting. NMcK: reviewed all drafts and the final document and contributed to the discussions. LRM: reviewed all drafts and the final document and contributed to the discussions. NM: reviewed all drafts and the final document and contributed to the discussions. RJG: reviewed all drafts and the final document. GG: assisted with conceptualisation of the article, and reviewed all drafts and the final document.

Funding. South African Medical Research Council.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Melnyk B, Alpert-Gillis L, Feinstein N, et al. Creating opportunities for parent empowerment. Program effects on the mental health/coping outcomes of critically ill young children and their mothers. Pediatrics 2004;113(6):e597-607. https://doi.org/10.1542/PEDS.113.6.E597 [ Links ]

2. Shields L, Zhou H, Pratt J, Taylor M, Hunter J, Pascoe E. Family-centred care for hospitalised children aged 0 - 12 years. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev 2012, Issue 10. Art. No.. CD004811. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004811.pub3 [ Links ]

3. Watts R, Zhou H, Taylor M, Munns A, Ngune I. Family-centered care for hospitalized children aged 0-12 years. A systematic review of qualitative studies. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2014;12(7):204-283. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2014-1683 [ Links ]

4. Jafari M, Farajzadeh F, Asgharlu Z, Derakhshani N, Asl YP. Effect of kangaroo mother care on hospital management indicators. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Educ Health Promot 2019;8:96. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_310_18 [ Links ]

5. Boscia C Skin-to-skin care and COVID-19. Pediatrics 2020;146(2):e20201836. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-1836 [ Links ]

6. Zeng, L, Xia S, Yuan W, et al. Neonatal early-onset infection with SARS-CoV-2 in 33 neonates born to mothers with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Pediatr 2020;174(7):722-725. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0878 [ Links ]

7. De Carvalho WB, Gibelli MABC, Krebs VLJ, Calil VMLT, Johnston C. Expert recommendations for the care of newborns of mothers with COVID-19. Clinics 2020;75(2):e1932. https://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2020/e1932 [ Links ]

8. World Health Organization. Breastfeeding and COVID-19, Scientific Brief. 23 June 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/breastfeeding-and-covid-19 (accessed 10 October 2020). [ Links ]

9. Wilhams J, Namazova-Baranova L, Weber M, et al. The importance of continuing breastfeeding during coronavirus disease-2019. In support of the World Health Organization Statement on Breastfeeding during the Pandemic. J Pediatr 2020;223:234-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.05.009 [ Links ]

10. Stuebe A. Should infants be separated from mothers with COVID-19? First, do no harm. Breastfeed Med 2020;15(5):351-352. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2020.29153.ams [ Links ]

11. Royal College of Midwives, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in pregnancy. Information for health care professionals. Version II. 24 July 2020. https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/guidelines/2020-07-24-coronavirus-covid-19-infection-in-pregnancy.pdf (accessed 10 October 2020). [ Links ]

12. Turpin H, Urben S, Ansermet F, Borghini A, Murray MM, Müller-Nix C. The interplay between prematurity, maternal stress and childrens intelligence quotient at age ILA longitudinal study Sei Rep 2019;9:450. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-36465-2 [ Links ]

13. Duma N. Two babies, 14 adults test positive for COVID-19 at KZN hospital. Eye Witness News, 5 May 2020. https://ewn.co.za/2020/05/05/two-babies-14-adults-test-positive-for-covid-19-in-kzn-hospital (accessed 10 October 2020). [ Links ]

14. Salvatore C, Han J-Y, Acker KP, et al. Neonatal management and outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. An observation cohort study Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2020;4(10):721-727. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30235-2 [ Links ]

15. McQuoid-Mason DJ. Is the COVID-19 regulation that prohibits parental visits to their children who are patients in hospital invalid in terms of the Constitution? What should hospitals do? S Afr Med J 2020;110(11):1089-1087. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2020.v110i11.15273 [ Links ]

16. Wynia M. Ethics and public health emergencies. Restrictions on liberty Am J Bioeth 2007;7(2):1-5. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265160701577603 [ Links ]

17. Murray P, Swanson J. Visitation restrictions. Is it right and how do we support families in the NICU during COVID-19? J Perinatal 2020;40:1576-1581. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-020-00781-1 [ Links ]

18. United Nations. Siracusa Principles on the Limitation and Derogation Provisions in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. 28 September 1984. https://undoes.org/pdf?symbol=en/E/CN.4/1985/4 (accessed 29 August 2020). [ Links ]

19. Cook TM. Personal protective equipment during the coronavirus disease (COVID) 2019 pandemic - a narrative review. Anaesthesia 2020;75(7):920-927. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15071 [ Links ]

20. Chu DK, Aki EA, Duda S, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. A systematic review and metaanalysis. Lancet 2020;395(10242):1973-1987. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

A Goga

ameena.goga@mrc.ac.za

Accepted 7 December 2020