Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.109 n.9 Pretoria Sep. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2019.v109i9.14313

IN PRACTICE

HEALTHCARE DELIVERY

Increasing deceased organ donor numbers in Johannesburg, South Africa: 18-month results of the Wits Transplant Procurement Model

M de JagerI; C WilmansII; J FabianIII, IV; J F BothaV, VI; H R EtheredgeVII, VIII

IRN; Transplant Unit, Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre, School of Clinical Medicine, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIBPharm; Transplant Unit, Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre, School of Clinical Medicine, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIIMB BCh, FCP (SA), Cert Nephrology (SA); Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IVMB BCh, FCP (SA), Cert Nephrology (SA) Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre, School of Clinical Medicine, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

VMB BCh, FCS (SA) Transplant Unit, Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre, School of Clinical Medicine, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

VIMB BCh, FCS (SA); School of Clinical Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

VIIPhD; Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

VIIIPhD; Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre, School of Clinical Medicine, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

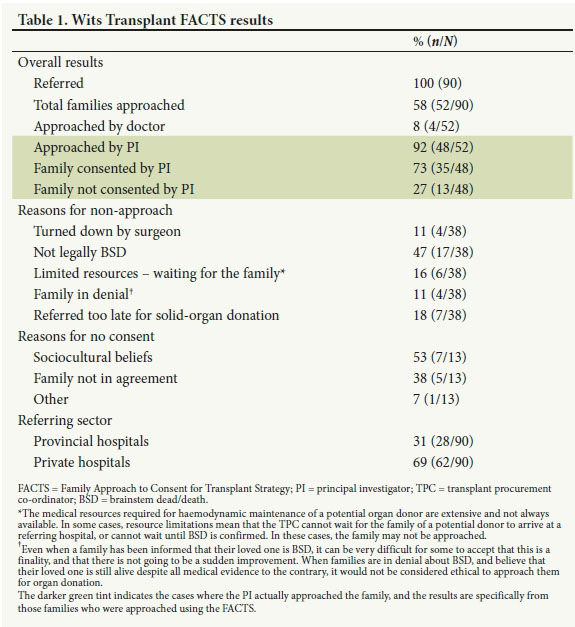

In 2016, deceased-donor organ procurement at Wits Transplant, based at Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre in Johannesburg, South Africa (SA), was in a state of crisis. As it is the largest-volume solid-organ transplant unit in SA, and as we aspire to provide transplant services of an international standard, the time to address our procurement practice had come. The number of deceased donors consented through our centre was very low, and we needed a radical change to improve our performance. This article describes the Wits Transplant Procurement Model - the result of our work to improve procurement at our centre. The model has two core phases, one to increase referrals and the other to improve our consent rates. Within these phases there are several initiatives. To improve referrals, the threefold approach of procurement management, acknowledgement and resource utilisation was developed. In order to 'convert' referrals into consents, we established the Wits Transplant 'Family Approach to Consent for Transplant Strategy' (FACTS). Since initiation of the Wits Transplant Procurement Model, both our referral numbers from targeted hospitals and our conversion rates have increased. Referrals from targeted hospitals increased by 54% (from 31 to 57). Our consent rate increased from 25% (n=6) to 73% (n=35) after the initiation of Wits Transplant FACTS. We hope that other transplant centres in SA and further afield in the region will find this article helpful, and to this end we have created a handbook on the Wits Transplant Procurement Model that is freely available for download (http://www.dgmc.co.za/docs/Wits-Transplant-Procurement-Handbook.pdf).

In 2016, deceased-donor organ procurement at Wits Transplant, based at Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre in Johannesburg, South Africa (SA), was in a state of crisis. As it is the largest-volume solid-organ transplant unit in SA,[1] and as we aspire to provide transplant services of an international standard, the time to address our procurement practice had come. The human resources component of Wits Transplant was overhauled, with incoming management determined to address some of the shortfalls. The number of deceased donors consented through our centre was very low, and we needed a radical change to improve our performance. The goal of new management was to identify gaps in our approach and implement a strategy that would increase transplants from deceased donors.

The number of deceased donors consented through a procurement programme is often a barometer of its success,[2] but consent rates cannot improve in the absence of a wider strategy to increase referrals. Management aimed to improve the transplant procurement co-ordinator (TPC)'s opportunity to obtain consent by increasing referral numbers from hospitals in the region and reviewing the individual consenting process for each TPC.

We describe the Wits Transplant Procurement Model in this article, detailing some of our initiatives that appear to have worked. We hope that other transplant centres in SA and further afield in the region will find it helpful. We have created a handbook on organ procurement that is freely available for download (http://www.dgmc.co.za/docs/Wits-Transplant-Procurement-Handbook.pdf) and provides practical details on the Wits Transplant Procurement Model.

Deceased-donor organ shortages: The global context

Globally, persistent shortages of deceased-donor organs remain one of the greatest challenges to expanding access to solid-organ transplantation for individuals with end-stage organ failure.[3] In many countries, attempts have been made to increase deceased organ donation, with varying success. Generally, with successful initiatives, multipronged approaches include various combinations of the following: (i) legislative change, for example using the 'opt-out' rather than the 'opt-in' system; (ii) substantial government buy-in; (iii) robust hospital-based programmes that facilitate quick identification and referral of potential donors; and (iv) extensive human, infrastructural and health system resources to ensure sustainability.[4,5] Deceased-donor shortages persist in SA, resulting in the deaths of many patients waiting for organ transplants.[16]

General roles of the TPC

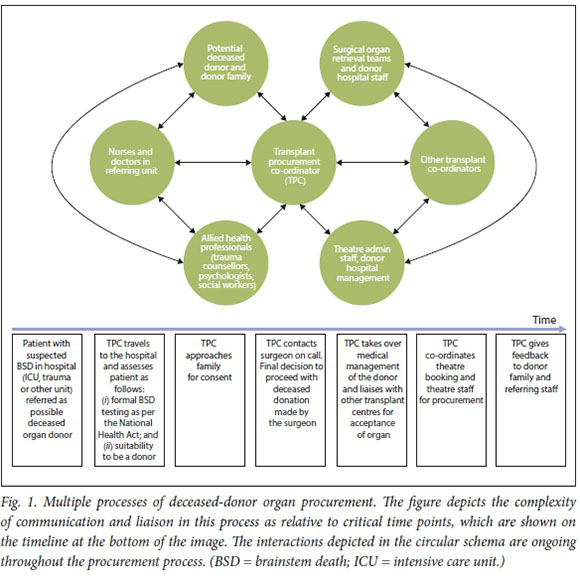

The exact scope of practice for TPCs varies from country to country, but their job encompasses some general responsibilities and duties.[7]These include promoting referrals, obtaining consent from the families of deceased donors, medical maintenance of the donor, and interprofessional communication (Fig. 1).

Increasing referrals

Within the system, TPCs are required to work towards increased awareness of organ donation across potential referral hospitals in their catchment area. The premise of ongoing health professional education is that the more health professionals are informed about various aspects of organ donation, the more likely they will be to refer a potential donor. Health professional education in transplantation requires TPCs to be physically present at referring hospitals, visibly build relationships, and create networks with hospital staff. When a potential deceased donor is referred, it is necessary for the TPC to meet the referring staff and assess the referral for appropriateness. Even when a referral is not advanced to the family approach stage, the TPC can use the opportunity for 'bedside education' for the nurses and doctors involved. The physical presence of the TPC at the referring hospital is a demonstration of commitment to every referral that is made.

Converting referrals to consents

Critical to deceased organ donation is facilitating a conversation between the TPC and the potential donor family. The outcome of this conversation is the number of referrals that are 'converted' into consented donors (known as the 'conversion rate'). The process of approaching a grieving family and seeking their consent to donate the organs of a deceased loved one requires a deep empathy and sensitivity to the family's situation and emotions. Internationally, TPCs are trained on how to approach a family and the exact nature of the consent conversation.

Part of the drive to increase deceased-donor numbers worldwide is the adoption of 'designed communication strategies', which are used by TPCs when approaching families of potential deceased donors for consent. [8] International studies are unanimous in identifying this aspect of the transplant process as one that is often neglected, and one where the approach used by the TPC can have a tangible influence on whether or not consent is obtained from the family. The UK, Spain, the USA, Australia, New Zealand and Belgium have all adopted designed communication strategies that TPCs are obliged to utilise when they approach families in hospitals.®

Across each country, the designed communication strategy varies depending on legislation (for instance whether a country is 'opt in' or 'opt out'), the structure of the hospital system, and whether there is an accessible national register. Most designed communication strategies are time-based, with pointers on how TPCs should raise pertinent issues with families at the appropriate time.

The basis of such communication strategies is that the way a TPC approaches a family, the words and sentences that are used and the posing of questions about organ donation can influence decision-making without being coercive. Designed communication approaches emphasise sensitivity and empathy, and most stress that the timing of each aspect is critical - families need time to think and consider, but they should not be in a position where a decision is deferred.

Communication and medical maintenance

TPCs are ultimately responsible not only for obtaining consent from the families of deceased donors, but also for the medical management of the donor and inter-hospital liaison once consent has been granted.[9] The role of the TPC is time critical, as a potential donor may become haemodynamically unstable or unsuitable for donation if a long period of time elapses.

The medical processes around deceased organ donation are complicated and present several pressure points that the TPC navigates. As well as maintaining the organ function of the donor, communication is vital, as transplant procedures take place at different hospitals across the country, depending on where a recipient is based in relation to the donor and the expertise of the transplant team. Many different centres therefore need to come together when a deceased donor is available. This task involves the TPC imparting a very large amount of complex information to multiple parties in a timely and effective manner.[10]

Deceased-donor procurement in SA: The local context of Wits Transplant

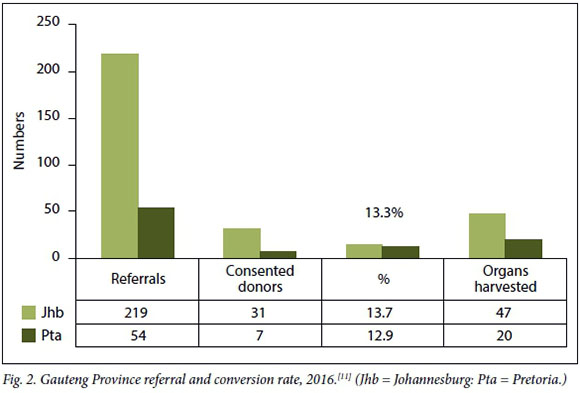

Within the SA transplant context, we identified two major areas of improvement for transplant procurement at our centre. These were the low number of potential deceased-donor referrals, and a very low conversion rate (Fig. 2).

Deceased-donor numbers in SA have been low for many years, and the transplant community is aware that change is needed; however, a successful strategy to increase donor numbers does not appear to have been developed. Although a multifaceted approach to deceased donation is encouraged internationally, any such strategy in SA needs to consider our unique socioeconomic and healthcare framework and be adapted to suit our needs. Finding this balance in deceased-donor procurement and transplant programmes is complicated by the need for upfront, ongoing human and other capital investment. Such capital investment is often hard to justify in low- to middle-income settings such as SA, where state-based healthcare provision is generally underfunded.[12, 13] Human and other capital investment is particularly problematic when it comes to high-end, expensive modalities like organ transplantation, which is required by relatively few people and is much more expensive than managing competing health priorities such as HIV, tuberculosis and emerging non-communicable diseases, which affect the lives of many.

It is perhaps unsurprising that very few TPCs are employed in the SA health sector. In total, 16 TPCs service the organ procurement needs of the country, with 50% (8/16) based at private sector institutions and the other half in the state sector (Anja Meyer, Chairperson, South African Transplant Coordinator Society, personal communication 13 August 2019). In the absence of a national mandate to employ TPCs and capacitate integrated transplant programmes, the decision on whether to make this resource available is ad hoc and depends on the individual priorities and service provision mandate of each hospital.

SA does not have a national, accredited training programme for TPCs, and there are no national protocols to guide those who choose to refer potential deceased donors to TPCs[14] Moreover, a strategy that could assist TPCs in approaching potential donor families has never been formalised, or tested in a research setting. The approach and consent process is therefore often improvised, and opportunities for conversion maybe lost. Moreover, the approach is not necessarily followed through to its conclusion, which entails informing families and referring teams about what organs were used for donation, and providing some information about the outcome.

A substantial body of published research from SA suggests that there are many reasons for low referral rates. These include a wider context where lack of trust in transplantation (on the part of both the public and health professionals), sociocultural and familial preclusions and suspicions about the medical system converge to shape attitudes to organ donation. There are also numerous barriers to referral at hospital level, including misunderstandings of the transplant process on the part of health professionals, lack of a distinct referral policy for potential donors, and unwillingness to have difficult conversations with families about death and poor prognoses in hospital.[15, 16]

Some published work has explored the conversion rate, primarily qualitatively, by assessing the reasons given by families when refusing consent to organ donation; however, these publications are outdated.[17] Perceptions are that 'cultural' barriers prevent families from consenting, but there is literature from SA to the contrary,[16] pointing to the need for highly trained staff who are sensitive to the issues and able to provide information to families that they can use in the decision-making process. While international literature suggests that the conversation between the TPC and potential donor families is essential to facilitate consent and increase the conversion rate, this has not been explored in SA. An in-depth study has been recommended as part of the findings from a larger research project.[10]

The Wits Transplant Procurement Model

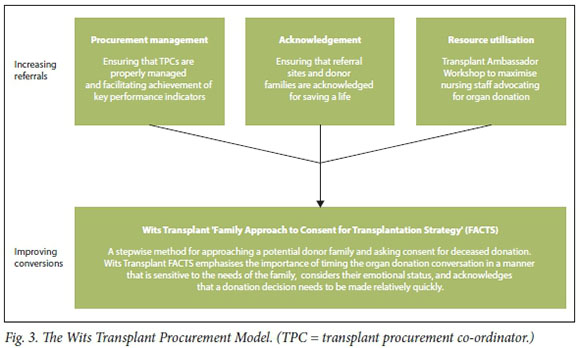

To improve the number of transplants from deceased donors at Wits Transplant, we devised a model for increasing the number of deceased donors referred to - and consented by - the TPC at our centre (Fig. 3). There are two components to this model: (i) a three-pronged initiative to increase referrals that encompasses the procurement management, acknowledgement and resource utilisation strategy; and (ii) the Wits Transplant 'Family Approach to Consent for Transplant Strategy' (FACTS).

Increasing referrals

Procurement management

Through evaluating the procurement situation at Wits Transplant in 2016, new management recognised that our TPCs were not always well managed, and as a result our response to referrals was haphazard. As our centre responds to referrals at 26 hospitals across three provinces, some of the challenges were understandable, though unacceptable. In some cases, TPCs did not respond to referrals, losing out on the opportunity for bedside education on transplantation and to demonstrate our commitment to deceased donation. Furthermore, initiatives to create awareness of organ donation among health professionals were lacking, and strengthening of our commitment to transplant education in hospitals was needed. This situation called for much more active management of our TPCs. The initiatives we implemented to shore up transplant management and procurement key performance indicators are detailed in the handbook.

Acknowledgement

Expanding on our commitment to manage our procurement team more effectively, we felt that physically visiting each hospital when a donor was referred was not sufficient. It was decided that more could be done to maintain the relationships built at the bedside when evaluating and consenting donors. We also wanted to provide continuity and follow-up for those who referred potential donors to us. To this end, we hand out certificates of appreciation at the end of each year (2017 and 2018 to date). These certificates acknowledge the role that each nurse and doctor has played in saving a life of a recipient through referring a potential donor whose family subsequently consented to organ donation.

Resource utilisation strategy: Transplant Ambassador Programme

The Southern African Transplant Society Meeting of 2017 highlighted both the very low referral/conversion rate (Fig. 2) and the limited human resources for transplant procurement in Gauteng Province. The Transplant Ambassador Programme is targeted at nurses. Through relationship building and interactive annual education workshops, we aim to increase the number of nurses working to promote organ donation in the province. It was felt that facilitating favourable attitudes to organ donation through the programme could improve referral numbers and also deploy more resources to the cause of organ donation.

So far, Wits Transplant has hosted two full-day Transplant Ambassador Workshops. The workshops aim to empower nursing staff working in intensive care and trauma units to become ambassadors for organ donation and transplantation. To date, workshops have been attended by 100 registered nurses. Educational funding for the workshops is secured from pharmaceutical companies by the Wits Transplant manager, which allows us to host the workshops at a conference venue. Each delegate receives a certificate of completion of the workshop as well as a transplant ambassador badge.

The badge identifies transplant ambassadors within their hospital and aims to spark conversations about organ donation and transplantation.

Improving our conversion rate: Wits Transplant FACTS

In January 2018, the TPC at Wits Transplant commenced a quality improvement and research intervention utilising a designed communication strategy when approaching potential donor families and seeking consent. The communication strategy came to be known as Wits Transplant FACTS. The TPC (MdJ) is the principal investigator (PI) of this study, and approval was obtained from the Wits Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) (ref. no. M171144). The strategy was based on that published by the National Health Service Blood and Transplant Group (NHSBT) in the UK.[18] This is a stepwise process that guides TPCs in the most effective way to initiate and follow through the organ donation conversation. It involves planning the approach with the management team and the words and language chosen, emphasising how different sentences can be used in different situations to achieve the best possible result.

Over the past 18 months, the PI has adapted the NHSBT strategy to our setting, with modifications that are appropriate for SA, and it is this communication model that has evolved into Wits Transplant FACTS. In this study, the PI functioned as her own time-based control, comparing her conversions pre-intervention with those from January 2018 forward - from the time Wits Transplant FACTS was initiated.

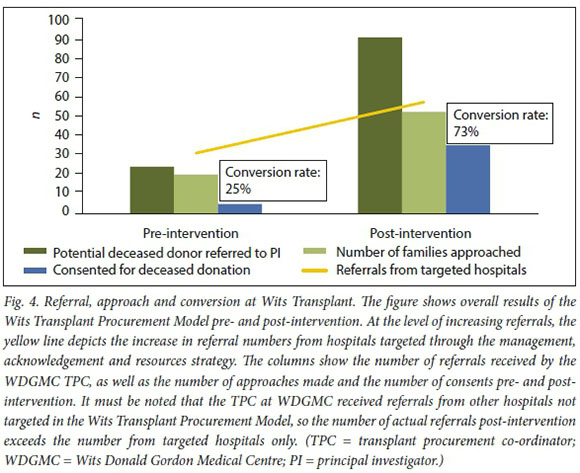

Preliminary results of the Wits Transplant Procurement Model

Since initiation of the Wits Transplant Procurement Model, both our referral numbers from targeted hospitals and our conversion rates have increased. Referrals from targeted hospitals increased by 54% (from 31 to 57). The PI's conversion rate increased from 25% (n=6) to 73% (n=35) after the initiation of Wits Transplant FACTS. Our referral, family approach and conversion rates are depicted in Fig. 4. Specific results of Wits Transplant FACTS are presented in Table 1.

It is notable that in 4 cases of no consent (8%) the family was initially approached by the doctor, who introduced the idea of organ donation, rather than the TPC. Also important is that during the intervention period, 18 potential donors who had been referred to the PI were subsequently found not to be brainstem dead according to the legal diagnostic pathway outlined in the National Health Act. This highlights the need for specialist skills to confirm brainstem death, and accessing these skills is a critical role of the TPC.

Of the families that did not consent, 7 cited cultural beliefs, and in 5 cases the family was not in agreement about whether the individual would have wanted to be an organ donor.

As the PI used the NHSBT-designed communication strategy in the unique SA setting, the approach was modified to account for unique situational factors (Fig. 5). Given the multilingual context of SA, an interpreter is introduced at the beginning of Wits Transplant FACTS when necessary. The communication process of asking for consent has been adapted to facilitate family discussion and negotiation, which is often relevant in SA because many families are large, and decision-making is seen as a collective effort. The 'donor pause', which is utilised by many SA TPCs, was added to the process, as was robust follow-up with the family and referring team after donation and transplantation has taken place.

The donor pause is an informal gathering in honour of the donor, and gives thanks for the family who made a lifesaving decision having just lost a loved one. The PI generally initiates two donor pauses, one at the bedside with the family, and the other in theatre before organ retrieval starts. The family are informed about the donor pause at the bedside, and invited to attend. The TPC will often recite a short poem, and this is followed by silent reflection or brief tributes.

Discussion

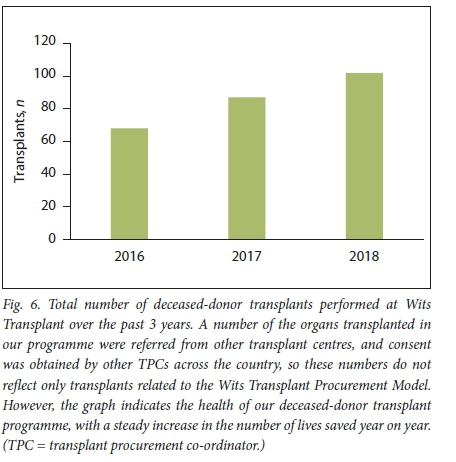

The overall success of the Wits Transplant Procurement Model cannot be attributed to any one of the initiatives we have put in place, but rather appears to be a function of the model in its entirety, which focused on increasing referrals and then ensuring that as many as possible are converted into family consents. Fig. 6 illustrates the increase in numbers of transplants from deceased donors at our centre from 2016, when the new model was envisaged. Some of these donors were consented at other centres, but the steady increase in the number of deceased-donor transplants is encouraging. Responses to certificates of appreciation and acknowledgment have been positive.

During the Wits Transplant FACTS intervention period, the PI almost trebled her conversion rate. The question of whether the treatment team, especially doctors, should approach patients is important. Through Wits Transplant FACTS, our TPC is equipped with a specific skill set that facilitates asking families for consent. The wording used, timing of the approach and substance of the conversation are all critical. While being time dependent, Wits Transplant FACTS also requires patience, and picking one's moment correctly. The treating team are not necessarily equipped to initiate an organ donor conversation or seek consent from a potential donor family. Furthermore, the treating team may not have the time required to follow Wits Transplant FACTS through to its conclusion, which can sometimes take several days. To this end, a substantial component of the Wits Transplant Procurement Model has been educating treating teams about the importance of allowing the TPC to initiate the concept of organ donation. It has also involved training treatment teams in how to introduce the TPC as part of the team, and the appropriate words to use.

The Wits Transplant Procurement Model is preliminary. It should be considered as a 'proof of concept', as it has only been implemented with one TPC at a single transplant centre. We hope that this model can be replicated with other TPCs at other transplant centres in SA, and that it may provide a way forward for increasing conversion rates across the country. In order to facilitate replication, we have produced a handbook that provides all practical details on the Wits Transplant Procurement Model and is available for download (http://www.dgmc.co.za/docs/Wits-Transplant-Procurement-Handbook.pdf).

The initial success of the Wits Transplant Procurement Model supports thinking that improving deceased-donor numbers must address donation at both referral and conversion levels. Furthermore, and perhaps more importantly, the success of the strategy may be due to its collaborative and inclusive nature. We aim to build trust, to be present and to make all stakeholders feel valued. We aspire to form relationships, to empathise with our families, who make the difficult donor decision under sometimes unimaginable circumstances, and to be humble in our dealings with all those healthcare professionals who help us save lives.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. The healthcare staff who refer potential donors, and the families who make the selfless decision to save lives through organ donation.

Author contributions. All authors contributed equally to aspects of the article including drafting, proofreading and final editing, and to the data collection and model development process.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Tager S, Etheredge HR, Fabian J, Botha JF. Reimagining liver transplantation in South Africa: A model for justice, equity and capacity building - the Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre experience. S Afr Med J 2019;109(2) :84-88. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMI.2019.v109i2.13835 [ Links ]

2. Matesanz R, Dominguez-Gil B, Coll E, et al. How Spain reached 40 deceased organ donors per million population. Am J Transplant 2017;17(6) :1447-1454. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt14104 [ Links ]

3. Chandler JA, Connors M, Holland G, Shemie SD. 'Effective' requesting: A scoping review of the literature on asking families to consent to organ and tissue donation. Transplantation 2017;101(5S):S1-S6. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000001695 [ Links ]

4. Soyama A, Eguchi S. The current status and future perspectives of organ donation in Japan: Learning from the systems in other countries. Surg Today 2016;46(4) :387-392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00595-015-1211-6 [ Links ]

5. Manyalich M, Istrate M, Paez G, et al Self-sufficiency in organ donation and transplantation. Transplantation 2018;102:S801. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.tp.0000543831.69729.e4 [ Links ]

6. Thomson D. Organ donation in South Africa - a call to action. South Afr J Crit Care 2017;33(2) :36-37. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAJCC.2017.v33i2.352 [ Links ]

7. Dominguez-Gil B, Murphy P, Procacdo F. Ten changes that could improve organ donation in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med 2016;42(2) :264-267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-015-3833-y [ Links ]

8. Ebadat A, Brown CV, Ali S, et al Improving organ donation rates by modifying the family approach process. J Trauma Acute Care Suig 2014;76(6): 1473-1475. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0b013e318265cdb9 [ Links ]

9. Weeks S, Ottmann S, Cameron A. Management of the multi-organ donor and logistic considerations. In: Higgins RS, Sanchez JA, eds. The Multi-Organ Donor: A Guide to Selection, Preservation and Procurement 3rd ed. United Arab Emirates: Bentham Books, 2018. [ Links ]

10. Etheredge H. Hey sister! Where's my kidney?' - exploring ethics and communication in organ transplantation in Gauteng, South Africa. http://wiredspace.wits.acza/bitstream/handle/10539/21425/Hey%20sister%20-%20where%27s%20my%20kidney.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y (accessed 20 July 2019). [ Links ]

11. Toubkin M. Status of transplantation in Gauteng Province. Presented at the Southern African Transplantation Society Congress, Durban, South Africa, 1-3 September 2017. [ Links ]

12. Etheredge H, Fabian J. Challenges in expanding access to dialysis in South Africa - expensive modalities, cost constraints and human rights. Healthcare 2017;5(3):38-50. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare5030038 [ Links ]

13. Moosa MR The state of kidney transplantation in South Africa. S Afr Med J 2019;109(4) :235-240. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2019.v109i4.13548 [ Links ]

14. Fabian J, Crymble K. End-of-life care and organ donation in South Africa - it's time for national policy to lead the way. S Afr Med J 2017;107(7) :545. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v107i7.12486 [ Links ]

15. Etheredge H, Penn C, Watermeyer J. Opt-in or opt-out to increase organ donation in South Africa? Appraising proposed strategies using an empirical ethics analysis. Dev World Bioeth 2018; 18(2): 119-125. https://doi.org/10.1111/dewb.12154 [ Links ]

16. Etheredge HR, Penn C, Watermeyer J. A qualitative analysis of South African health professionals' discussion on distrust and unwillingness to refer organ donors. Prog Transplant 2018;28(2): 163-169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1526924818765819 [ Links ]

17. Bhengu BR, Uys HH. Organ donation and transplantation within the Zulu culture. Curationis 200427(3):24-33. https://doi.org/10.4102/curationis.v27i3.995 [ Links ]

18. National Health Service Blood and Transplant Approaching the families of potential organ donors. 2015. http://odtnhs.uk/pdf/family_approach_best_practice_guide.pdf (accessed 20 July 2019). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

H.Etheredge

harriet.etheredge@mediclinic.co.za

Accepted 13 August 2019.