Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.109 no.8 Pretoria Ago. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2019.v109i8.14152

IN PRACTICE

MEDICINE AND THE LAW

Global injustice in sport: The Caster Semenya ordeal – prejudice, discrimination and racial bias

S MahomedI; A DhaiII

IBCom, LLB, LLM, PhD; Department of Jurisprudence, School of Law, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa

IIMB ChB, FCOG, LLM, PG Dip Int Res Ethics, PhD; Steve Biko Centre for Bioethics, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) requires the blood testosterone level of female athletes with differences of sex development to be reduced to below 5 nmol/L for a continuous period of at least 6 months, and thereafter to be maintained to below 5 nmol/L continuously for as long as the athlete wishes to remain eligible. Its ruling is based on questionable research findings. Medical decisions and interventions should be based on evidence from well-designed and well-conducted research and confirmatory studies. Caster Semenya, the reigning 800-meter Olympic champion since 2015, has challenged this ruling. Gender verification was instituted with women's participation in the Olympics in 1900, and female athletes were subjected to invasive, embarrassing and humiliating procedures. In its many decades of harsh scrutiny of successful female athletes, especially those from backgrounds similar to Semenya's, the IAAF has disrespected human rights and medical ethics and allowed prejudice, discrimination and injustice to infringe on their dignity and relentlessly obstruct their international sporting careers.

On 1 May 2019, the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) released its response to a challenge made to the International Association of Athletics Federation (IAAF)'s Eligibility Regulations for Female Classification for athletes with differences of sex development (DSD). It had found that the regulations were a necessary, reasonable and proportionate means of achieving the IAAF's legitimate aim of preserving the integrity of female athletics in the Restricted Events'.[1] The challenge had been instituted by Ms Mokgadi Caster Semenya, the reigning 800-meter Olympic champion since 2015.[2]

Ms Semenya, born on 7 January 1991 in Ga-Masehlong, a village near Polokwane, South Africa (SA),[3] challenged the IAAF's April 2018 rule change that required hyperandrogenous athletes to use medical interventions to lower their testosterone levels, from November of the same year. She claimed that the rules were unfair, discriminatory and potentially harmful. The scope of the rule change was limited to athletes competing over distances of 400 m, 800 m and 1 500 m,[1] and by inference, Ms Semenya, who also ran in 1 500 m events, was the target. Semenya was born a woman, identifies as a woman, and is regarded as a woman by family members, SA stakeholders, leaders, government and civil society.[4] Her life has been shaped by the sport that lifted her from rural poverty to the status of national icon and global celebrity.

This article describes the IAAF regulations, discusses gender verification in sport from a historical perspective, and considers the human rights and medical ethics violations that would result from the implementation of the regulations.

The IAAF DSD regulations

The regulations, which came into effect on 8 May, state that events from 400 m to the mile, including 400 m, hurdles races, 800 m, 1 500 m, 1-mile races and combined events over the same distances ('Restricted Events'), require any athletes who have DSD to meet certain criteria: the athlete is required to be recognised by law as

either female or intersex (or equivalent); her blood testosterone level must be reduced to below 5 nmol/L for a continuous period of at least 6 months; and thereafter her blood testosterone level must be maintained below 5 nmol/L continuously for as long as she wishes to remain eligible.[5] The IAAF claims that the regulations are necessary for competition to be fair and meaningful. Females with DSD have levels of circulating serum testosterone of 5 nmol/L or above, are androgen sensitive, have a subset of intersex variations, and do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies. Two days after the CAS ruling, Semenya won the women's 800 m race at the Diamond League event in Doha, Qatar.[6] This was the last race before the new testosterone rules were due to take effect. Semenya was left with having to make the harsh and painful choice of taking hormone therapy with its harmful side-effects or walking away from her life-defining sport. She chose to do neither and will be appealing the CAS ruling.

Notwithstanding the CAS panel's findings, its 165-page ruling expressed serious concerns with regard to whether the IAAF would be able to apply its DSD regulations fairly. In addition, it highlighted three challenging areas. Athletes would find it difficult to implement and comply with the DSD regulations because of the frequent need to take medications; there was an absence of concrete evidence to support the inclusion of certain events under the DSD regulations, including 1 500 m and 1 mile; and there was potential for harmful side-effects of the hormone medications for DSD athletes.[2] It is perplexing that the CAS panel allowed for the upholding of the regulations in the face of the serious concerns it raised.

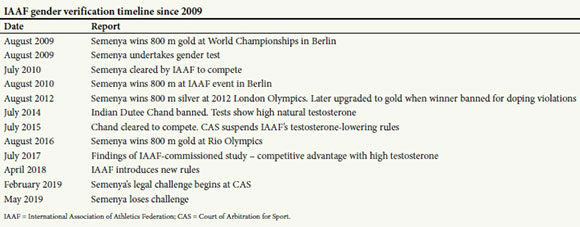

Semenya was 18 years old when she won the gold medal in the women's 800 m at the World Championships in Berlin in August 2009. Despite her winning time of 2 seconds slower than the world record, the IAAF on that same day requested that she undergo gender verification tests to determine her eligibility to compete in women's sport because of ambiguity with regard to her sex. According to reports, the tests were requested by the IAAF because of her deep voice, muscular build and rapid improvements in time. She was 7.5 seconds faster than her previous times during the win in Berlin. In July 2010, Semenya was cleared to compete by a panel of medical experts and in 2012 won the silver medal in the 800 m event at the Olympic Games in London.[4,7] The gold medal was won by a Russian athlete who was subsequently banned for doping. Semenya's silver medal was then upgraded to gold.

Gender verification in sport: A historical perspective

The Ancient Olympic Games began in 776 BC, and the first modern Olympics were in 1896.[8] Women's participation began in 1900. At that stage, international sports governing bodies such as the International Olympic Committee (IOC) executed measures to ensure that participants were undeniably female. This was because of emerging fears that some athletes were too masculine to be female. There were also concerns that men were masquerading as women to win medals.[4,9] Initially, female athletes were subjected to invasive, embarrassing and humiliating procedures and paraded nude before a panel of doctors who verified their sex. In 1968, the IOC introduced mandatory sex testing for women in sport. The mandatory aspect was terminated 30 years later, in 1998. Nevertheless, the IOC and other international sports bodies continued to implement gender verification and monitoring policies with regard to eligibility in female athletics competitions. The Barr body test was used until 1992. Because of its limitations, it was replaced by the polymerase chain reaction test of the SRY gene. However, false-positive results proved a limitation for this test, and by 2000, most international sports federations (24 out of 29) had abandoned routine gender verification testing.[4] At that stage the IOC instituted a policy granting authority to medical experts at international events to conduct gender verification should an athlete's sex be called to question. The IOC retained the right to test athletes where their gender identity was 'suspicious'. The IAAF's Policy on Gender Verification (2006) was similar to that of the IOC in that mandatory, standard or regular gender verification was no longer required.[4] In addition, the policy made it clear that gender issues could arise when an athlete or team brought a challenge against a competitor to the attention of authorities when suspicions were raised during an event; during the process of anti-doping controls; or when an athlete or her national federation communicated concerns. It was this 2006 policy that was in operation when the international uproar on Semenya broke out in 2009.[4] In April 2011, new rules from the IAAF came into force.[10] Where there were reasonable grounds, e.g. a complaint from a fellow athlete or a drug test anomaly, a confidential investigation to be handled by experts that would include whether the athlete was benefiting from elevated testosterone levels could be instituted. The athlete would be offered an effective therapeutic strategy to lower androgen levels where indicated. In 2015, there was a testosterone rule change after a challenge was brought to the CAS by Indian sprinter Dutee Chand, who had been withdrawn from the national team in 2014 and prevented from participating in the Commonwealth Games in Glasgow consequent to it being found that her natural testosterone concentrations were elevated to male levels.[11] The CAS ruling then found that evidence for testosterone increasing female athletic performance was lacking. The IAAF was given 2 years to provide such evidence. The IAAF's April 2018 rule change, which Semenya challenged at the CAS, was a response to the CAS 2015 ruling, as the IAAF had allegedly produced the evidence - a flawed and highly questionable study.[12,13] By powerfully policing gender boundaries, the IAAF and IOC have spent half a century resolutely trying to define who counts as a woman. The IAAF has now been trying to slow Semenya down for a full decade.

Human rights considerations

Several human rights concerns become apparent as a result of the IAAF regulations. The United Nations (UN) Human Rights Special Procedures issued an open letter to the IAAF[13] in which it highlighted contraventions of international human rights norms and standards, including:

• the right to equality and non-discrimination

• the right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health

• the right to physical and bodily integrity

• the right to freedom from torture, and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment and harmful practices.

The IAAF's regulation specifically targets women athletes who have DSD based on their natural physical traits, i.e. naturally occurring testosterone levels. It focuses on women who were assigned female gender at birth and whose social and legal identities are those of a woman. Moreover, it reinforces negative stereotypes and stigma. If it were not for the regulations, most women athletes with intersex traits might not even be aware of them. This discrimination interferes with their prospects of participating in the sports competition category in line with their gender, creates doubts about their sense of self, and erodes their rights to human dignity, privacy, health, freedom to make health-related choices, employment and livelihood. Suspicion, speculation and widespread surveillance of female athletes by scrutinising their perceived femininity are legitimised by these regulations. Risks to the women because of this discrimination include violence, ridicule, intrusion into their personal and private life, and other social harms. The IAAF has not applied similar regulations to male athletes, whose performance can also be influenced by natural and biological traits.[13] Tough male athletes who excel are applauded, whereas robust and resilient female athletes who excel have their abilities questioned and doubted.

Furthermore, there are a host of biological variations that offer specific competitive advantage. These include increased numbers of fast-twitch muscle fibres, exceptionally long limbs, extra-large hands and feet, and increased aerobic capacity.In addition, social and economic factors such as nutrition, access to specialist training facilities and coaching further enhance competitive gain.[13] Accordingly, the IAAF's notion of a level playing field in athletics is not only a delusion but could be perceived as deliberately deceptive. While naturally occurring testosterone may influence improved athletic performance, these other variables definitely come into play. Hence the degree and significance of advantage rendered by the former are dubious.

Racial and cultural bias resulting in prejudice and discrimination cannot be discounted. Semenya, a black woman from the global south, has a physique that differs from the traditional European archetype of femininity. This relentless scrutiny of the African female physique is not a new phenomenon and is aptly depicted by the exhibition of Saartjie Baartman, offensively termed 'the Hottentot Venus', who because of her large buttocks was exhibited as a freak show attraction in 19th century Europe.[14] When the new science of anthropology was initially advanced, colonial and imperial rule was often justified by anthropological research based on race categories where the native peoples of Africa and Asia were described as being of inferior intelligence and ability and hence in need of paternalistic rule by European powers.[15] The IAAF's regulation requiring Semenya and other women of similar backgrounds to change their bodies to compete is no different from the thinking of that time. It is paternalistic, clearly discriminatory and a substantial injustice at a global level. Several human rights instruments establish the right to equality and non-discrimination. These include the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,[16] the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights[17] and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.[18] These instruments also apply to sporting bodies that have a responsibility to respect international standards and ban discrimination in sport. It is ironical that one of the fundamental principles of the Olympic Movement[19] to which the IAAF belongs is that the practice of sport is a human right for every individual without discrimination.

Furthermore, the regulations contravene the UN Resolution on the Rights of Intersex Athletes,[20] which was released on 21 March this year by its Human Rights Council. The resolution condemns discrimination against women and girls born with variations in sex characteristics in the face of sport. The UN has called on governments to ensure that sports organisations 'refrain from developing and enforcing policies and practices that force, coerce and otherwise pressure women and girl athletes into undergoing unnecessary, humiliating and harmful medical procedures'. Such pressure could violate their rights to be free from cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, punishment or torture. Moreover, the right to bodily integrity, which allows for the control of all aspects of one's health, informed consent and autonomy, would also be transgressed. The IAAF regulations assert that there will be no pressure on athletes to undergo assessment and treatment. However, when the livelihood of athletes from the poorer regions of the world and their sporting careers are affected, they are not left with much choice but to undergo intrusive and medically unwarranted assessments and interventions with harmful side-effects, infringing on their rights to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health as affirmed in article 12 of the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.[17] Athletes like Semenya and Chand originate from and have grown up in challenging and mostly poor backgrounds. With discipline, skills and extreme effort they have managed to carve out sporting careers and a source of revenue for themselves.

Medical ethics

Human rights infringements as described above would be incompatible with medical ethics. In addition, medical decisions and interventions should be based on evidence from well-designed and well-conducted research. Evidence from confirmatory studies should also be available. The IAAF seems to be basing its arguments for regulating testosterone levels on a single scientifically questionable study. When valid scientific evidence is absent, benefits and harms cannot be conclusively ascertained. Therefore, artificially lowering endogenous testosterone in athletes must be considered unethical. This would be in line with Article 4 of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)'s Universal Declaration of Bioethics and Human Rights,[21] which establishes that 'In applying and advancing scientific knowledge, medical practice and associated technologies, direct and indirect benefits to patients, research participants and other affected individuals should be maximized and any possible harm to such individuals be minimized.'

The World Medical Association (WMA)'s Declaration of Geneva,[22] its International Code of Medical Ethics[23] and most country-level medical ethics codes place an obligation on doctors to act in the patient's best interest and uphold the highest standards of professional conduct, and not to allow their judgement to be influenced by unfair discrimination. The WMA Declaration on Principles of Health Care for Sports Medicine[24] obliges doctors to oppose or refuse to administer any interventions that are contrary to medical ethics and could be harmful to the athlete using them. This includes interventions that artificially modify blood constituents or biochemistry. Both the WMA[25] and the South African Medical Association[26] have condemned the IAAF regulations. The WMA has urged physicians globally not to implement the rules and to refrain from prescribing treatment for a condition that is not recognised as pathological.

In addition, the right not to be subjected to medical or scientific experiments without informed consent is protected by the UN Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights[17] and in SA by section 12(2) of the Bill of Rights,[27] where it is embodied as a non-derogable, fundamental right. If the IAAF is basing its decision to force medications on hyperandrogenous athletes on insufficient evidence, this forcing of treatment could in fact amount to unethical experimentation.

Conclusions

As Semenya goes back to the CAS to appeal its ruling, it is clear that her fight is more than just about testosterone. It is about all women like her who originate from disadvantaged and mostly poor backgrounds. Semenya is not a cheat - she has never been guilty of doping. She has naturally high levels of testosterone. She has a physique that differs from the traditional European archetype of femininity, but is considered normal in the global south. It is the IAAF that should be considered the cheat. In its many decades of harsh scrutiny of successful female athletes, especially those from backgrounds similar to Semenya's, it has disrespected human rights and medical ethics and allowed prejudice, discrimination and injustice to infringe on their dignity and relentlessly obstruct their international sporting careers.

Declaration. None

Acknowledgements. None

Author contributions. Equal contributions.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF). CAS upholds IAAF female eligibility regulations. https://www.iaaf.org/news/press-release/cas-female-eligibility-regulations (accessed 1 May 2019). [ Links ]

2. Ingle S. Semenya loses landmark legal case against IAAF over testosterone levels. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/sport/2019/may/01/caster-semenya-loses-landmark-legal-case-iaaf-athletics (accessed 1 May 2019). [ Links ]

3. South African history online. Mogadi Caster Semenya. https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/mokgadi-caster-semenya (accessed 1 May 2019). [ Links ]

4. Cooky C, Dworkin SL. Policing the boundaries of sex: A critical examination of gender verification and the Caster Semenya controversy. J Sex Res 2013;50(2):103-111. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.725488 [ Links ]

5. International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF). IAAF introduces new eligibility regulations for female classification. 26 April 2018. https://www.iaaf.org/news/press-release/eligibility-regulations-for-female-classifica (accessed 1 May 2019). [ Links ]

6. The Guardian. Actions speak louder than words: Caster Semenya defiant after Doha win - video. https://www.theguardian.com/sport/video/2019/may/04/actions-speak-louder-than-words-caster-semenya-defiant-after-doha-win-video (accessed 5 May 2019). [ Links ]

7. Wells C, Darnell SC. Caster Semenya, gender verification and the politics of fairness in an online track and field community. Sociol Sport J 2014;31(1):44-65. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2012-0173 [ Links ]

8. Penn Museum. The real story of the ancient Olympic Games. https://www.penn.museum/sites/olympics/olympicorigins.shtml (accessed 1 May 2019). [ Links ]

9. Slater M. Sport and gender: A history of bad science and 'biological racism'. https://www.bbc.com/sport/athletics/29446276 (accessed 5 May 2019). [ Links ]

10. International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF). IAAF to introduce eligibility rules for females with hyperandrogenism. 2011. https://www.iaaf.org/news/iaaf-news/iaaf-to-introduce-eligibility-rules-for-femal (accessed 1 May 2019). [ Links ]

11. Padawer R. Indian Dutee Chand set to run in the Olympics has been humiliated by sex testing. Sydney Morning Herald. 15 July 2016. https://www.smh.com.au/lifestyle/indian-dutee-chand-set-to-run-in-the-olympics-has-been-humiliated-by-sextesting-20160704-gpyeat.html (accessed 1 May 2019). [ Links ]

12. EWN. Sport scientist Ross Tucker previously said IAAF study is flawed. https://ewn.co.za/2019/02/19/sports-scientist-ross-tucker-previously-said-iaaf-study-is-flawed (accessed 1 May 2019). [ Links ]

13. United Nations Human Rights Special Procedures. Open letter to IAAF. https://www.sportsintegrityinitiative.com/un-urges-iaaf-to-withdraw-dsd-regulations/ (accessed 1 May 2019). [ Links ]

14. Holmes R. The Hottentot Venus: The Life and Death of Saartjie Baartman (Born 1789 - Buried 2002). London: Bloomsbury, 2008. [ Links ]

15. Briggle A, Mitcham C. Research Ethics 11: Science involving humans. In: Briggle A, Mitcham C, eds. Ethics and Science. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012:125-155. [ Links ]

16. United Nations. Universal Declaration of Human Rights. https://www.un.org/en/udhrbook/pdf/udhr_booklet_en_web.pdf (accessed 10 April 2019). [ Links ]

17. United Nations. International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. http://www.pwescr.org/PWESCR_Handbook_on_ESCR.pdf (accessed 6 April 2019). [ Links ]

18. United Nations. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/text/econvention.htm (accessed 10 April 2019). [ Links ]

19. International Olympic Committee. The Olympic Movement. https://www.olympic.org/the-ioc/leading-the-olympic-movement (accessed 30 April 2019). [ Links ]

20. United Nations Human Rights Council. Resolution on the Rights of Intersex Athletes. https://oiieurope.org/resolution-un-human-rights-council-women-girls-sport/ (accessed 1 May 2019). [ Links ]

21. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Universal Declaration of Bioethics and Human Rights. http://portaLunesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=31058&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html (accessed 30 April 2019). [ Links ]

22. World Medical Association. Declaration of Geneva. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-geneva/ (accessed 30 April 2019). [ Links ]

23. World Medical Association. International Code of Medical Ethics. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-international-code-of-medical-ethics/ (accessed 30 April 2019). [ Links ]

24. World Medical Association. Declaration on Principles of Health Care for Sports Medicine. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-on-principles-of-health-care-for-sports-medicine/ (accessed 30 April 2019). [ Links ]

25. World Medical Association. WMA urges physicians not to implement IAAF rules on classifying women athletes. https://www.wma.net/news-post/wma-urges-physicians-not-to-implement-iaaf-rules-on-classifying-women-athletes/ (accessed 30 April 2019). [ Links ]

26. South African Medical Association. SAMA support to Caster Semenya. https://www.samedical.org/cmsuploader/viewArticle/822 (accessed 30 April 2019). [ Links ]

27. South Africa. Bill of Rights of the Constitution of South Africa. http://www.justice.gov.za/legislation/constitution/SAConstitution-web-eng-02.pdf (accessed 30 April 2019). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

S Mahomed

mahoms1@unisa.ac.za

Accepted 20 May 2019.