Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.109 no.2 Pretoria feb. 2019

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2019.v109i2.13835

IN PRACTICE

HEALTHCARE DELIVERY

Reimagining liver transplantation in South Africa: A model for justice, equity and capacity building - the Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre experience

S TagerI; H R EtheredgeII; J FabianIII; J F BothaIV

IMB BCh, FCP (SA) Neurology; Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIPhD; Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre, Johannesburg, South Africa; Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIIMB BCh, FCP (SA), Cert Nephrology (SA); Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre, Johannesburg, South Africa; Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IVMB BCh, FCS (SA); Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre, Johannesburg, South Africa; Department of Surgery, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

The challenge of providing effective and integrated liver transplant services across South Africa's two socioeconomically disparate healthcare sectors has been faced by Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre (WDGMC) since 2004. WDGMC is a private academic hospital in Johannesburg and serves to supplement the specialist and subspecialist medical training provided by the University of the Witwatersrand. Over the past 14 years, our liver transplant programme has evolved from a sometimes fractured service into the largest-volume liver centre in sub-Saharan Africa. The growth of our programme has been the result of a number of innovative strategies tailored to the unique nature of transplant service provision. These include an employment model for doctors, a robust training and research programme, and a collaboration with the Gauteng Department of Health (GDoH) that allows us to provide liver transplantation to state sector patients and promotes equality. We have also encountered numerous challenges, and these continue, especially in our endeavour to make access to liver transplantation equitable but also an economically viable option for our hospital. In this article, we detail the liver transplant model at WDGMC, fully outlining the successes, challenges and innovations that have arisen through considering the provision of transplant services from a different perspective. We focus particularly on the collaboration with the GDoH, which is unique and may serve as a valuable source of information for others wishing to establish similar partnerships, especially as National Health Insurance comes into effect.

Scarcity of donor organs for transplantation is a problem worldwide, and South Africa (SA) is no exception. While donor scarcity here has been widely researched,[1,2] a lesser-known and often misunderstood phenomenon in SA is the challenge of providing effective and integrated transplant services across two socioeconomically disparate healthcare sectors.[3] Ideally, these services should be grounded within a framework that facilitates equal access to transplantation and optimises financial efficiency.

Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre (WDGMC) is a private academic hospital within the Faculty of Health Sciences teaching complex at the University of the Witwatersrand. The primary academic mandate of WDGMC is to facilitate the training of medical doctors in specialised and super-specialised disciplines. The state healthcare sector has limited capacity to provide advanced training across all specialties, and WDGMC functions in part to fill this gap.

One of the highlights of medical training and service provision at WDGMC is the liver transplant programme.[4] This programme is also unique in its service provision model, making liver transplantation available to state sector patients in SA through a private-public collaboration that promotes equality in accessing healthcare. Apart from Groote Schuur and Red Cross War Memorial Children's hospitals in Cape Town, WDGMC is the only centre in the country where state-based patients can access liver transplantation.[5] Our programme has evolved over time from a small, often fragmented and sometimes inefficient service into the largest-volume liver transplant programme in sub-Saharan Africa (Fig. 1). Measures to align transplant staff towards a collective and coherent vision have resulted in the strengthening of the programme. As a result, the programme now provides some transplant services that are unique on the continent, such as paediatric living-donor liver transplantation.

In this article we detail this model by focusing on the academic and service provision components that allow for more equitable access to liver transplantation. We begin with the history of the liver transplant programme, then overview the doctor employment model, which moves away from the traditional fee-for-service structure of private medicine in SA and promotes a coherent, goal-orientated transplant team with a strong emphasis on registrar and fellow training. We then discuss the liver transplant arrangement with the state health sector. This collaboration is particularly relevant at present, as such initiatives will form part of the framework for National Health Insurance in SA. Throughout, we highlight a number of successes and challenges encountered, and we hope to provide a blueprint for others who may wish to initiate similar programmes.

History of the liver transplant programme

The WDGMC liver transplant programme was inaugurated in 2004 through the joint efforts of the departments of Surgery and Anaesthesia at the University of the Witwatersrand. The intention was to establish liver transplantation within the Wits teaching portfolio, furthering opportunities for training and service provision in these areas. The need for a comprehensive liver transplant programme was acute. Statistics suggest that prior to the establishment of the WDGMC liver programme, fewer than 10 liver transplants were being performed annually in SA.[6] This was hardly sufficient to meet the needs of the country. Access was also inequitable, as most state sector patients were effectively excluded from liver transplantation, which was solely available in Cape Town, and in small volumes.

Shaping the liver transplant programme into its current form was not smooth sailing. After nearly 7 years, in 2011, the programme was facing collapse owing to poor surgical outcomes and inconsistent medical care. At this time, the programme relied on the services of part-time surgeons, either working in the state sector or in private practice, for many of whom transplantation was not a practice priority. Continuity of care, which is essential to good transplant outcomes,[7] was compromised, as part-time surgeons were performing transplant surgery but were not involved in the postoperative care of their patients. This would then fall to another doctor who was not necessarily familiar with the minutiae of the case. The structure of the existing hepatology service was a further limitation. It relied upon a single practitioner for medical care before, during and after transplantation, which was not sustainable. Analysis of the surgical and medical complications highlighted the need to develop a new, innovative model to take the liver transplant programme forward and improve outcomes.

WDGMC liver transplant programme staffing structure and human resources requirements

Liver transplantation is a relatively low-demand procedure that is highly resource-intensive. The human resources complement required to service the needs of the current liver transplant programme is large and diverse (Fig. 2). A range of medical specialists is needed, as in many other medical subdisciplines. However, transplantation differs in that it is necessary to employ two specialists in each subdiscipline, one to manage the donor aspect and the other to manage the recipient aspect. The pretransplant work-up for transplant listing and living donation is exhaustive and multidisciplinary. Recipients require extensive work-up and preparation for the transplant, which culminates in 'listing for transplant' with regular follow-up. Living donors also require extensive evaluation to determine their eligibility for donation with regular follow-up. Suitably qualified professionals are needed to undertake these tasks. At the time of the transplant, two teams are needed. One team is responsible for donor-related care and organ retrieval, while the second team takes care of implanting the organ into the recipient. This requires duplication not only in terms of human resources, but also infrastructure - for example, two fully equipped operating theatres running simultaneously and two postoperative intensive care unit (ICU) beds.

Doctor employment model

In 2012, restructuring the programme to create surgical and medical positions for salaried doctors led to the establishment of the first fixed-salary doctor employment model of this kind in the private health sector in SA. Doctors are employed as either full-time or part-time service providers. This model allowed us to recruit an SA-born, internationally trained transplant surgeon to lead our programme. It also facilitated the creation of a truly multidisciplinary team for the provision of comprehensive care across the transplant spectrum, positioning WDGMC as a national referral centre for the management of children and adults with acute and chronic liver failure. The fixed-salary model removed private sector remuneration incentives where income is reliant on high patient throughput. This arrangement allows our specialists to dedicate time to providing a thorough teaching platform for registrar and fellow training in liver transplantation, as well as promoting a strong research trajectory for the programme. Today, the programme offers subspecialist training in adult and paediatric hepatology, transplant surgery and critical care. Over the past 6 years, the programme has produced four transplant surgeons, two adult hepatologists and one paediatric hepatologist, all of whom have been funded by WDGMC, through a mechanism that channels day-to-day profits of the hospital back into training.

Surgeons have bought into this model because it allows them to pursue transplant surgery as a career, which would not be possible under a fee-for-service structure where patient throughput may be low. Moreover, the unpredictable nature of organ transplantation, which is dictated by organ availability, and the time constraints for removal and implantation of organs make it impossible to run a surgical private practice while trying to pursue a career in transplant surgery.

All salaried doctors are employed via the Wits Health Consortium (WHC). The WHC is a wholly owned subsidiary of Wits University and is permitted to employ doctors under certain circumstances by the Health Professions Council of South Africa. These doctors are then seconded to WDGMC.

Cost recovery

Patients on medical aid are billed under a group practice number per discipline, in line with Board of Health Care Funders requirements. Fees collected from this billing are used to offset the doctors' salaries and cover approximately 50% of the transplant surgeon salary bill, with the other 50% funded by WDGMC. A large number of surgeons are required to extract organs (from deceased and living donors) and perform split-liver and living-donor liver transplants. This necessitates subsidisation of salaries.

Innovation

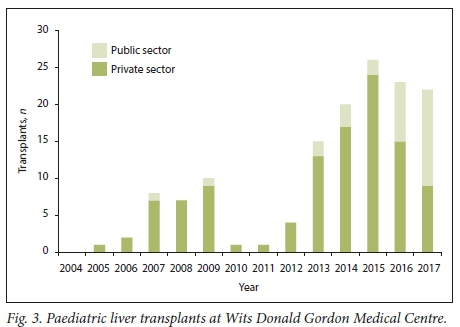

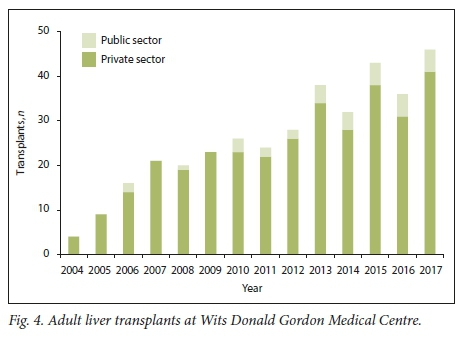

The fixed-salary employment model has also promoted innovation, led by specialists who are mandated to focus solely on providing transplant services. This innovation is epitomised by the creation of the only living-donor paediatric liver transplant programme in sub-Saharan Africa. This programme has had a number of successes, the most ground-breaking of which was the first living-donor liver transplant from an HIV-positive donor to an HIV-negative recipient in the world, in 2017.[8] Other innovations include expanding transplant services for previously contraindicated conditions including non-resectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma and non-resectable colorectal liver metastases. Through these and other initiatives, the number of liver transplants per year has increased from less than 10 to over 70 (Figs 3 and 4).

Infrastructure

Establishing the liver transplant programme required the construction of a dedicated laminar flow operating theatre large enough to accommodate the entire liver transplant process from donor extraction to implantation. This can involve the services of up to 20 staff in theatre at the same time. Growth in the programme, particularly the implementation of living-donor liver transplantation, demanded more theatre space. The extension and upgrade of an existing theatre created a second large laminar flow space to accommodate the donor and recipient procedures in quick succession. In 2018, we began construction of a dedicated transplant wing, with a closed transplant ICU and paediatric transplant ward to accommodate expanding numbers in the programme. The new wing will be opening in early 2019.

Access and equality - collaboration with the state health sector

Access to healthcare services in SA is known to be disparate across the two healthcare sectors, with private patients often accessing a wider range of services than state patients. A main objective of the WDGMC liver transplant programme is to make the service equally accessible to state and private patients. We have made significant progress in achieving this vision through an arrangement with the Gauteng Department of Health (GDoH). However, this would ideally be formalised as an official public-private partnership (PPP), which we are still working towards.

What is a PPP?

The South African National Treasury defines a PPP as: '... a contract between a public sector institution/municipality and a private party, in which the private party assumes substantial financial, technical and operational risk in the design, financing, building and operation of a project'.[9]

There are two main types of PPP:

1. The private party performs an institutional/municipal function.

2. The private party acquires the use of state/municipal property for its own commercial purposes.

A PPP can also be a hybrid of these two formats. For all these formats, payment should occur via one of two mechanisms: either the state institution pays the private party for the services delivered, or the private party collects fees from users of the service. A combination of these reimbursement models can also be considered. The National Treasury PPP programme further emphasises that a PPP is not any of the following:

• It is not simply outsourcing of a function where substantial financial, technical and operational risk is retained by the public institution.

• It is not a donation by a private party for public good.

• It is not the commercialisation of a public function by the creation of a state-owned enterprise.

• A PPP does not constitute borrowing by the state.

PPPs for healthcare provision in Africa are recognised as beneficial through their capacity to provide access to quality care in a cost-effective way.[10] However, strong leadership is needed to ensure their success, as these collaborations are unfamiliar to many who will be required to implement them at policy and hospital management level. For a truly integrated PPP to work long term, the partnership requires leadership commitment and a common vision.

Evolution of the WDGMC liver transplant PPP

Discussions pertaining to the establishment of a PPP for provision of liver transplantation to state patients through the WDGMC transplant programme were initiated in 2008 and have been ongoing to a greater or lesser extent since then. In 2013, a set global fee, charged to the GDoH for each liver transplant in a state patient, was initiated. This framework forms the basis for a PPP as envisioned by government and defined under point 1 above, as WDGMC has taken on significant financial, technical and operational risk in order to realise its commitment to the arrangement. While this collaboration has brought life-saving liver transplantation to public sector patients who would otherwise have died, there are a number of shortcomings to the current model that need to be addressed to ensure sustainability of liver transplant provision to state patients.

Main challenges of the liver transplant arrangement

The primary negotiations geared towards establishing a formal liver transplant PPP occurred at a clinician level, between public sector clinicians and the incumbent politicians in the GDoH at the time.

The global fee was calculated with limited information, which was not verified by WDGMC, resulting in a flawed financial model that excluded many critical stakeholders and service providers and was not responsive to price fluctuations. A further limitation was an assumption that transplant services could be provided to state patients, at a private site, using a combination of private and state clinicians (surgeons, anaesthetists and physicians) as well as a combination of private and state service providers (laboratories, radiology). This model of service provision was not sustainable in the clinical, laboratory or radiological environment. A critical shortage of specialist and subspecialist clinicians, the 'brain drain and inefficiencies in the National Health Laboratory Service soon manifested themselves in highlighting the dramatic inadequacies of the financial compensation model.

In addition, a written agreement between WDGMC and the GDoH, which could formalise the arrangement as a PPP, was never signed when the 2008 - 2011 negotiations concluded. Shortly thereafter, a change in political appointees occurred in the GDoH, leaving WDGMC with a commitment to the collaboration but without a signed agreement. This continues to render renegotiation of the financial arrangement intensely frustrating, as there is no documented framework for its basis, while WDGMC upholds its end of the partnership in good faith.

The financial woes of the GDoH have further compounded the tenuous financial arrangement for liver transplant provision to state patients. Lack of leverage for negotiation has left WDGMC with a suboptimal global fee that is now 10 years old and has not been increased within that period, even to account for inflation. The financial impact on WDGMC has increased with the increase in numbers of liver transplants for state patients, and this upward trajectory continues. The global fee does not include reimbursement for surgical services, further necessitating the subsidisation of surgical salaries when transplanting state sector patients. The limitations of the current financial model are evidenced by the figures. Less than a third of the actual cost of doing a transplant on a state patient is recovered through the global fee - WDGMC subsidises 70% of the cost. For the 2017 financial year, this amount was in excess of ZAR10 million.

The WDGMC shareholders have tolerated this situation for the greater good brought about by this unique programme, but it must be recognised that the WDGMC financial resources now directed towards subsidising transplants for state patients would otherwise be deployed in specialist and subspecialist training, and that the resources available to us need to be allocated equally across all the medical disciplines we support. In order to ensure the ongoing provision of liver transplantation to state patients, a more realistic financial model needs to be negotiated. Ideally this would cover substantially greater costs of transplant work-up, surgical intervention, postoperative and post-transplant care for state sector patients, but some components will still be subsidised by WDGMC.

Benefits of the liver transplant arrangement

The vision was to create equitable access to liver transplantation across both healthcare sectors. This has been achieved despite the challenges of the arrangement in its current form. A single listing process, where state and private patients are maintained on the same waiting list, ensures allocation of donor livers based on clinical need irrespective of payer category. This has resulted in an increase in the proportion of state patients wait-listed for liver transplantation (currently the paediatric list comprises 50% state patients, while the overall proportion of state patients for adults and paediatrics is 30%).

The absolute numbers of state patients we transplant through the PPP is still limited owing to inefficient referral and work-up in the state sector, an issue we are trying to address through raising awareness and creating stronger partnerships with referral centres.

Service provision structure of the liver transplant arrangement

The service provision structure is built on a three-phase process (Fig. 5) that aims to maximise resource efficiency across both health sectors in the best interests of patients. The process utilises state sector services where these are available, supplemented by private services provided at WDGMC where they are not.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, the model developed at WDGMC for the provision of liver transplantation is a first for SA. By detailing how it was achieved, this article will assist those who wish to establish specialist medical interventions at their hospitals, with an emphasis on equity in access, social accountability, training and research, and preferably to do so without encountering some of the pitfalls that we have met over the years. It goes without saying that no two such programmes will be the same, and it is likely that everyone will make mistakes along the way. Nonetheless, we hope that the main successes of our experience - for instance the fixed-salary model and partnership with the state sector - will be replicable in other settings. In spite of some of our challenges, it is noteworthy that those working in our transplant programme generally feel that the clinician relationships across disciplines and sectors are good, and that a sense of coherence and collective efficacy prevails.

Declaration. None.

Acknowledgements. None.

Author contributions. ST: wrote first draft, input on all subsequent drafts; HRE: input on drafts, editing, figures; JF: input on drafts, editing, figures; JB:input on drafts, editing.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Chandler JA, Connors M, Holland G, Shemie SD. 'Effective requesting. A scoping review of the literature on asking families to consent to organ and tissue donation. Transplantation 2017,101(5S).S1-S16. https://doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000001695 [ Links ]

2. Etheredge HR, Turner R Kahn D. Public attitudes to organ donation among a sample of urban-dwelling South African adults. A 2012 study. Clin Transplant 2013,7(5).684-692. https://doi.org/10.1111/ctr.12200 [ Links ]

3. Etheredge HR, Fabian J. Challenges in expanding access to dialysis in South Africa - expensive modalities, cost constraints and human rights. Healthcare 2017,5(3).E38. https://doi.org/10.3390/health care5030038 [ Links ]

4. Song E, Fabian J, Boshoff PE, et al. Adult liver transplantation in Johannesburg South Africa (2004 - 2016). Balancing good outcomes, constrained resources and limited donors. S Afr Med J 201S108(ll)»29-936. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2018.vl08ill.13286 [ Links ]

5. Organ Donor Foundation of South Africa. Transplant centres 2017. https://www.odf.orgza/info-and-faq-s/transplant-centers.html (accessed 4 December 2018). [ Links ]

6. Organ Donor Foundation of South Africa. Transplant statistics 2016. https://www.odf.orgza/info-and-faq-s/statistics.html (accessed 4 December 2018). [ Links ]

7. Etheredge HR Penn C, Watermeyer J. Interprofessional communication in organ transplantation in Gauteng Province, South Africa. S Afr Med J 2017,107(7):615-620. https://doi.org/10.7196/samj.2017.vl07i7.12355 [ Links ]

8. Botha J, Conradie F, Etheredge H, et al. Living donor liver transplant from an HIV-positive mother to her HIV-negative child, opening up new therapeutic options. AIDS 2018,32(16).F13-F19. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0000000000002000 [ Links ]

9. South African National Treasury. National Treausry PPP Manual 2004. http://www.ppp.gov.za/Legal%20Aspects/PPP%20Manual/Module%2001.pdf (accessed 4 December 2018). [ Links ]

10. Marek Τ, OTarrell C, Yamamoto C, Zable I. Trends and opportunities in public-private partnerships to improve health service delivery in Africa. 2005. World Bank Africa Region Human Development Working Paper Series. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/480361468008714070/pdf/3364r:0AFROHDwp931healthlservice.pdf (accessed 4 December 2018). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

J Fabian

june.fabian@mweb.co.za

Accepted 10 December 2018