Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.108 n.10 Pretoria Oct. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2018.v108i10.13052

RESEARCH

'Going the extra mile': Supervisors' perspectives on what makes a 'good' intern

M de VilliersI; B van HeerdenII; S van SchalkwykIII

IMB ChB, MFamMed, FCFP (SA), PhD; Division of Family Medicine and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa

IIMB ChB, MSc, MMed (Int); MB ChB Unit, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa

IIIBA, BA Hons, MPhil, PhD; Centre for Health Professions Education, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Much has been published on whether newly graduated doctors are ready for practice, seeking to understand how to better prepare graduates for the workplace. Most studies focus on undergraduate education as preparation for internship by investigating knowledge and skills in relation to clinical proficiencies. The conversion from medical student to internship, however, is influenced not only by medical competencies, but also by personal characteristics and organisational skills. Most research focuses largely on the interns' own perceptions of their preparation. Supervisors who work closely with interns could therefore present alternative perspectives.

OBJECTIVES. To explore the views of medical intern supervisors on the internship training context, as well as their perspectives on attributes that would help an intern to function optimally in the public health sector in South Africa (SA). This article intends to extend our current understanding of what contributes to a successful internship by including the views of internship supervisors.

METHODS. Twenty-seven semi-structured interviews were held with medical intern supervisors in 7 of the 9 provinces of SA. The data were thematically analysed and reported using an existing framework, the Work Readiness Scale.

RESULTS. The intern supervisors indicated that interns were challenged by the transition from student to doctor, having to adapt to a new environment, work long hours and deal with a large workload. Clinical competencies, as well as attributes related to organisational acumen, social intelligence and personal characteristics, were identified as being important to prepare interns for the workplace. Diligence, reliability, self-discipline and a willingness to work ('go the extra mile') emerged as key for a 'good' intern. The importance of organisational skills such as triage, prioritisation and participation was foregrounded, as were social skills such as teamwork and adaptability.

CONCLUSIONS. This article contributes to our understanding of what makes a successful medical internship by exploring the previously uncanvassed views of intern supervisors who are working at the coalface in the public health sector. It is envisaged that this work will stimulate debate among the medical fraternity on how best to prepare interns for the realities of the workplace. Educational institutions, health services and interns themselves need to take ownership of how to instil, develop and support these important attributes.

Are new doctors prepared for internship? While successful graduation suggests that they have the requisite clinical competence, we could question the extent to which this positions them to be 'good' interns. Much has been published in the international literature on whether newly graduated doctors are ready for practice, seeking to understand how to better prepare graduates for the workplace.[1] In South Africa (SA), several studies have explored this issue.[2-7] Ninety-one percent of interns in a cohort study indicated that they were able to cope with internship, suggesting that they were sufficiently prepared for its demands.[2] Generally, medical graduates thought that they had been well prepared for most mainstream clinical activities, but acknowledged that they were less well prepared in some areas, such as pharmacology, medicolegal work and non-clinical roles in internship.[3] In terms of procedures, interns again felt confident to perform most of these, but did not feel ready to perform circumcisions, episiotomies, appendectomies and assisted deliveries.[4,5] Despite most interns feeling well prepared, critical gaps in paediatrics, orthopaedics and obstetrics have been identified, as well as a need for additional training in ophthalmology, dermatology and otorhinolaryngology.[6,7] All these studies have made recommendations regarding a change in curricula and approaches to improve medical graduates' readiness for practice.

There are two gaps in this research. Firstly, while it is known that the conversion to internship is influenced not only by clinical competencies but also by other aspects, such as personal characteristics and organisational skills,[8] studies focusing on undergraduate education as preparation for internship investigate mostly knowledge and skills in relation to clinical proficiencies.[1,9] Furthermore, the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) approved core competencies for a medical student on the threshold of internship. These include, in addition to the role of healthcare practitioner, roles as a professional, communicator, collaborator, leader and manager, health advocate and scholar.[10,11] It is important to determine how new interns perform in terms of this broader set of competencies. Secondly, most studies focus largely on the interns' own perceptions of their preparation. The views of other stakeholders may provide alternative perspectives.[1,3] Intern supervisors, registered medical practitioners with at least 3 years' experience in a particular clinical domain, work closely with interns and are therefore in a good position to perhaps present such alternative views.[12]

The challenges facing medical graduates when entering internship have been well described in the SAMJ.[2,12,13]These include long hours of work, heavy workload, limited supervision and stress. In 2017, there were 3 796 medical intern posts in public healthcare facilities accredited by the HPCSA (HPCSA - personal communication, 27 June 2017). Rotations ranging from 1 to 4 months in 8 clinical domains are completed during internship.[14,15] Medical internship in SA is thus a fairly extensive enterprise, in which high stakes are involved for many role players. The aim of this study was to explore the views of a subset of these role players, the medical intern supervisors, on the internship training context as well as their perspectives on attributes that would help an intern to function optimally in the public health sector in SA. This article intends to extend our current understanding of what contributes to a successful internship by including the views of internship supervisors.

Methods

This study was nested within in a 5-year longitudinal cohort study that investigated the establishment of the Ukwanda Rural Clinical School (URCS) at Stellenbosch University and its effect on various role players, including graduates, interns, intern supervisors and the community.[16] The intern supervisor study set out to explore the nature of the internship training context and what supervisors would perceive as a good intern. The overarching longitudinal study was set in an interpretive paradigm.[17] For the intern supervisors, the researchers similarly used an explorative approach. The author team consisted of a family physician, a medical training programme director and an educationalist. None of the authors knew the intern supervisors who participated in the study.

Purposive sampling was done. Sites where there were medical graduates in their first year of internship, who had completed their final year at URCS, were selected based on location to ensure a spread across SA. All of the URCS graduates at these sites were invited to participate. In addition, graduates who had followed the traditional final-year rotation at the tertiary hospital, and who were completing their internship at the same selected sites, were invited to participate. All those who agreed were interviewed. The clinical supervisors for these interns formed the sample for this study. The intern supervisors also supervised interns who qualified from other universities.

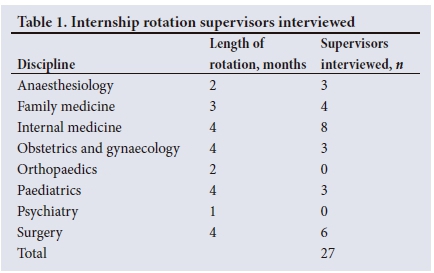

Fourteen semi-structured interviews were conducted with intern supervisors in 2014 and 13 in 2015; 10 supervisors were female and 17 were male. On average, they supervised groups of 8 interns (range 1 - 15), who had graduated from a number of different universities. The intern supervisors had an average of 7.5 years' experience of supervising interns (range 1 - 30 years). The supervisors comprised heads of department, consultants, a clinical manager, registrars, medical officers and a community service doctor. These supervisors were based at 15 hospitals in 7 of the 9 provinces of SA, which represented a range of HPCSA-accredited intern training facilities from large central academic hospitals to smaller regional health facilities, some in semi-rural areas. The intern supervisors worked in 6 of the 8 intern rotation domains (Table 1).

In most cases, face-to-face interviews were conducted in English with intern supervisors at hospitals where the interns were working. Telephonic interviews were held when the individual was not available in person during the time that the interviewer visited the particular site. The interviews were conducted by a trained independent interviewer, were of 30 - 60 minutes' duration and were audio recorded and transcribed.

Thematic analysis was conducted following the 6 steps described by Braun and Clarke.[18] The authors read the interviews several times to familiarise themselves with the data. Initial manual coding was done, adding codes that would allow key points in the data to be gathered. Notes were then compared and similar codes were grouped into categories and themes by reaching consensus through discussion. During the iterative analysis regarding what comprises a good intern, attempts to organise the data proved complex, as there were overlaps and the categories lent themselves to differing individual interpretations. Therefore, an existing framework, i.e. the Work Readiness Scale (WRS), as developed by Caballero et al [19] and applied to the health professions by Walker et al.,[20] was identified to organise the categories in the results relating to the attributes of a good intern. Illustrative quotes were identified from the data.

Ethical approval was obtained from Stellenbosch University's Health Research Ethics Committee (ref. no. HREC N12/03/014). The intern supervisors signed written informed consent forms.

Results

The results are reported according to two overarching foci, i.e. (i) the context of internship training; and (ii) what comprises a good intern within this context.

The context of internship training

The intern supervisors believed that some of the first-year interns experienced the transition from student to doctor as challenging. The interns had to apply theory to practice, take personal responsibility for patient care and adapt to a new environment. They also had to work long hours and deal with a heavy workload. The supervisors alluded to factors that helped to enhance preparedness to deal with these challenges.

Transition from student to doctor

The intern supervisors (interviewees) described the transition from student to doctor as the most significant challenge for first-year interns, as they had to apply their theoretical knowledge in clinical practice. One of them described it as follows: 'I think the transition for them is actually going from actually being a student and looking at the books and learning the knowledge that they've got, to actually going to a patient and actually taking responsibility for assessing and managing a patient' (IS_WR02_2015).

In addition, assuming personal responsibility for patient care for the first time proved to be demanding, a realisation reflected on as follows: 'The most difficult thing is now you are on your own. You know you are an intern and you are supposed to work under supervision, but there are some decisions you need to make. As a student, I don't want to use that word, who cares? The responsibility is not on you. If you don't do well, the patient is going to die. It's scary somehow' (IS_WR04_2015).

The supervisors indicated that more hands-on clinical experience and responsibility for patients as part of a team during undergraduate training helped interns to overcome this transition: 'I think ones where their undergraduate programme puts more focus on them actually running their own patients and being more part of the unit as opposed to just attending tutorials and that sort of thing, and where they are really made to be part of the unit and they have to take responsibility' (IS_TGB01_2014).

Dealing with the heavy workload and long hours

The interviewees identified the heavy workload and long working hours as difficult for the new interns. They felt, however, that these were the realities of the health services that the interns had to learn to cope with: 'They have got to master the art of working for long hours, sustaining their attention for very long hours' (IS_LIM01_2015).

The supervisors were of the opinion that working on call during undergraduate training assisted with internship preparation: 'Probably calls, because I know some universities do expect quite a lot of after-hour work, but in general students don't have to do the same amount of like hours of lack of sleep. So I think in general the transition from being a student to being an intern, it's really the hours of work' (IS_TGB04_2015).

Adjusting to a new environment

Adjusting to a different health service from where they had been trained, relocating to a new community and making new friends were also difficult for interns, according to the interviewees. Language and cultural differences and getting to know the healthcare team in the new working environment took time to adjust to: 'I think the hardest part is that they have to be used to be doing clinical medicine rather, and to most of them it's a foreign hospital, because we're not always here for their clinical teaching. So the problem is getting used to that' (IS_WR05_2015).

The supervisors thought that being exposed to role models and building resilience were factors that were helpful in preparing interns for the world of work: 'So if you have a role model that makes you do that as a young doctor, you are at another level altogether' (IS_ TGB03_2015). 'So in other words resilience ... maybe actually giving interns quite regular support. In the sense of coaching or groups that are physically there for the interns, where they can be briefed and they can actually feedback on their problems' (IS_WR02_2015).

What comprises a good intern?

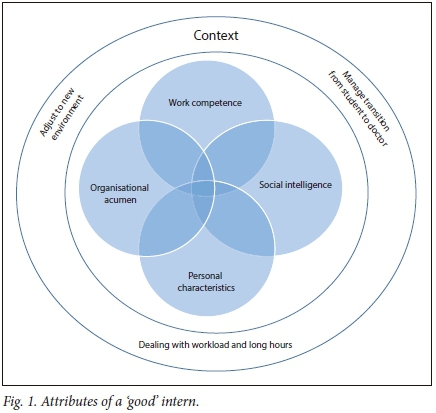

During the interviews, the concept of a good intern was explored. A good intern was seen as someone who could work well within the described internship training context and contribute to safe patient care. The categories generated during the initial coding process were mapped against the WRS.[19,20] The results are reported here using the WRS components, i.e. work competence, organisational acumen, social intelligence and personal characteristics.[20]

Work competence

Work competence is described as the technical knowledge and skills needed to perform the job at hand, such as technical focus, problemsolving skills, clinical skills, motivation, confidence, responsibility and knowing one's limitations.[19,20]Table 2 lists the categories related to work competence mentioned by the intern supervisors, including short illustrative quotes and the interview sources.

Organisational acumen

Organisational acumen is described as comprising aspects such as work ethic, knowledge of the working environment (ward, hospital), maturity, organisational awareness and professional development.[19,20] The intern supervisors foregrounded the importance of organisational acumen for a successful intern: 'A good intern has to have very good organisational and people management skills. They have to be able to get the job done, under pressure, and they have to be able to approach their job list in a rational manner. They have to be able to prioritise what needs to be done urgently and what can wait, and they have to have good organisational skills' (IS_WR01_2015). Table 3 lists these categories from the data, including illustrative quotes and interview sources.

Social intelligence

The social intelligence domain is described as including teamwork, the ability to communicate with a range of coworkers and clients, interpersonal adaptability and conflict management, and asking for help.[19,20]Table 4 lists these categories, including relevant quotes from the data and interview sources.

Personal characteristics

The personal characteristics domain is deemed to include personal skills, self-knowledge, flexibility, resilience and adaptability.[19,20] The intern supervisors indicated that each individual intern came with their own set of characteristics: 'Obviously some people, personalities play a role' (IS_TGB04_2015).

For the intern supervisors, the most important attribute of an intern was to be conscientious. A supervisor described this as follows:

'For me, a good intern, it's not a student that has got straight As from medicine. A good intern is an average guy in medical school, but it is an intern that is conscientious about patient care. For me that is a good intern ... And of course the good intern is the one that shows up for work on time, and leaves whenever it's appropriate to do so' (IS_TGB03_2015). Table 5 lists these categories, including quotes from the data and the interview sources.

Fig. 1 demonstrates the interconnectedness between the contextual factors in internship and the attributes needed for an intern to be able to function within this environment.

Discussion

This study provides insight into the context awaiting interns on entering the workplace, i.e. long hours of work, heavy workload and taking on responsibilities. These factors have been described before.[2] Work environment stressors such as the fast pace of work, poor supervision, work-life balance challenges and constant rotations have also been reported as facing new graduate doctors in Kenya,[21] Australia[22] and elsewhere.[1] In the current study, the ability to adapt to these realities is foregrounded as a crucial attribute for junior doctors. Support for interns helped them to build resilience and to cope with the demands of their first year of internship. Being able to ask for help and knowing how to access support in difficult circumstances are important factors in developing resilience in healthcare workers.[20]

The ability to function as a competent healthcare practitioner, described under work competence in our results, is still key to being a good intern. In addition to the medical technical focus, important attributes include critical thinking and problem-solving.[19] This study further underlines the importance of the other three work-readiness domains of organisational acumen, social intelligence and personal characteristics in preparing interns for the workplace.

Willingness to work or 'going the extra mile' emerged as a key attribute of a good intern, as expressed in the following quote from supervisor WR03_2014: 'He was really good. He was very enthusiastic. He is quiet and reserved, but he was very diligent and always went the extra mile and we were all very happy with him.' Personal characteristics such as diligence, reliability, dependability, self-discipline and thoroughness were mentioned. In the literature, these have been grouped together under the term 'conscientiousness', which is one of the so-called 'Big Five' primary factors that underlie personality.[23] Research further points out that conscientiousness is positively associated with performance in the workplace,[24] as well as being positively correlated with preparedness for internship.[25] These characteristics can be developed during undergraduate training of medical students through exposure to discipline, diligence and positive role modelling. Moreover, so-called character virtues such as duty, commitment, maturity and resilience are important elements of professionalism that can be regarded as being closely aligned with the dimensions of conscientiousness described above.[26]

Of note is that the word 'commitment' is central to the phrasing of all three key competencies under 'Professional role' in the HPCSA framework.[10] Enabling competencies include 'appropriate professional behaviour, including honesty, integrity, commitment, compassion, respect for life, accessibility and altruism'. It could be argued that the term commitment perhaps aims to encompass the conscientiousness and duty principles as foregrounded by the results of this study. It is, however, recommended that the specific conscientiousness characteristics be explicitly listed in the competency framework to guide preparation for internship.

A second area of importance emerging from this study, which appears to be lacking from the HPCSA key competency framework, is that of organisational abilities, such as being able to triage, prioritise, take initiative and make sound decisions. Our study and other studies found these so-called non-technical skills to be important for interns entering practice.[27] Sein and Tumbo[28] indicated that attitude, personality and interpersonal skills were essential to overcome internship challenges.[28] More research on these 'peripheral' factors is needed to understand how best to create opportunities for medical students to enhance these skills during undergraduate training, as well as in the support and development of new interns in the workplace.

Study limitations

The transferability of the findings of this study may be limited, as it was restricted to intern supervisors in the SA public healthcare sector. Although the sample was small, it represented 7 of the 9 provinces in the country and therefore drew on potentially quite different settings. The sampling strategy (following interns who had graduated from one university) could also be a limitation; however, all the supervisors were supervising interns from a number of different universities at the time. The findings could have benefited from a validation of the data back to the supervisors, but that proved logistically challenging.

Conclusion

This article contributes to the literature by exploring the previously uncanvassed views of intern supervisors, who are working at the coalface in the public health sector, on what makes a good intern -being fully committed to good patient care. In addition to clinical work competencies, attributes related to organisational acumen, social intelligence and personal characteristics that helped medical interns to function within the internship training context were identified. It is hoped that this can stimulate debate in the medical fraternity on how best to prepare interns for the realities of the workplace and perhaps be more explicitly included in the competency frameworks of training institutions and the HPCSA. Educational institutions, health services and interns need to take ownership of how to instil, develop and support these key attributes.

Acknowledgements. Norma Kok, who did the interviews; the intern supervisors, who gave their time for the interviews; Stellenbosch University Rural Medical Education Partnership Initiative (SURMEPI), under whose auspices the research was done; and the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) for funding the research.

Author contributions. SvS: principal investigator of the overarching 5-year longitudinal study; BvH and MdV: analysed the intern supervisor interviews (BvH the 2014 dataset and MdV the 2015 dataset); SvS: assisted with the thematic analysis of the data; MdV: wrote the manuscript; and SvS and BvH: contributed to the manuscript through several iterations and approved the final version.

Funding. The study was funded by the President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through Human Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) under the terms of T84HA21652.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Cameron A, Millar J, Szmidt N, Hanlon K, Cleland J. Can new doctors be prepared for practice? A review. Clin Teach 2014;11(3):188-192. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.12127 [ Links ]

2. Sun GR, Saloojee H, Jansen van Rensburg M, Manning D. Stress during internship at three Johannesburg hospitals. S Afr Med J 2008;98(1):33-35. [ Links ]

3. Blitz J, Kok N, van Heerden B, van Schalkwyk S. PIQUE-ing an interest in curriculum renewal. Afr J Health Professions Educ 2014;6(1):23-27. https://doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.318 [ Links ]

4. Yiga S, Botes J, Joubert G, et al. Self-perceived readiness of medical interns in performing basic medical procedures at the Universitas Academic Health Complex in Bloemfontein. SA Fam Pract 2016;58(5):179-184. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786190.2016.1228560 [ Links ]

5. Jaschinski J, de Villiers MR. Factors influencing the development of practical skills of interns working in regional hospitals of the Western Cape Province of South Africa. SA Fam Pract 2008;50(1):70-70d. https://doi.org/10.1080/20786204.2008.10873676 [ Links ]

6. Nkabinde TC, Ross A, Reid S, Nkwanyana NM. Internship training adequately prepares South African medical graduates for community service - with exceptions. S Afr Med J 2013;103(12):930-934. [ Links ]

7. Burch V, van Heerden B. Are community service doctors equipped to address priority health needs in South Africa? S Afr Med J 2013;103(12):905. [ Links ]

8. Scicluna HA, Grimm MC, Jones PD, Pilotto LS, McNeil HP. Improving the transition from medical school to internship - evaluation of a preparation for internship course. BMC Med Educ 2014;14(1):23. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-23 [ Links ]

9. Prince K, van de Wiel M, van der Vleuten C, Boshuizen H, Scherpbier A. Junior doctors' opinions about the transition from medical school to clinical practice: A change of environment. Educ Health Chang Learn Pract 2004;17(3):323-331. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576280400002510 [ Links ]

10. Health Professions Council of South Africa. Core competencies for undergraduate students in clinical associate, dentistry and medical teaching and learning programmes in South Africa. 2014. http://www.hpcsa.co.za/uploads/editor/UserFiles/downloads/medical_dental/MDB CoreCompetencies-ENGLISH-FINAL2014.pdf (accessed 11 May 2017). [ Links ]

11. Van Heerden BB. Effectively addressing the health needs of South Africa's population: The role of health professions education in the 21st century. S Afr Med J 2012;103(1):21-22. [ Links ]

12. Bola S, Trollip E, Parkinson F. The state of South African internships: A national survey against HPCSA guidelines. S Afr Med J 2015;105(7):535-539. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJNEW.7923 [ Links ]

13. Van Niekerk J. Internship and community service require supervision. S Afr Med J 2012;102(8):638. [ Links ]

14. Meintjes Y. The 2-year internship training. S Afr Med J 2003;93(5):336-337. [ Links ]

15. Prinsloo A. A two-year internship programme for South Africa. SA Fam Pract 2005;47(5):3. [ Links ]

16. Van Schalkwyk S, Blitz J, Couper I, de Villiers M, Muller J. Breaking new ground: Lessons learnt from the development of Stellenbosch University's Rural Clinical School. In: Padarath A, Barron P, eds. South African Health Review 2017. Durban: Health Systems Trust, 2017. [ Links ]

17. Van Schalkwyk SC, Bezuidenhout J, de Villiers MR. Understanding rural clinical learning spaces: Being and becoming a doctor. Med Teach 2015;37(6):589-594. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.956064 [ Links ]

18. Braun V, Clarke V Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3(2):77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp0630a [ Links ]

19. Caballero CL, Walker A, Tyszkiewicz MF. The Work Readiness Scale (WRS): Developing a measure to assess work readiness in college graduates. J Teach Learn Grad Employ 2011;2(2):41-54. [ Links ]

20. Walker A, Yong M, Pang L, Fullarton C, Costa B, Dunning AMT. Work readiness of graduate health professionals. Nurse Educ Today 2013;33(2):116-122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2012.01.007 [ Links ]

21. Muthaura PN, Khamis T, Ahmed M, Hussain SR. Perceptions of the preparedness of medical graduates for internship responsibilities in district hospitals in Kenya: A qualitative study. BMC Med Educ 2015;15(1):178. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0463-6 [ Links ]

22. Eley DS. Postgraduates' perceptions of preparedness for work as a doctor and making future career decisions: Support for rural, non-traditional medical schools. Educ Health 2010;23(2):374. [ Links ]

23. Dudley NM, Orvis K, Lebiecki JE, Cortina JM. A meta-analytic investigation of conscientiousness in the prediction of job performance: Examining the intercorrelations and the incremental validity of narrow traits. J Appl Psychol 2006;91(1):40-57. https://doi.org/10.1037.0021-9010.91.1.40 [ Links ]

24. Costa P, Alves R, Neto I, Marvão P, Portela M, Costa MJ. Associations between medical student empathy and personality: A multi-institutional study. PLoS ONE 2014;9(3):1-7. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089254 [ Links ]

25. Cave J, Woolf K, Jones A, Dacre J. Easing the transition from student to doctor: How can medical schools help prepare their graduates for starting work? Med Teach 2009;31(5):403-408. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590802348127 [ Links ]

26. Wagner P, Hendrich J, Moseley G, Hudson V Defining medical professionalism: A qualitative study. Med Educ 2007;41(3):288-294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02695.x [ Links ]

27. Tallentire VR, Smith SE, Wylde K, Cameron HS. Are medical graduates ready to face the challenges of foundation training? Postgrad Med J 2011;87(1031):590-595. https://doi.org/10.1136/pgmj.2010.115659 [ Links ]

28. Sein NN, Tumbo J. Determinants of effective medical intern training at a training hospital in North West Province, South Africa. Afr J Health Professions Educ 2012;4(1):10-14. https://doi.org/10.7196/AJHPE.100 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

M de Villiers

mrdv@sun.ac.za

Accepted 12 April 2018