Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.108 no.8 supl.1 Pretoria Ago. 2018

FOREWORD

Professor Mike Kew and the Royal Free Hospital

M Pinzani

MD, PhD, FRCP; Sheila Sherlock Chair of Hematology, and Director, University College London Institute for Liver and Digestive Health, Division of Medicine, Royal Free Hospital, London, UK

The Royal Free Hospital in London is one of the world's foremost landmarks in hepatology, being the hospital where Professor Dame Sheila Sherlock worked, providing key contributions to the discipline. Sheila Sherlock's legacy is a most impressive establishment, with possibly hundreds of clinical and research fellows having received training and inspiration from her, and subsequently from her closest disciples after her death in 2002. Many of these young trainees came to London from different parts of the world, and went back to their countries fundamentally primed to become leading hepatologists.

The original Royal Free Hospital was located in the centre of London, in Gray's Inn Road, and was then moved to the new establishment in Hampstead, North London, in 1974.

Professor Mike Kew joined the group led by Sheila Sherlock in 1969, and spent 1 year as specialist registrar at the Royal Free in Gray's Inn Road. London was probably the most exciting city in the world at the time. Everything seemed to happen there, with new trends originating from what was defined as 'swinging London'. In the imagination of somebody from South Africa, London was still the capital of the great British Empire, when in reality, the empire was over, and London was pursuing a different and far brighter future.

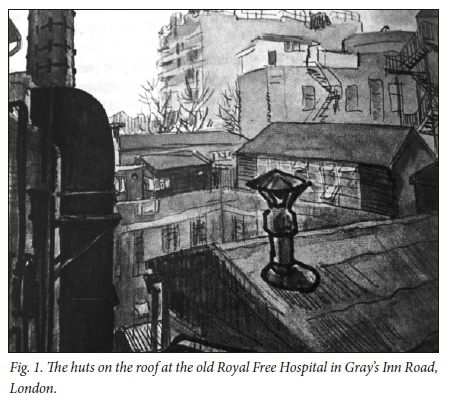

However, the old Royal Free in Gray's Inn Road was an outdated structure, totally insufficient to satisfy the blossoming rapid expansion of the more and more specialised branches of medicine. The building was like an old veteran of many battles, full of glory and medals, but close to ruin. Hepatology, one of the newcomers in the race to medical specialisation, was mostly relegated to an interconnected series of huts on the roof of the old hospital building (Fig. 1). I can imagine young Dr Kew, used to the warmth, spaces and colours of Africa, encountering the grey and humid London atmosphere, and moving from one hut to another between ward rounds and academic meetings.

In the memory of the few people I was able to contact and ask about the days of Mike Kew in London, and most notably one of my predecessors, Professor Neil MacIntyre, Mike was regarded as a shy but extremely knowledgeable doctor, and, apparently, a formidable tennis player. This may have contributed to his making a favourable impression on Dame Sheila, who loved tennis and did not allow anybody to beat her. In this regard, it would be interesting to know Mike's point of view!

The intense activity of Mike Kew at the Royal Free was largely concentrated on renal impairment in patients with cirrhosis of the liver. In 1971, Mike published his first landmark paper on this topic in The Lancet.1 By employing the innovative 133Xe washout technique, Mike and colleagues clearly demonstrated for the first time that a decrease in creatinine clearance is invariably associated with significant cortical hypoperfusion, likely attributable to active vasoconstriction of the cortical vessels. In a paper published in 1972,2 Mike and coworkers showed that an identical situation occurs in non-cirrhotic portal hypertension, and established the concept that vasoconstriction of the renal cortex occurs as a consequence of portal hypertension independently of the progressive failure of liver function typical of advanced cirrhosis. Working along these lines, these authors provided the first characterisation of portal hypertension in primary biliary cirrhosis.3 Another key intuition in this pioneering area of hepatology was the relationship between the circulatory derangement typical of decompensated cirrhosis and renal function.4 In this paper, the authors showed that the administration of octapressin, a vasopressin analogue, was able to improve renal function only in those patients in whom the drug increased a very low mean arterial pressure, thus establishing the relationship between effective blood volume and glomerular filtration rate in cirrhosis. Taken together, these acquisitions represent the very fundamental basis of our current understanding of renal function in cirrhosis, the hepatorenal syndrome and the relative therapeutic approaches. I vividly remember quoting Mike Kew's paper in my MD thesis, and I was deeply honoured to meet him for the first time in Cape Town.

This intense and innovative research activity had distracted Mike Kew from his original and everlasting love: hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Indeed, he published only one paper on this topic with Sheila Sherlock, dedicated to the diagnosis of this malignancy.5 I can imagine that Mike was probably the hepatologist with the greatest experience in HCC at the Royal Free, as a result of the far higher incidence of this cancer in Africa, and the still poor recognition of the association between chronic liver disease and HCC in Europe and the USA.

I feel honoured to celebrate in this article the association between the Royal Free Hospital and one of its most renowned fellows in hepatology. Mike's lifetime achievements are a great source of motivation for me and for the young research fellows that I am honoured to mentor and host, thus maintaining Sheila Sherlock's legacy.

References

1. Kew MC, Brunt PW, Varma RR, Hourigan KJ, Williams HS, Sherlock S. Renal and intrarenal blood-flow in cirrhosis of the liver. Lancet 19713(7723):504-510. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(71)90435-1 [ Links ]

2. Kew MC, Limbrick C, Varma RR, Sherlock S. Renal and intrarenal blood flow in non-cirrhotic portal hypertension. Gut 1972;13:763-767. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.13.10.763 [ Links ]

3. Kew MC, Varma RR, Dos Santos HA, Scheuer PJ, Sherlock S. Portal hypertension in primary biliary cirrhosis. Gut 1971;12:830-834. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.12.10.830 [ Links ]

4. Kew MC, Varma RR, Sampson DJ, Sherlock S.The effect of octapressin on renal and intrarenal blood flow in cirrhosis of the liver. Gut 1972;13:293-296. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.13.4.293 [ Links ]

5. Kew MC, Dos Santos HA, Sherlock S. Diagnosis of primary cancer of the liver. Br Med J 1971;4(5784):408-411. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.4.5784.408 [ Links ]