Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.108 no.3 Pretoria mar. 2018

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2018.v108i3.12683

RESEARCH

Restaurant smoking sections in South Africa and the perceived impact of the proposed smoke-free laws: Evidence from a nationally representative survey

M LittleI; C van WalbeekII

IMA (Economics); Economics of Tobacco Control Project, Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit, School of Economics, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIPhD (Economics); Economics of Tobacco Control Project, Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit, School of Economics, University of Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. The South African Minister of Health announced in 2016 that he intends to introduce tobacco control legislation that will prohibit smoking in restaurants. This will substantially strengthen the Tobacco Products Control Act (1993, as amended), which currently allows restaurants to have a dedicated, enclosed indoor smoking area.

OBJECTIVES. To analyse current smoking policies of restaurants, whether and how these policies have changed over the past decade, and restaurateurs' attitudes to the proposed legislative changes.

Methods. From a population of nearly 12 000 restaurants, derived from four websites, we sampled 2 000 restaurants, stratifying by province and type (independent v. chain) and disproportionately sampling small strata to ensure meaningful analysis. We successfully surveyed 741 restaurants, mostly by phone. We also surveyed 60 franchisors from a population of 82 franchisors.

RESULTS. Of the restaurants sampled, 44% were 100% smoke-free, 44% had smoking sections outside, 11% had smoking sections inside, and 1% allowed smoking anywhere. Smoking areas were more common in independent restaurants (62%) than franchised restaurants (43%). Of the restaurants with a smoking section, 33% reported that the smoking sections were busier than the non-smoking sections. Twenty-three percent of restaurants had made changes to their smoking policies in the past 10 years, mostly removing or reducing the size of the smoking sections. Customer requests (39%), compliance with the law (35%) and cost and revenue pressures (14%) were the main reasons for changing smoking policies. Of the restaurant respondents 91% supported the current legislation, while 63% supported the proposed legislative changes; 68% of respondents who were aware of the proposed legislation supported it, compared with 58% of respondents who were not aware of the proposed legislation.

CONCLUSIONS. In contrast to the vehement opposition to the 1999 legislation, which resulted in restaurants going partially smoke-free in 2001, there was limited opposition from restaurants to the proposed legislative changes that would make restaurants 100% smoke-free. Support for the proposed legislation will probably increase as the restaurant industry and the public are made more aware of the proposed legislative changes, although public opinion is vulnerable to tobacco industry-led campaigns.

As a party to the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which came into effect in April 2005, South Africa (SA) is obligated to prioritise the protection of public health by implementing effective tobacco control measures. In 2016, in line with the FCTC Article 8 guidelines, the SA Minister of Health proposed an amendment to the Tobacco Products Control Act (Act 83 of 1993) to make seating areas in restaurants 100% smoke-free, making designated smoking sections obsolete.[1] The proposed amendment to the existing tobacco control legislation aims to achieve what the Tobacco Products Control Amendment Act of 1999 failed to achieve, namely comprehensive restrictions on smoking in all hospitality establishments. Although some anti-tobacco advocates argued strongly for a comprehensive ban on smoking in hospitality establishments in the late 1990s, the National Department of Health, under pressure from the tobacco industry and the Federated Hospitality Association of South Africa (FEDHASA), agreed to dedicated smoking areas.[2] Based on a smoking prevalence of about 25% at the time, it was agreed that restaurants were able to set aside a maximum of 25% of their floor space for smoking areas. In 2003, the Republic of Ireland became the first country to implement comprehensive smoke-free legislation.

Two studies investigated the impact of the 1999 legislation (which became effective in July 2001). One study used survey data from over 1 000 restaurants,[3] and another analysed restaurant tax revenues (as a proxy for restaurant revenue) from before and after the enactment of the legislation.[4] These studies found that, in contrast to the dire predictions by the tobacco industry and FEDHASA, the legislation had minimal impact on restaurant revenues and patronage, although the impact was not entirely uniform across restaurant types. Franchised restaurants reported somewhat higher set-up costs to accommodate smokers, while independent restaurants, which were somewhat less accommodating to smoking clients, reported slightly lower revenues after the legislation was enacted.

Much has happened since restaurants became partially smoke-free in 2001. The prevalence of smoking has continued to decrease, as fewer people have initiated smoking and some smokers have quit.[5,6] Smoking has become increasingly socially unacceptable.

Objectives

The primary objective of this article is to inform policy-makers and other interested parties on the current smoking policies of restaurants, whether and how these policies have changed over the past decade, and restaurateurs' attitudes to the proposed legislative changes. We hope that, as well as providing an analysis of the past, it will inform the policy debate about smoke-free public places.

Methods

A total population of nearly 12 000 SA restaurants was obtained via four websites - the Yellow Pages, Zomato, Eat Out and Dining Out. The observations were stratified into 18 strata by province and type of restaurant (independent v. chains). For the purposes of this article, restaurant chains (mainly franchised restaurants) are defined as five or more restaurants under the same brand name. From the total population, 2 000 restaurants were selected using disproportionate sampling to ensure meaningful analysis of small strata.

Ethics approval was granted by the University of Cape Town's Commerce Faculty's Ethics in Research Committee (ref. no. 6166109). The survey was conducted in December 2016 by 15 surveyors. The survey was directed at restaurant owners and managers, and was mostly completed telephonically, with a small proportion of restaurants completing it online. Participation was incentivised by the chance to win a ZAR1 000 online voucher. Only restaurants with sit-down sections were included in the survey, since the proposed smoke-free legislation does not affect takeaway-only restaurants.

All data were weighted to account for the stratified survey design and non-response. A comparison of weighted and unweighted results yielded no major inconsistencies, and all results presented below are weighted. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported for each statistic (in parentheses), either in the tables or in the text. If the 95% CI is shown in the table, it is not repeated in the text.

Approximately a third of SA restaurants belong to a restaurant chain. Restaurant chains, most of which are franchised, have centralised decision-making processes. An additional survey was completed with franchise managers in January 2017 that aimed to document the current smoking policies, and perceptions of the proposed amendments, of large franchisors (i.e. the central body that controls the various franchised restaurants). A total of 82 franchisors were sampled.

Results

Survey responses

The response rate among restaurant respondents was 37%, with significantly higher response rates from franchised restaurants (43%) than independent restaurants (34%) (Table 1). Overall, 44% of restaurants were uncontactable (despite multiple attempts via phone and email) or the restaurateurs could not find a convenient time to answer the survey; 16% of restaurants refused to take part; and 3% of the restaurant phone numbers were not for sit-down restaurants. The franchisor survey had a response rate of 73%, with 60 of the 82 franchisors completing the survey (mainly telephonically, with a few online submissions). The main reason for non-response was that franchisors could not find a convenient time to take the survey (24%, or n=20 franchisors).

Restaurant respondents were mainly managers (69%, 95% CI 65.8 -72.7), or owners (27%, 95% CI 23.5 - 30.2), with a small proportion of waitrons (4%, 95% CI 2.7 - 5.7). Of the franchisor respondents, 62% (95% CI 48.0 - 73.9) were directors or executives and 38% (95% CI 26.0 - 52.0) lower-level managers or other staff.

The prevalence of smoking (personal smoking status) was significantly higher among the restaurant survey respondents (33%, 95% CI 29.7 - 36.9) than the franchisor management respondents (20%, 95% CI 11.7 - 32.9), and the average for SA adults (20%).[5]

About half (52%, 95% CI 48.0 - 55.5) of the restaurateurs sampled identified their establishments as casual dining establishments, while 18% (95% CI 15.0 - 20.7) identified themselves as fine-dining restaurants, 16% (95% CI 13.8 - 19.6) as coffee shops and 14% (95% CI 11.8 - 16.7) as fast-food places (or quick-service restaurants).

Distribution of restaurant smoking sections

At the time of the study, 44% (95% CI 40.6 - 48.0) of SA restaurants had chosen to be completely smoke-free, while 44% (95% CI 39.8 -47.1) had an outside smoking area, 11% (95% CI 9.0 - 13.7) had a designated inside smoking area (a few had both inside and outside areas), and 1% (95% CI 0.6 - 2.4) allowed smoking anywhere. Smoking areas were much more common in independent restaurants (62%) than franchised restaurants (43%) (Table 2).

There was a strong correlation between serving alcohol and having a smoking section - 62% of restaurants that served alcohol had designated smoking areas v. 37% of those that did not serve alcohol. Similarly, restaurants that stayed open late (which is correlated with serving alcohol) were much more likely to have a smoking section than those that closed earlier.

Smoking sections were markedly more common in large restaurants than in smaller ones. Two-thirds of restaurants (65%) with more than 100 seats had a smoking section, compared with 46% of restaurants with fewer than 100 seats. Restaurants located in hotels were more likely to have smoking sections than restaurants located in other areas. Restaurants in shopping malls were the least likely to have smoking sections, as they are obligated to follow the (often strict) shopping mall smoking regulations.

In contrast to the early 2000s, when the majority of smoking sections were busier than the non-smoking areas,[3] only 33% of respondents to the current survey indicated that the smoking areas were busier than the rest of the restaurant. Smoking section occupation rates did not vary substantially between independent and franchised restaurants, between large and small restaurants, or between restaurant locations. The relative occupation rates were correlated with the restaurant's closing time and whether it held a liquor licence. On average, 39% of restaurants that stayed open beyond 22h00 had smoking sections that were busier than the rest of the restaurant, relative to 35% of restaurants that closed between 18h00 and 22h00 and just 22% of restaurants that closed before 18h00. Only 16% of restaurants that did not serve alcohol had relatively busier smoking sections, compared with 37% of restaurants that served alcohol.

Changes in restaurant smoking policies in the past decade

In total, 23% of restaurants had changed their smoking policy in some way in the past 10 years. The majority of these restaurants had become completely smoke-free (35%, 95% CI 28.2 - 43.1), moved the smoking section outside (16%, 95% CI 11.0 - 22.7) or reduced its size (16%, 95% CI 11.2 - 21.7). Very few restaurants had introduced a smoking section where previously they had been smoke-free (4%, 95% CI 1.9 - 8.6), enlarged their smoking section (4%, 95% CI 1.7 - 8.5) or moved it inside (4%, 95% CI 1.8 - 8.5). While 17% (95% CI 12.3 - 24.2) of restaurants that had changed their smoking policies in the past 10 years indicated that they had previously allowed smoking everywhere and had since installed a smoking section, it is unclear whether these restaurants were late in complying with the 2001 legislation, or if the respondent recalled the date of the smoking policy change incorrectly. Overall, 6% (95% CI 3.5 - 11.2) of restaurateurs could not recall what change had been implemented. Some restaurants implemented multiple changes. As these results were self-reported, they depend on the knowledge and length of tenure of the respondent, which may introduce some recall bias.

Casual and fine-dining restaurants were the most likely to have implemented some smoking policy change (29% (95% CI 25.0 - 34.3) of these restaurants having done so), while only 7% (95% CI 3.2 -13.4) of fast-food places had chosen to do so. Restaurant size matters: 37% of restaurants with over 100 seats had a change in smoking policy, compared with just 11% of restaurants with less than 100 seats. In addition, restaurants that closed late in the evening and/or served alcohol were significantly more likely to have implemented a smoking section change than restaurants that closed earlier and/or did not serve alcohol, as indicated in Table 2.

The reasons for the restaurants' changes to their smoking policy were customer requests (39% of restaurants, 95% CI 31.9 - 47.2), and to remain in compliance with the law (35%, 95% CI 27.9 - 42.8). Other reasons included financial drivers such as pressures to lower maintenance costs and/or drive revenue growth by attracting more customers (14%, 95% CI 9.7 - 20.6), orders from their franchise management or changes in shopping mall policies (8%, 95% CI 4.6 -13.5), staff complaints (5%, 95% CI 2.8 - 10.3), the decision to combine changes with planned renovations (4%, 95% CI 2.1 - 8.4) or instructions from authorities (3%, 95% CI 1.5 - 7.8). A number of restaurants indicated more than one reason for the change in smoking policy. A small proportion of respondents (7%, 95% CI 3.9 - 11.7) could not recall the reason for the change in their smoking policy.

To understand the customer viewpoint, we asked restaurateurs to reflect on their customers' reactions to the smoking policy changes. For restaurants that had removed the smoking section completely, 41% (95% CI 28.6 - 53.9) of restaurateurs thought that on average their customers approved, 39% (95% CI 27.1 - 52.3) thought that their customers disapproved, 15% (95% CI 8.0 - 27.2) thought that their customers were indifferent to the change, and 5% (95% CI 1.6 - 15.0) were unsure. Where the restaurant had introduced a smoking section where previously one could smoke anywhere, reduced the size of the smoking section or moved the smoking section outside, a higher proportion of respondents thought that their customers approved (43%, 95% CI 33.1 - 53.9), while 24% (95% CI 16.0 - 34.0) thought that their customers were indifferent, 27% (95% CI 18.8 - 37.7) thought that their customers disapproved, and 6% (95% CI 2.3 - 13.1) were unsure of their customers' views.

Restaurant industry views on the proposed smoke-free laws

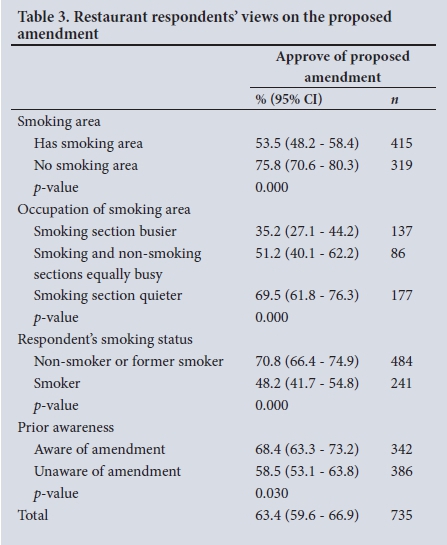

Restaurateurs overwhelmingly approved of the current smoking laws that allow separate smoking sections (91%, 95% CI 88.8 - 93.1), while only 8% (95% CI 6.2 - 10.3) disapproved and 1% (95% CI 0.3 - 1.8) were undecided (Table 3). Approval ratings were lower with regard to the proposed smoke-free amendment, but nevertheless the majority (63%, 95% CI 59.6 - 66.9) of restaurant respondents approved; 34% (95% CI 30.5 - 37.8) disapproved and 3% (95% CI 1.6 - 4.1) were undecided. At the time of the survey, it was not clear whether the smoking ban will include outside smoking areas. If smoking is banned in outside smoking areas, approval rates may decrease.

The level of support for the proposed amendment varied according to whether the respondent's restaurant had a smoking section, the respondent's personal smoking status, and any prior knowledge of the amendment. Of restaurateurs whose establishments had smoking sections, 53% supported the amendment, relative to 75% of those working in entirely non-smoking restaurants. Furthermore, restaurateurs whose smoking sections were busier than the nonsmoking sections were much more sceptical - only 35% of these restaurateurs approved of the proposed amendment, compared with 69% of restaurants with a less busy smoking section.

Although respondents were asked to give their professional opinion rather than their personal opinion, the smoking status of the respondent is significantly correlated with their attitude. Nearly three-quarters (71%) of non-smoking respondents approved of the proposed amendment, while only 48% of smoking respondents approved. On average, 50% (95% CI 46.4 - 54.0) of restaurateurs indicated some knowledge of the proposed amendment, prior to having it explained fully to them by the surveyor. This knowledge is correlated with supporting the proposed amendment - 68% of respondents with prior knowledge of the proposed amendment approved of it, while only 58% of those who were not aware of the amendment approved.

When asked how they would respond to the proposed amendment, 75% (95% CI 69.7 - 80.4) of restaurateurs whose establishments had smoking sections indicated that they would take action only if and when the proposed amendment is written into law. Assuming that the legislation will be passed, 55% (95% CI 48.3 - 62.0) hoped to continue to allow smoking in outside smoking areas if permitted under the proposed laws, 18% (95% CI 13.1 - 23.4) intended removing their smoking sections (knocking down walls and removing ventilation where necessary), a small minority expressed concern that they would need to shut down or reduce their operations (6%, 95% CI 3.4 - 10.1), and 21% (95% CI 16.0 - 27.5) were uncertain what action they would take.

Discussion

The Tobacco Products Control Amendment Act of 1999 aimed to protect non-smokers from environmental tobacco smoke by making restaurants smoke-free. Under pressure from the tobacco industry and FEDHASA, restaurants were allowed (but not obliged) to set apart a maximum of 25% of floor space for smoking patrons. The debate that preceded the passing of this legislation was heated, with predictions of significant losses to restaurants being made by the tobacco industry and FEDHASA.[2] Opinions have mellowed substantially over the past two decades. We found near-universal support for the current smoking laws among restaurant owners and managers.

In the past 10 years many restaurants have voluntarily become smoke-free, in part to avoid the costs of setting up separate smoking sections and also owing to falling demand from customers. Given the international legislative trend towards smoke-free restaurants (45 countries have adopted a completely smoke-free law since 2007[7]), many restaurateurs have also been pre-empting such legislation in SA. In our survey, these restaurants report no significant reduction in either patronage or profits as a result of becoming smoke-free. These findings are in line with other studies in countries that have instituted 100% smoking bans.[8]

In this context, the Minister of Health has proposed an amendment to the smoking laws, to remove the dedicated indoor smoking sections and enforce 100% smoke-free hospitality establishments. The proposed amendment would improve the health of hospitality-sector staff and that of the general public, both by reducing exposure to second-hand smoke and by discouraging smoking patrons from smoking, thereby further 'denormalising' smoking.

Our survey indicates that nearly two-thirds of restaurant owners and managers support the proposed smoke-free amendment. FEDHASA has been silent on the matter so far, in stark contrast to the late 1990s. One of the authors of this article was involved in a socioeconomic impact assessment to investigate the impact of making all hospitality establishments smoke-free. FEDHASA and the tobacco industry were invited to give their views, and while the tobacco industry provided much input, no response from FEDHASA was received.

Study limitations

This article is subject to a number of limitations. Given that the restaurant population (from which the restaurant sample is drawn) was derived from online websites, it is likely to under-represent smaller, less upmarket and rural restaurants. The relatively low response rate suggests that a degree of caution should be exercised when generalising the results. In addition, the data will fail to capture information on restaurants that have closed down (potentially as a result of changes to smoking laws), leaving the results vulnerable to endogeneity. Furthermore, all inference relies on the inherently subjective responses of restaurateurs, leaving the analysis vulnerable to recall bias and speculation. If and when the amendment is enacted, additional research comparing objective data from before and after the imposition of the legislation will add valuable insight into the economic impact of the smoke-free laws.

Conclusions

The proposed legislation that aims to make all restaurants 100% smoke-free will make smoking sections in restaurants obsolete. This study has shown that, over the past decade, there has been a trend to reduce the smoking sections in restaurants, move the smoking sections outside, or go completely smoke-free. The proposed legislation will substantially speed up a process that has already begun.

The legislation currently in place (i.e. smoke-free establishments with dedicated smoking areas) was vehemently opposed when it was debated in the late 1990s. The tobacco industry and the hospitality federation argued that the restaurant industry would be seriously hurt by restrictions on smoking. This rhetoric proved false. The current legislation had overwhelming support among the restaurateurs interviewed, proving that mindsets can change and that most people want to dine out in establishments that are not filled with harmful tobacco smoke.

Nearly two-thirds of the respondents supported the proposed legislation to make restaurants 100% smoke-free, but this support could waver in the face of a tobacco industry-led information campaign. The experience of the 1999 legislation strongly suggests that the support for legislation increases after it has been implemented. Respondents who had been aware of the proposed legislation were more supportive of it than those who were not. The message of this research is that government and media should inform the public of the proposed legislation and that government should not delay the implementation of this amendment.

Acknowledgements. We thank all the respondents for participating in this survey, the surveyors for their hard work, and Caitlin Allan for her assistance in the data analysis.

Author contributions. CvW conceptualised the research. ML and CvW designed the questionnaires. ML managed the survey and analysed the data. The results were synthesised into a long report (available on request), and this subsequent short article was written by both authors.

Funding. This research was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation through the African Capacity Building Foundation (IRMA 20177).

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Moodley V. Tobacco Control Legislation in South Africa, Commemoration of World Environmental Health Day - 27 Sept 2016. In National Department of Health; 2016. p. 1-20. http://slideplayer.com/slide/11644885/ (accessed 15 January 2018). [ Links ]

2. Van Walbeek C. Arguments For and Against Advertising Bans and Clean Indoor Air Policies: The South African Experience. Cape Town: University of Cape Town, Economics of Tobacco Control Project, Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit, 2001. [ Links ]

3. Van Walbeek C, Blecher E, van Graan M. Effects of the Tobacco Products Control Amendment Act of 1999 on restaurant revenues in South Africa - a survey approach. S Afr Med J 2007;97(3):208-211. [ Links ]

4. Blecher E. The effects of the Tobacco Products Control Amendment Act of 1999 on restaurant revenues in South Africa: A panel data approach. S Afr J Econ 2006;74(1):123-130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1813-6982.2006.00052.x [ Links ]

5. Vellios N, van Walbeek C. Determinants of regular smoking onset in South Africa using duration analysis. BMJ Open 2016;6:1-9. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011076corr1 [ Links ]

6. Chelwa G, van Walbeek C, Blecher E. Evaluating South Africa's tobacco control initiative: A synthetic control approach. Economic Research Southern Africa. December 2015. http://www.econrsa.org/node/1159 (accessed 27 December 2017). [ Links ]

7. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic 2017: Monitoring tobacco use and prevention policies. http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2017/en/ (accessed 27 December 2017). [ Links ]

8. Scollo M, Lal A. Summary of studies assessing the economic impact of smoke-free policies in the hospitality industry. 2008. 13 February 2008, revised 21 February 2008. http://www.academia.edu/6051751/Summary_of_Studies_Assessing_the_Economic_ Impact_of_Smoke-Free_Policies_in_the_Hospitality_Industry (accessed 15 January 2018). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

M Little

megan.little1@gmail.com

Accepted 24 August 2017.