Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.107 n.11 Pretoria Nov. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2017.v107i11.12379

RESEARCH

Access to and utilisation of healthcare services by sex workers at truck-stop clinics in South Africa: A case study

S C FobosiI; S T Lalla-EdwardI; S NcubeII; F ButheleziII; P MatthewIII; A KadyakapitaIV; M SlabbertV; C A HankinsVI, VII; W D F VenterVIII; G B GomezIX, X

IMA; Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIWits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIINorth Star Alliance, Durban, South Africa

IVMD; North Star Alliance, Durban, South Africa

VMBA; Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

VIMD, PhD; Department of Global Health and Amsterdam Institute for Global Health and Development, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands

VIIMD, PhD;Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics, and Occupational Health, Faculty of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, Canada

VIIIMD; Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IXPhD; Department of Global Health and Development, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK

XPhD; Department of Global Health and Amsterdam Institute for Global Health and Development, Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Sex worker-specific health services aim to respond to the challenges that this key population faces in accessing healthcare. These services aim to integrate primary healthcare (PHC) interventions, yet most services tend to focus on prevention of HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs). North Star Alliance (North Star) is a public-private partnership providing a healthcare service package in roadside wellness clinics (RWCs) to at-risk populations along transport corridors in sub-Saharan Africa.

OBJECTIVES. To inform future service development for sex workers and describe North Star's contribution to healthcare provision to this population in South Africa, we describe services provided to and utilised by sex workers, and their views of these services.

METHODS. Using a mixed-methods approach, we present quantitative analyses of anonymised North Star routine data for sex workers for October 2013 - September 2015, covering nine sites in seven provinces. Clinic visits were disaggregated by type of service accessed. We performed thematic analysis of 25 semi-structured interviews conducted at five clinics.

RESULTS. A total of 2 794 sex workers accessed RWCs during the 2 years. Sex workers attending clinics were almost exclusively female (98.2%) and aged <40 years (83.8%). The majority were South African (83.8%), except at Musina, where the majority of clients were Zimbabwean. On average, sex workers visited the clinics 1.5 times per person. However, in most cases only one service was accessed per visit. PHC services other than for HIV and STIs were accessed more commonly than HIV-specific services and STI treatment. There was an increase in the number of services accessed over time, the figure almost doubling from 1 489 during the first year to 2 936 during the second year. Although during recruitment participants reported having had sex in exchange for goods or money during the past 3 months, not all participants self-identified as sex workers during interviews; however, all reported feeling at higher risk of poor health than the general population owing to their involvement in sex work. Participants reported satisfaction with site accessibility, location and operating hours. Sex workers accessing sites described services as being suitable and accessible, with friendly staff.

CONCLUSIONS. RWCs were highly appreciated by the users, as they are suitable and accessible. The sex workers who used the clinics visited them irregularly, mostly for PHC services other than HIV and STIs. Services other than the one for which the sex worker came to the clinic rarely appeared to be offered. We recommend areas for service expansion.

Sex workers face a higher HIV burden and have less access to healthcare than the general population.[1] In South Africa (SA), the prevalence of HIV among sex workers has been reported to be very high in urban areas,[2] with overall odds of infection being up to five times higher among female sex workers than women in the general population.[3] Recently, the SA National Department of Health recognised this vulnerability and published the South African National Sex Worker HIV Plan (NSWP).[4] This plan aims to reach 70 000 sex workers over the next five 5 years with a comprehensive package of care, and to ensure that at least 95% of sex workers use condoms with their clients and partners, that gender-based violence falls by 50%, and that the global targets of 90-90-90 are met for sex workers (i.e. 90% of sex workers know their HIV status, 90% of those testing positive are on antiretroviral treatment (ART), and 90% of sex workers on ART are virally suppressed). However, these targets may be difficult to attain if sex worker programmes have limited coverage and are poorly co-ordinated.[5-7]

While access to healthcare for sex workers is critically important, healthcare services for this population are currently fragmented, with most sex worker projects focused on prevention of HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs).[5] In addition, there is an opportunity to expand the scope of HIV services provided by these projects. For example, while HIV testing and counselling (HCT) is common in most clinics offering services prioritised for sex workers, only a few service providers offer, on site, the full range of services prescribed by the NSWP, including CD4+ count testing, co-trimoxazole prophylaxis and ART. To increase the scope of HIV services available to sex workers at sex worker-dedicated sites, the SA government is piloting pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and immediate treatment (called UTT: universal test and treat) at dedicated sex worker sites that are already offering ART to sex workers.[8]

North Star Alliance (North Star) is a public-private partnership aiming to provide healthcare to at-risk populations along transport corridors in sub-Saharan Africa.[9] These populations include truck drivers, sex workers and their clients, and individuals from the surrounding communities that do not otherwise have access to clinics - therefore aiming to contribute to the improvement of service provision for sex workers nationally.

Objectives

To assess the extent of the use of North Star services by sex workers and satisfaction with the services, as well as to inform future service development for sex workers, we describe services provided by North Star in SA, their utilisation by sex workers, and sex workers' views on these services.

Methods

We used a mixed-method approach for this research. Quantitative and qualitative data were collected concurrently and analysed separately.

Setting

The study took place in nine sites in seven provinces of SA (Cato Ridge and Pongola (KwaZulu-Natal), Bloemfontein (Free State), Bloemhof (North West), Ngodwana (Mpumalanga), Musina (Limpopo), Upington (Northern Cape), and Pomona and City Deep (Gauteng). All clinics operate on weekdays and are typically open for a minimum of 6 hours. Operating hours for some clinics changed during the period after this research. However, at the time of data collection, Cato Ridge and Bloemhof were operating from 14h00 to 22h00, Upington from 18h00 to 22h00, Ngodwana from 11h00 to 19h00 and Musina from 07h00 to 15h00.

Clinics became operational at various times during the October 2013 - September 2015 review period. Cato Ridge, City Deep and Ngodwana all opened in September 2013, while Musina, Upington and Bloemhof opened in January 2014, February 2014 and March 2014, respectively. Pongola opened in June 2014, while City Deep closed in September 2014 and Bloemfontein opened. Pomona (replacement for City Deep) opened in January 2015.

North Star clinics offer not only HIV/STI-specific services such as condom distribution, STI syndromic treatment, HCT and tuberculosis (TB) screening, but also other PHC services such as malaria screening and treatment, and in some instances cervical cancer screening, family planning, and diagnosis and treatment of common illnesses. During the past 4 years, North Star expanded its services to include initiation and provision of ART. It was recently announced that six North Star sites had been included as part of the national pilot programme to expand services further to provide UTT and PrEP. This ART information is being reported elsewhere and is not included in the HIV visit information reported in this article.

Quantitative approach

Anonymised routinely collected data were extracted in April 2016 from the Corridor Medical Transfer System (COMETS), the clinical information management system used by North Star across all its sites. The COMETS database has predefined occupation categories that are completed by the healthcare worker during the initial client visit. We extracted information for the 2-year period 1 October 2013 - 30 September 2015. Information was obtained at three levels: (i) individual-level characteristics of patients attending the sites (sex, age, marital status, occupation and country of origin); (ii) visit-level characteristics describing site and date of visit; and (iii) service-level information describing the type of service accessed during each visit (i.e. PHC, HIV, TB, STI, malaria). COMETS has separate fields for recording HIV services, STI syndromic treatment, TB screening and referral, malaria (symptomatic treatment) and PHC services (listed under 'Setting'). Based on this, data were analysed and presented according to these categories. Since data were anonymised, visit-level information was paired to the sex worker using their COMETS identifier and date of birth. No names or country identity numbers were used or accessible.

The data recorded in COMETS were audited periodically as part of routine programmatic quality assurance. During these audits, the completeness, accuracy and correct transcribing of records were validated. All data were analysed using Stata version 12 (StataCorp, USA). Data on community members and truck drivers (published elsewhere) were excluded from this analysis.

Qualitative approach

Using a semi-structured interview guide, data were collected on access and utilisation at five SA sites in five provinces (Cato Ridge (KwaZulu-Natal), Bloemhof (North West), Ngodwana (Mpuma-langa), Musina (Limpopo) and Upington (Northern Cape)). These sites were chosen because they were operational at the start of the research project and were approved for participation by the local ethics committee. We aimed to achieve 30 interviews, six per site. Participant recruitment was completed in two ways. Clients who came to the clinic were informed of the study on their exit and asked if they wanted to participate. For the sex workers who knew about the clinics but did not access them, the catchment areas around the clinics were visited by interviewers (one male and one female) to recruit sex workers. Eligibility criteria included age >18 years, either having accessed the clinic or knowing about the clinic and not accessing it, and reporting having had sex in exchange for goods or money during the past 3 months.

Interviews were conducted in accordance with what made the participant feel comfortable or was consented to: location (in the clinic consulting room or in the vicinity of the clinic), interviewer (male or female), recording (audio-recorded or note taking only) and language (English or vernacular).

Audio recordings were transcribed and quality checked. In the case of translation, transcripts were back-translated. All non-recorded interviews were typed up as transcripts and quality checked against the notes. All interview data were imported and analysed using NVivo 10 (QSR International). Interview data were analysed into themes (thematic analysis): (i) nature and risks of sex work; (ii) service access and utilisation; and (iii) patient satisfaction. Distinctive remarks from the interviews are given as quotations.

Ethics considerations

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (ref. no. M140506) on 30 May 2014. In addition, North Star Alliance and the Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute (Wits RHI) signed a data user's agreement on 5 May 2014 to ensure that data were appropriately handled throughout the data management cycle. No personal identifiers were extracted for the quantitative data analysis and no names were recorded during the interviews. All participants provided consent for interviews. These consents were stored separately from the voice recordings and transcripts. All voice recordings and transcripts were labelled numerically and could not be linked to clients through the consent forms. All electronically stored data were password protected and available to selected researchers on the project. All paper-based project information was stored in a secure data-filing room compliant with Wits RHI, the ethical review board and good clinical practice standards.

Results

Quantitative results

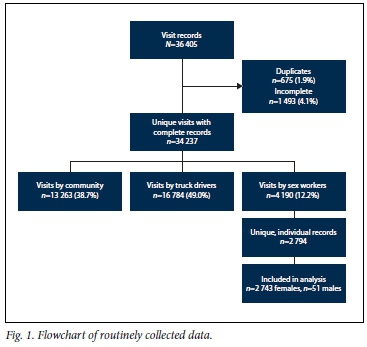

We extracted a total of 36 405 visit records for the 2-year study period at the nine sites (an average of >2 000 visits per site-year). We then excluded duplicates (n=675, 1.8%) and incomplete records (n=1 493, 4.1%) to finalise a database of 34 237 unique visits with complete records. Of these, 13 263 (38.7%) were visits by community members and 16 784 (49.0%) visits by truck drivers. In this analysis, we included 4 190 (12.2%) recorded visits by 2 794 sex workers, representing on average less than one visit per site-year by sex workers (Fig. 1).

The majority of sex workers attending North Star services were female (n=2 743, 98.2%), 83.8% were aged <40 years (n=2 342), and a minority (n=301, 10.8%) were married or in a stable relationship. The majority of sex workers were of SA origin (n=2 341, 83.8%), followed by those from Zimbabwe (n=388, 13.9%). Few sex workers from other countries (e.g. Angola, Malawi, Namibia, Senegal, South Sudan, Swaziland, Zambia) were recorded. Just under half (n=1 227, 43.9%) of all sex workers used the Upington clinic. Sex workers visited sites on average 1.5 times over the 2 years, accessing only one service at each visit for the majority of the visits (Table 1).

The demographic distribution of clinic attendees was similar across the sites, with the exception of sex workers presenting for care at Bloemhof and Musina. Women at Bloemhof were younger (18.0% <20 years old) than those at other sites, while women at Musina were mainly Zimbabweans (n=293, 81.8%), as opposed to other sites where South Africans formed the majority.

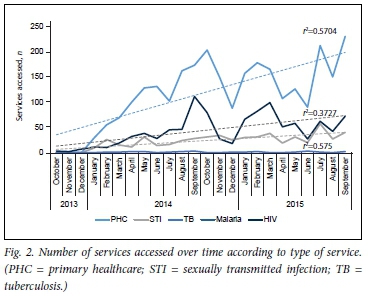

We observed an increase in the total number of services accessed over time, in particular for PHC services (r2=0.5704) (Fig. 2). PHC services were the type most accessed across all sites, followed by HIV-related services and then those for STIs. There were minimal visits for either TB or malaria compared with PHC or HIV.

Qualitative results

We completed 25 (24 users and 1 non-user) interviews out of a target of 30 planned. All participants were female, and the majority (n=16, 64.0%) were South African. The mean age was 28.6 years. Only two women had a stable partner (married or cohabiting), and the average number of dependants across all women was 2.6. All the participants except one from Bloemhof clinic had completed primary-level education or higher, and the majority (n=21, 84.0%) reported their monthly income as <ZAR5 000.

Nature and risks of sex work

Most participants reported being self-employed and earning an income in addition to sex work. Some women reported sex work as their first job, citing lack of employment opportunities in the formal sector as the reason. Some participants did not identify with the label of sex worker; this group reported mainly part-time sex work. In general, working hours varied, with most women selling services in the evening.

' I started [being a sex worker] a long time ago. I think I was 13. I work anytime ... I work anytime, you find that a truck driver comes here and says I am looking for a person, every time there is a truck that arrives here. He will go up and find a person anytime.' (Ngodwana participant)

'I am a sex worker, but I am also a co-ordinator for some red umbrella programme at GRIP [Greater Nelspruit Rape Intervention Project], I am a paralegal, SA human rights advisor under the programme of SW's [probably referring to SWEAT, Sex Worker Education and Advocacy Taskforce] home of sex workers.' (Ngodwana participant)

Participants cited a number of risks related to their occupation. These included clients refusing to pay after having had sex, abandoning them in unsafe areas, and refusing to use condoms. Some participants reported being attacked while asking for payment after rendering their services. There were also reports of regular condom failures.

'You can be beaten up whilst asking for money, some are rough, you meet rough riders like the condom can burst, some do it in a way that the condom can burst so you have to be very careful, some won't give you money, some are ... It's very dangerous.' (Musina participant)

Service access and utilisation

Most sex workers accessed condoms, pregnancy and HIV tests, and STI syndromic management at North Star clinics. For primary healthcare, they attended mainly to treat a cold or flu and to have check-ups, including non-communicable disease services. Some participants expressed a need for post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV.

'Ahhhh ... it once happened that the condom burst and I came and asked the sister to help me, she said I should wait and see what happens because she doesn't know what to give me. The second time I came was to check my blood pressure and then I came back again to check my blood pressure again [voice of the interviewer: high blood] yah I can say I came about four times.' (Ngodwana participant)

'Just because of, sometimes I want to know if I'm in good health.

[I] Also [go] to collect condoms; and when someone did not use a condom. (Bloemhof participant)

'It's like; maybe I am not feeling well or, feel like my urine is hot, something like that, and then go to the clinic and get help.' (Cato Ridge participant)

While for most of the participants being a sex worker did not influence their decision to seek healthcare, they understood the risks involved in the work and how this might affect their healthcare-seeking behaviour.

'No, it does not influence my decision of coming to the clinic. But, I do acknowledge that as a sex worker, I am very afraid of diseases such as STIs and AIDS. If I was not a sex worker, I would not come to the clinic as often. A lot of this is as a result of the lifestyle of sex workers which is money concentrated and being offered a lot of money not to use protection.' (Cato Ridge participant)

Sex worker satisfaction with services

The sex workers interviewed generally reported satisfaction with the location of the clinic, services offered, the operating hours, and the services being free of charge. When asked for suggestions to increase sex worker access to the clinic, most of the participants cited a revision of the clinic opening hours. While some women found the hours suitable, others requested opening times to be extended to Saturdays and weekdays until 22h00/midnight, or a 24-hour service (especially for emergencies). They commended the healthcare workers'/staff's good reception of them and noted that the staff treated them well. Most women reported satisfaction with the size of the clinic. Some of the participants tended to be shy about going to a public clinic/hospital, so the location of the RWC made it easy for them to use.

'I don't know, but it's right, it treats us well. So, I wouldn't say you should do this or remove it. I think it's right where it is, because there are some people who are shy of going to the clinic - so, I think it's good. It's right for people to go and test.' (Bloemhof respondent)

The majority of Cato Ridge participants noted that this particular clinic was not accessible to sex workers because of access restrictions at this truck stop. However, some of them mentioned that the clinic was within walking distance, which was convenient. At other sites (e.g. Musina, Ngodwana and Upington), the distance from workplace or home was considered suitable. In particular, at the Musina border centre, participants were satisfied with the location as they could access the clinic easily on the SA side.

'Yah, it's in the right place because we get helped a lot especially if you suffer from STIs, it helps a lot. I have known for a while now that this clinic is for sex workers. The sex workers get help a lot from the clinic. Even though some are not sex workers they do get helped a lot. I think it's right [voice of the interviewer: it's right]; just because it's in the rural areas it doesn't mean that it's not acceptable. It's far from Boven and even me I come here to test.' (Ngodwana participant)

Some of the dissatisfactions with the clinic services among the users were related to the lack of certain specific services. Most sex workers felt that the clinics should provide all healthcare services needed; for example, in addition to HIV testing, screening for diabetes should be available.

Discussion

The distribution of visits across sites was heterogeneous, with two sites (Ngodwana and Upington) providing most services to sex workers. The heterogeneity in utilisation can be attributed to the clinics being established at different times during the reported period, the size of the community around the clinic (i.e. number of sex workers available to access the clinic), the number of truck drivers accessing/present at the truck stop (potential clients for the sex workers), and security/police threats around the clinic (fear of being arrested or not being allowed into the truck stop where the clinic is located by the truck-stop security personnel).

Utilisation of healthcare services by sex workers was low (on average 1.5 visits per sex worker for the reported period). Our clinic attendees constitute a population that is mainly accessing PHC services other than for HIV and STI syndromic treatment. They mostly reported seeking curative care for a range of illnesses. These non-HIV, STI and TB visits do present the opportunity for the clinics' healthcare workers to offer the additional HIV, TB and STI services. The clinics' utilisation data reflect that while sex workers do access services, the services accessed are not linked to their high-risk profile. This could be attributed to their low-risk/no-risk self-perception, or their indeed not being at risk. Owing to the lack of limited access to services in their geographical locations, it is possible that female sex workers need to access other services in the same way that the general population does. This study could therefore be showing that female sex workers have similar (not restricted to sexual health only) health needs as the community, and North Star is assisting in addressing that gap.

Access together with the perception of the RWCs as suitable, appropriate and accessible, with friendly and approachable staff, provides an excellent opportunity to reach out and retain in care local sex worker communities. Since our study set out to explore access and describe utilisation, we cannot list definite reasons for low utilisation and infrequent visits. The proportion of sex workers in local communities is unknown, and it will be beneficial to conduct site-specific mapping and enumeration, mobility pattern analyses and/or behavioural surveillances combined with studies investigating reasons for low utilisation. This will assist North Star in planning for demand creation and improved linkage to and retention in care.

Our findings show that North Star is currently providing services that are helping to tackle two structural barriers previously reported globally by sex workers in access to care: (i) negative experiences with staff, including discriminatory attitudes from staff; open hostility and reluctance to treat them; and (ii) fragmentation of healthcare services available to sex workers.[10] There is also a need to increase demand through outreach and information campaigns, building on perceived accessibility of sites and appreciation of staff attitudes.

Another recommendation is to build on North Star's healthcare service delivery model to offer sex worker attendees provider-initiated and complementary health services when they access services (e.g. TB and STI screening for those accessing HIV testing). While sex worker-specific services represent a tailored solution for healthcare delivery, our results suggest that an all-inclusive approach to healthcare service delivery with empathetic staff is perceived as 'accessible' and is suitable to retain this population group in care. Additionally, it is important to recognise that the clinics do not offer some essential sexual and reproductive health (SRH) services for the prevention and care of adverse SRH outcomes to which female sex workers are particularly vulnerable, including unwanted pregnancies (currently there is a limited offering of contraception and no termination of pregnancy services) and sexual and other types of violence. Revision of the healthcare service package to incorporate these areas of care will increase the appropriateness of the services available to female sex workers. Lastly, if service utilisation still remains after improved access and acceptable and appropriate service delivery, North Star may need to consider conducting cost-benefit analyses of the smaller, less utilised clinics.

Study limitations

Our study has some limitations. Initially we aimed to interview both users and non-users of North Star services. However, out of all the sites where data collection was conducted, only one interview could be conducted with a non-user. This is because sex workers were difficult to identify (sometimes hiding their trade to avoid abuse or repercussions). To access them and invite them to participate, we required the assistance of North Star's staff, which limited our sampling frame to those known to the staff. Moreover, as with any analysis of routine data, we are dependent on the quality of the routine reporting. Significant efforts were made to achieve a suitable level of recording, with several rounds of audits and validation checks. We noted that there were missed opportunities for integration of services/provider-initiated services, and we acknowledge that the analysed dataset may have been too small to draw many conclusions from it, and that sex workers may not have required services in addition to what they requested, and/or that additional services may have been provided without being recorded. The main classification of clinic attendees into occupational groups depended largely on suitable and complete reporting from patients. With some sex workers not identifying themselves as such, we may have underestimated the total volume of visits and services accessed by this group. The demographics of the quantitative and qualitative samples did not match (i.e. there was a lower percentage of South Africans in the qualitative sample), but this was not too much lower than the quantitative sample. Lastly, although provincial-level sex worker population estimates are available, they cannot be used as an indication of the sex worker population in the catchment area of the truck-stop clinics.

Conclusion

RWCs were highly appreciated by the users, who reported them as being appropriate and accessible. Female sex workers visited the clinics irregularly, and when they did, they primarily accessed the clinic for PHC services other than HIV and STIs. Services other than the one for which the sex worker presented for were rarely offered. We therefore make several recommendations that can be further explored for service expansion in North Star.

Acknowledgements. The authors are most grateful to our participants for their time. We are also grateful to North Star Alliance's staff in the regional office (Durban) and in the participating sites for their dedication and assisting with the data collection and extraction. Finally, we would like to acknowledge Edwin Mkwanazi for his help during extraction of data.

Author contributions. STL-E, WDFV and GBG designed the study; FB and SCF conducted interviews; SN extracted COMETS data; SCF, STL-E, SN, FB, PM, AK, MS, CAH, WDFV and GBG analysed the data and interpreted the results; SCF, STL-E and GBG wrote the initial draft; and all authors critically reviewed and approved the final draft.

Funding. This work has been funded by a research and implementation grant from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Dutch Embassy for Southern African Region, Maputo, Mozambique, to North Star Alliance. The Amsterdam Institute for Global Health and Development (AIGHD) and Wits RHI hold separate subcontracts with North Star Alliance (AIGHD grant no. 0068 North Star - NSCDP; RHI grant no. D1404070). The study is supported by USAID-PEPFAR through a grant held by Wits RHI. North Star Alliance provided support in the form of a salary for co-authors PM and AK. The specific role of these authors is articulated in the 'author contributions' section.

STL-E was also funded by an African Doctoral Dissertation Research Fellowship award offered by the African Population and Health Research Center in partnership with the International Development Research Center and a Fellowship award provided by the Consortium for Advanced Research Training in Africa (CARTA). CARTA has been funded by the Wellcome Trust (UK) grant no. 087547/Z/08/Z), the Department for International Development under the Development Partnerships in Higher Education, the Carnegie Corporation of New York (grant no. B 8606), the Ford Foundation (grant no. 1100-0399), Google.org (grant no. 191994), Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (grant no. 54100029), and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (grant no. 51228).

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of any of the funders or the South African, Dutch or US governments.

Conflicts of interest. PM and AK are both employed by North Star Alliance. PM is currently regional director, southern Africa, and AK is a medical quality control officer. All the other authors have declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Beyrer C, Crago A-L, Bekker L-G, et al. An action agenda for HIV and sex workers. Lancet 2015;385(9964):287-301. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60933-8 [ Links ]

2. University of California, Anova Health Institute, Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Institute. South African Health Monitoring Survey (SAHMS): An Integrated Biological and Behavioural Survey among Female Sex Workers (2013-2014). San Francisco: UCSF, 2016. [ Links ]

3. Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12(7):538-549. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70066-X [ Links ]

4. South African National AIDS Council. The South African National Sex Worker HIV Plan, 2016 - 2019. Pretoria: SANAC, 2016. http://southafrica.unfpa.org/publications/south-african-national-sex-worker-hiv-plan-2016-2019 (accessed 30 January 2017). [ Links ]

5. Dhana A, Luchters S, Moore L, et al. Systematic review of facility-based sexual and reproductive health services for female sex workers in Africa. Glob Health 2014;10:46. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-8603-10-46 [ Links ]

6. Lafort Y, Greener R, Roy A, et al. Where do female sex workers seek HIV and reproductive health care and what motivates these choices? A survey in 4 cities in India, Kenya, Mozambique and South Africa. PloS One 2016;11(8):e0160730. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0160730 [ Links ]

7. Richter M. Sex work, reform initiatives and HIV/AIDS in inner-city Johannesburg. Afr J AIDS Res 2008;7(3):323-333. https://doi.org/10.2989/AJAR.2008.7.3.9.656 [ Links ]

8. National Department of Health, South Africa. National Policy on HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and Test and Treat (T&T). 2016. http://www.sahivsoc.org/Files/PREP%20and%20TT%20Policy%20-%20Final%20Draft%20-%205%20May%202016%20(HIV%20news).pdf (accessed 29 January 2017). [ Links ]

9. North Star Alliance. http://www.northstar-alliance.org/ (accessed 29 January 2017). [ Links ]

10. Global Network of Sex Workers Projects. Global Briefing Paper: Sex workers' access to HIV treatment around the world. Edinburgh, 2014. http://www.nswp.org/sites/nswp.org/files/Global%20Briefing%20-%20Access%20to%20HIV%20Treatment%20-%20English.pdf (accessed 9 October 2017). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

S T Lalla-Edward

slalla-edward@wrhi.ac.za

Accepted 30 May 2017