Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.107 n.7 Pretoria Jul. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2017.v107i7.12487

IN PRACTICE

ISSUES IN MEDICINE

Perceptions of nurses' roles in end-of-life care and organ donation - imposition or obligation?

K CrymbleI; J FabianII, III; H EtheredgeIV; P GaylardV

IDip Nursing. Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIMD. Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIIMD. Division of Nephrology, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IVMScMed, PhD Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre, Johannesburg, South Africa

VPhD. Data Monitoring and Statistical Analysis (DMSA), Johannesburg, South Africa

ABSTRACT

South Africa has a rich organ-transplant history, and studies suggest that the SA public supports organ donation. In spite of this, persistently low donor numbers are a significant challenge. This may be due to a lack of contextually appropriate awareness and education, or to barriers to referring patients and families in clinical settings. It may also be due to ad hoc regulations that are not uniformly endorsed or implemented. In this article we present the findings of a study in Johannesburg that explored the attitudes and roles of nurses in end-of-life care and organ donation. A total of 273 nurses participated. Most were female and <50 years old. The majority expressed positive attitudes towards both end-of-life care and organ donation, but there was ambiguity as to whether referring patients and families for these services was within nursing scope of practice. The vast majority of participants noted that they would refer patients themselves if there was a mandatory, nationally endorsed referral policy. These findings have implications for clinical practice and policy, and suggest that the formulation and implementation of robust national guidelines should be a priority. Because nurses would follow such guidelines, this might lead to an increase in donor rates and circumvent some uncertainty regarding referral.

Organ transplantation in South Africa (SA) began 50 years ago at the old Johannesburg Hospital in Hillbrow. Since then, advances in surgical technique and immunosuppressive agents have improved recipient and graft survival, so that transplantation is now accepted worldwide as standard of care for end-stage organ failure. In practice, however, access to organ transplantation is limited and inequitable in our country. Transplant services are not uniformly distributed, but rather confined to large urban areas in wealthier provinces. Nor is the service offered at each transplant centre standardised, with many more offering kidney than heart, lung, pancreas and liver transplants. There are also disparities across the state and private sectors. Socioeconomics and geography leave the poor in rural areas most vulnerable to exclusion.

Having said this, we do have highly specialised transplant units that are grossly underutilised owing to persistently low organ-donor rates. Research has repeatedly shown that most South Africans across all population groups support organ donation. However, the public need more culturally and linguistically appropriate information to make informed decisions regarding organ donation.[1-3] Other potential reasons may be a lack of referral of potential donors by hospital staff and their attitudes towards donation. Again, local studies have confirmed that most trainee/qualified nurses and medical students are in favour of organ donation, and their stance is influenced more by education regarding organ donation than gender, cultural identity or ethnicity.[4-6]

So why are our organ-donor rates still so frustratingly low?

Low donation rates have been the focus of many international transplant communities. In countries where this has been successfully prioritised, some common themes emerge. These are: governmental support, comprehensive public education, clear clinical practice guidelines, hospital staff education, an organ procurement transplant co-ordinator in each hospital and a 'required referral' system.[7,8]

'Required referral' means that any terminal patient who fulfils certain criteria must be timeously referred to a transplant co-ordinator for end-of-life care, irrespective of whether this results in organ donation. This may sound simple, but there is often conflict regarding how and when referral should take place. This conflict is understandable. Biomedicine has changed our definitions of death to include concepts such as imminent death, brain death and cardiac death. In addition, organ donation usually occurs in highly charged settings. For example, a ventilated intensive care unit (ICU) patient with a head injury has absent cranial nerve reflexes and a low Glasgow Coma Score, signifying risk of brain death. At what point should we refer a family for an end-of-life discussion? When there is imminent death, before or after testing for brainstem death, or when the attending clinician withdraws active treatment? Referral prior to withdrawal of care may feel unethical for some healthcare professionals. Bearing this in mind, how do the transplant co-ordinators maintain contact with the team? Should they assume a proactive role and call or email the unit daily, or should they join the team on a daily ward round? In the case of referral, who should then refer, the nurse caring for the patient or the primary doctor?!']

In this article we present the findings of a study in Johannesburg that was designed to go beyond the attitudes of nurses and explore end-of-life care and organ donation so that, at least in part, some of these issues may be addressed. In particular, we explored nurses' knowledge of organ donation, and whether they would support clinical practice guidelines for end-of-life care and organ donation. Based on our findings, we discuss the potential implications for clinical practice and legislative regulation of organ donation in SA.

Summary of the study

This study was conducted from July 2015 to March 2016 and was approved by the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) (ref. no. M150334). A total of 273 qualified nurses working in state and private sector ICUs, casualty and high-care departments, as well as two transplant units in Johannesburg, completed a self-administered questionnaire. Participation was similar in both state and private sectors, with an overall response rate of 68.6%. The majority (74.2%) of respondents were registered nurses, of whom 40.1% were ICU trained, and of the remaining staff, 56.5% had at least 1 year of ICU experience. Christianity (69.1%) and African Traditional Religion (16.5%) were the most common religious affiliations,and isiZulu (24.1%), English (13.8%) and Setswana (13.8%) were the most frequently spoken home languages.

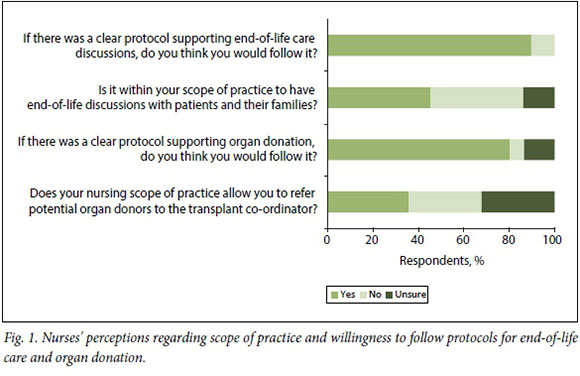

Our findings showed that most nurses (64.2%) were willing to donate their own organs after death. In addition, most nurses (63.2%) felt that their personal beliefs did not influence advice given to patients and families regarding organ donation, and this was independent of employment sector, age and qualification. The majority (85.9%) felt that end-of-life care should be offered to all terminally ill patients and their families, and (79.9%) that identifying these families was the role of the attending doctor. But less than half (47.6%) felt that staff in their unit communicated with families about end-of-life care, and only 45.4% felt that initiating these discussions was within their scope of practice. However, ICU-trained and registered nurses were more confident that this was within their scope of practice than enrolled nurses or nurse assistants. If there was a clear protocol supporting end-of-life discussions, 89.8% of nurses at all levels of training agreed they would follow it (Fig. 1).

When asked about staff attitudes towards organ donation in their units, 36.8% of nurses agreed that staff viewed this positively, while a similar proportion were unsure (38.7%) and the remainder felt staff were negative (24.4%). Most nurses (84.5%) felt that referral for organ donation was the responsibility of the doctor. There was a roughly equal three-way split between nurses agreeing (35.8%), disagreeing (32.1%) and being unsure (32.1%) about whether organ-donor referral was within their scope of practice; ICU-trained and registered nurses felt more certain that organ-donor referral was within their scope of practice than other categories of nurses. As was seen with regards to the questions on end-of- life care, 80.3% of all nurses, irrespective of employment sector, qualification, age or home language, would follow a clear protocol for organ-donor referral (Fig. 1).

Regarding organ procurement, 61.0% of nurses were aware that there was access to a transplant co-ordinator through their hospital, but more nurses in the private sector (70.3%) were aware of this compared with those in the state sector (56.3%). The majority understood that the primary roles of a transplant co-ordinator included facilitating end-of-life care, tracing the family of a potential donor and consenting donor families, reminding staff about organ donation and teaching the community about organ donation.

Nurses' knowledge regarding the supply of organs, access to transplants and legal rights of the donors/next of kin was fair, but there was a significant difference between those in the private sector, who had a better knowledge base, compared with the state sector, as there was with ICU-trained nurses when compared with non-ICU-trained colleagues. Those who were willing to donate their organs after death had better knowledge than those unwilling to donate. Their primary sources of information about organ donation were postgraduate workshops run by transplant co-ordinators, and active participation in the practical care of donors and/or recipients. Media, undergraduate training and exposure at school were considered less useful.

Discussion

This is the first quantitative study that has explored the perceptions of nurses' professional roles in the practice of end-of-life care and organ donation in SA. The results show that overall, nurses support end-of-life care and organ donation, and if there were clinical guidelines clarifying their roles, they would follow them. However, several issues are raised regarding current clinical practice.

Firstly, in this study nurses recognised the need for and supported end-of-life care for all terminal patients. They also acknowledged that more than half of their units did not initiate end-of-life discussions, nor did they feel this was within their scope of practice. Similarly, only one-third of staff felt positive about the referral of potential organ donors, and almost the same proportion were unsure, while most felt this was outside their scope of practice. Understanding scope of practice in such a specialised field of medicine is difficult. Nursing scope of practice is legally defined within a certain set of parameters in SA. However, the specific roles required of nurses are not condensed into an exhaustive list because this would not account for changes in medical technology and procedures.[10] As a result, medical interventions such as organ transplant are not addressed in nursing scope-of-practice guidelines at all. Further compounding this uncertainty is the fact that currently there is no legislation, nor are there any clinical practice guidelines in SA that clarify the role of nurses in end-of-life care and organ donation. This may, in part, be the reason that nurses defer decision-making to the doctor. While the rationale for broad, nonspecific guidelines is understandable, end-of-life and organ donation issues present a unique set of interprofessional challenges, and their efficacy is based on multidisciplinary teamwork.'[11] Without well-defined roles in these processes, nurses' unwillingness to participate is unsurprising.

These types of regulatory issues have been addressed in other countries. In the UK, for example, best-practice guidelines outline the role of nurses, and endorse nurse-led referral of potential donors, provided minimum criteria for referral are met. These guidelines also offer potential avenues for the clinical team to interact with the transplant co-ordinators, which allows organ procurement personnel to engage in a predetermined manner with the primary clinical team. This prevents potential conflict and resistance from the primary clinical team in the referral process. Emphasis is placed on the importance of working as a team, in contrast to decisions and referrals being doctor driven.[9] In addition to being nationally endorsed at governmental level, each hospital in the UK is required to have its own policy in support of end-of-life care and organ donation, and to ensure ongoing education and training for staff in this area. This reinforces the role of each team member, allows staff to feel safe and facilitates the integration of end-of-life care and organ donation as standard daily practice, rather than as something extra that needs to be done.

The second issue relates to education of nurses regarding organ donation. This study shows that knowledge of organ donation at school and in nurses' undergraduate training contributes very little to their knowledge base. Rather, hands-on experience with organ donation once they were practising, and the ongoing efforts of organ procurement teams to promote understanding through informal workshops in hospitals, were much more effective learning opportunities.

The third issue addresses the role of the organ-procurement team, through the transplant co-ordinator. At present, there is no formal training available for nurses who wish to specialise in organ procurement in SA. This prevents nurses from pursuing this area of specialty as a career path, and does not allow for specific training or a clear understanding of their roles. Currently, to work as a transplant co-ordinator in SA, it is generally accepted that ICU training is essential, and while some co-ordinators have completed specialised training overseas, this is not a standard requirement. Part of the success of teams elsewhere has been due to governmental commitment to support the appointment of a transplant co-ordinator in every hospital in the country that has the capacity to participate in organ donation.[7] While one may question the absence of similar governmental policy in SA, it is pertinent to consider whether we would have the capacity to train such staff, should the situation change.

The last issue highlights the lack of standardisation of end-of-life care and referral of potential organ donors. Timeous referral of potential donors is essential to allow the transplant co-ordinator sufficient time to approach the grieving family, obtain consent, support the donor until organ procurement occurs and complete screening tests to ensure donated organs are transplantable. Currently, the referral process for potential organ donors to the procurement team is haphazard. While the attending doctor is responsible for the 'medical' diagnosis of death (brainstem or cardiac), is it appropriate or fair or in the best interests of the patient and their family to lay the sole responsibility for end-of-life care and organ donation entirely in the doctor's hands? Failure to refer compromises the lives of thousands of patients with end-stage organ failure who are on waiting lists, and referral is regarded by some as an ethical obligation.[12] It may be that strongly doctor-centric models of practice are still very common in SA, but they are far less so in Europe and the USA. Could it be that our nurses feel disempowered, or fear recrimination from the attending doctor, rather than feeling part of a team in which their role is respected and valued? Do they fear litigation or consequences from their employer, particularly when there is no hospital policy to support their role? These factors deserve to be explored in future research.

Conclusion

This research adds some insight into nurses' perceptions of their roles in end-of-life care and the referral of potential organ donors. It confirms that by far the majority of nurses would follow nationally endorsed clinical practice guidelines that address these important issues. These guidelines would need to determine definitions of death, criteria for referral for end-of-life care and organ donation, mechanisms of referral to the organ-procurement team, and the associated roles and responsibilities of both doctors and nurses. If nationally endorsed, and implemented at hospital level, this may improve organ-donor rates, and would be an essential precursor to any discussion on 'required referral' for SA. However, this cannot occur without simultaneously addressing the need to formalise the training of transplant co-ordinators within nursing education, and prioritising the lack of public education on organ donation.

Dedication. This paper is dedicated to the memory of Belinda Rossi-Britz.

Acknowledgements. We would like to acknowledge the following: Wits Donald Gordon Medical Centre; and REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) (Vanderbilt University, USA), a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies, providing: (i) an intuitive interface for validated data entry; (ii) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (iii) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (iV) procedures for importing data from external sources.[13]

Author contributions. KC conceptualised and designed the study, consented participants, distributed questionnaires, and planned and edited the final manuscript. HE assisted with study design and provided insight on the final draft. JF assisted with study design and planned and wrote the manuscript. PG conducted the statistical design, piloted the questionnaire and edited the final manuscript.

Funding. We thank Astellas Pharma (Pty) Ltd for funding.

Conflict of interest. None

References

1. Bhengu B, Uys H. Organ donation and transplantation within the Zulu culture. Curationis 2004;27(3):24-33. [ Links ]

2. Pike RE, Odell J, Kahn D. Public attitudes to organ donation in South Africa. S Afr Med J 1993;83(2):91-94. [ Links ]

3. Etheredge HR, Turner RE, Kahn D. Attitudes to organ donation among some urban South African populations remain unchanged: A cross-sectional study (1993 - 2013). S Afr Med J 2014;104(2):133-137. http://dx.doi.org/10.7196%2FSAMJ.7519 [ Links ]

4. Naude A, Nel E, Uys H. Organ donation: Attitude and knowledge of nurses in South Africa. EDTNA ERCA J 2002;28(1):44-48. [ Links ]

5. Gidimisana ND. Knowledge and Attitudes of Undergraduate Nurses towards Organ Donation and Transplantation in a Selected Campus of a College in the Eastern Cape. Cape Town, South Africa: University of Cape Town, 2016. [ Links ]

6. Sobnach S, Borkum M, Millar AJ, et al. Attitudes and beliefs of South African medical students toward organ transplantation. Clin Transplant 2012;26(2):192-198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01449.x [ Links ]

7. Bleakley G. Implementing minimum notification criteria for organ donation in an acute hospital's critical care units. Nurs Crit Care 2010;15(4):185-191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-5153.2009.00385.x [ Links ]

8. Murphy F, Cochran D, Thornton S. Impact of a bereavement and donation service incorporating mandatory 'required referral' on organ donation rates: A model for the implementation of the Organ Donation Taskforce's recommendations. Anaesthesia 2009;64(8):822-828. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2044.2009.05932.x [ Links ]

9. Donor Identification and Referral Strategy Group, National Health Service Blood and Transplant. Timely Identification and Referral of Potential Organ Donors. A strategy for Implementation of Best Practice. National Health Service Blood and Organ Transplant Policy: United Kingdom, 2012. [ Links ]

10. Geyer N. Scope of nurses' practice. Prof Nurs Today 2016;20(1):51-52. [ Links ]

11. Etheredge HR. 'Hey sister! Where's my kidney?' - Exploring ethics and communication in organ transplantation in Gauteng Province, South Africa, 2015. http://hdl.handle.net/10539/21425 (accessed 17 January 2017). [ Links ]

12. Muller E. Organ donation and transplantation in South Africa - An update. CME J 2013;31(6):220-222. [ Links ]

13. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) - a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42(2):377-381. https://doi.org/10,1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

K Crymble

kim.crymble@mediclinic.co.za

Accepted 22 March 2017