Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.107 no.6 Pretoria jun. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2017.v107i6.12356

IN PRACTICE

HEALTHCARE DELIVERY

Audits of oncology units - an effective and pragmatic approach

R P AbrattI, II; D EedesIII; B BaileyIV; C SalmonV; Y GovenderVI; I OelofseVII; H BurgerVIII

IFC Rad Onc; Division of Radiation Oncology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa

IIFC Rad Onc; Independent Clinical Oncology Network, Cape Town, South Africa

IIIFC Rad Onc; Independent Clinical Oncology Network, Cape Town, South Africa

IVBTech; Independent Clinical Oncology Network, Cape Town, South Africa

VBPhysT Hons, MBA; ISIMO Health, Cape Town, South Africa

VIMTech; Equra Health SA, Durban, South Africa

VIIBSc Hons; Equra Health SA, Durban, South Africa

VIIIFC Rad Onc; Division of Radiation Oncology, Tygerberg Hospital and Stellenbosch University, and Division of Radiation Oncology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Audits of oncology units are part of all quality-assurance programmes. However, they do not always come across as pragmatic and helpful to staff.

OBJECTIVE. To report on the results of an online survey on the usefulness and impact of an audit process for oncology units.

METHODS. Staff in oncology units who were part of the audit process completed the audit self-assessment form for the unit. This was followed by a visit to each unit by an assessor, and then subsequent personal contact, usually via telephone. The audit self-assessment document listed quality-assurance measures or items in the physical and functional areas of the oncology unit. There were a total of 153 items included in the audit. The online survey took place in October 2016. The invitation to participate was sent to 59 oncology units at which staff members had completed the audit process.

RESULTS. The online survey was completed by 54 (41%) of the 132 potential respondents. The online survey found that the audit was very or extremely useful in maintaining personal professional standards in 89% of responses. The audit process and feedback was rated as very or extremely satisfactory in 80% and 81%, respectively. The self-assessment audit document was scored by survey respondents as very or extremely practical in 63% of responses. The feedback on the audit was that it was very or extremely helpful in formulating improvement plans in oncology units in 82% of responses. Major and minor changes that occurred as a result of the audit process were reported as 8% and 88%, respectively.

CONCLUSION. The survey findings show that the audit process and its self-assessment document meet the aims of being helpful and pragmatic.

Audits of oncology units are an integral part of their quality-assurance programmes.[1,2] The aim is to maintain standards and accountability and to support continuous quality-improvement programmes.

While all healthcare workers support these aims, audits do not always have positive associations. They may be understood as being antagonistic rather than helpful, and as being bureaucratic rather than pragmatic.

An approach to audits of oncology facilities was developed that aimed to be pragmatic, user-friendly and of a high standard. The aim of this report is to report on a survey of the experience of staff in the various oncology units with this audit process.

Methods

The audit process for oncology facilities

The audit process consisted of three parts. A self-assessment audit document was first completed by staff at the oncology unit. This was followed by a visit by an independent auditor to each unit to review the data in the self-assessment document. Subsequent phone calls and correspondence were used to cross-check the implementation of necessary improvement measures and to help the units to meet these requirements.

The self-assessment audit document was developed by an accountable care organisation (Independent Clinical Oncology Network (ICON)). It was informed by the South African (SA) Department of Health National Core Standards (NCS)[3] and internationally used radiation oncology quality parameters.[4,5]

The audit self-assessment document dealt with four sections in oncology units, each headed by a responsible person. These persons are the practice manager, the oncologist/nurse manager, the pharmacist/chemotherapy nurse manager and the radiation therapist (RTT)/medical physicist. Each section was further divided into functional and physical areas for purposes of the audit.

A multidisciplinary group, which included representatives of all the sections, compiled the quality-assurance items for each section. Items in each area were listed and could be scored as either compliant (C), non-compliant (NC), work-in-progress (WIP) or not assessable (NA). There were 153 quality-assurance items in the audit document.

The self-assessment audit document was endorsed by the SA Society of Clinical and Radiation Oncology in 2015. It is available for use by all oncology units in both the private and public sector. It can be found on the SA Society of Clinical and Radiation Oncology website at http://www.sascro.co.za/downloads/Oncology-Dept-Standard-Audit-Checklist%20-29-Feb-2016.docx (accessed 30 January 2017).

The survey

The questions in the online survey were developed to determine the perception of the staff about the audit process, as well as the practical impact of the audit on the unit. The survey was compiled in a series of meetings by a multidisciplinary team that included oncologists, practice managers, chemotherapy nursing sisters and RTTs.

To be eligible for the survey, respondents were required to have previously been part of the current audit process and to have completed the audit self-assessment form. All respondents could only complete one survey questionnaire, even if they had completed the self-assessment form for more than one section in an oncology unit or had responsibility in more than one oncology unit.

The following ethical criteria were observed in the survey: the anonymity and confidentiality of the participants in the survey were strictly maintained; all potential participants were informed that the results may be published; and those who completed the survey were given a full summary of the findings as soon as they became available. No patients were included. These criteria are acceptable for publication of survey results in Britain (C Blaine, Deputy Head of Content, British Medical Journal (personal communication)).

The first author acknowledges that for such studies in SA, 'it is prudent to obtain ethics approval before the study begins.'[6] The findings are published for the public good, as they will be constructive for quality-improvement programmes.

The survey was undertaken in October 2016 using an online commercial service (Survey Monkey, https://www.surveymonkey.com). Invitations were sent to the staff of 59 oncology units in the private sector. The clinical services provided by these 59 units were as follows: 14 of these units provided a combination of radiotherapy and chemotherapy, 34 units offered only chemotherapy and 11 offered only radiotherapy.

The target number of survey responders was 132. The respondents were blinded to the investigators.

Results

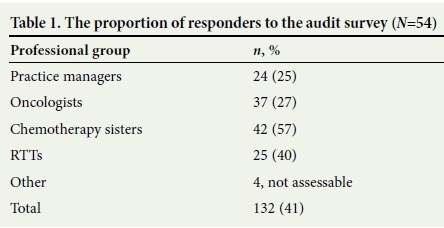

The number of responders to the survey was 54 (41% of the total). The responder rate according to professional groups is shown in Table 1.

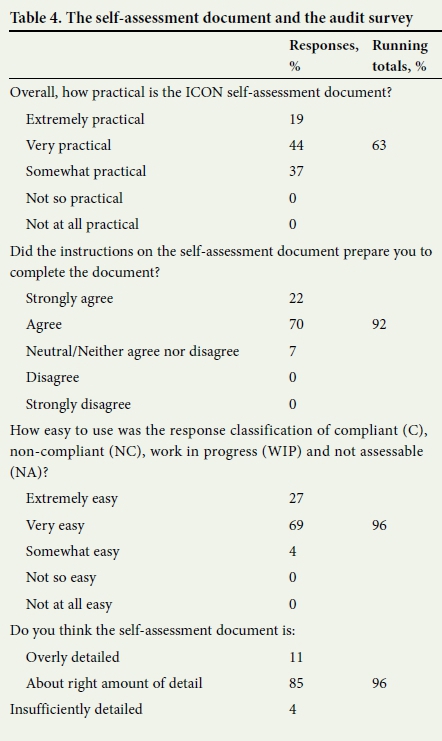

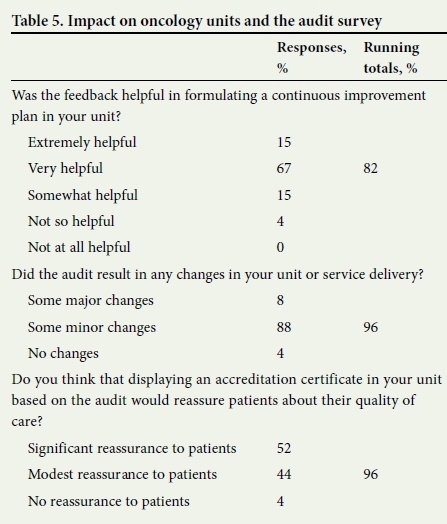

The findings of the survey focusing on the domains for the staff in oncology units, the audit process, the self-assessment document and the impact of the audit are described in Tables 2 - 5. Running totals are given for the sum of the highest two answers for responses with a five-point scale.

Discussion

The NCS tool meets a broad mandate and evaluates health services across seven domains. These are: safety, clinical care, governance, patient experience of care, access to care, infrastructure and environment and public health.

The revised ICON audit was developed using specific productivity principles.[7] This process highlights the principle that the items being measured should be assigned within their physical and functional context rather than according to abstract concepts that apply to multiple different service areas. For example, the section for the pharmacist/chemotherapy nurse manager was divided in the current audit into areas for pharmacy administration, pharmacy equipment and storage, chemotherapy administration area, chemotherapy treatment and the patient's chemotherapy administration records.

The planned follow-up and feedback in order to assist with quality-improvement programmes exceeds the usual practice in auditing facilities.

The online survey was done to assess the perceptions of the staff of the various units about the audit process, the practicality of the audit process and the impact of the audit on unit processes.

The questions were completed by 54 (41%) of 132 potential respondents. This is a high responder rate for online surveys. The highest rates were from the pharmacy/chemotherapy administration and the radiotherapy administration areas at 57% and 40%, respectively. This may be because staff in these sections usually received personal feedback on the audits, although written feedback was given to all sections within the oncology units. A further reason could be that staff within these sections may well have a high level of responsibility for the maintenance of facility standards within oncology units.

It was noted that there was no single person coordinating the survey in 35% of units. It would be advantageous to clearly identify such a person within each unit, who would then work with a centralised quality-assurance committee within the units to facilitate the audit process and to formulate improvement strategies.

The respondents in the survey were very positively disposed to the components of the audit and its practical impact. The need for an audit was appreciated by 96% of respondents. Eighty-nine percent of the oncology unit staff reported that it was very useful or extremely useful in maintaining personal professional standards.

The audit process, including the document, follow-up visit and the feedback by email or telephone was rated by respondents as very or extremely satisfactory by 80% and 81% of respondents, respectively.

The self-assessment document was scored by respondents as very or extremely practical by 67%, and as containing the right amount of detail by 85%.

The impact of the audit was highly rated. The feedback from the survey was that the audit was very helpful or extremely helpful in formulating improvement plans (82% of respondents). Major and minor changes in oncology units occurred in 8% and 88%, respectively.

Limitations

A caveat to the findings is that those respondents who felt most positive may have been more likely to complete the survey than those who felt indifferent to the survey. The respondent rate was 41%, which is relatively high for an online survey. A study of physicians has found that respondents and non-respondents had similar characteristics.[8] The findings in this survey were consistent across professional groups. Further investigation would require extensive individual interviews.

Conclusion

The survey findings show that the respondents have found that this audit process and its self-assessment document meet the aims of being helpful and pragmatic, and they can be useful in the maintenance of standards, accountability and establishing continuous quality-improvement programmes in oncology units.

Acknowledgements. The authors thank Dr E Marias, Dr L Jones, Ms B Wyrley Birch and Ms N Coetzee for their support and help during the course of this study.

Author contributions. All authors have contributed to the design of the study and have reviewed the manuscript.

Funding. None.

Conflicts of interest. R Abratt, D Eedes and B Bailey are employees of the Independent Clinical Oncology Network.

References

1. Quality Assurance Team For Radiation Oncology (QUATRO) International Atomic Energy Agency. Comprehensive Audits of Radiotherapy Practices: A Tool for Quality Improvement. Vienna, 2007. http://www-pub.iaea.org/MTCD/publications/PDF/Pub1297_web.pdf (accessed 30 January 2017). [ Links ]

2. Thwaites DI, Scalliet P, Leer JW, Overgaard J. Quality assurance in radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol 1995;35(1):61-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-8140(95)01549-V [ Links ]

3. National Department of Health, South Africa. National Core Standards for Health Establishments in South Africa. 2011. [ Links ]

4. The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Radiologists (RANZCR), The Faculty of Radiation Oncology (FRO), Australian Institute of Radiography (AIR), The Australian College of Physical cientists and Engineers in Medicine (ACPSEM). Tripartite Radiation Oncology Practice Standards. 2011. http://www.radiationoncology.com.au/supporting-docs/ranzcr-standards (accessed 30 January 2017). [ Links ]

5. Cotttera WG, Dobelbower Jr. RR. Radiation oncology practice accreditation: The American College of Radiation Oncology, Practice Accreditation Program, guidelines and standards. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2005;55(2):93-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.03.002 [ Links ]

6. National Department ofHealth, South Africa. Ethics in Health Research Principles, Processes and Structures. 2015. http://www.nhrec.org.za/docs/Documents/OperationalGuidelinesMinisterialConsentFinalFeb2015.pdf (accessed 30 January 2017). [ Links ]

7. Allen D. Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity. USA: Penguin Books, 2001. [ Links ]

8. Kellerman SE, Herold J. Physician response to surveys. Am J Prev Med 2001;20(1):61-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00258-0 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

R Abratt

Raymond.Abratt@uct.ac.za

Accepted 21 February 2017