Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.107 no.5 Pretoria may. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2017.v107i5.12370

RESEARCH

South African medical students' perceptions and knowledge about antibiotic resistance and appropriate prescribing: Are we providing adequate training to future prescribers?

S WassermanI; S PotgieterII; E ShoulIII; D ConstantIV; A StewartV; M MendelsonVI; T H BoylesVII

IMB ChB, MMed; Division of Infectious Diseases and HIV Medicine, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIMB ChB; Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

IIIMB ChB; Division of Infectious Diseases and HIV Medicine, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IVPhD, MPH; Women's Health Research Unit, School of Public Health and Family Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

VMPH; Clinical Research Centre, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

VIMD, PhD; Division of Infectious Diseases and HIV Medicine, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

VIIMD; Division of Infectious Diseases and HIV Medicine, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Education of medical students has been identified by the World Health Organization as an important aspect of antibiotic resistance (ABR) containment. Surveys from high-income countries consistently reveal that medical students recognise the importance of antibiotic prescribing knowledge, but feel inadequately prepared and require more education on how to make antibiotic choices. The attitudes and knowledge of South African (SA) medical students regarding ABR and antibiotic prescribing have never been evaluated.

OBJECTIVE. To evaluate SA medical students' perceptions, attitudes and knowledge about antibiotic use and resistance, and the perceived quality of education relating to antibiotics and infection.

METHODS. This was a cross-sectional survey of final-year students at three medical schools, using a 26-item self-administered questionnaire. The questionnaires recorded basic demographic information, perceptions about antibiotic use and ABR, sources, quality, and usefulness of current education about antibiotic use, and questions to evaluate knowledge. Hard-copy surveys were administered during whole-class lectures.

RESULTS. A total of 289 of 567 (51%) students completed the survey. Ninety-two percent agreed that antibiotics are overused and 87% agreed that resistance is a significant problem in SA - higher proportions than those who thought that antibiotic overuse (63%) and resistance (61%) are problems in the hospitals where they had worked (p<0.001). Most reported that they would appreciate more education on appropriate use of antibiotics (95%). Only 33% felt confident to prescribe antibiotics, with similar proportions across institutions. Overall, prescribing confidence was associated with the use of antibiotic prescribing guidelines (p=0.003), familiarity with antibiotic stewardship (p=0.012), and more frequent contact with infectious diseases specialists (p<0.001). There was an overall mean correct score of 50% on the knowledge questionnaire, with significant differences between institutions. Students who used antibiotic prescribing guidelines and found their education more useful scored higher on knowledge questionnaires.

CONCLUSION. There are low levels of confidence with regard to antibiotic prescribing among final-year medical students in SA, and most students would like more education in this area. Perceptions that ABR is less of a problem in their local setting may contribute to inappropriate prescribing behaviours. Differences exist between medical schools in knowledge about antibiotic use, with suboptimal scores across institutions. The introduction and use of antibiotic prescribing guidelines and greater contact with specialists in antibiotic prescribing may improve prescribing behaviours.

Antibiotic resistance (ABR) is now an established threat to global health, and inappropriate prescribing behaviours by clinicians have been implicated as a major contributing factor. Antibiotic stewardship is a key intervention to improve prescribing practices at individual and facility levels.[1,2] In South Africa (SA), as elsewhere, antibiotic stewardship programmes have had success in reducing antibiotic consumption.[3] However, the existing antibiotic stewardship infrastructure in SA has important limitations. First, formal stewardship programmes mainly target postgraduate clinicians in hospital settings, and have not reached outpatient and community settings, where the majority of antibiotic prescribing occurs. Second, existing programmes are usually led by infectious diseases physicians, who are a scarce resource in SA and not available in most healthcare settings. Unlike other disciplines, such as oncology, where the use of chemotherapy is restricted to specialists and is tightly controlled, antibiotics are most often prescribed by junior doctors and generalists, regardless of training or knowledge.[4] Additionally, effecting sustained behaviour change around antibiotic prescribing requires an insight into, and an appreciation of, the factors leading to ABR.[5] Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing may result from inadequate preparation at undergraduate level and an under-appreciation of the extent and implications of ABR. It is, therefore, critical to equip clinicians with the necessary confidence and skill in appropriate antibiotic prescribing at an early stage in their careers,[6] and implement interventions to modify perceptions and behaviours. Education of medical students has been identified by the World Health Organization as an important aspect of ABR containment.[7-9] Although formal pharmacology and microbiology lectures are included in medical school curricula, there appears to be a failure to translate this into clinical prescribing practice[10] and a discordance between knowledge and practice.[11] Surveys from high-income countries consistently reveal that medical students recognise the importance of antibiotic prescribing knowledge, but feel inadequately prepared and require more education on how to make antibiotic choices.[11-13] The attitudes and knowledge of SA medical students regarding antibiotic prescribing and resistance have not been evaluated, and no formal analysis has been undertaken of their perceptions of the effectiveness of medical education on these issues. This study aims to identify gaps in medical students' education about antibiotic use to strengthen undergraduate training and ultimately improve prescribing practice.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of final-year students at three medical schools in three different provinces of SA: University of the Witwatersrand (Wits), University of Cape Town (UCT), and University of the Free State (UFS), using a 26-item self-administered questionnaire. The survey assessed perceptions, attitudes and knowledge about antibiotic use and resistance, and the perceived quality of education regarding preparedness to be antibiotic prescribers. The structure and content of the survey were based on those used in previous similar studies,'12,131 and were adapted for our setting by three infectious diseases specialists on the study team. The questionnaires (Supplementary Appendix A*) recorded basic demographic information, perceptions about antibiotic use and resistance, sources, quality, and usefulness of current education about antibiotic use, and included questions to evaluate knowledge. To improve standardisation of the knowledge-based questions, the content was drawn from the widely used South African Antibiotic Stewardship Programme (SAASP) antibiotic prescribing guideline.[14] Depending on the category, there were either single- or multipleanswer responses, which were graded using a 5-point Likert scale. The survey was pilot tested among 13 medical students for readability, length, and relevance before implementation.

For the 2015-year group, hard-copy surveys were administered during whole class lectures; the findings from these responses are reported here. No additional training was provided and no changes to the curriculum were made before or during the survey period. An incentive for participation was offered in the form of a random draw to win an iPad. The study was advertised using direct emails and class announcements and notices. Written informed consent was obtained prior to participation, which was voluntary and anonymous. Ethics approval was obtained from the ethics committee and faculty of each institution (ref. nos: UCT HREC 097/2014; ECUFS 204/2014; Wits HREC M1411113).

Analysis

The participating medical schools were de-identified as A, B, or C to conduct blinded data analysis. Responses from the 5-point Likert scale were condensed into three categories: agree/good, neutral/average, and disagree/poor. Valid percentages were calculated for categorical data, and the mean of correct answers was calculated for the knowledge section. Bivariate associations between categorical variables were tested using binomial probability tests and tests of proportions. Variations between observed and expected proportions were tested for significance with χ2 tests. Mean knowledge scores for two levels of independent variables were compared using f-tests.

Results

Student population

Of a total of 567 final-year students at the three institutions, 289 (51%) completed all or part of the survey. The response rates by institution were 75% (134/179) for UCT, 80% (91/114) for UFS, and 23% (64/274) for Wits. The median age of students was 24 (interquartile range (IQR) 23 - 24) years, and 63% were female. Thirty-four (12%) respond ents had previous degrees.

Perceptions

Respondents' perceptions about the causes and impact of ABR are summarised in Fig. 1. Ninety-two percent of students agreed that antibiotics are overused in SA and 87% agreed that ABR is a significant problem. These proportions were significantly higher than of those respondents who thought that antibiotic overuse (63%) and resistance (61%) are problems in the hospitals where they had worked (p<0.001). Thirty-eight percent were either neutral or disagreed with the statement that 'lack of hand hygiene by healthcare workers contributes to the spread of resistant bacteria'. Almost all students believed that a good knowledge of antibiotics was important for doctors (287/289), and that inappropriate use of antibiotics impacts on resistance (283/289).

Education

Sixty-three percent rated their overall education on antibiotic use as useful or very useful; students from UCT showed a trend towards higher rating (70%) than those from UFS (57%) and Wits (58%) (p=0.07). Most students reported that they would appreciate more education on the appropriate use of antibiotics (95%) and on ABR in general (90%). In terms of the curriculum, 91% of students remembered attending formal lecture(s) on how to diagnose infection, 79% on the indications for starting antibiotics, 82% on the duration of antibiotic therapy, 70% on the indications for intravenous antibiotics, and 89% on the basic principles of infection prevention and control. Students' perceptions of the usefulness of various educational modalities with regard to antibiotic prescribing and resistance, and antibiotic classes and spectrums of activity, are summarised in Table 1. Overall, students reported problem-based learning (PBL) and registrar (resident) rounds as being the least useful (p<0.001).

The most common resources for learning about antibiotic prescribing and resistance were consultants (83%), registrars (85%) and medical textbooks (87%), followed by the use of tablets or smart phones (77%). Forty-seven percent of students reported learning from infectious diseases physicians, and 30% from microbiologists. Less than a third (32%) of students reported using medical journals as a source of education; this number was significantly different between institutions: 48% at Wits compared with 27% at UCT and 26% at UFS (p=0.006). Most respondents (78%) reported using antibiotic guidelines, with similar usage across institutions. Overall, 64% reported being familiar with the term 'antibiotic stewardship', with significantly fewer at UFS compared with UCT and Wits (41% v. 74% and 73%, respectively, p=0.001).

Preparedness

Fig. 2 summarises the students' assessment of preparedness in various aspects of antibiotic prescribing, and Table 2 shows a comparison of these responses between institutions. Thirty-three percent of students felt confident to prescribe antibiotics, with similar proportions across institutions. Prescribing confidence was associated with the use of antibiotic prescribing guidelines (p=0.003), familiarity with the term antibiotic stewardship (p=0.012), and more frequent contact with infectious diseases specialists (p<0.001). The domains for which students felt least prepared were interpretation of antibiograms, knowledge of dosing duration, performing de-escalation, and making the correct antibiotic choice (with reports of good or very good preparedness <50% for each of these). The most frequently suggested measure to improve preparedness of new doctors to prescribe antibiotics was the use of a local handbook or guideline (70%), followed by more contact with infectious diseases specialists (56%), more bedside tutorials (52%), and the use of applications on smart devices (51%). The least popular measures were more time in microbiology (30%), more formal lectures (33%), and the use of computer-based tutorials (18%).

Knowledge

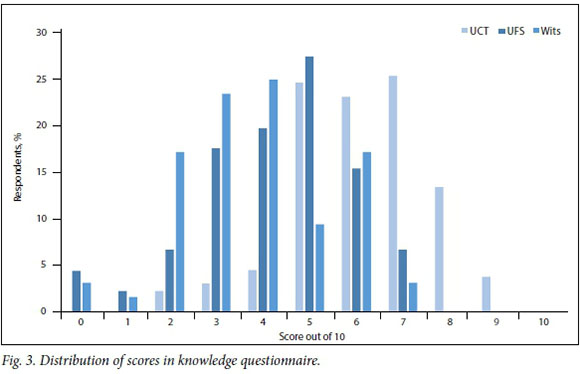

There was an overall mean correct score of 50% on the knowledge questionnaire. Significantly more students from UCT answered correctly compared with those from UFS and Wits (61% v. 42% and 38%, respectively, p=0.001). The distribution of scores for each institution is shown in Fig. 3. The average score for each knowledge vignette is shown in Table 3. Respondents scored well on clinical scenarios relating to the management of community-acquired respiratory and urinary tract infections, but did poorly on questions assessing the management of drip site and Clostridium difficile infection, as well as the spectrum of activity of commonly used antibiotics and resistance mechanisms. Mean knowledge scores were higher among those who reported using antibiotic prescribing guidelines (5.3 (standard deviation 1.9) v. 4.5 (1.7), p=0.001) and those who found their overall education on antibiotics useful or very useful (5.3 (1.9) v. 4.6 (1.7), p=0.002). There was no statistically significant association between knowledge scores and resources used to learn (except, paradoxically, lower scores among those who reported reading medical journals, p=0.025).

Discussion

This is the first formal assessment of SA medical students' perceptions about their preparedness to prescribe antibiotics, and to our knowledge, the only such study reported from Africa. There were three major findings, which are consistent with observations from high-income countries:[11-13,15] (i) a perceived lack of preparedness and confidence to prescribe antibiotics; (ii) a desire for more education in this area; and (iii) inadequate knowledge of basic antibiotic prescribing practice. The bulk of antibiotic prescribing is done by junior doctors and non-special-ists,[4,16] and there are limited opportunities for postgraduate training in antibiotic stewardship, particularly in outpatient practice and non-academic settings.'5,61 Inadequate preparation at medical school may translate into widespread antibiotic misuse and perpetuate antibiotic resistance. Our findings are concerning and serve as a call for inter vention.

In addition to improving knowledge, which is the traditional measure of educational effectiveness, a key objective of antimicrobial stewardship education is to shift attitudes, perceptions, and prescribing behaviours.[6] A worrying finding from our survey was the perception among most medical students that lack of hand hygiene was not an important contributing factor to the spread of ABR. Similar responses were recorded from European medical schools, where a quarter of students felt that hand washing was not important.[12] Although almost all students in our survey recognised the global problem of ABR and the overuse of antibiotics, significantly fewer felt that these were issues in the hospitals where they had worked. This disconnect between personal responsibility and perception of practice has also been recognised among medical students in other settings[13,15] and among senior prescribers.[11,17-19] A lack of prescriber ownership may be a driver of inappropriate prescribing practice.[4] While most students felt prepared to diagnose infection accurately, fewer reported feeling well prepared about deciding when to initiate antibiotic use and in other key domains of antibiotic prescribing. This overconfidence among medical students in making an accurate diagnosis of infection has also been identified elsewhere,[12] and may lead to overprescribing.[20] These findings are important signals that medical education needs to be supplemented with approaches that influence prescribing behaviour. The desire expressed by the majority of students for more education on antibiotic prescribing and ABR in general represents an enabling factor and an educational opportunity.

The students' responses regarding the usefulness of various educational modalities and sources provide some insight into which interventions may be more effective. For example, there appear to be deficiencies in microbiology training at undergraduate level; a minority of students reported learning about prescribing and resistance from microbiologists, together with a poor understanding of antibiograms, and a suboptimal knowledge and preparedness regarding antibiotic spectra of activity and performance of de-escalation. This was reflected by the perception of most students that more time in microbiology would not be a useful measure to improve their preparedness.

Even though most students remembered having attended lectures on key topics, and found these useful, this did not reflect in their knowledge scores. Although passive education, such as class lectures, has a limited impact on improving antibiotic use on its own,[6,16] it is an important method to teach fundamental stewardship principles.[21] Formal lectures were among the least popular suggested methods to improve preparedness for antibiotic prescription, suggesting that other, more active, educational approaches are required to complement traditional passive learning. These approaches, which may include clinical case discussions and interactive e-learning, are generally considered to be more effective for influencing prescribing behaviours.[6] Many medical schools have recognised this and changed their teaching approaches to PBL, where clinical scenarios are facilitated by clinicians in student-led sessions. Interestingly, these sessions were rated as the least useful tools for learning across medical schools, and computer-based tutorials were unpopular modalities to improve preparedness. Similarly, registrar interaction (a common learning resource that usually takes place in the wards and can therefore be considered an active form of learning) was not felt to be a useful source of education on both antibiotic prescribing and ABR principles. There was significant heterogeneity in this assessment between institutions, possibly reflecting differing levels of competence of registrars, the degree of engagement with undergraduate students, and the content and design of these interactions. A US-based study showed that prescribing advice from multidisciplinary antibiotic management teams resulted in more appropriate antibiotic prescribing compared with input from residents alone;[22] this approach could potentially be applied and evaluated in medical student ABR and antibiotic prescribing training. There were also significant differences in overall knowledge scores between the three SA medical schools, suggesting that content and methods of education have an impact on antibiotic prescribing. The development of standardised curricula and teaching methodology for antibiotic stewardship at undergraduate level, re-evaluating the role of PBL, and enhancing the content and structure of e-learning platforms should be considered to facilitate an outcome-based approach to antibiotic prescribing.[23]

A number of enabling factors were identified from this survey. Antibiotic prescribing guidelines were reportedly used by most respondents, which was associated with both prescribing confidence and higher knowledge scores; readiness to consult national guidelines has also been found to be an enabler in other settings.[24] Contact with infectious diseases specialists as a source of learning about antibiotic prescribing and familiarity with the term antibiotic stewardship were independently associated with prescribing confidence. It may therefore be beneficial from an educational point of view to promote the use of local prescribing guidelines and to prioritise time in the curriculum for infectious diseases training, focusing on antibiotic stewardship practices, particularly because fewer than half of the students reported learning from infectious diseases specialists and less than two-thirds reported being familiar with the term antibiotic stewardship. Some medical schools have recognised this and have begun to develop and implement specific antimicrobial stewardship curricula.[16,25]

Our multicentre survey had a similar sample size and a relatively high response rate compared with other settings (three previous studies involving medical students had response rates between ~30%[12,15] and 61%[13]). The number of respondents at Wits was low, but the poor performance in knowledge scores in this group suggests that the degree of response bias (which would have tended towards more interested and higher-performing students) was limited. The external validity of the study is supported by the fairly consistent responses between medical schools in our survey, and those from published reports from other countries.[12,13,15] Overall, knowledge levels could be considered moderate to poor, and findings with regard to significant associations should be interpreted with caution. Because of the inclusion of three diverse and geographically distant institutions, our findings are likely to be generalisable to other SA and African medical schools. However, any heterogeneity in responses or knowledge scores may be related to different pedagogy, which was not assessed. A situational analysis of national antibiotic education at medical schools is planned, with a view to developing a standardised curriculum.[6,16]

In summary, this survey of the knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions of final-year SA medical students of antibiotic use and resistance has exposed training gaps and raises a number of important concerns about the preparedness of our future antibiotic prescribers. The findings of this study should be used to inform and plan relevant outcomes-based undergraduate curricula, so that every medical graduate emerges as a stewardship champion.

*Supplemental material. Supplementary Appendix A is available from the corresponding author on request.

Acknowledgements. None.

Author contributions. SW designed the study, wrote the protocol, collected data, performed the analysis, and wrote the manuscript. SP and ES collected data. DC performed the analysis. AS managed the database and contributed to the analysis. MM reviewed the protocol and manuscript. TB collected data and reviewed the protocol and manuscript.

Funding. This study was funded by a research grant from the Federation of Infectious Diseases Societies of Southern Africa and GlaxoSmithKline.

Conflicts of interest. None.

References

1. Davey P, Brown E, Charani E, et al. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices for hospital inpatients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;(4):CD003543. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD003543.pub3 [ Links ]

2. Arnold SR, Straus SE. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices in ambulatory care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4):CD003539. [ Links ]

3. Boyles TH, Whitelaw A, Bamford C, et al. Antibiotic stewardship ward rounds and a dedicated prescription chart reduce antibiotic consumption and pharmacy costs without affecting inpatient mortality or re- admission rates. PloS ONE 2013;8(12):e79747. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0079747 [ Links ]

4. Charani E, Cooke J, Holmes A. Antibiotic stewardship programmes. What's missing? J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65(11):2275-2277. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkq357 [ Links ]

5. Charani E, Castro-Sanchez E, Holmes A. The role of behavior change in antimicrobial stewardship. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2014;28(2):169-175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2014.01.004 [ Links ]

6. Ohl CA, Luther VP. Health care provider education as a tool to enhance antibiotic stewardship practices. Infect Dis Clin N Am 2014;28(2):177-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2014.02.001 [ Links ]

7. World Health Organization. WHO Global Strategy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance. Geneva: WHO, 2001. [ Links ]

8. World Health Organization. The Evolving Threat of Antimicrobial Resistance. Options for Action. Geneva: WHO, 2012. [ Links ]

9. World Health Organization. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. Geneva: WHO, 2015. [ Links ]

10. Eyal L, Cohen R. Preparation for clinical practice: A survey of medical students' and graduates' perceptions of the effectiveness of their medical school curriculum. Med Teach 2006;28(6):e162-e170. [ Links ]

11. Scaioli G, Gualano MR, Gili R, Masucci S, Bert F, Siliquini R. Antibiotic use: A cross-sectional survey assessing the knowledge, attitudes and practices amongst students of a school of medicine in Italy. PloS ONE 2015;10(4):e0122476. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0122476 [ Links ]

12. Dyar OJ, Pulcini C, Howard P, Nathwani D. European medical students: A first multicentre study of knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014;69(3):842-846. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkt440 [ Links ]

13. Abbo LM, Cosgrove SE, Pottinger PS, et al. Medical students' perceptions and knowledge about antimicrobial stewardship: How are we educating our future prescribers? Clin Infect Dis 2013;57(5):631-638. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cit370 [ Links ]

14. Wasserman S, Boyles T, Mendelson M. A Pocket Guide to Antibiotic Prescribing for Adults in South Africa. Cape Town: Antibiotic Stewardship Programme, 2015. [ Links ]

15. Minen MT, Duquaine D, Marx MA, Weiss D. A survey of knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs of medical students concerning antimicrobial use and resistance. Microb Drug Resist 2010;16(4):285-289. https://doi.org/10.1089/mdr.2010.0009 [ Links ]

16. Pulcini C, Gyssens IC. How to educate prescribers in antimicrobial stewardship practices. Virulence 2013;4(2):192-202. https://doi.org/10.4161/viru.23706 [ Links ]

17. Abbo L, Sinkowitz-Cochran R, Smith L, et al. Faculty and resident physicians' attitudes, perceptions, and knowledge about antimicrobial use and resistance. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2011;32(7):714-718. https://doi.org/10.1086/660761 [ Links ]

18. Guerra CM, Pereira CA, Neves Neto AR, Cardo DM, Correa L. Physicians' perceptions, beliefs, attitudes, and knowledge concerning antimicrobial resistance in a Brazilian teaching hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 200738(12):1411-1414. https://doi.org/10.1086/523278 [ Links ]

19. McCullough AR, Rathbone J, Parekh S, Hoffmann TC, del Mar CB. Not in my backyard: A systematic review of clinicians' knowledge and beliefs about antibiotic resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015;70(9):2465-2473. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkv164 [ Links ]

20. Pulcini C, Cua E, Lieutier F, Landraud L, Dellamonica P, Roger PM. Antibiotic misuse: A prospective clinical audit in a French university hospital. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2007;26(4):277-280. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-007-0277-5 [ Links ]

21. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis 2016;62(10):e51-e77. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw118 [ Links ]

22. Gross R, Morgan AS, Kinky DE, Weiner M, Gibson GA, Fishman NO. Impact of a hospital- based antimicrobial management program on clinical and economic outcomes. Clin Infect Dis 2001;33(3):289-295. https://doi.org/10.1086/321880 [ Links ]

23. Davenport LA, Davey PG, Ker JS. An outcome-based approach for teaching prudent antimicrobial prescribing to undergraduate medical students: Report of a Working Party of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. J Antimicrob Chemother 2005;56(1):196-203. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dki126 [ Links ]

24. Chaves NJ, Cheng AC, Runnegar N, Kirschner J, Lee T, Buising K. Analysis of knowledge and attitude surveys to identify barriers and enablers of appropriate antimicrobial prescribing in three Australian tertiary hospitals. Intern Med J 2014;44(6):568-574. [ Links ]

25. Luther VP, Ohl CA, Hicks LA. Antimicrobial stewardship education for medical students. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57(9):1366. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cit480 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

S Wasserman

sean.wasserman@gmail.com

Accepted 17 March 2017.