Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.107 no.3 Pretoria mar. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2017.v107i3.12365

CME

Prevention of ingestion injuries in children

M ArnoldI; A B van AsII; A NumanogluIII

IMB ChB, DCH (SA), FCPaedSurg (SA), MMed (PaedSurg); Division of Paediatric Surgery, Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital and University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIMB ChB, MMed, MBA, FCS PhD; Childsafe, Cape Town; and Trauma Unit, Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital and Division of Paediatric Surgery, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIIMB ChB, FCS (SA); Division of Paediatric Surgery, Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital and University of Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Accidental caustic and foreign body ingestion by young children lead to a high number of emergency department visits, especially in lower- and middle-income countries. Some of these cause minimal tissue injury or pass spontaneously and uneventfully through the gastrointestinal tract; others may cause major morbidity, or rarely mortality. Increased primary prevention of ingestion through community awareness and vigilant childcare in addition to legislative steps to ensure a safe environment for these vulnerable members of society are needed. Secondary prevention of long-term sequelae through timely and appropriate assessment and referral for endoscopy, laparotomy or other treatments can limit morbidity where primary prevention fails. Basic guidelines for management principles are suggested. Social lobby is required to further reform commercial risks to children in addition to creating caregiver awareness of common environmental hazards, particularly in developing countries such as South Africa.

Swallowing of non-food substances is common in toddlers and the preschool age group. Coin ingestion alone has been reported in as many as 4% of children, with 15% of their parents seeking healthcare.[1] Caustic ingestion affects 5 - 518/100 000 people per year, largely in less industrialised nations.[2,3] Distress and a healthcare consultation also occasionally result from choking on age-inappropriate food items (typically hard sweets or large chunks of meat) or bones (especially fish bones[4]), and accidental medication ingestion. At Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital, nearly two of three ingested foreign bodies require endoscopic or surgical removal.[5] Endoscopic grading of injury under general anaesthesia is required in 40% of children who present with caustic ingestion.[6] Ingestion of multiple magnets results in bowel perforations in at least half of children affected.[7]Primary prevention through education and awareness is crucial to reduce the substantial healthcare burden that such incidents present.

The majority of these accidental ingestions occur in the home and nearby areas.[8] Conditions that carry an increased risk of ingestion/ aspiration include attention-deficit hyperactivity syndrome,[9] low levels of parental education,[9,10] young mothers,[8] lack of parental supervision,[8] and rural abode.[11] Male gender predominance is an inconstant finding.[5,9,12-14] Curiosity, exploration of the developing oral phase, the child's inexperience and limited understanding of the environment combined with inadequate caregiver supervision put children under-5[15] at the highest risk of injury from ingested foreign bodies and caustic substances, with a peak incidence at 3 years of age.[5]

A child may present acutely with peri-oral inflammation, dysphagia, drooling, cough, stridor, hoarseness, vomiting or signs of peritonitis. A history of such ingestion may be absent, as ingestion is witnessed in as few as a quarter of all cases,[16] making timely diagnosis and treatment challenging. Peri-oral burns may cause dysphagia and drooling lasting a few hours to weeks. These external signs do not reliably predict oesophageal penetration. Other symptoms include respiratory distress, e.g. from ingestion of volatile agents (e.g. paraffin, hydrocarbons), which may require temporary oxygen support. Full-thickness oesophageal necrosis with subsequent mediastinitis and gastric necrosis with perforation and peritonitis fortunately occur very rarely in children, as intake is usually accidental, substances are not very potent and volumes ingested are thus usually limited by the unpleasant taste.

Household cleaning agents are the most common causative chemical agents, usually because of unsafe storage or use while small children are ill-advisedly allowed in the vicinity. The most commonly ingested chemical is an oxidising agent, such as peroxide or chloride bleach, with domestically retailed concentrations causing only superficial redness and mild oedema. These are therefore not a major risk factor for oesophageal strictures; nevertheless, they result in a significant number of visits to emergency departments although more than symptomatic treatment is usually not required.[12] More concentrated agents used in industrial or agricultural contexts may be ingested, particularly in rural areas.[11]

Complications

Ingestion of a strong alkali (pH >11.5), strong acid (pH <2) or oxidising agent, and mixtures of these, will cause chemical burns in 20 - 40% of children.[17,18] Injury depends on the chemical concentration and volume, the tissue surface area and the duration of exposure. Among the most common serious long-term sequelae is oesophageal stricture formation (7 - 25%),[12,17] which occurs when submucosal penetration of the burn involves >50% of the lumen.

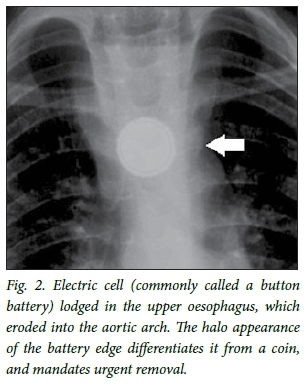

Foreign body perforation and/or obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) typically occurs proximal to normal anatomical narrowing, i.e. (i) the cricopharynx, which is the narrowest part of the child's upper GIT (Fig. 1); (ii) the upper third of the oesophagus, where the left main bronchus and aortic arch cross anteriorly with the vertebral bodies posteriorly (Fig. 2); (iii) the oesophagogastric junction (lower oesophageal sphincter); (iv) the pylorus (Fig. 3); (v) the duodenum at the ligament of Treitz; and (vi) the ileocaecal valve.

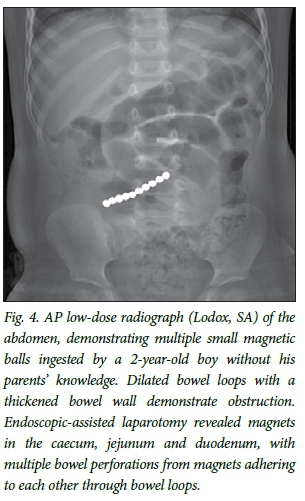

Dangerous ingested foreign bodies include sharp objects that can penetrate the GIT, and blunt objects that may cause partial or complete GIT obstruction and pressure necrosis. Ingestion of >2 magnets can rapidly cause entero-enteric fistulas (Fig. 4), with 85% requiring removal by means of endoscopy, laparoscopy or laparotomy.[19] Electric disc cells (commonly known as button batteries) can cause focal oesophageal burns within an hour in animal studies, while residual activity in used and discarded batteries can still cause significant hydrolysis of tissue.[20] If the narrow negative pole lies anteriorly, risk of perforation with mediastinitis, trachea-oesophageal fistula formation, erosion into great mediastinal vessels (e.g. oesophago-aortic fistulas) and long-term oesophageal stricture formation escalate significantly, especially when extraction is delayed >15 hours after ingestion.[21-23]

Coins remain the most commonly ingested foreign body[5,24] locally and internationally, followed by other plastic and metal objects, especially toy parts. Most (>80%) round objects such as coins, marbles and button batteries are likely to pass through the rest of the GIT spontaneously and uneventfully if they have traversed the cricopha-rynx.[25,26] Fortunately, most foreign bodies (>80%) are radio-opaque.[5,16] Fluoroscopy and occasionally sonography may be useful to detect radiolucent objects, but a low index of suspicion is required for endoscopic evaluation in these cases.

Oesophageal motility and patency may be impaired by previous oesophageal surgery (e.g. oesophageal atresia repair, peptic or caustic stricture dilations and gastric fundo-plication) and increase the risk of a food bolus (notably meat or fibrous fruit, such as citrus) or a foreign body impacting in the oesophagus and causing dysphagia and regurgitation of food. Prolonged impaction of an unrecognised foreign body in this context can aggravate existing oesophageal strictures through pressure necrosis.

Preventive strategies

Public education about the importance of appropriate supervision of small children and the risks imposed in the environment is most important. Public health awareness campaigns using various media are also required to lobby governments to legislate appropriate safety regulations locally.

Lobbying has led to the development and implementation of protective legislation in developed countries. While South Africa (SA) has benefited from legislation overseas, with a trickle-down effect into our local markets, consumers remain vulnerable to less scrupulous manufacturers.While this has had positive spin-offs in SA, with many local companies voluntarily implementing these steps, legislation and enforcement in SA remain limited. Examples include the following:

• Child-proof bottle tops, requiring application of focal pressure in addition to unscrewing the cap, and spray-bottle safety catches on household detergents.

• Limitation on pH of detergents marketed for domestic use.

• Restriction of toys marketed for children <3 years old to a minimum of 3 cm in diameter.

• Secure battery compartments for motorised toys and hearing aidsJ[18]

• Package labelling requirements, e.g. regarding content of chemicals in household use, associated health risks with ingestion, and first-aid advice, including poison centre contact details; warning on packaging of any smaller object to prevent access by children <3 years because of aspiration or swallowing risk.

• Dangerous product recall, e.g. of small (~3 - 5 mm diameter), strong rare-earth (neodymium) balls marketed as 'executive' toys (Fig. 4) in the USA.[19,27]

Examples of unresolved challenges to primary prevention locally and elsewhere include:

• Ongoing household use of strong industrial-strength caustic agents, often illegally sold or decanted and stored in nondescript containers or recycled cold-drink containers, is of great concern. Thirsty children may seek these out or be given these by unsuspecting older siblings, particularly in hot weather, with devastating consequences.

• Marketing, using brightly coloured packaging, has brought new risks to the fore in the past few decades, e.g. automated dishwasher detergent pods, which have caused an upsurge in associated caustic oesophageal injuries in developed countries,[28] although fortunately significant injury occurs in <5% of cases.[2]

Partnership with civil society to identify and mitigate the risks posed to children by these common environmental exposures is crucial. Organisations such as the Child Accident Prevention Foundation of Southern Africa (Childsafe) have been highly instrumental in promoting protective legislation and community awareness. Acknowledgement of the vulnerability of children and the creation of a community culture of protection have consequently grown significantly.

Creative resolutions to risks exist, but require social lobby of manufacturers, retailers and government to promote implementation of suitable marketing innovations and legislative reforms. Traditional print and social media activism remains a relatively under-tapped resource in this regard. For example, retailers of magnet toys could be encouraged to enclose them in a malleable child-proof outer shell. Some retail stores have taken the initiative to promote recycling of high-voltage lithium-ion electric cells; such initiatives could be expanded to include a safety campaign regarding disposal of all discharged used batteries. Warnings of the hazards of accidental swallowing of 'mouthed' small non-food objects by young children could be emphasised in the national Road to Health booklet provided to all children in the government sector and at clinic visits.

Major consequences of ingestion injuries are rare (<1%),[5] but children may incur major morbidity (e.g. tracheostomy, emergency thoracotomy, multiple oesophageal stricture dilatations, oesophageal replacement procedures, and bowel resection) and even mortality as a result. Secondary prevention of sequelae of caustic ingestion by caregivers and healthcare providers includes awareness of the risks posed by various items and agents, and timeous and appropriate removal of the object where indicated, follow-up, or other treatment. A summary of important common agents of ingestion injuries and a brief guideline to their associated management are given Table 1. Early consultation with the nearest poison call centre and tertiary paediatric institution allows identification of the nature of potentially harmful chemicals and appropriate care.

Conclusion

Ingestion injuries remain extremely common in developing countries, unlike some countries in the developed world, where progressive legislation and community awareness foster a culture of vigilance against the risks of gastrointestinal injury in children by accidental injury by non-food substances. These highly preventable injuries are an unnecessary healthcare burden. Limitation of risk factors is achievable with partnership by government, health authorities and non-governmental agencies to identify potential hazards, legislate against commercial risks and warn the public about how these injuries occur.

REFERENCES

1. Conners GP, Chamberlain JM, Weiner PR. Pediatric coin ingestion: A home-based survey. Am J Emerg Med 1995:13(6):638-640. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0735-6757(95)90047-0 [ Links ]

2. Christesen HB. Epidemiology and prevention of caustic ingestion in children. Acta Paed 1994;83(2):212-215. [ Links ]

3. Othman N, Kendrick D. Epidemiology of burn injuries in the East Mediterranean Region: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2010:10(1):83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-83 [ Links ]

4. Lim CW, Park MH, Do HJ, et al. Factors associated with removal of impacted fishbone in children, suspected ingestion. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 2016:19(3):168-174. http://dx.doi.org/10.5223/pghn.2016.19.3.168 [ Links ]

5. Van As AB, du Toit N, Wallis L, et al. The South African experience with ingestion injury in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2003:67(Suppl 1):S175-S178. http://dx.doi.org/10.17140/EMOJ-1-105 [ Links ]

6. Janssen TL, van Dijk M, van As AB, et al. Cost-effectiveness of the sucralfate technetium 99m isotope- labelled esophagal scan to assess esophageal injury in children after caustic ingestion. Emerg Med Open J 2015:1(1):17-21. [ Links ]

7. Waters AM, Teitelbaum DH, Thorne V, et al. Surgical management and morbidity of pediatric magnet ingestions. J Surg Res 2015:199(1):137-140. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2015.04.007 [ Links ]

8. Sanchez-Ramirez CA, Larrosa-Haro A, Vasquez-Garibay EM, et al. Socio-demographic factors associated with caustic substance ingestion in children and adolescents. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2012:76(2):253-256. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.11.015 [ Links ]

9. Cakmak M, Göllü G, Boybeyi Ö, et al. Cognitive and behavioural aspects of children with caustic ingestion. J Pediatr Surg 2015:50(4):540-542. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.10.052 [ Links ]

10. Sarioglu-Buke A, Corduk N, Atesci F, et al. A different aspect of corrosive ingestion in children: Socio-demographic characteristics and effect of family functioning. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2006:70(10):1791-1798. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.06.005 [ Links ]

11. Neidich G. Ingestion of caustic alkali farm products. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutrition 1993:16(1):75-77. [ Links ]

12. Karaman I, Koç O, Karaman A, et al. Evaluation of 968 children with corrosive substance ingestion. Indian J Crit Care Med 2015:19(12):714-718. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0972-5229.171377 [ Links ]

13. Riffat F, Cheng A. Pediatric caustic ingestion: 50 consecutive cases and a review of the literature. Diseases Esofagus 2009:22(1):89-94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2050.2008.00867.x [ Links ]

14. Eskander AE, Sawires HK, Ebeid BA. Foreign-body ingestion in Egyptian children: A 10-year experience of endoscopic intervention in a tertiary hospital. Minerva Pediatr 2016. [ Links ]

15. Rafeey M, Ghojazadeh M, Mehdizadeh A, et al. Intercontinental comparison of caustic ingestion in children. Korean J Pediatr 2015:58(12):491. http://dx.doi.org/10.3345/kjp.2015.58.12.49 [ Links ]

16. Sink JR,Kitsko DJ, Mehta DK, et al. Diagnosis of pediatric foreign body ingestion: Clinical presentation, physical examination and radiologic findings. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2016:125(4):342-350. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0003489415611128 [ Links ]

17. Tiryaki T, Livanelioglu Z, Atayurt H. Early bougienage for the relief of stricture formation following caustic esophageal burns. Pediatr Surg Int 2005:21(2):78-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00383-004-1331-3 [ Links ]

18. Millar AJ, Cox SG. Caustic injury of the oesophagus. Pediatr Surg Int 2015:31(2):111-21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00383-014-3642-3 [ Links ]

19. Kramer RE, Lerner DG, Lin T, et al. Management of ingested foreign bodies in children: A clinical report of the NASPGHAN Endoscopy Committee. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutrition 2015:60(4):562-574. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/mpg.0000000000000729 [ Links ]

20. Jatana KR, Litovitz T, Reilly JS, et al. Pediatric button battery injuries: 2013 task force update. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2013:77(9):1392-1399. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.06.006 [ Links ]

21. Ettyreddy AR, Georg MW, Chi DH. Button battery injuries in the pediatric aerodigestive tract. Ear Nose Throat J 2015:94(12):486-493. [ Links ]

22. Buttazzoni E, Gregori D, Paoli B, et al. Symptoms associated with button batteries injuries in children: An epidemiological review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 2015:79(12):2200-2207. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.10.003 [ Links ]

23. Leinwand K, Brumbaugh DE, Kramer RE. Button battery ingestion in children: A paradigm for management of severe pediatric foreign body ingestions. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2016:26(1):99-118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.giec.2015.08.003 [ Links ]

24. Panieri E, Bass DH. The management of ingested foreign bodies in children: A review of 663 cases. Eur J Emerg Med 1995:2(2):83-87. [ Links ]

25. Pugmire BS, Lin TK, Pentiuk S, et al. Imaging button battery ingestions and insertions in children: A 15- year single center review. Pediatr Radiol 2017:47(2):178-185. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00247-016-3751-3 [ Links ]

26. Litovitz T, Whitaker N, Clark L. Preventing battery ingestions: An analysis of 8648 cases. Pediatrics 2010:125(6):1178-1183. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-3038 [ Links ]

27. Alfonzo MJ, Baum CR. Magnetic foreign body ingestions. Pediatr Emerg Care 2016:32(10):698-702. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000927 [ Links ]

28. Nuutinen M, Uhari M, Karvali T. Consequences of caustic ingestions in children. Acta Paediatr 1994:83(11):1200-1205. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.1994.tb18281.x [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

A B van As

sebastian.vanas@uct.ac.za