Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.107 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2017

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2017.v107i1.11345

RESEARCH

Supernumerary registrar experience at the University of Cape Town, South Africa

S PeerI; S A BurrowsII; N MankahlaIII; J J FaganIV

IMB BCh, FC Orl(SA), MMed (Otol); Division of Otolaryngology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIMBBS, FRCS (ORL-HNS); Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital, UK

IIIMB ChB, FC Neurosurg (SA); Division of Neurosurgery, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IVMB ChB, FCS (SA), MMed (Otol); Division of Otolaryngology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Despite supernumerary registrars (SNRs) being hosted in South African (SA) training programmes, there are no reports of their experience.

OBJECTIVES. To evaluate the experience of SNRs at the University of Cape Town, SA, and the experience of SNRs from the perspective of SA registrars (SARs).

METHODS. SNRs and SARs completed an online survey in 2012.

RESULTS. Seventy-three registrars responded; 42 were SARs and 31 were SNRs. Of the SNRs 47.8% were self-funded, 17.4% were funded through private organisations, and 34.8% were funded by governments. Average annual income was ZAR102 349 (range ZAR680 -460 000). Funding was considered insufficient by 61.0%. Eighty-seven percent intended to return to their home countries. Personal sacrifices were deemed worthwhile from academic (81.8%) and social (54.5%) perspectives, but not financially (33.3%). Only a small majority were satisfied with the orientation provided and with assimilation into their departments. Almost half experienced challenges relating to cultural and social integration. Almost all SARs supported having SNRs. SNRs reported xenophobia from patients (23.8%) and colleagues (47.8%), and felt disadvantaged in terms of learning opportunities, academic support and on-call allocations.

CONCLUSIONS. SNRs are fee-paying students and should enjoy academic and teaching support equal to that received by SARs. Both the university and the teaching hospitals must take steps to improve the integration of SNRs and ensure that they receive equal access to academic support and clinical teaching, and also need to take an interest in their financial wellbeing. Of particular concern are perceptions of xenophobia from SA medical colleagues.

Supernumerary registrars (SNRs) are non-South African (SA) registrars (residents) historically considered more than the number required in training programmes.[1] They constitute approximately 25% of the registrar workforce at major teaching hospitals locally (Supernumerary Registrar Masters of Medicine Enrolment List 2012, Postgraduate Medical Education Office, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town - unpublished). SNRs are not locally remunerated.

Most SNRs originate from African countries with limited or no access to specialist training.[2] On completion of their training, they return to their home country with clinical and academic experience to expand existing specialist services or create units providing specialised care. They may be the first in their country or town with a specialised skill set and the ability to provide much-needed clinical, managerial and teaching services.[3]

Reports of difficulties around registration with the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) and with obtaining work permits and visas, financial constraints and social barriers are some of the challenges that continue to plague SNRs. Despite the longstanding and accepted practice of hosting supernumerary doctors in SA training programmes, there have been no published reports of their experience.

Objectives

To evaluate the experience of SNRs enrolled in clinical medical masters programmes at the University of Cape Town (UCT) and working in the teaching hospitals affiliated to UCT. We also evaluated the experience of SNRs from the perspective of SA registrars (SARs).

Methods

SNRs and SARs in all medical specialties were invited by email to participate in an online survey created through Survey Monkey. Questions were related to funding, integration, xenophobia, allocation of registrar duties and future plans. Participation was voluntary, and the identities of participants remained anonymous so that it would not impact on their careers. Completion of the questionnaire implied consent. Data collected from the two registrar groups were comparatively analysed. Approval for the study was obtained from the UCT Human Research Ethics Committee prior to its commencement (HREC/REF: 095/2013).

Results

The survey was conducted in 2012 over a period of 3 months. Two hundred and eighty registrars were invited to participate; 68 were SNRs. Seventy-three registrars responded (26.1% response rate), of whom 42 (57.6%) were SARs and 31 (42.5%) SNRs.

Responses to questions for SNRs only

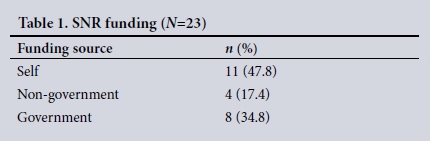

Sources of SNR funding (Table 1) (response rate 74.2%). Of the SNRs, 47.8% were self-funded, 17.4% (4/23) were funded through private organisations (e.g. non-governmental organisations), and 34.8% were funded by their own governments.

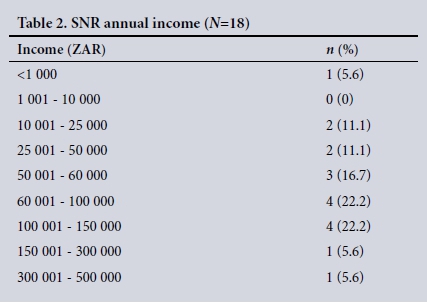

Annual income (Table 2) (response rate 58.1%). The average annual income was ZAR102 349 (range ZAR680 - 460 000). Funding was considered insufficient by 61.0% of SNRs.

SNRs,future plans (Table 3) (response rate 74.2%). Of the SNRs, 87.0% intended to return to their home countries, most planning to work in the public healthcare sector there. More than half (57.1%) did not plan to return to SA for fellowship training. Thirty percent wished to remain in SA - half of these planned to stay for a short period of time before returning home, and the other half intended to stay in SA permanently.

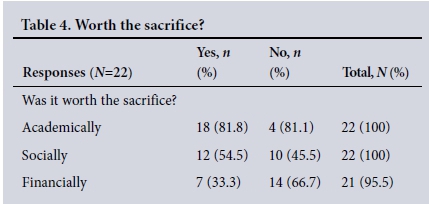

Is SNR training worthwhile? (Table 4) (response rate 71.0%). The sacrifices that were required to obtain a specialist qualification were deemed to be worthwhile from academic (81.8%) and social (54.5%) perspectives, but not from a financial perspective (33.3%).

Responses to questions to both SNR and sAR groups Integration into work environment (Table 5). Only a small majority of SNRs were satisfied with the orientation provided and their assimilation into their departments. Almost 50% experienced challenges relating to cultural and social integration. SARs had a more optimistic view of efforts made to integrate SNRs into the departments, but were of the opinion that nurses were less welcoming than other staff to SNRs. Almost all SARs (94.3%) supported having SNRs in the training programmes.

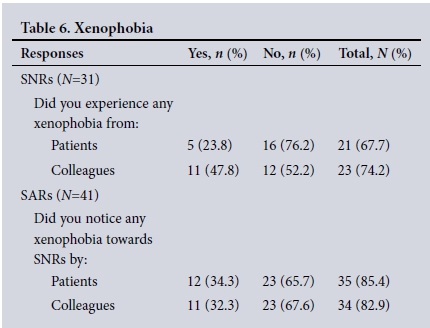

Xenophobia (Table 6). The perception of SNRs that they were subject to xenophobia from patients (23.8%) and colleagues (47.8%) is supported by similar observations reported by a third of SARs.

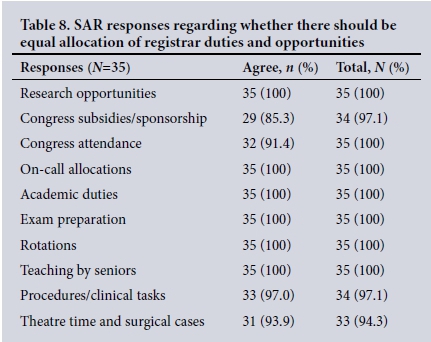

Registrar duties and opportunities (Tables 7 and 8). From the data in Table 7, it is apparent that SNRs felt disadvantaged in relation to the allocation of learning opportunities, academic support and on-call allocations. Their sense of being disadvantaged was very different from the perception of their SA colleagues, who believed that SNRs were being treated equally. Surprisingly, some SARs believed that SNRs should not enjoy the same learning and academic support, despite their being fee-paying students (Table 8).

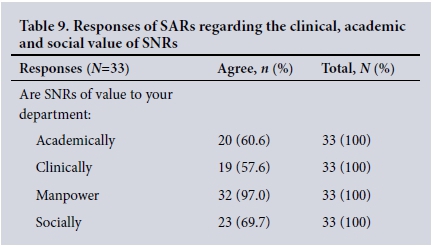

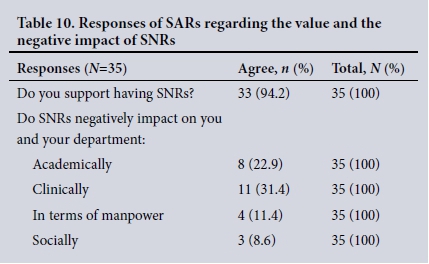

Clinical and academic value of SNRs (Tables 9 and 10). The responses of SARs regarding the value of SNRs in terms of academic contribution and providing a clinical service, and their value socially, were generally favourable (Table 9). Ninety-four percent of SARs supported having SNRs (Table 9), and the perceived negative impact of SNRs applied mainly to clinical and academic practice (Table 10).

Discussion

This is the first reported study to assess the SNR experience in the SA teaching hospital environment, and it highlights some positive aspects but also some concerns.

SA has a great deal to contribute in terms of improving healthcare in other African countries, of which training medical specialists is a core component. It is therefore pleasing to note that about 90% of SNRs planned to return to their home countries, and that the majority intended to work in the public sector.

Almost all SARs favoured having SNRs. This reflects the reliance that hospitals place on SNRs to provide clinical services in the face of staff shortages in our health system, in part owing to the shortage of paid positions for SARs.

Despite the positive educational experiences that the SNRs reported, their training comes at great personal and financial cost. While the SA public healthcare system is dependent on SNRs to provide a clinical service, they do not receive remuneration locally and many struggle to make ends meet. Our study highlights the need for universities to determine what constitutes a reasonable income for SNRs to live and train at their institutions and to advise prospective SNRs accordingly to avoid their falling into debt and dropping out of training programmes for financial reasons. It also highlights that there are great variations in income, and raises the importance of regular enquiry by the universities about the financial wellbeing of SNRs during their training.

The study raises other red flags that training programme directors need to heed. Many SNRs felt disadvantaged compared with their SA counterparts in terms of their learning opportunities and academic support, they also felt that they were disadvantaged in terms of call rosters, and about half reported xenophobia from SA colleagues.

Some SARs considered the academic and clinical contributions of SNRs to be of less value than those of SARs. While this may reflect the challenges many SNRs face early in their training because they come from different and sometimes inferior training programmes, all registrars ultimately pass the same exit examinations set by the Colleges of Medicine of South Africa to qualify as specialists.

Reported difficulties that prospective SNRs experience with registration with the HPCSA were not explored in this study; however, this process is known to be frustrating, tedious, timeconsuming and expensive.

Study limitations

Limitations of the study include a relatively low response rate, and absence of information on gender, race and country of origin. In addition, responses to the study were subjective given the questionnaire format.

Conclusions

SNRs provide an essential service to state hospitals despite not being remunerated. More can be done to improve the social and economic circumstances of SNRs, for which the beneficiaries of their enrolment collectively share a host responsibility.

Like SARs, SNRs are fee-paying postgraduate students and should enjoy the same academic and teaching support. The results of this study suggest that both the university and the teaching hospitals need to take steps to improve the integration of SNRs into the work environment, and to ensure that they have the same access as SARs to academic support and clinical teaching.

The university and the hospitals also need to take an interest in the financial wellbeing of SNRs by forewarning applicants about what it will cost for them to live, work and train in SA, and by including questions about financial and social wellbeing in their quarterly in-service assessments.

Of particular concern are perceptions of xenophobia from SA medical colleagues. This needs to be addressed by both the university and hospital authorities.

Recommendations

Training programmes, medical school postgraduate departments, government health structures and accreditation bodies should work together to initiate measures that will assist this marginalised and vulnerable group of doctors and improve the quality of their postgraduate training experience.

Registrar representative committees should include strategies that address SNR matters.

REFERENCES

1.Health Professions Council of South Africa. Registration. http://www.hpcsa.co.za/PBMedicalDental/Registration (accessed 9 July 2016). [ Links ]

2. Muula SA. Specialist training programs for African physicians. Croat Med J 2006;47(5):789-791. [ Links ]

3. World Health Organization. Transformative scale up of health professional education: An effort to increase the numbers of health professionals and to strengthen their impact on population. March 2011. http://www.who.int/hrh/resources/transformative_education/en/ (accessed 9 July 2016). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

S Peer

shazia.peer@uct.ac.za

Accepted 8 August 2016