Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.106 no.12 Pretoria dic. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2016.V106I12.10969

RESEARCH

Prevalence and correlates of violence among South African high school learners in uMgungundlovu District municipality, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

N KhuzwayoI; M TaylorII; C ConnollyIII

IMA Discipline of Public Health Medicine, School of Nursing and Public Health, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IIPhD Discipline of Public Health Medicine, School of Nursing and Public Health, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IIIMPH Discipline of Public Health Medicine, School of Nursing and Public Health, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. Young people grow up in homes and communities where many are exposed daily to crime and antisocial behaviours.

OBJECTIVE. To investigate the prevalence of violence and the demographic factors associated with such violence among South African (SA) high school learners in the uMgungundlovu District, KwaZulu-Natal, SA.

METHODS. In a cross-sectional study, we used stratified random sampling to select 16 schools in uMgungundlovu District. All Grade 10 high school learners (N=1 741) completed a self-administered questionnaire (Centers for Disease Control Youth Risk Behavior Survey). Data analysis was carried out using STATA 13 statistical software (Statacorp, USA).

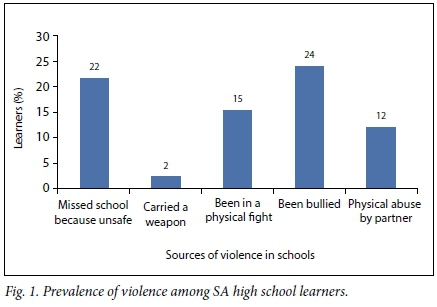

RESULTS. Of the participants in this study, 420 (23.9%) had been bullied, 379 (21.7%) had missed school because of feeling unsafe, 468 (15.4%) had been involved in physical fights and 41 (2.4%) had carried weapons to school. There was a significant association between being in a physical fight and missing school (odds ratio (OR) 2.5, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.9 - 3.3; p<0.001). There were higher odds of male learners carrying weapons than female learners (OR 5.9, 95% CI 2.0 - 15.0). Among learners living in rented rooms, the OR of feeling unsafe was 2.7 (95% CI 0.8 - 3.0), in an informal settlement the OR was 0.8 (95% CI 0.3 - 2.0) and in reconstruction and development programme houses it was 2.7 (95% CI 1.0 - 5.0), compared with learners residing in Zulu homesteads.

CONCLUSION. Violence among learners attending high schools in uMgungundlovu District is a major problem and has consequences for both their academic and social lives. Urgent interventions are required to reduce the rates of violence among high school learners.

Violence in South Africa (SA) is a social and public health concern.[1] The World Health Organization (WHO) defines violence as the intentional use of physical force or power, a threat or actual perpetration against oneself, another person or against a group or community that either results in, or has a high likelihood of resulting in, injury, death or psychological harm.[2] This includes bullying, physical fights and sexual assault.[2] For many years, young people in SA have been involved in political, criminal and gang-related violence.[3] There have been numerous research interventions as well as government and non-governmental efforts to prevent this; however, the rates continue to escalate.[4] Of the greatest concern is that young people are becoming perpetrators at a younger age.[3-5]

Young people can be harmed in significant and long-lasting ways from exposure to and perpetuation of violence, owing to their vulnerability at home, in school, in the community and in peer environ-ments.[4] Burton and Leoschut[3] report that many young people grow up in homes where they are exposed to intimate partner violence between caregivers and adult family members and abuse perpetrated against children. They further argue that some of these young people have been physically punished by their parents and others have witnessed people in their family intentionally attacking one another physically or using weapons.[3]

Young people spend much of their time at school and these schools exist within the broader context of the community. This population is thus affected by the activities, culture and norms of the community.[2,6] Primary social groups, such as family and friendship networks, affect a learner's social behaviour.[4] Hence, the social ills prevalent in communities are known to infuse the school environment.[3] A national survey on violence among learners from SA high schools studied 5 939 learners between August 2011 and August 2012. This survey reported that one in five learners (22.2%) had experienced some form of violence while at school, 12.2% of the learners had been threatened with violence, 6.3% had been physically assaulted, 4.7% had been sexually assaulted or raped and 4.5% had been robbed.[3] Females are at increased risk of violence as they are often dating men older than themselves.[5]

The consequences of violence among learners are well documented in the literature.[3,7] These include psychosocial problems, and poor academic performance and health outcomes.[8] Learners stay away from certain places in school or on the school grounds,[5] some stay away from school-related activities,[6] while others decide to stay out of school and remain at home.[3] Absence from school owing to fear of violence directly affects the psychological wellbeing and academic performance of learners.[5] Violence among young people is associated with depression, unwanted teenage pregnancy and HIV.[9] These consequences are not only linked to the victim but to all persons exposed to actions of violence.[9]

Young people are further exposed to other types of violence such as robbery, fights and sexual violence while commuting to and from school.[1-3] Violence in neighbourhoods and communities is precipitated by access to weapons such as guns and sharp objects.[3,5,6] The district of uMgungundlovu, where the study was conducted, is not a stranger to violence.[10] This district municipality comprises seven local municipalities: Impendle, Mkhambathini, Mpofana, Msunduzi, Richmond, uMngeni and uMshwathi. Since the late 1980s and 1990s, violence in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), SA has been characterised by complex power dynamics between political parties and factions. Violence has been prominent in black residential areas including townships, shack settlements and rural areas, including some of the uMgungundlovu rural areas.[10] This has been reported over the past decades and, although the levels of violence have decreased, violence continues to simmer.[11] Violence, especially protest violence and assassinations, still occurs in the uMgungundlovu District.[10] Understanding youth violence is critical for planning prevention programmes. Thus we investigated the prevalence of violence among uMgungundlovu District high school learners and the factors associated with such violence.

Methods

This was a quantitative cross-sectional study. Data came from 16 high schools in the uMgungundlovu District, KZN. The KZN Provincial Department of Education and district offices gave permission. Schools in each of the six local municipalities were randomly selected and a school's participation in the study was voluntary. There were no refusals. Meetings with principals were arranged to introduce the study, and to obtain their support and commitment. General information sessions with all the Grade 10 learners were conducted. Before data collection, information sheets about the study were sent home to parents/guardians providing information about the study. Thereafter, written consent for learners 18 years and older and assent for learners 17 years and younger were obtained.

The Centers for Diseases Control (CDC) Youth Risk Behaviour coded survey was self-administered by the learners in the classroom and this took about an hour. All Grade 10 learners in each of the 16 schools were invited to participate; there were 8 refusals and 20 absentees. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of KZN Biomedical Research Ethics Committee (ref. no.: BE342/14). Data analysis was carried out using STATA 13 statistical software (Statacorp, USA). Descriptive analyses were used for the sample characteristics. χ2 was used to determine associations between the levels of violence and key categorical demographic variables. Where statistical significance for variables in the bivariate analyses was p<0.2, multivariate analysis was undertaken and the adjusted OR reported. A statistical significance criterion of p<0.05 was adopted for all the analyses. A generalised estimating equation model was used to adjust for the possible correlation of students within schools.

Results

Demographic profile of participants

There were similar numbers of male and female participants, with males being older than females (p<0.001) (Table 1). The mean age of participants was 17 (standard deviation (SD) 2, range 13 - 23) years. More than a third of the learners (n=613, 35%) were residing with their mothers while only 464 (26%) were living with both parents. Overall, 1 512 (89%) of the participants lived in traditional Zulu homesteads which consist of a fenced yard with separate houses/traditional rondavels (round houses) built of blocks or wattle and daub. A few participants (n=35, 2%) reported living with employers who were sugar cane and/or livestock farmers. Over half (n=1 023, 61%) of the heads of the learners' household had been to high school but 40% of household heads were not working. Learners from municipality A comprised 21% of the sample, the highest number of any of the municipalities.

A graphical representation of prevalence of violence among SA high school learners is shown in Fig.1.

This will be discussed with reference to social and demographic factors associated with school violence (Table 2) and to the adjusted multivariate association between key demographic variables and school violence (Table 3).

Carried weapons in school during the past 30 days

Forty-one (2.4%) learners carried weapons to school. The odds of carrying weapons was higher in male learners (odds ratio (OR) 5.9, 95% confidence interval (CI) 2.0 - 15.0) than female learners (p<0.001). The odds of carrying weapons in the past 30 days among learners living in rented rooms was four times higher (OR 4.0, 95% CI 1.0 - 13.0), as was the odds for learners living in informal settlements (OR 9.4, 95% CI 3.0 - 32.0), compared with learners living in a Zulu homestead (p=0.006). Learners whose head of the household was employed as a skilled labourer (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.1 - 1.2), unskilled labourer (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1 - 0.8) or those who were not employed (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.3 - 1.4) were less likely to have taken a weapon to school in the previous month, compared with learners whose head of household was a professional (p=0.001).

Physical fights

Male learners 185 (21.2%) (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.0 - 2.0) were more likely to have been involved in physical fights than female learners (n=111, 12.6%; p<0.001). Physical fighting tended to increase with age. Learners aged 16 - 17 years reported more physical fights (17.6%, OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.0 - 2.0), while those aged 18 - 23 years (21.2%, OR 1.8, 95% CI 1.0 - 3.0; p<0.001) also reported more fights, compared with learners aged 13 - 15 years. Physical fighting was significantly more prevalent in schools located in municipality A (17.7%), B (25.2%) or C (18.9%) (p<0.001) compared with municipality D (13.0%), E (15.9%) or F (12.4%). The odds of learners reporting physical fighting in municipality B (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.0 - 2.0), municipality C (OR 0.1, 95% CI 0.7 - 2.6), municipality D (OR 0.7, 95% CI 0.4 - 1.0), municipality E (OR 0.8, 95% CI 0.5 - 1.0) or municipality F (OR 1.0, 95% CI 0.6 - 2.2.) differed significantly (p<0.001), compared with municipality A. There was a significant association between being in a physical fight and missing school (OR 2.5, 95% CI 1.9 - 3.3; p<0.001).

Safety

In terms of their feelings of security, 379 (21.7%) learners missed school at least once because of fears for their safety. The OR for feeling unsafe among learners living in rented rooms was 1.5 (95%

CI 0.8 - 3.0), in informal settlements was 0.8 (95% CI 0.3 - 2.0) and

in RDP houses was 2.7 (95% CI 1.0 - 5.0), compared with learners residing in a Zulu homestead. The OR of learners reporting feeling unsafe in municipality B was 1.6 (95% CI 1.1 - 3.0), municipality C 1.3 (95% CI 1.0 - 2.0), municipality D 0.6 (95% CI 0.3 - 0.9), municipality E 1.0 (95% CI 0.7 - 2.0) and municipality F 0.8 (95% CI 0.4 - 1.2), compared with municipality A.

Bullying

Nearly a quarter of learners (n=420, 23.9%) indicated that they had been bullied in the past 12 months. Learners who were bullied were significantly more likely to have missed school (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.3 - 2.2; p<0.001). The number of learners who reported being bullied through Facebook and WhatsApp instant messaging was 277 (15.8%). Although learners from municipality B (17.4%), C (17.1%) and E (17.5%) were more likely to be bullied on social media than learners from municipality A (14.4%), C (14.0%) and D (15.1%), this difference was not statistically significant.

Dating violence

The number of learners who reported being physically hurt by someone they were dating was 144 (12.1%, p=0.2). Learners from municipality B (17.9%) were more likely to report being hurt physically by someone they were dating (p=0.0003), while more learners from municipality C (11.5%) and D (11.5%) reported being forced to do sexual things such as touching and kissing unwillingly (p=0.0001), compared with other municipalities. Learners whose head of the household held a postgraduate qualification were more likely to report being physically hurt (21.7%, p=0.2) and forced to do sexual things, compared with learners whose head of household had only attended primary or high school.

Discussion

This study explored the relationship between violence and key demographic characteristics of learners attending public high schools in uMgungundlovu District. In the study, nearly a quarter of learners had been bullied in the past year, over 20% had missed school due to feeling unsafe, over 15% had been involved in physical fights

and 4.5% had been forced to have sex. Although male and female learners were both affected by violence, this study reports that male learners were more likely to carry weapons and therefore were more at risk of experiencing violence.[3-5] In the SA School Violence survey conducted by Burton et al.,[3] it was noted that female learners tend to report more acts of harassment, sexual assault and rape than male learners, and this can be attributed to the social construction of masculinity.[12] Girls and boys are not socialised in a similar manner in our societies.[13] For instance, boys are expected to be brave and not to show emotions such as crying, whereas girls are expected to be sensitive and kind.[14] Another explanation for this phenomenon of socialisation is that, generally, older male learners have a bigger physique than younger male and female learners.[3] In addition, male learners may grow up in homes and communities where older men display violent behaviour towards one another and even towards females.[4] Learners may then learn to model the behaviour of their parents and neighbours.[2]

Education is compulsory in SA and children start formal education at the minimum age of 6 years; however, many children start school at a later age and if they repeat a grade (or several grades), they will be older than others in the classroom. Some of these learners then start secondary education already older than 14 years, which is the entry age requirement.[15] The resultant wide age range was evident in this study and is a major and ongoing problem.[16] Research shows that the older learners are, the more they are likely to perpetrate delinquent behaviour such as substance abuse and violence, because these learners have spent more time in school than other learners, as some learners have repeated a grade.[5-6] In our survey, which targeted only Grade 10 learners, 30% of the learners were between the ages of 18 and 23 years, while only 46% were between 16 and 17 years, the expected grade age. This difference was significant.

Clearly, safety in SA schools is under threat,[5] given the high rates of crime in schools and in the communities where these schools are situated.[4] In this survey, 21.7% of learners had been absent from school for one or more days because of fear for their safety.[3,13] In the previous national survey on school violence, the rate of physical fights was 6.3%,[3] and in this study, physical fighting tended to increase with age, with learners aged between 18 and 23 years reporting more fights. These results are similar to the previous national survey.[3] In support of this finding, Ncontsa and Shumba[8] also found that older learners were responsible for initiating physical fights. Our study showed a significant association between being in a physical fight and missing school. Of concern is that learners who had been in a physical fight were 2.5 times more likely to miss school.[3,8]

Other forms of violence reported by the learners included dating violence and bullying. The results of our study mirror the results of previous research on adolescent/youth dating violence.[13] In this study, 8.3% of the learners reported being victimised by someone they were dating and over a quarter were forced to do sexual things (kissing and touching) by someone they were dating. Of concern in youth/adolescent dating are the consequences of such coercion, including unwanted pregnancy,[13] rape[14] and HIV,[13] especially for female learners, who are at particularly high risk as some are dating older men.[1]

There was also an association between missing school and bullying among the learners who indicated being bullied in the past 12 months. The negative actions included threatening, taunting, name-calling and teasing. Nearly a quarter of learners (23.9%) in this study reported being bullied and two-thirds of these said that they experienced such bullying on Facebook and WhatsApp. Cyber violence is part of a new and broader spectrum of bullying affecting SA.[3,6] The studies on bullying show that historically, physical bullying in schools has been in existence for decades.[3,4,8]

Although guidelines on bullying exist, most learners do not report it to school authorities.[15] Some of the reasons for reluctance to report included fear of being laughed at, being called 'mama's boy'[15] and that reporting such bullying will be followed by intensified actions of bullying.[5]

In this study, learners living in informal settlements and RDP houses were more likely to have carried weapons in the past 30 days. With increasing urbanisation in SA and the surge in the urban population, municipalities have been unable to meet housing needs and informal settlements have proliferated.[16] These settlements often provide inadequate housing and have a high unemployment rate that also affects social stability. Because of the severely underprivileged socioeconomic conditions of many of these learners, children from such families are often more violent than those from better-off families.[17] Historically, informal settlements have also been associated with high levels of crime.[18] In deep rural areas, however, there are few high schools and to avail themselves of the opportunity of a high school education, learners have to find places at high schools far from their homes and support structures.[16] For example, 44 (3%) learners in our study were residing in a rented room and another 43 (3%) in informal settlements.

Residing in a Zulu traditional homestead, living with a father or living with the extended family emerged as possible protective factors in this study. In SA, historical migrant labour practices separated fathers from their families.[17] We found that only a quarter of learners lived with both parents. Although there may be a number of factors contributing to this, the AIDS epidemic in the past two decades has resulted in the deaths of many adults of child-bearing age, leaving their children lacking adequate care.[19] Of interest is our finding that children of professionals were significantly more likely to have carried a weapon to school in the past 30 days. We are unsure as to what the reason might be. It may be that these learners have financial resources to purchase a weapon; however, the context of crime in SA has resulted in an increase in learners carrying weapons either for self-defence or to commit a crime.[19]

Study limitations

A cross-sectional design was used; therefore, it is impossible to determine the direction of the associations. The questionnaire relied on self reports and the prevalence rates are likely to be conservative estimates because learners may choose not to reveal instances of violence, despite the efforts taken to ensure privacy and confidentiality during data collection. Some questions were not sufficiently comprehensive for the topics investigated, e.g. for those on dating violence, forced sex and bullying, learners were not asked if they had perpetrated any of these forms of violence.

Conclusion

Although the findings of our study are not generalisable to the overall SA population of high school learners, they do indicate that violence is a significant problem for young people in KZN. Interventions aimed at preventing violence need to be increased and be aligned with the demographics of the area. Most of the schools in the study had learners who are much older than other learners in the classrooms, and the Department of Education and school governing bodies need to find ways of dealing with the mixed ages of learners, to reduce levels of violence in school. Safety in SA is a constitutional right.[18] Given the context of violence in SA high schools, some schools do not provide an environment conducive to learning.

More research is needed to understand why learners whose head of household is a professional are more likely to carry weapons than others and to investigate the prevalence and effects of cyberbullying through social media such as Facebook and WhatsApp.

Acknowledgement. We would like to thank the Provincial Department of Education, uMgungundlovu district office and the 16 high schools for allowing us to conduct the survey, and the Grade 10 learners for answering the questionnaires. The study was funded by the College of Health Sciences, University of KZN. The research was undertaken for the requirements of a Doctorate in Public Health.

References

1. World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Violence Prevention 2014. Geneva: WHO, 2014. (SA profile p. 195.) http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/corporate/Reports/UNDP-GVA-violence-2014.pdf (accessed March 2016). [ Links ]

2. Wilson HA, Hoge RD. Diverting our attention to what works: Evaluating the effectiveness of a youth diversion program. Youth Violence Juv Justice 2013;11(4):313-331. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1541204012473132 [ Links ]

3. Burton PA, Leoschut LE. School Violence in South Africa. Results of the 2012 National School Violence Study. Monograph series No.12. Cape Town: Centre for Justice and Crime Prevention, 2013. [ Links ]

4. Ward CL, Artz L, Berg J, et al. Violence, violence prevention, and safety: A research agenda for South Africa. S Afr Med J 2012;102(4):215-218. [ Links ]

5. Mncube V, Harber C. The dynamics of violence in South African schools. Report. Pretoria: University of South Africa, 2013. [ Links ]

6. Hutzell KL, Payne AA. The impact of bullying victimization on school avoidance. Youth Violence Juv Justice 2012;10(4):370-385. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1541204012438926 [ Links ]

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Understanding teen dating. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. Division of Violence Prevention. http://www.cdc/violenceprevention (accessed 16 March 2016). [ Links ]

8. Ncontsa VN, Shumba A. The nature, causes and effects of school violence in South African high schools. S Afr J Educ 2013;33(3):1-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.15700/201503070802 [ Links ]

9. Hamby S, Turner H. Measuring teen dating violence in males and females: Insights from the national survey of children's exposure to violence. Psychol Violence 2013;3(4):3233-3239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0029706 [ Links ]

10. Schuld M. The prevalence of violence in post-conflict societies: A case study of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Peacebuilding Dev 2013;8(1):60-73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15423166.2013.791521. [ Links ]

11. Taylor R. Justice denied: Political violence in KwaZulu-Natal after 1994. African Affairs 2002;101(405):473-508. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/afraf/101.405.473 [ Links ]

12. Banyard VL, Cross C. Consequences of teen dating violence: Understanding intervening variables in ecological context. Violence Against Women 2008;14(9):998-1013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1077801208322058 [ Links ]

13. Teten AL, Ball B, Valle LA, Noonan R, Rosenbluth B. Considerations for the definition, measurement, consequences, and prevention of dating violence victimization among adolescent girls. J Womens Health 2009;18(7):923-927. http://dx.doi.org/10.1089=jwh.2009.1515 [ Links ]

14. Exner-Cortens D, Eckenrode J, Rothman E. Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence, victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics 2013;131(1):71-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1029 [ Links ]

15. Langa M. Contested multiple voices of young masculinities amongst adolescent boys in Alexandra Township, South Africa. J Child Adolesc Ment Health 2010;22(1):1-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.2989/17280583.2010.493654 [ Links ]

16. Department of Basic Education. 2013 Progress Report: South Africa. Pretoria: Department of Basic Education, 2014. [ Links ]

17. Harrison P. The policies and politics of informal settlement in South Africa: A historical perspective. Africa Insight 1992;22(1):14-22. [ Links ]

18. Madhavan S, Townsend NW, Garey AI. 'Absent Breadwinners': Father-child connections and paternal support in rural South Africa. J S Afr Stud 2008;34(3):647-663. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03057070802259902 [ Links ]

19. Statistics South Africa. Annual Report 2014/15: Book 1. Pretoria: SSA, 2015. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Nelisiwe Khuzwayo

khuzwayone@ukzn.ac.za

Accepted 9 September 2016.