Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.106 n.12 Pretoria Dec. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2016.V106I12.12128

CME

Using a child rights approach to strengthen prevention of violence against children

L LakeI; L JamiesonII

IBA Hons; Children's Institute, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIBA Hons, MSocSci; Children's Institute, Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Violence against children is widespread in South Africa. Much of it remains hidden, and social services are thinly stretched. This article therefore focuses on children's rights to protection and considers the implications for healthcare practice. Children's rights can be considered both a 'language of critique' and a 'language of possibility' - encouraging us to evaluate current practice from a child-centred perspective and to re-imagine ways in which we deliver healthcare services. The article outlines the nature, extent and long-term effects of violence against children, introduces a framework for conceptualising violence prevention, and considers ways in which health professionals can better respond to cases of abuse and neglect, and prevent violence against children from taking place.

In March 2015, media attention focused on the rape and murder of two Cape Town teenagers - Franziska Blochliger, who was attacked while running in the Tokai forest, and Sinoxolo Mafevuka, who was strangled to death in Khayelitsha. Their stories are brutal, tragic and shocking, but these are not isolated events. Violence against women and children is pervasive in South Africa (SA), cutting across class and race divides. Of the >62 000 sexual offences reported in 2013/14, one in every three victims was <18 years of age.[1]

The abovementioned high-profile cases suggest that most instances of violence against children are committed by strangers. Yet, the findings of the 2009 child homicide study tell a different story:

• Adolescent boys are five times more likely to be murdered than teenage girls, and most are killed by acquaintances in the context of interpersonal violence.

• Nearly half (45%) of child homicides occurred in the context of child abuse and neglect; of these 36% were babies abandoned in the first week of life, and 74% were under 5 years of age. Most occurred in the home and the perpetrator (most often the mother) was known to the child.[2]

What kinds of violence do children experience in SA?

While homicide is the most extreme form of violence against children, community-based studies suggest that at least 55% of children have been physically abused by caregivers, teachers or relatives;[3] 35 -45% have witnessed domestic violence;[4] and corporal punishment remains widespread, with nearly 58% of parents using physical punishment and 33% using a belt or stick.[5]

A 2016 national prevalence study found that 1 in 3 children has been sexually abused.[6] Boys and girls are equally vulnerable, with girls more likely to experience forced and penetrative sex, and boys more likely to be exposed to sexual acts and pornographic material. Nearly a third were abused by a known adult. Only 33% sought assistance for their injuries - with boys least likely to tell anyone about sexual abuse.

Most violence against children remains hidden and unreported, and it mostly occurs in the home, where children are relatively powerless and dependent on adult support. Corporal punishment and intimate partner violence are widely tolerated, and in cases of sexual abuse, children are often groomed and/or threatened by the perpetrator. The family may blame the child and side with the perpetrator. Unsurprisingly, children often choose to remain silent, as they fear intimidation and not being taken seriously[6]

How does this change across the life course?

Violence starts in the home where young children are most at risk of physical abuse, neglect and abandonment. At school, corporal punishment, bullying and sexual violence become more prevalent. Teenage boys are most at risk of interpersonal violence, while teenage girls are more likely to experience sexual and physical violence in the context of dating relationships;[7] >33% of teenage girls report forced sexual initiation.[8] Understanding how patterns of violence change across the life course enables the adoption of a proactive approach to violence prevention - intervening early before patterns of violence become entrenched (Fig. 1).

What are the effects of violence on children?

The impact of violence extends beyond physical injury and has a cumulative and long-lasting effect on children's cognitive and psychosocial development, including impaired attachment, failure to thrive, trauma, anxiety and depression, and aggressive, antisocial or self-destructive behaviour.[9]

The cycle of violence is rooted in early childhood, where exposure to strong, frequent or long-lasting physical or emotional abuse, domestic violence, neglect, caregiver substance abuse, and mental illness results in 'toxic stress', causing neurological and psychological damage with long-term consequences for learning, behaviour, and physical and mental health.[10]

Girls tend to internalise their experiences of violence, exhibiting signs of depression, anxiety and suicidality, while boys tend to externalise through risk-taking and aggressive behaviour. Exposure to violence increases the risk of re-victimisation or perpetration later in life: girls are at increased risk of sexual assault and intimate partner violence, while boys are more likely to become perpetrators.[11, 12] The effects of violence extend into adulthood, where limited emotional control, substance abuse and violence may compromise relationships and parenting abilities.[12-14] It is therefore essential to intervene as early as possible to break the intergenerational cycle of violence.

How do we break the cycle of violence?

Efforts have traditionally focused on responding to incidents of violence, yet it is more effective - and less costly - to prevent children from getting hurt.[15, 16] Prevention can occur before and after violence:

• Primary prevention aims to prevent violence before it takes place (e.g. by building self-esteem and promoting positive forms of discipline).

• Secondary prevention focuses on immediate responses to violence (e.g. ensuring the safety of the child and providing medical care).

• Tertiary prevention includes short- and long-term interventions to reduce trauma and rehabilitate both child victims and offenders.

In SA, the Children's Act No. 38 of 2005[17] makes a similar, but different, distinction between prevention, early intervention, and child protection services, where:

• Prevention focuses on strengthening the capacity of families to safeguard children's wellbeing and best interests by promoting healthy non-violent relationships and assisting families to access essential services.

• Early intervention offers targeted support to families at risk and includes therapeutic programmes, family preservation programmes and temporary safe care.

• Child protection services investigate reports of child abuse and neglect, provide counselling and therapeutic services, and may place the child in temporary safe care.

Yet, social work services in SA are under-resourced and overstretched, and budgets are focused on child protection rather than prevention and early intervention services.[18] A more proactive approach is needed, increasing investment in prevention services and exploring ways other sectors can strengthen and support children and families.

Identifying risk and protective factors

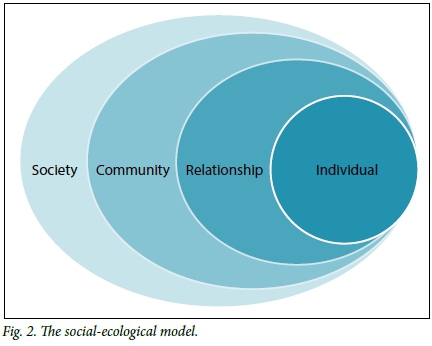

The causes of violence are complex and the chances of a child becoming either a victim or perpetrator are shaped by their personal history, close relationships, communities and broader society. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's social-ecological model (Fig. 2) provides a useful framework, encouraging recognition of the complex interplay of risk and protective factors (Table 1) to inform prevention efforts.[19]

Adopting a rights-based approach

Children's rights to protection are enshrined in the SA Constitution, African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, and United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child. Section 12 of the Bill of Rights states that everyone has the right to be 'free from all forms of violence' and 'not to be treated or punished in a cruel, inhuman or degrading way', while Section 28 recognises 'the right of every child to be protected from maltreatment, neglect, abuse or degradation'. [20]However, what does this mean in practice?

The UN Committee on the Rights of the Child[21] issues general comments that provide guidance on how to interpret and give effect to children's rights and evaluate progress. General Comment 13 focuses on the child's right to freedom from violence and outlines key principles that should guide our approach to violence prevention.

General Comment 13 highlights ways in which violence threatens children's survival, health, development, and dignity. It also acknowledges how children's access to social assistance, family and alternative care, education, healthcare and social services can be protective. Children's rights are thus interdependent and indivisible. The General Comment calls for an holistic and co-ordinated approach to address multiple risk factors across a range of settings and to 'overcome isolated, fragmented and reactive approaches to violence prevention'.[21] In particular, it calls for a paradigm shift in child care and protection that recognises children's human dignity, individual personalities, distinct needs and interests. It recognises children's agency and evolving capacities, and argues that 'their empowerment and participation should be central to child caregiving and protection strategies and programmes'.[21] This is particularly pressing in the SA context, where children are often silenced and socialised to respect and obey adults without question, making them more vulnerable to abuse and exploitation, and reluctant to report abuse.

What are the implications for health care practice?

Health professionals have a vital role to play in violence prevention. Critical opportunities exist to support children and families across the life course, from early childhood to adolescence.

Enable children's participation

Children have a right to participate, and ensuring that they can express their views and are heard and taken seriously, assists with violence prevention.

What can I do?

• Make children feel welcome.

• Build trust (by respecting children's rights to privacy, confidentiality and physical integrity).

• Provide information in a language and format that is child and youth friendly.

• Encourage children to speak out and ask questions.

• Listen carefully to their words and body language, and to what is said and left unspoken.

• Take children seriously and recognise and respond to early warning signs.

• Treat what they say with confidence, subject to statutory reporting obligations.

• Ask, and receive permission, before touching.

In other words, we need to build relationships of trust, facilitate open communication, take children seriously, and give them the confidence to speak out rather than enact blind obedience to adults in authority[22]

Support caregivers of young children in the first 1 000 days

Early intervention can potentially break the cycle of violence. Sensitive and responsive caregiving has been found to prevent or reverse the damaging effects of toxic stress, helping children regulate their behaviour and emotions, and providing a solid foundation for future relationships and schooling. Furthermore, it is important to: reduce children's exposure to abuse, conflict and violence; address caregivers' mental illness, including substance abuse; and alleviate extreme poverty[23]

The new National Integrated Policy on Early Childhood Development recognises the central role of caregivers and their need for support, especially in the first 1 000 days of life (from conception until the child's 2nd birthday).[24] It also recognises how health services are often the primary if not the only point of contact with young children and families, and can serve as a critical gateway to other forms of support, such as social grants and social services.

What can I do?

Before the child is born:

• Be supportive, not judgemental.

• Screen for maternal mental health, substance abuse, domestic violence. Help women access support services.

• Many pregnant women feel isolated and overwhelmed; therefore, encourage them to get the support they need from partners, friends and family.[25]

After the child is born:

• Take time to ask how mothers are doing, as their wellbeing is central to that of the child.

• Observe mother-to-child interactions and promote warm responsive caregiving.

• Look out for and respond to signs of maternal depression, domestic violence and harsh parenting.

• Encourage the active involvement of fathers in maternal and child health and child care.

• Support the call for a ban of corporal punishment. Enquire about positive discipline and share these techniques with your patients.[26]

• Find out about social grants, child maintenance, training and income-generating programmes so that you know how to help families in need of financial support.

Promote adolescent health and youth development

Adolescence is a period during which lifelong behaviour patterns are established. As a time of increased risk behaviour, it offers opportunities for support and intervention. Yet, adolescents complain of being treated with a lack of respect, privacy and confidentiality that compromises their access to healthcare services.[27, 28]

loveLife has spearheaded the development of adolescent- and youth-friendly clinics that aim to respond to these challenges. They have also extended their work beyond healthcare facilities, through their groundBREAKERs youth development programme that reaches out from their Y-centres to promote healthy lifestyles, while two toll-free helplines provide information, guidance and counselling in a safe and non-judgemental environment.[29]

Moreover, it is important to work with parents as the UBS Optimus study found that parents' knowledge of 'who young people spend their time with, and how they spend their time and where they go' can prevent child maltreatment, as do warm and supportive parent-child relationships.[6]

What can I do?

• Contact loveLife to find out how to develop a youth-friendly service.

• Provide information about healthy relationships and local youth development programmes.

• Encourage parents to remain involved and supportive.

• Find out about programmes run by Sonke Gender Justice that work with boys and men to promote gender equality and prevent gender-based violence.

Identify other potentially vulnerable children

• Actively consider the wellbeing of children in contexts of domestic violence or substance abuse. Put systems in place to ensure their safety and protection.

• Recognise that children with disabilities are particularly vulnerable to neglect and physical and sexual abuse in the home, community and institutional settings. Promote inclusion, address stigma and provide respite care and support for caregivers.[30]

• Put plans in place to safeguard children when their primary caregiver is hospitalised, and ensure that your facility has a child protection policy to ensure the safety of child patients and provide clear guidelines for the reporting of child abuse.[6]

Respond to abuse and neglect

The Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act (32 of 2007) makes reporting sexual offences mandatory for anyone who has 'knowledge' of a sexual offence committed against a child. This includes consensual sexual activities between a child <16 years of age and anyone >16 years old, where their age gap is >2 years (in 2015, the definitions of consensual sexual activities in the Sexual Offences Act were amended, which changed the nature of the offences of statutory rape and statutory sexual assault).[31] Particular care should be taken when reporting children for consensual sexual activities, as it may violate their rights and best interest.[32] Any child younger than 12 is considered too young to consent to sex, therefore any sexual act with a young child constitutes rape (if there is penetration) or sexual assault.

In addition, the Children's Act[17] obliges certain professionals to report if they conclude on reasonable grounds' that a child has been abused in a manner causing physical injury; sexually abused; or deliberately neglected; where their conclusion is based on the balance of probabilities following observation of signs and indicators.

The reason for mandatory reporting is based on the assumption that children are relatively vulnerable and powerless in society and less able to protect themselves. Persons such as health professionals, teachers, psychologists and social workers carry a higher duty of care owing to their professional ethical responsibilities and heightened positions of authority and credibility in society. If you report in good faith, but it turns out that the signs you observed were not the result of abuse, you cannot be prosecuted or sued in a civil court. However, if you do not report, you can be held accountable and face suspension by the Health Professions Council of SA, or be fined or imprisoned. [33]

Both laws aim to protect the affected child and others from harm. However, the Children's Act aims to link children and families with support services, while the objective of the Sexual Offences Act is to prosecute perpetrators. [17,32]

What must you do?

• Make sure you are familiar with the signs of physical, emotional and sexual abuse and neglect as outlined in Regulation 35 of the Children's Act.[17]

• Learn how to manage disclosure. (Remain calm, listen, empathise and affirm. Reassure the child that they are not to blame: Ί believe you. It's not your fault.' Support and safeguard the child and minimise secondary trauma.)

• Know how to report abuse and neglect and to complete Form 22 to initiate a social work investigation.[34]

• Make sure abused children are prioritised and receive immediate medical attention, including mental healthcare, to minimise secondary trauma.[6]

• Recognise that disclosure and reporting cause significant distress for the child and family and can disrupt the home environment. Therefore, follow up to ensure children have received counselling and therapeutic support.

Strengthen safety nets and care pathways

Given the complex interplay of risk and protective factors, it is vital to engage with a range of service providers to strengthen safety nets and care pathways. The Thuthuzela Care Centres (TCCs) provide one model of best practice, bringing together specialised health professionals, police investigators, prosecutors and social workers to provide an integrated service for sexual and intimate partner violence. Located in public hospitals, the TCCs aim to reduce secondary trauma and improve conviction rates by providing counselling, medical care, and more efficient and sensitive police investigations.

What can I do?

• Build a directory of local services. Find out about the child protection organisations in your district.[35] Get to know them personally to facilitate referrals and follow-up.

• Make information about confidential helplines and local support services available in wards and waiting areas so that children, youth and caregivers are able access these services independently.

• Think beyond child protection. Build a broader network of organisations that promotes the health, safety and wellbeing of children, families and communities - from parenting programmes, moms and tots groups and early childhood development centres to sports and cultural programmes that promote the health, safety and wellbeing of children, families and communities (Table 2).

Conclusion

Healthcare providers are ideally placed to protect children from violence, and have both a legal and moral obligation to respond to cases of abuse and neglect, and to prevent violence against children from taking place. A child rights approach foregrounds the benefits of child participation and intersectoral collaboration in promoting safe and healthy homes, communities and relationships. In addition, it requires health professionals to view children with fresh eyes, to listen and take them seriously, and to speak out against violence in all its forms.

Acknowledgements. This article draws on the findings of the South African Child Gauge 2014[7]and focuses on preventing violence against children and the implications for healthcare practice. It also draws on lessons learned from engaging with health and social service professionals and identifying opportunities for systems strengthening through the Children's Institute's courses on child rights and child law

References

1. South African Police Service. Police Crime Statistics. Pretoria. SAPS, 2014. [ Links ]

2. Mathews S, Abrahams N, Jewkes R, Martin LJ, Lombard C. The epidemiology of child homicides in South Africa. Bull World Health Organ 2013,-91(8).562-568. http://dx.doi.org.10.2471/BLT.12.117036 [ Links ]

3. Meinck F, Cluver LD, Boyes ME, Loenig-Voysey H. Physical, emotional and sexual abuse of children in South Africa. Prevalence, incidence, perpetrators and locations of child abuse victimisation in a large community sample. J Epidemiol Community Health 2016,70(9).910-916. http://dx.doi.org.10.1136/jech-2015-205860 [ Links ]

4. Nagia-Luddy F, Mathews S. Service Responses to the Co-victimisation of Mother and Child. Missed Opportunities in the Prevention of Domestic Violence. Technical Report. Cape Town: Resources Aimed at the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect and Medical Research Council, 2011. [ Links ]

5. Dawes A, Kafaar Z, Richter L, Kropiwnicki Z. Survey examines South Africa's attitude towards corporal punishment. HSRC Institutional Repository 2005,1(2).2-4. [ Links ]

6. Artz L, Burton P, Ward CL, et ai. Optimus Study South Africa. Technical Report. Sexual Victimisation of Children in South Africa. Final Report of the Optimus Foundation Study. South Africa. Zurich* UBS Optimus Foundation, 2016. [ Links ]

7. Mathews S, Benvenuti P. Violence against children in South Africa. Developing a prevention agenda. In. Mathews S, Jamieson L, Lake L, Smith C, eds. South African Child Gauge 2014. Cape Town. Children's Institute, University of Cape Town, 2014. [ Links ]

8. Mahlangu P, Gevers A, de Lannoy A. Adolescents. Preventing interpersonal and gender-based violence. In. Mathews S, Jamieson L, Lake L, Smith C, eds. South African Child Gauge 2014. Cape Town. Children's Institute, University of Cape Town, 2014. [ Links ]

9. Pinheiro PS. World Report on Violence Against Children. Geneva. United Nations, 2006.63-66. [ Links ]

10. Center on the Developing Child. The impact of early adversity on child development. 2007. http://www.developingchild.harvard.edu (accessed 14 October 2016). [ Links ]

11. Dunkle K, Jewkes R, Brown HC, et al. Prevalence and patterns of gender-based violence and revictimization among women attending antenatal clinics in Soweto, South Africa. Am J Epidemiol 2004,160(3).230-239. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwhl94 [ Links ]

12. Mathews S, Jewkes R, Abrahams N. "I had a hard life'". Exploring childhood adversity in the shaping of masculinities among men who killed an intimate partner in South Africa. Br J Criminol 2011,51(6).960-977. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azr051 [ Links ]

13. Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. The relationship of adult health status to childhood abuse and household dysfunction. Am J Prev Med 1998-,14:245-258. [ Links ]

14. Gershoff E. Spanking and child development. We know enough now to stop hitting our children. Child Develop Perspect 2013-,7(3)-.133-137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cdep.l2038 [ Links ]

15. Fang X, Brown DS, Florence CS, Mercy JA. The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United States and implications for prevention. Child Abuse Neglect 2012,36(2).156-165. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.10.006 [ Links ]

16. Doyle O, Harmon CP, Heckman JJ, Tremblay RE. Investing in early human development. Timing and economic efficiency. Economics Human Biol 2009;7:1-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2009.01.002 [ Links ]

17. South Africa. Children's Act No. 38 of 2005. [ Links ]

18. Jamieson L, Wakefield L, Briede M. Towards effective child protection. Ensuring adequate financial and human resources. In. Mathews S, Jamieson L, Lake L, Smith C, eds. South African Child Gauge 2014. Cape Town. Children's Institute, University of Cape Town, 2014. [ Links ]

19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The Social-Ecological Model. A Framework for Prevention. 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/overview/social-ecol ogicalmodel.html (accessed 16 October 2016). [ Links ]

20. Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. Pretoria. Government Printer, 1996. [ Links ]

21. United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child. General Comment No. 13. The right of the child to freedom from all forms of violence. Geneva. UN, 2011. [ Links ]

22. Kruger J, Coetzee M. Children's relationships with professionals. In. Jamieson L, Bray R, Viviers A, Lake L, Pendlebury S, Smith C, eds. South African Child Gauge 2010/2011. Cape Town. Children's Institute, University of Cape Town, 2011. [ Links ]

23. Tomlinson M. Caring for the caregiver. A framework for support. In. Mathews S, Jamieson L, Lake L, Smith C, eds. South African Child Gauge 2014. Cape Town. Children's Institute, University of Cape Town, 2014. [ Links ]

24. Republic of South Africa. National Integrated Early Childhood Development Policy. Pretoria. Government Printer, 2015. [ Links ]

25. Field S, Honikman S, Woods D. Bettercare - maternal mental health. A guide for health and social workers. Perinatal Mental Health Project, http://pmhp.za.org/ (accessed 27 October 2016). [ Links ]

26. Save the Children's Resource Centre. Alternatives to corporal punishment, http://resourcecentre.savethechildren.se/keyword/positive-discipline (accessed 27 October 2016). [ Links ]

27. World Health Organization. Health for the world's adolescents - a second chance in the second decade. 2015. http://apps.who.int/adoles cent/second-de cade/section 6/page3/quality-&-coverage.html (accessed 16 October 2016). [ Links ]

28. Geary RS, Gomez-Olive FX, Kahn Κ, Tollman S, Norris SA. Barriers to and facilitators of the provision of a youth-friendly health services programme in rural South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res 2014,14.259. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-259 [ Links ]

29. loveLife. www.lovelife.org.za (accessed 27 October 2016). [ Links ]

30. Groce NE. Violence against disabled children. UN Secretary General's Report on Violence against Children Thematic Group on Violence against Disabled Children. Findings and Recommendations. New York. UNICEF, 2005. [ Links ]

31. Bhamjee S, Essack Z, Strode A. Amendments to the Sexual Offences Act dealing with consensual underage sex: Implications for doctors and researchers. S Afr Med J 2016,106(3).256-259.1 http://dx.doi.org.10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i3.9877 [ Links ]

32. McQuoid-Mason D. Mandatory reporting of sexual abuse under the Sexual Offences Act and the 'best interests of the child'. S Afr J Bioethics Law 2011,4(2):74-78. [ Links ]

33. Hendricks ML. Mandatory reporting of child abuse in South Africa. Legislation explored. S Afr Med J 2014,104(8).550-552. http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.8110 [ Links ]

34. Jamieson L, Lake L. A Guide to the Children's Act for Health Professionals. 5th ed. Cape Town. Children's Institute, University of Cape Town, 2013. [ Links ]

35. Department of Social Development. Children Services Directory. http://csd.dsd.gov.za/ (accessed 27 October 2016). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

L Lake

lori.lake@uct.ac.za