Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.106 n.12 Pretoria Dec. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2016.VL06IL2.12129

CME

Maternal mental health and the first 1 000 days

R E TurnerI; S HonikmanII

IMSc, Postgraduate Diploma in Montoring and Evaluation; Perinatal Mental Health Project, Alan J Flisher Centre for Public Mental Health, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIMB ChB, MPhil . Perinatal Mental Health Project, Alan J Flisher Centre for Public Mental Health, Department of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Even though maternal mental health receives low priority in healthcare, it is a vital component for the developing fetus and the raising of healthy children who are able to contribute meaningfully to society. This article explores risk factors for common mental illnesses and treatment options available in under-resourced settings.

The first 1 000 days of a child's life have been identified as a period of substantial vulnerability, which also carries the potential for lifelong health, prevention of disease and intellectual development. These 1 000 days, which start at conception and continue to the end of the child's 2nd year, have become the target area for many public health interventions that focus on nutrition, early childhood development and maternal physical health and mental wellbeing.

Common mental disorders (CMDs) include depression and the anxiety disorders. Some scholars and practitioners also include alcohol and substance use disorders in this group. The CMDs are distinguished from psychotic disorders, because in CMDs there is no loss of contact with reality, and there are no delusions or hallucinations. CMDs affect thoughts, feelings and behaviours over a period of time and have an associated effect on functioning in the home, relationships, community, work or school. Living with a CMD is debilitating for those who are affected.

In South Africa (SA), where there is limited focus on mental health, an estimated 20 - 25% of those in need of help have access to adequate treatment and healthcare for their mental health needs.[1,2] This treatment gap between those in need and those who receive treatment relates to shortages of mental health workers, lack of public awareness about possibilities for improvement and recovery, and stigma and discrimination against people suffering from mental health problems. This prevents individuals from seeking help, even where services are available and accessible.[3]

CMDs during the first 1 000 days of a child's life are of particular concern because of the disabling effects on the mother's ability to function, and the possible negative physical and developmental effects on the fetus and infant.[4]

Risk factors for poor maternal mental health

A previous history of mental illness is one of the strongest risk factors for CMDs during pregnancy[5] In SA, where there is a large treatment gap, this risk is usually unknown. Other factors that increase the likelihood of women developing a CMD during and after pregnancy are social rather than biological, and these are exacerbated by poverty. Lack of social support, including emotional and financial support from partner, friends or community, intimate partner violence, an unintended or unwanted pregnancy, low levels of education, adolescent pregnancy, and alcohol and substance use comprise key risk factors.[6] Women living in poverty may encounter food insecurity, which carries other risks for the developing fetus. These and other risk factors are highlighted below.

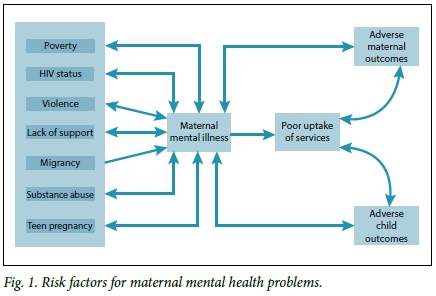

Maternal mental disorders often result in lower uptake of available services by mothers. This is a result of several factors, including a compromised ability to plan effectively, together with low levels of energy and motivation and fear of discrimination. Decreased access to care, in turn, leads to adverse maternal and child outcomes, which further add to levels of stress and consequently increase mental health problems. Similar vicious cycles of escalation exist between many risk factors and mental health problems, as can be seen in Fig. 1.

Poverty

It is important for SA healthcare workers to be aware of the poverty-mental illness cycle documented in low- and middle-income countries.[1] There is an increased risk of mental illness for those living in poverty, and an increased likelihood that those suffering from a mental illness will drift into or remain in poverty. The driving forces for this cycle are complex and include factors such as additional stresses of unemployment, poor housing and food insecurity. Furthermore, women living in poverty are more likely to have low educational levels and thus are unlikely to be able to generate adequate income, if they do find work. Women with CMDs are also more likely to experience stigma and social isolation and are prone to develop physical conditions and symptoms. Therefore, in addition to being more likely to spend time away from work, thereby losing income-generating potential, it is more probable that they will spend time and money on healthcare.[2]

HIV status

Many women learn about their HIV status during pregnancy. A positive result can have a significant impact on a woman's mental health. In SA, the prevalence of any diagnosable mental disorder among people living with HIV/AIDS is 43.7%, which is significantly higher than the rate of 30.3% in the general population.[7,8] Depression is associated with lowered adherence to antiretroviral medication and poor use of antenatal care and prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) programmes.[9] Mental illness is a significant factor in AIDS-related mortality among women.[10] Local research has shown that HIV-positive women are more likely to experience abuse, and those who are abused, are more probable to contract HIV.[11]

Violence

SA has one of the highest rates of gender-based violence in the world. In addition, local research has shown that abuse and violence tend to increase during pregnancy, with the severity increasing as the pregnancy progresses. Abuse during pregnancy contributes to pregnancy complications and miscarriages.[11] The mental health sequelae of gender-based violence include substance misuse and CMDs, such as post-traumatic stress disorder, depression and suici-dality. In addition to violence resulting in CMDs, those with mental health problems are also more vulnerable to experiencing domestic and gender-based violence.

Adolescents

Pregnant teenagers experience higher rates of depression than pregnant adults.[12] Teenage mothers with untreated depression have a far greater likelihood of having a second pregnancy within 2 years.[13] Mental disorders in teenagers are more likely to persist throughout adulthood. Maternal mortality data in SA show high rates of suicide in women <20 years of age and during their first pregnancy. Teenage mothers with a CMD are also less likely to complete their education, and more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviour. Teenage mothers are less likely to attend prenatal care, which increases the pregnancy risk in this age group. Also, there is a greater risk of pre-eclampsia and risks associated with a small bony pelvis.[14,15] Another factor that impacts on their children is that teens are likely to develop harsh parenting styles, which are associated with an increased risk for child mental health disorders.[16,17]

Refugees and migrants

CMDs are more prevalent in refugee women, who frequently experience extreme trauma, violence, rape and loss of loved ones when they flee from their countries. In cases of language differences, and a mistrust of others developed through the experience of war and oppression, refugee women may find it difficult to make friends and they have little support - all strong risk factors for developing CMDs.[18]

Mental ill-health in the perinatal period

It is important to note that baby blues, which commonly occurs in the early postnatal phase, is not a mental health disorder. Postnatal psychosis, which occurs in 0.02% of births, is not a CMD, but a psychotic disorder.

Baby blues

Baby blues is not a common mental disorder but rather a temporary psychological state occurring in 50 - 80% of mothers. It usually starts on the 3rd day after delivery and is linked to hormonal changes. It involves sudden mood swings (feeling very happy, then very sad), crying for no apparent reason, and feeling impatient, unusually irritable, restless, anxious, overwhelmed, inadequate, lonely and sad. These symptoms last from a few hours to 2 weeks after delivery, and usually resolve with compassionate support. About one-fifth of women with baby blues go on to develop depression.

Depression

Depression or a major depressive episode is characterised by low mood, loss of interest and enjoyment, and reduced energy for at least 2-4 weeks.

Common symptoms of depression also include:

• extreme sadness, tearfulness

• difficulty in concentrating, forgetfulness

• disturbed appetite or sleep (too much or too little)

• thoughts of worthlessness (low self-esteem)

• feelings of guilt

• helplessness, hopelessness

• irritability

• extreme tiredness

• loss of sex drive

• many physical symptoms, such as body aches and pains

• ideas or attempts of self-harm or suicide.

Anxiety

Anxiety is characterised by an abnormal and great sense of uneasiness, worry or fear. The symptoms of anxiety are normal in the presence of a real threat. However, when someone suffers from these symptoms in response to ordinary events, and the symptoms interfere with daily tasks, then they may have an anxiety disorder.

Symptoms of anxiety include emotional symptoms, such as:

• nervousness

• worry

• panic

• irritability

• feelings of dread

• tiredness

• fear of being alone or with others

• difficulty concentrating.

Anxiety also results in physical symptoms, which include:

• sleep disturbance

• physical tension

• sweating

• increased pulse

• muscle tightness

• body aches or gastrointestinal problems (e.g. nausea, diarrhoea).

A careful history may be required to distinguish the typical physical symptoms of pregnancy from those of anxiety. Furthermore, it is important to note that depression and anxiety often coexist and that there is substantial overlap of symptoms.

Postpartum psychosis

In contrast to the conditions described above, postpartum psychosis is a psychotic disorder - a severe mental condition that results in abnormal thinking and perceptions. People with psychoses are out of touch with reality. Two of the main symptoms of psychosis are delusions and hallucinations. The management of psychosis depends on the type of disorder and is fortunately relatively rare. However, in the postnatal period, the development of psychotic symptoms may be more rapid than at other times and there are greater associated risks of harm. Therefore, referral to specialist mental healthcare is urgent in these cases. Postnatal psychosis occurs in 2:1 000 births, but women with a history of bipolar disorder are at a greatly increased risk.

Poor maternal mental health

Poor maternal mental health may have a profound and wide-reaching effect on mothers, pregnancy and children.

Effect on the neonate and pregnancy outcomes

Untreated maternal anxiety may cause hormonal alterations in the intrauterine environment that have persistent implications for the physical, cognitive and emotional development of the child.

The following occur in pregnant women with common mental disorders:

• a higher incidence of miscarriage

• a higher risk of bleeding during pregnancy

• higher rates of caesarean section delivery

• higher rates of preterm delivery

• prolonged labour

• low-birth-weight babies (a primary cause of infant mortality and morbidity).

Effect on the child

Mothers with a CMD are more likely to have impaired bonding with their infants, which may result in breastfeeding problems. These mothers are more probable to discontinue breastfeeding early.

The emotional and psychological development of the child may also be significantly impacted when the mother has mental health problems. Children have a higher risk of developing the following:

• conduct problems

• attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

• anxiety symptoms

• child antisocial personality traits.

Research shows that later in life, children of depressed mothers are also more likely to be abused, to perform poorly at school and to develop mental illness. Fathers and others who provide maternal support play an important buffering role in reducing the effects of CMDs on children. It should, however, be remembered that fathers may develop paternal depression, which is also associated with adverse child outcomes.

Effect on mothers

With regard to the wellbeing of the mother, studies show that CMDs result in the following:

• an increased likelihood of mothers 'self-medicating' with alcohol or drugs

• reduced sleep and appetite

• poor antenatal weight gain

• increased probability of maternal mortality.

Studies in developed countries have shown that suicide is a leading cause of maternal mortality, with higher rates of suicide in women <20 years old and in their first pregnancy. In addition, if left undiagnosed and untreated, mental illness can increase a woman's risk of HIV infection, violence and abuse, economic insecurity, and subsequent unintended pregnancy.

Management of CMDs

Management of CMDs should be based on the following principles:

• detection

• empathic care

• psycho-education

• early treatment

• holistic management

• suicide risk assessment.

Detection

Ideally, every woman should be screened several times during pregnancy and in the first years postpartum, when she engages with health or social services. As this is not always possible, care should be taken to screen women at least once during and after pregnancy. A combination of risk factor screening and symptom screening is recommended. Attempts are being made to include screening questions into standardised stationery.

There are several screening tools available for common mental problems. The most commonly used tools are:

• The Whooley depression screen (two yes/no items plus an item on whether help is desired).[19]

• The Edinburgh postnatal depression scale (EPDS) (10 multiple-choice items).[20]

These tools have been validated for use in the SA setting. It is important to note that these screening tools are not diagnostic. Further assessment by a qualified practitioner may be required for a diagnosis.

Empathic care

Empathic care should form the basis for all communication with all women during the perinatal period. It includes creating a safe, caring space, active listening to understand her problems, and empowering the mother by assisting her to find her own solutions. Not every woman needs to be referred for specialist care. Many respond positively to empathic care provided by general health workers. Women may be offered practical strategies for reducing stress, which include mindfulness-based interventions, breathing exercises and guided imagery.

Psycho-education

Psycho-education involves informing the woman about her mental health status in non-technical and understandable terms, and includes the management options available. When appropriate, it is important that she understands that her feelings and responses to the difficult situation are part of an accepted range of emotional experiences. Where a women has a mental illness, it is helpful to emphasise that the illness is not her fault or a result of any personal weakness. Further, it should be stressed that recovery or improvement of symptoms and functioning is highly probable with appropriate management and follow-up.

Early treatment

Women with CMDs need to be treated as early as possible to reduce the consequences described above and the risk of suicide. Women with a history of CMDs may need to be treated prophylactically. The first line of treatment for mild to moderate CMDs would be use of one of the talking therapies. There are several types of evidence-based talking therapies that have shown benefit for people with CMDs, including women in the perinatal period. These include problem-solving therapy, cognitive behavioural therapy and interpersonal therapy. Research has demonstrated that lay health workers, well trained and supervised, may successfully provide these therapies. For women with moderate to severe CMDs or those who do not adequately respond to talking therapy, medication or more specialised care may be warranted.

Antidepressants, especially selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have been found to be generally safer than the possible risks to the fetus and breastfeeding infant of a mother with untreated CMDs.[21] Women who are stable on antidepressant medication when they become pregnant should continue on the medication as before, as switching types or discontinuing medication may cause serious relapse. Those who develop a CMD can safely be commenced on an antidepressant. Care should be taken when SSRIs are introduced, as these may initially increase the risk of suicide. There are limited data on the safety of tricyclic antidepressants on the fetus, as an overdose may be lethal. They lead to increased sedation compared with the SSRIs, but have the benefit of not causing agitation when started. Antidepressants treat both depression and anxiety.

Sulpiride (Eglonyl), which is commonly used to improve breastfeeding in agitated and distressed mothers, should usually be avoided, as it increases the risk of suicide in some women and does not treat the underlying depression.

Holistic management

It is important that women be managed as holistically as possible. This includes management of underlying causes or factors that exacerbate CMDs. It may be critical to arrange careful referrals to social services, appropriate non-governmental organisations and community-based services. Food security and physical security need to be prioritised. Linking vulnerable women with supportive social networks may be extremely valuable. Follow-up and case management will support uptake of care and recovery. Although this work may be time consuming initially, it is a useful investment in the long-term physical and mental health outcomes for both mothers and their offspring. Further, birth companionship has been shown in several clinical trials to have a wide range of physical and mental health benefits.

Conclusion

Common mental disorders in the perinatal period affect 20 - 40% of women in SA. This may be due to the multiple risk factors facing women in this country, especially those living in poverty and with violence. Ideally, all antenatal clinics should screen for CMD and provide integrated care to pregnant women. CMDs can be detected and effectively managed, thereby reducing a large range of possible adverse consequences for mothers, their children and their family.

References

1. Lund C, Breen A, Flisher AJ, et al. Poverty and common mental disorders in low and middle income countries: Λ systematic review. Soc Sci Med 2010:7 L(3):517-28. http://dx.doi.org//10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.04.027 [ Links ]

2. Lund C, de Silva Μ, Plagerson S, et al. Poverty and mental disorders: Breaking the cycle in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2011:378(9801):1502-1514. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(I1)60754-X [ Links ]

3. Saxena S, Lhornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: Scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet 2007:370(9590):878-889. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61239-2 [ Links ]

4. Stein A, Pearson RM, Rapa Ε, et al Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet 2016:384(9956):1800-1819. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61277-0 [ Links ]

5. Fisher J, Cabral de Mello Μ, Patel V, et al Prevalence and determinants of common perinatal mental disorders in women in low- and lower-middle-income countries: A systematic review. Bull World Health Organ 2012:90(2):139-149G. http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.ll.091850 [ Links ]

6. Van Heyningen T, Myer L, Onah M, Tomlinson M, Field S, Honikman S. Antenatal depression and adversity in urban South Africa. J Affect Dis 2016:203:121-129. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.05.052 [ Links ]

7. Herman AA, Stein DJ, Seedat S, Heeringa SG, Moomal H, Williams DR. The South African Stress and Health (SASH) study: 12-month and lifetime prevalence of common mental disorders. S Afr Med J 2009:99(5):339-344. [ Links ]

8. Freeman M, Nkomo N, Kafaar Z, Kelly K. Mental disorder in people living with HIV/AIDS in South Africa. S Afr J Psychol 2008:38(3):489-500. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/008124630803800304 [ Links ]

9. Rochat TJ, Richter LM, Doll HA, Buthelezi NP, Tomkins A, Stein A. Depression among pregnant rural South African women undergoing HIV testing. JAMA 2006:295(12):1376-1378. http://dx.doiorg/10.1001/jama.295.12.1376 [ Links ]

10. Cook JA, Grey D, Burke J, et al. Depressive symptoms and AIDS-related mortality among a multisite cohort of HIV-positive women. Am J Public Health 2004:94(7):1133-1140. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/ajph.94.7.1133 [ Links ]

11. Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Gray GE, Mclntryre JA, Harlow SD. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet 2004:363(9419):1415-1421. http://dx.doiorg/10.1016/s0140-6736(04)16098-4 [ Links ]

12. Barnet B, Joffe A, Duggan AK, Wilson MD, Repke JT. Depressive symptoms, stress, and social support in pregnant and postpartum adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1996:150(1):64-69. http://dx.doLorg/10.1001/archpedil996.02170260068011 [ Links ]

13. Barnet B, Liu J, deVoe M. Double jeopardy: Depressive symptoms and rapid subsequent pregnancy in adolescent mothers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008:162(3):246-252. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.60 [ Links ]

14. Hodgkinson SC, Colantuoni E, Roberts D, et al Depressive symptoms and birth outcomes among pregnant teenagers. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2010:23(1): 16-22. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2009.04006 [ Links ]

15. Block RW, Saltzman S, Block SA. Teenage pregnancy: A review. Adv Pediatr 1981:28:75-98. [ Links ]

16. Siegel RS, Brandon AR Adolescents, preganancy and mental health. Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2014:27(3):138-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2013.09.008 [ Links ]

17. Yookyong L. Early motherhood and harsh parenting. The role of human, sociak and cultural capital Child Abuse Neglect 2009:33(9):625-637. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.02.007 [ Links ]

18. Kirmayer LJ, Narasiah L, Muñoz M, et al Common mental health problems in immigrants and refugees: General approach in primary care. Can Med Assoc J 2011:183(12):E195-E165. http://dx.doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.090292 [ Links ]

19. Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression: Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med 1997:12(7):1525-1497. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/J.1525-1497.1997.00076.X [ Links ]

20. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh postnatal depression scale. Br J Psych 1987:150(6):782-786. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782 [ Links ]

21. Du Tort E, Thomas E, Koen L, et al SSRI use in pregnancy: Evaluating the risks and benefits. S Afr J Psychiatry 2015:22(2):48-52. http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAJP5S7 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

R E Turner

roseanne.turner@uct.ac.za