Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.106 no.11 Pretoria nov. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2016.V106I11.10683

RESEARCH

Is South Africa advancing towards National Health Insurance? The perspectives of general practitioners in one pilot site

R SurenderI; R van NiekerkII; L AlfersIII

IDPhil; Department of Social Policy and Intervention, Social Sciences Division, Oxford University, UK

IIDPhil; Institute of Social and Economic Research, Faculty of Humanities, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa

IIIPhD; Institute of Social and Economic Research, Faculty of Humanities, Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND. The launch of the National Health Insurance (NHI) White Paper in December 2015 heralded a new stage in South Africa's advancement towards universal health coverage. The 'contracting in' of private sector general practitioners (GPs), though only one component of the overall reformed system, is nevertheless crucial to address staff shortages and capacity, and also to realise the broader vision of a single unified, integrated system.

OBJECTIVE. To report on the views and experiences of GP providers tasked with implementing the reforms at one pilot site, Tshwane District in Gauteng Province, providing an insight into the practical challenges the NHI scheme faces in implementation.

METHODS. The study was qualitative in nature, using a combination of convenience and purposeful sampling to recruit participants. A thematic analysis of the data was conducted using Nvivo 10 software.

RESULTS. The overall experiences of the GPs exposed a number of problems with the pilot. These included frustration with lack of appropriate infrastructure and equipment in NHI facilities, difficulties integrating into the facilities and lack of professional autonomy, as well as unhappiness with contracting arrangements. Despite strong support for the idea of NHI, there was general scepticism that private doctors would embrace the scheme on the scale required.

CONCLUSION. The study suggests that the current pilots are still a long way from the vision of a single, integrated health system. While it may be argued that the pilots are not themselves the completed NHI, the findings suggest that it will take much longer to establish than the timeline envisaged by government.

The launch of the long-awaited National Health Insurance (NHI) White Paper (WP)[1] in December 2015 heralded a new next stage in South Africa (SA)'s advancement towards universal health coverage -arguably, the most radical health reform in the country's history. The political vision is the creation of an equitable, universal and integrated healthcare system, underpinned by the values of social solidarity and redistribution. In order to achieve this health system transformation, the proposals intend a complete reconfiguration of the necessary funding and service delivery mechanisms.

A new NHI Fund will provide finance for healthcare and will enter into contracts with public and private hospital specialists and general practitioner (GP) practices to deliver services free of charge at the point of use to every SA citizen and legal resident. 'Primary healthcare re-engineering' forms a central plank of the new system and is characterised in the WP as 'the heart beat of NHI'.[1] GPs are expected to play a key role in providing integrated health services at primary level, taking on complicated and chronic cases that are beyond the scope of nurse-led services[1] and acting as gatekeepers by minimising onward referrals to higher levels of the health system. This role will be reinforced with clinical specialist support teams and school-based services, also deployed at district level. The contracting of private sector GPs into the public health system, though only one component of the overall reformed system, is nevertheless crucial, both to address the immediate significant staff shortages and capacity, and to realise the broader vision of a single integrated system. The WP therefore acknowledges that private sector doctors are 'an essential step' in implementing a successful NHI.

NHI will be implemented over a 14-year period from April 2012, with pilots in 11 selected districts from April 2012.[2] They will test interventions that are necessary for implementing NHI and assess the feasibility of the proposals and the implications of scaling up the innovation nationally. This includes strategies for engaging private sector resources for public purposes. Although the final arrangements for engagement with private sector GPs are still being determined, early research suggests that doctors have multiple concerns around remuneration, state control, increased workload, clinical autonomy and diminished quality of care and working conditions - and that the government will face significant challenges in garnering their support.[3]

This article reports the findings from qualitative research into the views and experiences of recently contracted GP providers tasked with implementing the reforms at one pilot site. The findings provide an insight not only into possible practical challenges the NHI scheme may face in implementation, but also into the broader political challenge that policymakers face. At the time of the fieldwork (mid-2015), 75 GPs had been recruited into the pilot - the largest number of recruits in any site. Also, at the time of this study, the National Department of Health (NDoH), which had been struggling to recruit sufficient numbers of GPs, had recently contracted with the Foundation for Professional Development (FPD) to take over recruitment and performance management of GPs in pilot sites. Established by the South African Medical Association (SAMA) in 1997, the FPD is a private (non-profit) organisation engaged in 'higher education capacity building and health system strengthening'.[4]

Methods

Fieldwork was conducted between April and June 2015 in 17 clinics operating in the pilot district. It was selected as the study site because of its relatively advanced state compared with other regions, particularly with regard to the number of doctors who had contracted into the scheme (over a quarter of the 250 doctors nationally who were then participating in NHI).[5]

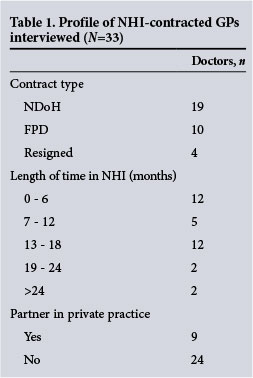

A combination of convenience and purposeful sampling was used to recruit participants. A total of 55 interviews were conducted, of which the majority (33) were with GPs contracting with the pilot. This article reports the findings from the GP interviews only. As with most qualitative studies, the sampling criteria were purposeful rather than random and the goal was to identify the contextual conditions favourable to certain policy outcomes rather than to establish causality between variables.[6] Efforts were made to interview as wide a range of doctors as possible in terms of age, gender and race, and to include clinics in a variety of geographical (urban, periurban) areas serving communities with different socioeconomic profiles.

Interview guides were developed and administered by the researchers and examined the scheme's administration, quality of care and working conditions. They also included broader questions about the future prospects of the NHI, perceptions about private v. public sector medicine, and barriers to more doctors participating in the scheme. Interviews lasted on average 45 minutes, were conducted in English in private spaces in clinic settings, and were digitally recorded. Interviews stopped when data saturation was reached, i.e. when it was judged that no significant new data would emerge from further interviews. A thematic analysis was applied to the coded interview transcripts using the Nvivo software package, version 10 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Australia). Informed consent was obtained in writing from all participants, and any information that might identify individuals was deleted to ensure their anonymity.

Results

Table 1 shows the profile of NHI-contracted GPs interviewed.

Motivation for joining the scheme

Several doctors spoke positively about their commitment to the NHI vision as the primary driver of their involvement with NHI. Some articulated this in political or ideological terms, though most simply used words such as 'giving back' and 'serving the community'. However, most respondents (70%) outlined more pragmatic and instrumental motivations for contracting with NHI, and this was reflected in the profile of the recruits, a large number (65%) of whom described themselves as in 'transition' of some sort. Examples included having just completed their community service and starting up their own practice, or being 'in between jobs', in early retirement or simply in need of additional income. A large number of female GPs who were parents welcomed the flexibility and work/life balance NHI afforded. Particularly striking was that relatively few doctors had come from private practice, as envisaged in the WP. A large proportion of new NHI recruits were upfront that they had previously been working for the FPD and changes in the funding structure of the organisation had meant that they had little choice with regard to transition to NHI when the FPD took over the pilot contract. Several of them were reluctant recruits, given the divergence between their current front-line clinical work and their previous work in public health, epidemiology or health systems strengthening.

GPs' overall assessment of NHI

Irrespective of past background or motivation for contracting, overall perceptions of the achievements and shortcomings of the scheme were relatively consistent. A minority of doctors (29%) were positive about the discernible impact that NHI was having on expanding access to previously underserved communities. According to these respondents, the presence of GPs in clinics allowed more patients to be seen and also drove up standards of care. Examples included better local management of patients with chronic conditions, raising the skills and performance of nursing staff through teaching and mentoring, and improvements in administrative systems such as appointment systems and organisation of patient files.

However, most commentary about the quality of care being provided in the pilot site was negative. Poor infrastructure and lack of basic equipment (sutures, sterile packs and syringes), especially problems with stock-outs and lack of medication, were the biggest frustrations, with many doctors bringing in their own personal equipment to overcome shortages. Doctors relayed feelings of 'embarrassment' and 'powerlessness' about their inability to provide decent care, and many were scathing that the lack of resources undermined the NHI goal of reducing referrals to the hospital sector. There were repeated accounts of unnecessary referrals to hospitals for minor procedures that GPs should have been able to deal with if they had sufficient equipment. A particularly persistent complaint was the strict requirement to prescribe only from the Essential Drugs List (EDL), even in the context where GPs felt this reflected suboptimal treatment. Numerous objections were made about the narrow range of drugs available, especially antibiotics, and the rigidity of the protocols.

Related to this was the common complaint from doctors that they felt they were acting as 'glorified nurses' rather than utilising their clinical training. In contrast to the envisaged model of 'triage' (nurses only referring patients who they could not assist 'up' to GPs), the reality of staff shortages, lack of resources and pressure of long queues resulted in doctors simply providing the same routine services as nurses (blood and urine tests, blood pressure monitoring, dispensing and packaging medication). Doctors across all clinics spoke of 'seeing patients straight off the bench' and described their role as 'now working as a primary healthcare nurse'. These feelings were often compounded by the tensions and 'power struggles' between different health workers, as GPs were being integrated into what had previously been nurse-led clinics. Several doctors (especially younger females) resented being 'managed' by nurses and pharmacists.

GPs' morale was not helped by the poor physical infrastructure, lack of administrative support and stressful working conditions. Accounts of lack of air conditioning or proper ventilation and concerns about tuberculosis (TB) infection, having to share offices with nurses and 'fetching and carrying patient files' were frequent. There were also recurrent tales about hostility and aggression from patients (now with raised expectations) frustrated at long queues. Misunderstandings about why doctors (who were contracted only for specific sessions) were leaving at midday resulted in several reports of abuse and even violence from patients.

Experience of the NHI contract

In contrast to earlier studies,[3] complaints about the remuneration offered by the NHI contract were not particularly strident. Nevertheless, the basic rate of ZAR381 per hour was considered acceptable by only 40% of respondents, who felt that it compared reasonably well with alternative public sector salaries. To some extent this reflects the particular profile of the GPs who were contracting with the pilot, many of whom had been out of work, in the public sector, or in smaller practices. Almost all respondents, however, acknowledged that compared with 'real private sector rates' the remuneration was very low and would be insufficient to attract most private GPs.

There was, however, considerable dissatisfaction with other terms of the contract, including the lack of benefits (health insurance, maternity leave, indemnity cover) and constraints on travel allowances (with only journeys up to a radius of 50 km covered). Since the transfer from the NDoH to FPD-administered contracts, the biggest concern revolved around the intention of the FPD to reduce the flexibility of doctors in determining their own hours working for an NHI clinic. This flexibility had been a major appeal for the majority of respondents, allowing them to balance child care, studies or their own private work. New attempts by the FPD to require doctors to work full time appeared to be deeply unpopular with the GPs, with several threatening to leave once it was enforced.

Sustainability of the model

Despite considerable personal support for the NHI on the part of many respondents, there was general scepticism that private doctors would really embrace the scheme on the scale that was required. Rates of remuneration, lack of equipment, poor physical conditions and restricted prescribing from the EDL were the main obstacles cited. Some doctors, however, also noted that there were significant divides in terms of the expectations and experiences of working with patients using the public and private sectors. Whereas private patients were frequently well informed, well resourced and proactive about their health (often castigated as the 'worried well'), clinic patients tended to be extremely sick by the time they presented. Limited experience working with HIV and TB conditions and lack of cultural and contextual familiarity with adherence to treatment or patient belief systems and use of traditional healers would be a challenge to many private providers. Finally, some respondents acknowledged that NHI represented an economic threat to the livelihoods and autonomy of most private practitioners and, in order to protect their own self-interests, private sector GPs would not want to participate.

Equally, however, many of the respondents in this study acknowledged that they themselves were unlikely to remain in the pilot for long. A range of factors such as 'burnout' or anticipated changes in the FPD contracts or their own circumstances led many to predict that 'I don't think any of us will be willing to stay here for a long time.' Finally, several doctors acknowledged a serious mismatch in the availability of and need for health services. Most of the doctors in this study were only prepared to work near to urban centres where their homes, children's schools or private practices were located and were therefore unwilling to travel to more distant or remote rural areas. Consequently, the distribution of GPs among the six subdistricts within the pilot was uneven, ranging from 20 - 25 GPs in subdistricts closest to Pretoria to only 5 - 6 GPs in the subdistricts that were most distant.

Discussion

The decision by government to invest in key pilot districts to develop the human resource capacity necessary for NHI was both strategic and practical. However, despite some progress and the many changes underway, the recruitment of private sector GPs into pilot sites has been challenging, as indicated in this study. Although one of the best-resourced and best-capacitated provinces and the largest pilot, there were still only 47 'NHI' GPs contracted with the study pilot at the beginning of 2015, although this number was subsequently bolstered with an additional 28 'FPD' recruits (75 GPs contracted in total) as the research unfolded (NDoH - unpublished data, 2015).

Unfortunately this case is not atypical, and the record of private sector GP contracting has not been promising across the 11 sites. The government's initial target to recruit 600 GPs in the first year was drastically missed, with less than 100 GPs signing contracts between 2013 and 2014. Revised targets to have 900 GPs nationally contracted into NHI by March 2015 equally failed, with approximately 200 out of the 8 000 private sector GPs in SA joining up.[7] Particularly depleted is the Eastern Cape's OR Tambo District, where only one doctor has contracted, and the Northern Cape's Pixley kaSeme District, with only 10 recruits by 2015.[5]

In this context it is important to question whether the 'contracting out' of recruitment (and training) of GPs to a private third-party agency (the FPD) may not only be indicative of the challenges faced but in turn compound them, if the terms and conditions offered are unfavourable to GPs. Going forward, it will be important to examine whether an independent professional organisation of this kind will possess the required motivation and organisational force to convey the values of social solidarity, justice and equity that underpin the NHI WP.

It was notable in this pilot that the scheme is so far mostly attracting particular categories of clinician - those recently graduated, retired or in transition. Many of the doctors who had signed up were newly graduated or had relatively little general practice experience. Furthermore, rather than recruiting from large well-resourced private sector practices as intended, this has largely been a reshuffling exercise within the public sector, with the majority of NHI recruits coming from public sector hospitals and primary care practices.

It could be argued that the low number of GP recruits was predictable considering the opposition NHI has faced from the profession's major medical associations, including SAMA[8] and the South African Private Practitioners Forum.[9] However, evidence from this study suggests that it may be the substantive reality of poor working facilities and conditions on the ground rather than professional politicking that is driving clinician behaviour. It has been estimated that only 2% of health facilities in the Eastern Cape pilot (OR Tambo District) had the necessary equipment, medicines and space to allow private GPs to work in them - even if they were willing. [10] Moreover, in addition to problems of recruitment, nationally NHI pilots are reportedly struggling to hold onto many of the doctors who have joined. Reflecting many of the concerns evident in this case study, doctors have cited poor working conditions (long hours and poor equipment), ineptitude of the provincial health department[10] and lack of flexibility in contracts as principal challenges to retention.[7]

Perhaps most discouraging is the finding from this research that even when GPs have been recruited to NHI clinics, inadequate infrastructure and medication mean that often suboptimal care is being provided. On launching the WP, health minister Motsoaledi described NHI as 'a major transition in health', predicting that 'it is going to change healthcare irreversibly'. However, given that most doctors in this study reported that they were providing basic nursing services rather than physician care, it is salient to question whether the placement of more GPs in under-resourced public clinics can amount to 'a re-engineered NHS'. It is true that access to primary care services has been expanded for a previously underserved segment of the population and that outreach programmes, health education and preventive health measures, such as the community and school health teams, are reportedly functioning well in some districts.'111 Nevertheless, this is a long way from the vision of a high-quality, integrated system of national healthcare utilised by the whole population. And while it may be reasonable to argue that the pilots are not themselves the ready and completed NHI but merely the stepping stones towards a matured and established system, the findings from this study suggest that more time alone will not resolve the current problems.

It is particularly concerning that failure to attract the required number of GPs has had negative effects on the NHI's budget. A third of pilot sites failed to spend their allocated grants by July 2013, a year after they were awarded, and only a small proportion of the previous allocation for the NHI - 9% of ZAR388 million - had been spent by December 2014,'71 resulting in a cut of ZAR767 million from the National Health Grant over the next 3 years. This reality has led to a growing call by some that, ultimately, in order to make the necessary progress, a more fundamental reform of healthcare is essential - in particular, additional finance and resources are required. [12] Certainly, if the evidence from this site is indicative of what is happening in the wider pilot programme, there must also be more engagement with the views and experiences of clinicians on the front line if the government's agenda for healthcare reform is to be realised.

Conclusion

The study suggests that the current pilots are still a long way from the vision of a single, integrated health system. While it may be argued that the pilots are not themselves the completed NHI, the findings suggest that it will take much longer to establish than the timeline envisaged by government.

References

1. Republic of South Africa. National Health Insurance for South Africa: Towards Universal Health Coverage (The White Paper), 2015. http://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/National_Health_Insurance_White_Paper_10Dec2015.pdf (accessed 10 January 2016). [ Links ]

2. Republic of South Africa. National Health Insurance in South Africa: Policy Paper (The Green Paper), 2011. http://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/nationalhealthinsurance.pdf (accessed 25 June 2015). [ Links ]

3. Surender R, van Niekerk R, Hannah B, et al. The drive for universal healthcare in South Africa: Views from private general practitioners. Health Policy Plann 2014;3(6):759-767. DOI:10.1093/heapol/czu053 [ Links ]

4. Foundation for Professional Development. Annual Report. Pretoria: FPD, 2015. http://www.foundation.co.za/FPD/aboutfpd/PDFs/annual%20reports%20pdfs/AR%202014_2015.pdf (accessed 1 January 2016). [ Links ]

5. Mkhwanazi A. NHI: Poor conditions scare GPs away. Health-E News, 2 June 2015. http://www.health-e.org.za/2015/06/02/gps-scared-away-from-nhi-pilots-by-poor-conditions/ (accessed 22 June 2015). [ Links ]

6. Mahoney J, Goertz G. A tale of two cultures: Contrasting quantitative and qualitative research. Polit Anal 2006;14(3):227-249. DOI:10.1093/pan/mpj017 [ Links ]

7. Khan T. Why the NHI pilot is failing. Rand Daily Mail, 26 March 2015. http://www.rdm.co.za/business/2015/03/26/why-the-nhi-pilot-programme-is-failing (accessed 22 June 2015). [ Links ]

8. Loggerenberg D. NHI: Economic suicide for doctors. News 24, 2013. http://www.health24.com (accessed 5 July 2013). [ Links ]

9. Archer C. NHI: Let's talk about this revolution. Mail & Guardian, 7 February 2014. http://mg.co.za/article/2014-02-06-lets-talk-about-this-revolution (accessed 15 May 2015). [ Links ]

10. Khan T. Most districts in the NHI study have failed to spend their budgets. Business Day Live, 24 July 2013. http://www.bdlive.co.za/national/health/2013/07/24/most-districts-in-nhi-study-have-failed-to-spend-their-budgets (accessed 16 February 2016). [ Links ]

11. Cullinan K. Doing things differently in KZN. Health-E News, 22 June 2015. http://www.health-e.org.za/2015/06/02/nhi-doing-things-differently-in-kzn/ (accessed 22 June 2015). [ Links ]

12. McIntyre D. To NHI or not? And if so, what, when, why and how? Public Health Association of South Africa, 31 August 2015. https://www.phasa.org.za/to-nhi-or-not-and-if-so-what-when-why-and-how/ (accessed 16 February 2016). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

R Surender

rebecca.surender@gtc.ox.ac.uk

Accepted 17 May 2016