Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.106 no.11 Pretoria nov. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2016.v106i11.12069

CME

Physical and sexual violence against children

A B van As

MB ChB, MMed, MBA, FCS (SA), PhD; Trauma Unit, Division of Paediatric Surgery, Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Violence against children represents a sobering reality for South African health professionals. Dealing with violence against children can easily take a heavy toll on health professionals' health, often resulting in compassion fatigue, or secondary traumatic stress, which is characterised by a blunted response to patients' suffering, in turn causing them secondary traumatisation. This article prepares health professionals in choosing the most appropriate and comfortable management for these unfortunate young victims of violence.

All health professionals are responsible for the detection, treatment, and reporting of child abuse. Most severe (including lethal) abuse occurs in children <3 years old. Africa's homicide rate for under-5 children is more than six times the incidence in Western countries.[1] Unfortunately, the magnitude of the problem has been obscured by differing legal and cultural definitions of abuse and poor reporting and recording of cases. According to the World Health Organization, 'Child abuse or maltreatment constitutes all forms of physical and/or emotional ill-treatment, sexual abuse, neglect or negligent treatment or commercial or other exploitation, resulting in actual or potential harm to the child's health, survival, development or dignity in the context of a relationship of responsibility, trust or power'.[2]

Role of the healthcare worker in child abuse

Health professionals should (i) recognise child abuse; (ii) accurately document all clinical findings (physical and/or psychological); (iii) provide appropriate treatment for injuries sustained; and (iv) report cases to the appropriate authorities.

Treatment varies from analgesics to extensive surgical procedures and placement in institutions. Apart from medical treatment for the child, support for the patient and family should be provided. To take an adequate history can be very complicated, as parents or caregivers are often in an anxious state. It might be very difficult to establish whether the injury was accidental or non-accidental. However, the health professional's role is to provide an accurate diagnosis, not to play detective. The diagnosis might be very difficult, but a number of circumstances should raise suspicion of child abuse (Table 1).

Types of violence against children

Physical abuse (non-accidental injury) denotes deliberate infliction of injury. Child sexual abuse is the use of a child for sexual gratification. This also includes (i) touching, fondling, or other inappropriate contact with a child's genitals or breasts; (ii) masturbation of a child by an adult or vice versa, and masturbation of an adult in the presence of a child; (iii) body contact with an adult's genitals; (iv) exhibitionism; and (v) pornography, including photography and erotic talk. Note that most of these types of violence against children will leave no physical signs. Failure to thrive due to nutritional deprivation most commonly occurs within the first 2 years of life. Approximately 50% of all failure to thrive in this age category is due to parental neglect. Intentional drugging or poisoning refers to giving a prescribed drug that was not intended for the child. Medical care neglect occurs when a child's disease worsens owing to parental ignorance of the condition. Safety neglect refers to a lack of supervision, especially in younger age categories. Emotional abuse occurs when the child is repeatedly blamed, criticised or rejected by parents and/or caregivers. It includes verbal abuse, which is common and difficult to prove. Finally, organised abuse is a form of organised crime, often involving multiple victims and perpetrators. Paedophilic and pornographic rings are major contributors, but it also includes cult-based abuse, with spiritual or social objectives.

Physical violence against children

Child abuse commonly causes childhood death, second only to sudden infant death syndrome in babies <6 months old. Although culture or socioeconomic status may be associated with child abuse, many studies indicate that abuse occurs among all income categories and all cultures.[3] The younger the child, the bigger the risk. Younger children are at greatest risk because they are more demanding, defenceless, and non-verbal. One-third of physical abuse occurs in children <6 months of age, another third in those between 6 months and 3 years of age, and the remaining third in those > 3 years of age. At particular risk are male children, those born prematurely, and stepchildren.[3]

Non-accidental injury results from a deliberate action by a person who intentionally threatens, attempts, or inflicts physical harm on another. Accidental injuries result from unforeseen events that cause external trauma to the body, without the intent to cause harm. The exact circumstances surrounding assault are often unclear. Some cases involve the so-called shielding phenomenon. This encompasses a broad spectrum, from the child sustaining injuries as an innocent bystander to cases where an adult positions the child in self-defense against an attacker.[4] Injuries such as stab wounds are particularly suggestive of shielding, because it is unlikely that anyone would deliberately assault a child with a weapon. Most children admitted with firearm-related injuries are victims of 'stray bullets'.[5]

Causes of child abuse and predisposing factors

Research indicates that >90% of abusive parents have no psychological problems or a criminal nature. Instead, they tend to be lonely, unhappy, and angry adults under tremendous stress. Additional stressful factors include a breakdown of family structure, poverty, financial need, unemployment, intimate partner violence, being a single parent, and substance abuse. There is also an intergenerational factor, as >90% of abusing parents may have been a victim of violence during their own childhood.[6]

Diagnosing child abuse

There are many ways to establish a diagnosis of non-accidental injury in children. The first is when the child readily cites a particular adult as the assailant. The complaint must be taken very seriously, and every case thoroughly investigated. Unexplained injury should prompt a consideration of child abuse, particularly when parents are reluctant to explain the nature of the accident. For instance, parents might claim that they 'just found the child like that', or 'the child might have fallen down', or 'someone else might have hit the child'. The majority of the parents know to the minute where and when the child was hurt. A changing or discrepant history of how the trauma occurred is also suggestive of child abuse.

The suspicion of child abuse increases when the history provided does not explain the severity of the physical injuries. For instance, a child who fell from a bed and yet is covered with bruises is unlikely to have suffered such injuries from the stated mechanism. Another is a parental claim that the child 'bruises so easily', which is usually misleading, especially when no new bruises appear during hospitalisation. Claims of self-infliction in children should be treated with suspicion; for example, reporting that a young baby has 'rolled over her arm and fractured it'. Similarly, shifting the blame for the injury to a third party (often absent and untraceable) may also indicate child abuse.

Delayed presentation is a common feature of abuse injuries. Normally parents bring their child to hospital within 24 hours of an injury. After child abuse, however, a delay is rather common. Finally, repetitive injuries in a child may indicate child abuse.

Skin lesions

Skin lesions can occur everywhere. Bruises on the buttocks and lower back may relate to corporal punishment, and bruises on the face are often secondary to being hit. Other typical findings are grip marks, pinch marks, and circumferential bruises. Defining the exact age of the injuries can be controversial. Most light skin lesions initially display a red colour, followed by a reddish-purple period within 24 hours, which then gradually progresses to a predominantly purple lesion (often referred to as blue) over the next week. Discoloration to yellow/green/brown is due to degradation of haemoglobin and occurs over 1 - 3 weeks.

Burns

Approximately 10% of physical abuse involves burns. Typical lesions found in child abuse are cigarette burns and so-called stocking/glove injuries from immersing toddlers in hot water.[7]

Head injuries

The incidence of abusive head injury ranges from 17/100 000 to 40/100 000. Infants 0 - 3 months of age are the largest group.[8] Approximately one-third of abusive head injuries are not recognised at the initial visit to a healthcare institution. Although non-accidental head trauma in children <3 years of age is difficult to diagnose, one should maintain a high index of suspicion. The spectrum of head injury can range from skull fractures to severe lethal intracranial bleeding and brain atrophy. Subdural haematomas may also be the result of shaking. The rapid acceleration and deceleration of the shaking head appear to tear bridging veins, with resulting bleeding and subdural haematomas, often bilaterally. Another common finding is diffuse cerebral brain swelling with loss of normal grey-white matter differentiation and retinal haemorrhages.[9]

Skeletal injuries

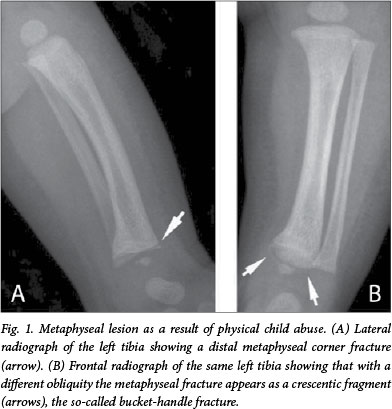

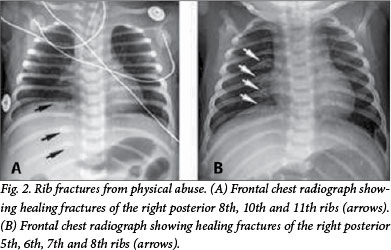

Fractures in small children are rare. In all patients <3 years old, the occurrence of a fracture without an adequate history should prompt suspicion of child abuse. Approximately one-quarter of physical abuse cases involve skeletal injury. The long bones are involved in two-thirds of fractures, which can be spiral or transverse. Certain fractures are almost pathognomonic of child abuse, such as a chip fracture (corner or bucket-handle fracture) of the long bones (Fig. 1). This injury occurs owing to avulsion of the corner of the metaphysis from the periosteum during wrenching injuries to the long bones. Approximately 10 days after the injury, calcification of the subperiosteal bleeding creates the classic double cortex line. In all cases of suspected child abuse, a skeletal survey should be obtained. This comprises a combination of radiographs of the chest, skull and extremities, only in the anteroposterior direction. Repeated abuse may manifest as old rib fractures with callus formation in different phases of healing (Fig. 2). A radionuclear bone scan is a more sensitive method to detect old injuries, but is unreliable in children <1 year of age.

Differential diagnosis

Certain conditions may be mistaken for abuse (and vice versa), including (i) birth trauma: should be evident from the birth history; (ii) congenital syphilis: chronic periosteal reaction combined with metaphyseal widening and positive blood tests; (iii) osteogenesis imperfecta: multiple fractures, blue sclerae, osteopenia; (iv) rickets: renal disease, bowed long bones, blood abnormalities; (v) scurvy: poor wound healing, bleeding gums, petechiae; (vi) bleeding disorders: haemophilia, meningococcaemia; and (vii) skin diseases: impetigo, chickenpox, scaled skin syndrome, which may mimic burns. Genuine accidental trauma may also present, which can be diagnosed by the history, pattern of injury, and interaction with parents or caregivers.

Management of injuries

The initial stabilisation of the physically assaulted child uses an ABC approach, as with any injured child.[10] It consists of (i) primary survey with resuscitation; (ii) secondary survey with emergency treatment; and (iii) transfer to definitive care, where the abused child can receive integrated and holistic treatment. This includes medical treatment, the necessary medicolegal investigations and psychological support. This is crucial to avoid unnecessary (and traumatic) repetitive physical examination and/or repetitive taking of the medical history. While treatment is the key priority, be careful to minimise interference with any forensic evidence on the child's clothes or skin. The primary survey consists of ABCDE: Airway with cervical spine control; Breathing with ventilatory support; Circulation with haemorrhage control; Disability with prevention of secondary insult; and Exposure. Useful adjuncts at this stage include chest and pelvic radiographs, initial blood tests (including a cross-match sample), an oro- or nasogastric tube, and a urinary catheter. The initial priority is resuscitation and treatment of immediate life-threatening problems, followed by the secondary survey, in which the child undergoes a thorough head-to-toe examination. Physically abused children often have evidence of older injuries, which must be documented accurately. The final stage of emergency management is transfer to definitive care. This involves appropriate preparation for transfer - either within the hospital or to another unit - and handover to the receiving staff. Accurate handover is essential in cases of suspected or proven physical abuse. Accurate notes facilitate continuity of care.

Sexual violence against children

Abuse should be suspected in any child presenting with perineal injuries or infection. In girls, sexual abuse can be chronic (without signs of fresh injuries, but with absent hymen) or acute (often with fresh physical injuries). Small children often present with a bruised perineum. In the majority of cases, the perpetrator is well known to the child and may be a family member, family friend or neighbour.[11]

Clinicians should be alert to symptoms and signs of child sexual abuse. Recurrent abdominal pain is common in a child unable to express the nature of the injury. Many children are referred only after someone noticed their altered gait or discomfort in walking or sitting. Nearly all children who are sexually abused are threatened (often with their life) not to disclose and are therefore often reluctant to identify the perpetrator. Children may present with a history of painful micturition and recurrent urinary tract infections, while the cause of the infection is sexual violence. Other modes of presentation are faecal soiling and/or retention. Young children presenting with discharge from penis or vagina should be investigated thoroughly and the possibility of sexual violence should be seriously considered. Abnormal wide dilatation of either the vagina or anus is very suspicious, particularly in the presence of genital laceration or bruising. Many abused girl children present to the medical care facility with the single symptom of vaginal bleeding, without any further explanation. All children presenting with sexually transmitted infections should be assumed to be abused until proven otherwise (congenital infections).

Guidelines for examination after abuse

Examination of a sexually abused child must be sensitively performed under optimal circumstances to prevent secondary trauma. Examination should always be done by a qualified health professional. A designated private area is required and a third person (preferably mother or nurse) should be present. It is very important to explain the procedure to the caregiver and child in advance. It is mandatory to perform a full general examination, including weight, height, and nutritional status. The genital examination should only occur once. The overriding principle of physical examination is that the child should be relaxed and co-operative. In cases where this cannot be achieved (and in all cases where surgical repair is required owing to the extent of the injury), an examination under anaesthesia is warranted to determine the exact nature of the injury. Owing to the discrepancy in size between the sexual organs of the perpetrator and those of the victim, penetration rarely occurs in sexually abused children. However, forced penetration in small children can cause a mutilating injury. Absence of penetration does not rule out abuse. In a local study, one-third of the paediatric sexual assault victims had no physical injuries.[12] Bruises and first- and second-degree tears can usually be repaired primarily. However, when there is violation and laceration of the anal sphincter or the rectovaginal septum, a diverting colostomy with washout is needed. When all signs of infection have subsided (usually between 6 weeks and 3 months), the definitive repair can be performed.

The recommended routine investigations for all cases of sexual abuse are the following: (i) full blood count and platelets, international normalised ratio and partial thromboplastin time to exclude a bleeding disorder; (ii) vaginal or penile swab where a discharge is present - send for microscopy, culture, and sensitivity; (iii) blood for a venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test; (iv) HIV serol ogy - post-exposure prophylaxis is continued only for those who test HIV-negative; and (v) photographic documentation for legal purposes. Digital photographs have to be printed, dated, and signed immediately to be useful as evidence in court. The child should be checked for syphilis (VDRL test) and HIV/AIDS. If available, antiretroviral therapy should be initiated. Do not routinely start children on antibiotics, but wait for the results of laboratory tests. Involve social workers from the outset, and contact the child protection unit (police).

Reporting cases of suspected child abuse and court testimony

The numerous pitfalls in dealing with suspected child abuse include (i) relying on the history provided by caregivers or parents regarding the mechanism of injury; (ii) not undressing and examining the whole child; (iii) not being able to mask emotional display while examining the injured child; (iv) insufficient experience in examining children, requiring the child to be re-examined; (v) blaming the caregivers and/or parents instead of supporting them; and (vi) omission of prophylactic antiretroviral therapy after sexual assault. To be accused of child abuse is an extremely painful experience. Some parents react aggressively if medical staff probe the possibility. Parents or care-givers regularly threaten legal action. However, South African (SA) law protects those who report suspected child abuse in good faith. Even though the investigator must be firm to conduct a thorough investigation, due recognition must be given to the possibility that the accused may be innocent. To be as thorough as possible regarding the medical report, an affidavit must be written within 24 hours of severe abuse cases, which might be litigated by court. This will assist doctors considerably at a later stage. Cases often take years to reach court. If the abuse was not well documented or data are missing, the perpetrator nearly always evades justice. All child sexual abuse cases should be investigated by the police. Yet, only 30% of perpetrators end up in court, and only ~7% face prosecution.[12] Importantly, child sexual abuse cases cannot be withdrawn, unlike adult sexual abuse cases, where the victim can change her or his mind.

Conclusion

Violence against children contributes greatly to the burden of disease among children in Africa, who have the unenviable distinction of the highest unintentional injury death rates in the world. In SA, we need to focus on creating and maintaining awareness about the magnitude, risk factors, and preventability of child injuries among policy makers, donors, practitioners, and parents/caregivers.[13] It is high time that the SA government publicly acknowledges the problem of sexual violence against children, establishes systems of reporting and expertise, and ensures a system that protects those who report offences, while swiftly dispensing justice to offenders.[14]

References

1. Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi A, Lozano R. World Report on Violence and Health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002. [ Links ]

2. World Health Organization. Report of the Consultation on Child Abuse Prevention, 29 - 31 March 1999. Geneva: WHO, 1999. [ Links ]

3. Van As AB, Naidoo S, eds. Paediatric Trauma and Child Abuse. Cape Town: Oxford University Press, 2006. [ Links ]

4. Fieggen AG, Wiemann M, Brown C, van As AB, Swingler GH, Peter JC. Inhuman shields - children caught in the crossfire of domestic violence. S Afr Med J 2004;94(4):293-296. [ Links ]

5. Campbell NM, Colville JG, van der Hayde Y, van As AB. Firearm injuries to children in Cape Town, South Africa: Impact of the 2004 Firearms Control Act. S Afr J Surg 2013;51(3):92-96. DOI:10.7196/SAJS.1220 [ Links ]

6. Egeland B. A history of abuse is a major risk factor for abusing the next generation. In: Gelles RJ, Loseke DR, eds. Current Controversies on Family Violence. London: Sage, 1993. [ Links ]

7. Pawlik MC, Kemp A. Children with burns referred for child abuse evaluation: Burn characteristics and co-existent injuries. Child Abuse Neglect 2016;55:52-61. DOI:10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.03.006 [ Links ]

8. Tingberg B, Falk AC, Flodmark O, Hygge BM. Evaluation of documentation in potential abusive head injury of infants in a paediatric emergency department. Acta Paediatr 2009;98(5):777-781. DOI:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01241.x [ Links ]

9. Pressel DM. Evaluation of physical abuse in children. Am Fam Phys May 2000. http://www.aafp.org/afp/2000/0515/p3057.html (accessed 5 October 2016). [ Links ]

10. Advanced Life Support Group. Advanced Paediatric Life Support: The Practical Approach. London: BMJ Books, 2005. [ Links ]

11. Barker J, Hodes D. The Child in Mind. A Child Protection Handbook. London: Routledge, 2004. [ Links ]

12. Van As AB, Whithers M, Millar AJW, Rode H. Child rape - patterns of injury, management and outcome. S Afr Med J 2001;91(12):1035-1038. [ Links ]

13. Peden M, Hyder AA. Time to keep African kids safer. S Afr Med J 2009;99(1):36-37. [ Links ]

14. Jewkes R. Preventing sexual violence: A rights-based approach. Lancet 2002;360(9339):1092-1093. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11135-4 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

A B van As

sebastian.vanas@uct.ac.za