Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.106 no.10 Pretoria oct. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2016.v106i10.11408

CME

Intimate partner violence is everyone's problem, but how should we approach it in a clinical setting?

C Gordon

MB ChB, DMH (SA), Dip HIV Man (SA), MPhil (Health Professions Education), Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a silent public health epidemic in South Africa (SA). Interpersonal violence in SA is the second highest burden of disease after HIV/AIDS, and for women 62% of the former is ascribed to IPV. SA, therefore, has the highest reported intimate femicide rate in the world. IPV has far-reaching consequences, stretching across generations. The cost to the economy and burden on health services are considerable. IPV presents in many ways, cutting across all medical disciplines. Therefore, all medical professionals should be conversant with this issue. This article provides essential, practical steps required for identifying and managing IPV, applicable to any setting. These steps are summarised as six Rs: Realise that abuse is happening (be aware of cues); Recognise and acknowledge the patient's concerns; Relevant clinical assessment; Risk assessment; cRisis plan; and Refer as needed for medical, social, psychological and/or legal assistance.

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is a silent public health epidemic in South Africa (SA), despite progressive reforms in the constitution, legal system, and the implementation of a Victim Empowerment Programme.[1,2] It is also a substantial cause of morbidity and mortality. Despite the human rights ethos of our constitution, far from being a national priority, identifying and managing IPV remain largely unaddressed. When victims seek help, most do so through the healthcare system,[3] yet undergraduate medical curricula persistently produce healthcare professionals unprepared for IPV. As IPV cuts across all medical disciplines, all practitioners should be conversant and competent with this issue.

The Domestic Violence Act

The definition of the SA Domestic Violence Act No. 116 of 1998[4] extends beyond physical and sexual abuse to include 'verbal and psychological abuse; economic abuse; intimidation; harassment; stalking; damage to property; entry into the complainant's residence without consent, where the parties do not share the same residence; or any other controlling or abusive behaviour towards a complainant'. Central to this definition is the perpetrator's desire to subjugate or control the victim, including sexual entitlement, coupled with the belief that this is their right.[4]

Domestic violence can occur in any current or previous relationship - even with a rejected suitor. Although IPV also affects men, this article focuses on IPV against women, as it is widespread.

Potential consequences of IPV

Consequences of IPV are profound and far reaching. SA's female homicide rate is six times higher than global estimates and the highest reported intimate femicide rate internationally.[5,6] IPV harms sexual and reproductive health, causing higher risks of contracting HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs).[1,7] Significantly, victims are less likely to be tested for HIV or to seek medical care, fearing either violence or abandonment if their partner learns that they are HIV-positive.[7] Abused women have higher rates of unintended pregnancies, abortions, miscarriages, preterm deliveries and stillbirths.[8] Furthermore, mental health issues such as depression, suicidality, anxiety and substance abuse are common.[9]

IPV impacts on health-seeking behaviour, resulting in poorer control of chronic diseases. Everyday functioning at work or home can also be affected, including parenting behaviour.[10] No discussion about IPV is complete without considering the children in an abusive household. In the case of perpetrators of IPV, there are high rates of family violence, i.e. abuse of partner and children. Children who witness abuse, or who are themselves abused, can exhibit impaired functioning in a number of different spheres. Child maltreatment is also a well-described risk factor for both experiencing and perpetrating IPV and sexual violence in the future.[10] Impaired health-seeking behaviour extends to child health, as children of abused mothers have a higher under-5 mortality rate.[10]

IPV can have a staggering impact on the economy. One study in the UK estimated largely hidden costs of IPV to be almost GBP23 billion per annum.[11] Medical costs to patients and with regard to the economy arise not only from specific interventions such as mental healthcare or surgery, but also from repeated visits for various nonspecific ailments when the diagnosis of IPV is missed. Workplace-related issues such as poorer overall functioning, absenteeism or abuse of resources (such as repeated phoning of victims by perpetrators) further deepen the economic impact of IPV. Importantly, all these effects may persist long after a woman has escaped the abusive relationship.

Providers of care may assume that asking about IPV is intrusive or offensive. Nevertheless, women appreciate being asked about IPV sensitively, even if they are not being abused.[12] Lack of time is another highly relevant issue in SA, where state services suffer chronic staffing shortages and are overburdened owing to large numbers of patients. Even in private practice, consultation time is limited. Practically, it is difficult to screen every patient, but certain cues and red flags should prompt further exploration.

Why don't women report, and why don t they leave their partner?

Multiple reasons prevent women from reporting abuse. A lack of human rights awareness about IPV, which is consonant with the normalisation of abuse in SA, means that women tend not to frame their experiences as abuse. Access to sensitive care is a further barrier - either as physical access to medical or legal facilities (distance, cost of travel) or a lack of access due to abuse being missed (or ignored) by providers. Poor knowledge about, or faith in, the legal system also contributes to this situation. Furthermore, abusers often intimidate women into not reporting and/or withdrawing cases (perpetrators may threaten harm to children, taking children away, or abandonment).[10]

Reasons for not leaving an abusive situation echo reasons for non-reporting.[13] Many SA women remain profoundly economically disempowered, as they rely on their partners for financial support, which makes escape arduous. However, even well-educated and/or economically independent women have difficulty leaving an abusive relationship. IPV engenders a complex psychological cycle where victims are made to believe that they deserve the abuse. Victims' self-esteem can erode to the degree that they feel fortunate to have a partner, that they would never cope without their partner or are unworthy of finding other partners. Love of the partner and hope of change also contribute to these factors. To complicate matters, women become alienated from health professionals, who label them as irresponsible or unco-operative for not leaving.[11]

How do victims of IPV present?

Patients experiencing IPV commonly present with seemingly unrelated problems, or with multiple 'soft' nonspecific somatic or emotional complaints. Chronic headaches and other pain syndromes, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and substance abuse are cues for possible IPV.[3] Body language is critical - often the only signs being the patient's demeanour or style of interaction. Examples are failure to make eye contact, defensive posture, appearing fearful or anxious, vague and non-committal answers, or declining to answer questions.

Entry points into the healthcare system can be obvious (e.g. emergency rooms), or more subtle, such as repeated visits to primary care centres, mental health services, general practice or other disciplines, where IPV is unlikely to be identified.[1] Further examples of how IPV can present are set out below.

Red flags that could prompt suspicion of IPV[3,9] General

• Chronic pain syndromes (including headaches, backache and pelvic pain)

• Vague, nonspecific somatic complaints, often ongoing

• Poorly controlled chronic conditions

• Poor day-to-day functioning

• An accompanying partner who dominates the conversation, answers on behalf of the patient and/or refuses to leave the room

• Anxious, defensive, submissive, or reluctant engagement with the health professional; poor eye contact; conversely, frankly aggressive behaviour.

Psychiatric

• Depression

• Sleeping problems (unable to fall asleep, waking up in the middle of the night and/or 'thinking too much')

• Anxiety, panic attacks

• Post-traumatic stress disorder

• Substance abuse.

Gynaecological/obstetric

• STIs (acute or chronic), including pelvic inflammatory disease, HIV, syphilis

• Sexual dysfunction

• Unplanned or unwanted pregnancy; miscarriage; termination of pregnancy

• Antepartum haemorrhage

• Injuries

• Repeated injuries, casualty visits or injuries that do not match the description of the cause.

Children

• Any suspicion of child abuse should prompt consideration of IPV in the home.

How to ask the question

Health professionals are often uncertain how to enter into a discussion with patients regarding IPV. The need to open this line of enquiry may happen at any point in the health professional-patient relationship. Firstly, confidentiality should be assured, implying a private setting for the consultation. The clinician's communication skills and body language are important factors in inspiring trust. The following opening questions may be used as needed, keeping in mind that these may also be applicable to past relationships*9

• Are you in a relationship? Are you unhappy in your relationship?

• Is everything all right at home?

• Often when I see patients with this kind of problem (referring to any of the red flag presentations), it may be caused by other problems, e.g. stress. Are you experiencing or have you experienced any kind of difficulties with your partner?

• Has your partner ever threatened you or forced you to do something you didn't want to do?

• Have you ever felt afraid of your partner?

• Does your partner try to control you (such as who you see, how you dress) or refuse to give you money?

The patient's right to refuse to answer, despite being given an adequate opportunity to disclose any abuse, should be respected. Table 1 gives further do's and don'ts in a consultation.

My patient is being abused - now what?

An approach to IPV, using the author's mnemonic, is summarised below:

Should a patient disclose abuse, further action must be taken in accordance with their wishes. Management should encompass empowerment, entailing a thorough health assessment and the provision of information, including options for further care that match the patient's individual needs.

Importantly, ensure that any symptoms (especially vague and nonspecific ones) are not attributable to organic causes. A thorough history and examination should be conducted to exclude these, and further investigation arranged if necessary. Clinical assessment should be guided by the patient's presenting complaint so that appropriate interventions can be made in the correct sequence (e.g. to address STIs, rape, and depression).

A critical facet of managing IPV is to conduct a risk assessment, which necessitates the following questions:

• Does the woman fear for her life or safety?

• Is she being threatened with serious harm?

• Are there children involved in the abuse?

• Is the abuse escalating?

• Is a weapon involved? (Note: this need not be a weapon in the traditional sense; it could be any object that is being used to harm the woman or child)

• Does the partner abuse substances?

Should the woman be at immediate risk of serious harm, she (and her children) should be urgently referred to a shelter or be kept in a facility until the former can be arranged, if she so chooses.

The importance of documentation cannot be overstated,[9] whether these are patient notes, a formal legal document such as the J88 form, or a sexual assault kit form (which a patient would only have if she has opened a case). Specifics of the nature of abuse should be documented. Exact examples should be given, e.g. verbatim quotes from the patient, and/or outlining what has been said or done by the partner. The name of the abuser and nature of the relationship should be stated. A risk assessment should be done and recorded. Physical injuries should be described, measured and illustrated with diagrams, even if this is not done on the specific legal form. Photographs are very useful (e.g. of injuries, damage to property - taken by patients). The patient should keep evidence of harassment, e.g. text messages or emails. Documentation could mean the difference between:

• procuring a protection order or not

• opening a successful case or not

• clinician being subpoenaed for testimony or not (most probably if the documentation is incomplete)

• success or failure of conviction of the perpetrator.

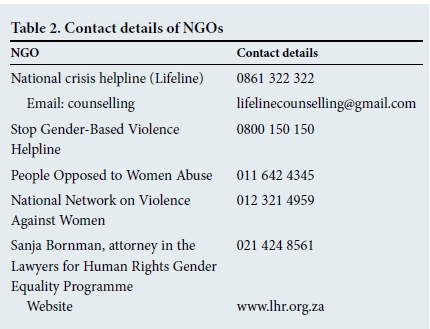

Key to managing IPV is identification and referral to systems that can offer comprehensive care.[3] Referral could include information posters or pamphlets. Patients should be given a referral letter to the mental health nurse at their clinic and contact details of local, relevant non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Some of these are listed in Table 2. Patients may need several follow-up visits at the clinic or practice to attend to all their needs - as with any complex chronic disorder. It is essential that facility/practice managers have updated lists and contact details of local NGOs, shelters and safe- houses (Table 2); doctors should insist on this.

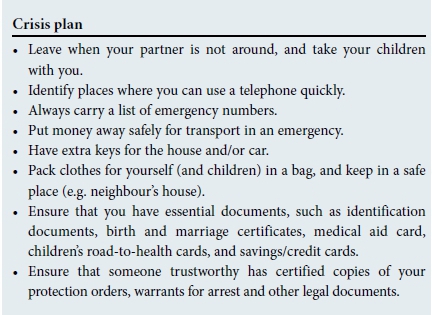

A crisis plan should be made if the patient wishes to leave a partner and/or the residence that they share, as outlined below:'[14]

Legal information

Offer legal information if the patient so desires. (A detailed explanation of the practicalities for securing a protection order is provided in the article by Lopes.'[15])

• Protection order (preferable option):

• obtain from magistrate's court (not police station); therefore not a criminal case unless perpetrator violates the order

• specifically designed as a behaviour modification mechanism to protect against IPV

• available after hours in an emergency

• does not expire.

• A charge (secondary option due to limitations in scope and issues with regard to police attitudes towards IPV):

• laid at police station, opens criminal case

• IPV cannot be reported as a crime, but other charges can be laid; e.g. physical or sexual assault

• in the case of physical violence, a J88 form will be issued, which must be completed by the doctor who first sees the patient. In the case of sexual violence, a rape kit is issued.

What if the patient refuses help?

This is a mentally competent adult's prerogative. Health professionals are only obliged by law to act in cases of child abuse. Our responsibility is to accurately inform the patient to enable her to make informed decisions. Offer follow-up visits at an appropriate facility to assess her situation and state of mind over time and make an effort to provide continuity of care.

Summary

IPV is a chronic and complex medical condition warranting the same degree of care as other serious, potentially life-threatening conditions. It is every health professional's responsibility to detect and manage it. Health professionals have enormous power and influence to either re-empower or further disempower women. A single consultation can affect the person's life profoundly, even if all that is needed is to confidentially talk about the situation. An initial consultation may (or may not) be time consuming, but if done correctly the first time, subsequent visits and management should be much simpler.

REFERENCE

1. Martin LJ, Jacobs T. Screening for Domestic Violence: A Policy and Management Framework for the Health Sector. Cape Town: Institute of Criminology, University of Cape Town, 2003. [ Links ]

2. National Department of Health. National Implementation Plan for the Service Charter for Victims of Crime. Pretoria: NDoH, 2007. http://www.justice.gov.za/vc/docs/2007VCIMPL/2007%20Impl%20Plan%2015%20Nov_CHP_10.pdf (accessed 18 March 2014). [ Links ]

3. Joyner K, Mash R. Recognizing intimate partner violence in primary care: Western Cape, South Africa. PLoS ONE 2012;7(1):e29540. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0029540 [ Links ]

4. Republic of South Africa. Domestic Violence Act 116, 1998 (Act No. 116 of 1998). Government Gazette No. 19537:2. 1998. [ Links ]

5. Seedat M, van Niekerk A, Jewkes R, et al. Violence and injuries in South Africa: Prioritising an agenda for prevention. Lancet 2009;374(9694):1011-1022. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60948-x [ Links ]

6. Abrahams N, Jewkes R, Martin L, et al. Mortality of women from intimate partner violence in South Africa: A national epidemiological study. Violence Victims 2009;24(4):546-556. DOI:10.1891/0886-6708.24.4.546 [ Links ]

7. Fox AM, Jackson SS, Hansen NB, et al. In their own voices: A qualitative study of women's risk for intimate partner violence and HIV in South Africa. Violence against Women 2007;13(6):583-602. DOI:10.1177/1077801207299209 [ Links ]

8. Shamu S, Abrahams N, Temmerman M, et al. 'That pregnancy can bring noise into the family': Exploring intimate partner sexual violence during pregnancy in the context of HIV in Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE 2012;7(8):e43148. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0043148 [ Links ]

9. Martin LJ, Artz L. The health care practitioner's role in the management of violence against women in South Africa. CME 2006;24(2):72-76. [ Links ]

10. World Health Organization. Understanding and Addressing Violence against Women. Geneva: WHO, 2012. [ Links ]

11. World Health Organization/London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Preventing Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence against Women: Taking Action and Generating Evidence. Geneva: WHO, 2010. [ Links ]

12. Richardson J, Coid J, Petruckevitch A, Wai S, Moorey S, Feder G. Identifying domestic violence: A cross sectional study in primary care. BMJ 2002:324(7332):274-277. DOI:10.1136/bmj.324.7332.274 [ Links ]

13. Rhodes NR, Baranoff-McKenzie E. Why do battered women stay? Three decades of research. Aggress Violent Behav 1998;3(4):391-406. DOI:10.1016/s1359-1789(97)00025-6 [ Links ]

14. South African Police Service. Domestic Violence. http://www.saps.gov.za/resource_centre/women_children/domestic_violence.php (accessed 3 August 2015). [ Links ]

15. Lopes C. Intimate partner violence: A helpful guide to legal and psychosocial support services. S Afr Med J 2016;106(10):966-968. DOI:10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i10.11409 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

C Gordon

c.gordon@uct.ac.za