Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.106 no.10 Pretoria oct. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2016.v106i10.11435

IZINDABA

Election politics ride roughshod over clinicians, patients

'In individuals, insanity is rare; but in groups, parties, nations and epochs, it is the rule' (Friedrich Nietzsche)

Strange things happen at election time. Patient care and doctor support can come a very poor second to tub-thumping and vote-collecting - that's if the stories of two hospital CEOs with impeccable and impressive track records, highly respected among their rural peers, can be believed. Weird as it may seem, this year's Rural Doctors of South Africa (RuDASA) Lifetime Achiever Award recipient Dr Victor Fredlund, age 60, CEO of Mseleni Hospital, spent nearly 4 months at home on officially enforced leave (until this July). Aspirant local political candidates and unions led a charge against his withdrawal of job offers from two cleaners and his firing of a third. Head office bureaucrats insisted that the removal of the veteran stalwart from the far northern KwaZulu-Natal (KZN) hospital was 'for his own safety', bickering, fudging and stalling way after any perceived threat to him had evaporated. Then, seemingly at a loss over how to justify his lengthy absence, they charged him in August - for doing exactly what they'd advised him to do.

It got every bit as bizarre for Dr Roger Walsh, CEO at Fort England Psychiatric Hospital in Grahamstown, and his senior clinical staff, culminating in Walsh being ordered by Eastern Cape Health Department superintendent-general Dr Thobile Mben-gashe to repair to the provincial headquarters during a wildcat strike in mid-July - also for his own 'safety'. Walsh refused, citing a Bisho-ordered independent legal probe that had wholly cleared him and his management of 36 fatuous union charges involving alleged wrongdoing, mismanagement, negligence and corruption. The probe, which found local shop stewards ignorant of the terms and conditions of employment and 'in need of training', was ignored by Bisho head office, which also reneged on an earlier promise to secure a court interdict against the illegal mid-July wildcat strike. Members of the three unions had barged into wards, blowing whistles and beating sticks on tables and countertops, ordering workers out, allegedly threatening to burn their homes and at one stage allegedly assaulting Walsh. On 18 July, the strikers reportedly stole keys to the kitchen and for the food delivery van. Thinly spread senior clinicians comforted and tended to upset patients, administered medicines, cooked food and ordered sandwiches.

Fort England houses 300 patients with mental health disorders, some of them 'extremely disturbed and needing constant supervision', plus 26 prisoners and some of the 'most difficult and dangerous' state patients in the country. Walsh's team warned Bisho that 'without proper supervision there is a danger of violence, escapes and relapsing of psychosis going unnoticed'.

Back in KZN, Mseleni Hospital's Fredlund said of his union saga: 'It's just bizarre. The province's charge is that I wilfully and deliberately abused my power in dismissing a guy who failed to declare a previous assault conviction in his job application and that I withdrew the job applications of two others who allegedly falsified their addresses. That's precisely what head office advised me to do.' He was speaking just hours after his disciplinary hearing ended on 10 August. Nearly a month later, he received an email clearing him of all charges. By then he had unilaterally instructed 20 head office-suspended general orderlies and his five pivotal managers to return to work, but received instructions that he must charge his chief matron, the human resources manager and the systems manager - for allegedly illegally hiring some orderlies.

One of two local political ward aspirants allegedly called for the hospital to be torched at a rowdy public meeting where Fredland and his management were publicly accused of taking back-handers and being corrupt in making appointments.

As at Fort England, where his clinical colleague Walsh was hand-picked by the 'union-proof' (and thus short-lived) former superintendent-general, Dr Siva Pillay, to sort out and improve services at the strife-torn hospital complex, local political conditions were ripe for the picking. The 20 Mseleni District Hospital general orderly positions came up for grabs earlier this year. There were 2 720 applicants. Poverty and joblessness are endemic in the coastal bushland district, 60 km from Mozambique and close to the sprawling Lake Sibayi. Locals catch fish and grow crops to survive and, unsurprisingly, believe that any local jobs should be for local folk, a belief reinforced by politicians at local rallies. When it emerged that two of the Mseleni Hospital job applicants were not locals and had allegedly falsified their addresses, it was quick and easy to breathe the tinder into conflagration. One of two local political ward aspirants allegedly called for the hospital to be torched at a rowdy public meeting where Fredlund and his management were publicly accused of taking back-handers and being corrupt in making appointments. The meeting was held in a community hall Fredlund had built. A long list of historical grievances was produced. Two political candidates (initially both ANC) vied to outdo each other and demanded the heads of Fredlund, the hospital matron, the human resources officer and the systems manager (all were put on enforced leave by head office).

Keeping a stiff (and hairy) upper lip

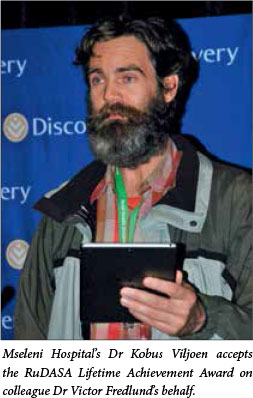

Fredlund and his colleagues made medical history by describing what is now known as Mseleni hip disease, a uniquely localised condition for which they regularly conduct surgery. No such operation happened for 4 months this year as Fredlund - a devout Christian, who displays no noticeable rancour - champed at the bit at home. His medical manager, Dr Kobus Viljoen, who stood in as CEO, has the required expertise, but was tied up running the hospital and unavailable to do surgery. Viljoen wore his sentiments about the treatment of his senior colleague on his face in the form of a full beard - he stopped shaving in protest on 3 March, the day he took over as acting CEO, removing it when Fredlund was cleared. Among the many anomalies in the saga: the provincial labour relations handbook stipulates a maximum 60-day period of suspension without charge. Fredlund was kept at home for nearly twice this long without charge. Anaesthetic machines used to gauge the hospital's oxygen supply system stood unserviced for months, putting patients in potential danger and at one stage almost forcing the transferral of 40 maternity ward patients to another hospital. A provincial special investigations unit's lengthy probe into Fredlund (encouraged by him) was kept under wraps, in spite of repeated demands that it to be made public. The provincial health department was represented by a lawyer at Fredlund's hearing in alleged contravention of its own disciplinary code.

Resignations

Even Fredlund's long-suffering, seemingly phlegmatic response had its limits. He was ready to appeal to the labour court if necessary. 'My real frustration is that this is distracting from the battle of fighting disease and poverty. If you're looking for a battle, there are plenty of things out there to fight, not each other,' he observed wryly. He declines to even try to quantify any real patient harm caused by his and his senior clinical and administrative colleagues' lengthy enforced absences. However, Izindaba learnt that at least 19 staff members resigned, including his entire HR department, with none of their functions restored. Adds Fredlund: 'I run quite a [proficient] clinical team, and I'm not indispensable. There just wasn't that much senior cover in my absence. I cannot say how many patients died or not because I wasn't there, but one friend of mine, a local pastor (and patient), died while I was away. My medical staff did a fantastic job in my absence under extreme pressure and abuse. Obviously our system was working very well, so it had degrees of buffering. A lot of people stood in and did a great job. But instead of rising to the occasion, they were trying to save a sinking ship. We were on the rise.' Mseleni Hospital won the national Batho Pele service delivery award (across all government departments) last November. The year before that it won the KZN Premier's service excellence award and the year before that the MEC (for KZN Health) service excellence award. 'Then the [provincial] DoH takes our management apart and plants an atom bomb,' Fredland observes.

The veteran hospital chief refuses to see the dark side. A friend and confidant to local chiefs and community leaders, he says some good has come of the madness. 'I've been seen to be vulnerable by the community -so many have come to express love and concern. Young and old stop me on the roadside and ask if they can come to my house and pray.' The local chief intervened very effectively at one stage to berate rowdy agitators, threatening to banish them from the district if they continued to 'act like children'. Last month the chief invited Fredlund and his wife over for supper, where they prayed for them. Fredlund's wife, Rachel, had facilitated the building of a direly needed orphanage near the hospital, tragically burnt down (due to an electrical fault) in June last year, with one child fatality. The 55 orphans were farmed out to other institutions across the country, but plans for rebuilding have stalled as the Department of Social Development struggles to come to terms with new building regulations and to approve a new plan. Meanwhile, Rachel Fredlund has already raised ZAR2 million of the 3 million needed for its reconstruction.

The similar political deconstruction of a much-improved provincial healthcare facility was still playing out at Fort England at the time of writing. Walsh and his physician wife Michelle were known and loved in the Barkley East District, where they selflessly ran the local district hospital for many years before his October 2012 appointment. The change saw him encounter some initial tension over nurses' scope of practice and a 1-day strike, to which he responded with the 'no-work, no-pay' rule. Under orders to reduce costs, he further raised the ire of the unions when he swapped seven cleaners from better-paid Sunday shifts to Monday ones where only two were on shift. He also made cleaners work a 5-day instead of a 4-day week. The measures immediately improved his hospital's national core standards cleanliness scorecard. However, there was a price. His shop stewards refused to re-engage until he was removed as CEO. Mindful of the union-linked fates of Dr Kobus Coetzer, the CEO removed from Livingstone Hospital in Port Elizabeth (under similar circumstances) and Dr Nthombi Qangule, Dora Nginza Hospital's CEO in East London, banished to health department headquarters in Bisho,[1] Walsh resolved to stay put, resisting repeated senior officials 'suggestions' that he be redeployed to Bisho.

Fredlund observes wryly: 'My real frustration is that this is distracting from the battle of fighting disease and poverty. If you're looking for a battle, there are plenty of things out there to fight, not each other'

Walsh's courage saw his entire senior clinical staff close ranks behind him - and led to the three unions (the National Education, Health and Allied Workers' Union (NEHAWU), the Democratic Nursing Organisation of South Africa (DENOSA) and the National Union of Public Service and Allied Workers (NUPSAW)) upping the ante. Finally, an advocate was hired to do a probe, taking 90 days to produce a report which was sent to head office on 15 July this year. No fault was found with Walsh or his management. The unions, unhappy with its contents, threatened to 'bring the hospital to a standstill' and wrote that they would 'forcefully remove' Walsh and his 'poor' management team. The hospital leadership met with head office officials, urging them not to give in to 'intimidation, threats and hooliganism'. Walsh's appeal to health MEC Phumzile Dyanti to secure a court interdict against the disruptive unions led to her questioning his physical safety before purportedly agreeing to the interdict. Instead of the interdict, however, the province's senior manager for tertiary hospitals arrived at his house on the evening of 18 July, saying Mbengashe had 'conceded to the unions' and that Walsh 'must move to Bisho'. (Mbengashe's predecessor, Dr Siva Pillay, considered a maverick by Bisho's political elite, had by then long been worked out.[2]) Walsh took legal advice and was told that the 'move to Bisho' instruction was both unreasonable and unlawful. He asked for written instruction, which Mbengashe duly supplied on 25 July, alleging that Walsh's removal was in the best interest of patients, continued service delivery and his own safety. In the letter, Mbengashe ordered Walsh not to report at Fort England until 5 August. Says Walsh: 'When I went back to work the unions wanted to know what I was still doing there.' He took the most pragmatic option - a holiday with his wife in Namibia until 26 August. Upon his return Mbengashe reinstituted the probe, which included fresh allegations against him. Walsh underwent a 4-hour grilling, with Mbengashe again ordering him to stay away from the hospital because 'I cannot afford any industrial action at this time.'

Doctor bodies, provinces respond

Dr Desmond Kegakilwe, Chairperson of RuDASA, said that Walsh and Fredlund were clearly dedicated, vocation-driven doctors who helped develop healthcare delivery systems independently of political dispensations or changes. 'These are not the first such cases. No matter how good and dedicated you are, you will always end up the victim if corruption comes in and you are the obstacle to whatever agenda these corrupt individuals have. Political power is used to give out this and do that and nepotism comes in. As an organisation we will fight tooth and nail against this. We must optimise service delivery - you can't sacrifice it on the altar of individual agendas, however powerful the people are. Our objective is quality rural healthcare. We're going to be watching these and similar cases very carefully in future.'

A spokesman for the KZN Department of Health, Sam Mkhwanazi, e-mailed a detailed list of questions, responded: 'There are ongoing disciplinary matters involving a number of officials from Mseleni Hospital. However, it is not the practice of the department to ventilate in the public [sic] internal and confidential matters which are employer employee-related.'

The chairperson of the South African Medical Association (SAMA), Dr Mzukisi Grootboom, said 'It boggles the mind that somebody [referring to Fredlund] would get such accolades from the very department which, when he most needed them, decided to turn a blind eye for political expediency' SAMA was 'extremely perturbed' at the treatment meted out to doctors who had dedicated most of their lives to servicing needy outlying communities, especially in the context of a country with a dire shortage of rural doctors and basic healthcare services. Demanding that they be fully reinstated until transparent probes were completed, Grootboom said SAMA would not rest until proper processes were followed.

The Eastern Cape health department failed to respond to SMSs, voice messages or e-mails.

Chris Bateman

REFERENCE

1. Bateman C. PE hospital turmoil: CEO leaves, nurses snore in patient beds. S Afr Med J 2016;106(4):320. DOI:10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i4.10763 [ Links ]

2. Bateman C. E-Cape's corruption busting chief finally ousted. S Afr Med J 2013;103(4):215-217. DOI:10.7196/SAMJ.2013.v103i4.11435. DOI:10.7196/6862 [ Links ]