Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.106 n.9 Pretoria Sep. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2016.v106i9.10568

RESEARCH

What are the communication skills and needs of doctors when communicating a poor prognosis to patients and their families? A qualitative study from South Africa

L L GancaI; L GwytherII; R HardingIII; M MeiringIV

IDip Sec Ed, BSocSc (SW) Hons, MSc (Pall Med), PGDip (HPE); Palliative Medicine, School of Public Health and Family Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIMB ChB, FCFP, MSc (Pall Med); Palliative Medicine, School of Public Health and Family Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIIBSc Hons, PhD; Cicely Saunders Institute of Palliative Care, Policy & Rehabilitation, Faculty of Life Sciences & Medicine, King's College London, UK

IVMB ChB, FCPaeds, MMed (Paed) Palliative Medicine, School of Public Health and Family Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Thousands of South Africans are diagnosed with life-threatening illness every year. Research shows that, globally, of the 20 million people who need palliative care at the end of life every year, <10% receive it.

OBJECTIVES: To explore communication skills and practices of medical practitioners when conveying a poor prognosis to patients and families, and to identify their communication skills, needs and understanding of palliative care.

METHODS: This was an exploratory qualitative study of practising doctors, using a grounded theory approach. The study was conducted at a government-funded public hospital in Cape Town, South Africa, which is a referral centre for various illnesses, including cancer. Face-to-face, one-on-one interviews using a semistructured interview guide were conducted, using audio recording.

RESULTS: The emerging theory from this study is that doctors who understand the principles of palliative care and who have an established working relationship with a palliative care team feel supported and express low levels of emotional anxiety when conveying a poor prognosis.

CONCLUSION: Having hospital-based palliative care teams in all public hospitals will provide support for patients and doctors handling difficult conversations. All healthcare professionals should be trained in palliative care so that they can effectively communicate concerns related to poor prognosis with patients and their families. Communication, loss and grief issues should be part of the curriculum in all disciplines and throughout training in medical school.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines palliative care as 'an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing problems associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial and spiritual'.[1]

Palliative care is appropriate for illnesses such as cancer, HIV/AIDS, and heart and neurodegenerative diseases. Early referral at diagnosis to a palliative care service improves patient outcomes and saves costs.[2] In order to enable clinicians to focus on treatment and manage medical complications, critical clinical time points (triggers) need to be identified to draw in the palliative care team.[3]

In 2014, the Global Atlas of Palliative Care[4] reported that of the 20 million people who need palliative care at the end of life every year, <10% receive it. Although most care is delivered in high-income countries, 80% of people who need palliative care are in low- and middle-income countries.[5] Thousands of South Africans are diagnosed with life-threatening illness every year, but there is no clear referral process to ensure access to palliative care.

Although communication skills are essential to enable doctors to break bad news, assess patient and family needs, elicit preferences and establish realistic goals of care, little research has been conducted on this topic in low- and middle-income countries.

Objectives

To explore medical doctors' use of communication skills, identify their needs to improve communication when conveying a poor prognosis, and determine their understanding of palliative care.

Methods

Study design

This was an exploratory, qualitative study using a grounded theory approach.

Study setting

This study was conducted at a tertiary hospital in the Western Cape Province, South Africa (SA). It is a referral centre for patients with various illnesses, including cancer, from community level, across the country and beyond.

Study participants and recruitment

Inclusion criteria were that participants had to be practising medical doctors fluent in English working in oncology, internal medicine, medical emergency or neurosurgery. After the study had been introduced and permission granted by heads of departments, prospective participants contacted the researcher. The study was reviewed and approved by the University of Cape Town's Faculty of Health Sciences Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC ref.: 362/2010) and the Western Cape Provincial Department of Health (LGa/LGw 20/05/11).

Data collection

A semistructured interview guide for individual in-depth interviews was developed. The audiotaped interview was transcribed verbatim.

The semistructured topic guide addressed the following areas: doctors' feelings, actions and use of communication skills when conveying a poor prognosis, the practice of introducing palliative care, managing communication in culturally diverse patient populations, managing requests for unrealistic curative intervention, and professional self-care.

Data analysis

Immersion in data from the onset of data collection and the iterative process of the grounded theory approach were observed throughout the study. Initial identification of data through coding was conducted and then data were grouped into categories. Central themes and emergent subthemes were identified and were verified by a second researcher to ensure validity. Within agreed coding, both confirmatory and deviant cases were sought.

Results

Sample characteristics

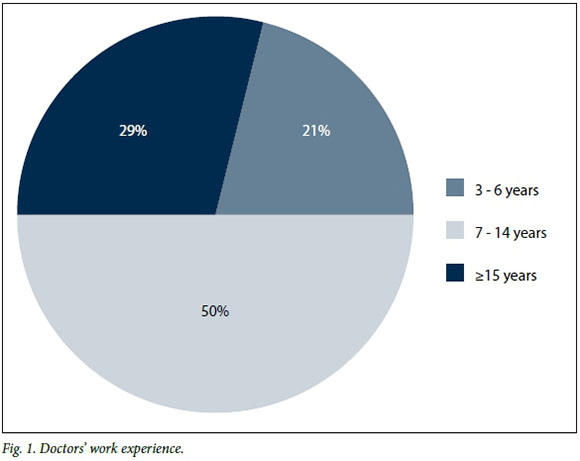

Saturation (i.e. no new themes emerged) was reached at 14 respondents, who worked in oncology, internal medicine, medical emergency and neurosurgery. Half were female, and half had been practising for between 7 and 14 years (minimum 3 years) (Fig. 1).

Findings

The full coding frame is shown in Fig. 2.

Given the breadth of findings, we report here on medical doctors' perspective on the use of communication skills with regard to breaking bad news, as this is the first stage in the introduction of palliative and end-of-life care.

Being the conveyer of a poor prognosis

All participants identified conveying a poor prognosis to patients and their families as a difficult position to be in, especially in the context of a prior clinical relationship.

'It's not easy for us to break bad news; it's very hard for us to break bad news, particularly if you formed a relationship with a patient.' (Interview 1)

Other challenging factors included when patients are children and young people, when patient and family expectations are unrealistic, when doctors lack knowledge of patient/family expectations, and when the doctor lacks formal training in counselling skills. These challenges sometimes become an emotional burden on doctors.

'We are not superhuman beings. Even if we are doctors, when people die there's something that happens to you.' (Interview 7)

Current communication practices to convey a poor prognosis

Most participants would be aware of a planned consultation, with the exception of medical emergency staff. Understanding of the following skills was recognised among all participants:

Preparation required. Prior knowledge of the patient and family

is important in planning appropriate communication.

'So I think you have to give them the facts, but in a kind way. Beating around the bush confuses people and it cheats them of the time [they] have left. You know, it's different from person to person. I tend to know all the patients by the time I have to do that so I usually judge from their personality distinctively how I am going to do it.' (Interview 3)

An emergency unit medical doctor stated that preparation for imminent death requires organisation of urgent supportive team members.

'And then we would explain that if they need time, for instance to call in other family members to say their final goodbyes or to call in their religious advisor maybe for final rights, we give them that chance where possible to bring them in and have their goodbyes, their final rituals before we switch off the ventilator.' (Interview 8)

Containment and attending. Bringing in other multidisciplinary members to meet non-medical needs:

'The benefit that we have is that we have social workers, Comacare team, within our unit. A lot of the social aspects of the families, dealing with the bad news and overcoming it is left to the Comacare and the social workers, because doctors are engrossed in taking care of the medical needs of the patients.' (Interview 14)

Inclusivity. At no stage in the patient's disease trajectory should patients be excluded from knowledge and making informed decisions about their illness.

'Patients can understand what is facing them. You owe them the right to sort out their life in the time that they have got left. You can't change that, there is no point in pretending that the person is not going to die. But how you say it, you don't have to use the words, "You are going to die," you know. You can say that "You are going to be living with this illness from now onwards, it's never going to go away."' (Interview 3)

Empathy. Recommendations were made that medical doctors should be mindful to constantly engage, consult and include patients and families in discussions or conversations held.

'... and that's where the empathy now comes to place. And that's when you know, you don't become a doctor anymore, you are a human being and you are starting to feel what this man is feeling.' (Interview 7)

Information giving and sharing. 'Information is power' - a phrase used by some participants to emphasise the importance of giving patients and families relevant and accurate information.

'When people are informed they are more content, whether it's bad news or good news, and people want to know, they don't want to be kept in the dark.' (Interview 10)

Anticipation and prevention. Doctors should ensure that support systems for the patient and family are in place during discussions and afterwards, as irrational responses and decisions can be taken when experiencing strong and painful emotions.

'However, my experience is that if you are truthful for the patients, they will be depressed for a while. Again, if they are given social support within that period, they find themselves on their feet, life goes on. I think as you use it, you become skilled at breaking bad news and patients will eventually get over whatever depression they are thrown into as long as there's a strong support structure around.' (Interview 14)

Introducing palliative care and understanding of the palliative care principles

Responses on the theme of knowledge and understanding varied and could be placed into three categories:

1. Medical practitioners who had good, clear knowledge and understanding of palliative care:

'I always give them some option or other you know, because to just say, "There is nothing we can do for you" sounds very negative.' (Interview 3)

2. Those who identified gaps in their individual knowledge and understanding of palliative care:

'I've heard of hospice but I've had no experience in seeing them active. My perception of hospice is holistic care, helping families deal with the terminal illness in the home setting.' (Interview 14)

3. Those who had little knowledge and understanding of palliative care:

'There's nothing that you can do for them and you just continue to tell them that they've got this disease, there's nothing you can do to cure it. You tell this to the family as well.' (Interview 5)

Explaining palliative or hospice care. Various responses were given by medical doctors on how they explain hospice or palliative care to patients and families, demonstrating a range of understanding. 'Hospice ...? First of all they are obviously some place where the patients go. They are basically left in peace to die. They are looked after so any kind of physical problems like pain or . all these things are addressed. But also the patients are . I imagine counselled and spoken to and taken care of from that side as well.' (Interview 13)

Emotional responses evoked by a poor prognosis. The use of silence was recommended.

'I've learnt that once you've given people this news, sometimes after giving the news just keep quiet. Let them absorb it; if they need to cry give them the space to cry.' (Interview 8)

Reassurance. Transparency of communication between tertiary hospital doctors and community-based doctors promotes patient inclusivity and being in control.

'I always write, please do not hesitate to contact me if you have any further queries. I say to the patient, "Look here, if there's a problem, your doctor will phone and ask." Then they are happy.' (Interview 10)

Continuity of care. Patients and families should have access to the primary care team to alleviate fear and ensure non-abandonment. 'If you feel we can do something more than what hospice can do for you, phone and come and we will see you. That sort of works in accommodating their concerns, as that is their biggest fear. The fear of going to hospice means you are going to stop taking care of them. Obviously it's a public perception that is still very much out there.' (Interview 6)

Handling cultural and linguistic diversity

Carefully considering and integrating cultural diversity in the care plan of specific individuals will ensure culturally sensitive and tailor-made patient care.

'So you have to really figure out totally different social, religious, cultural or ethnic background issues, for each patient. Someone needs to talk to the patient about it; not every doctor can do that and not every doctor wants to allocate time to it. I don't think it's as much a time factor than it being a personality factor. You find the time if you really want to do it.' (Interview 9)

Diversity in professional healthcare teams. To enable effective communication between healthcare team members, patients and families, the need to have diverse professional teams was highlighted. 'I think because we deal with [a] diverse population, we need diversity in our social workers. That is important, because only then do people feel comfortable. And we need cultural sensitivity and understanding amongst the caregivers, the doctors, the social workers, the staff.' (Interview 6)

Language. To augment communication between diverse cultures, use of interpreters, non-verbal gestures and drawings was recommended, and communicating with patients and their families in their first language should always be given priority.

'Because SA has lots of cultures, SA has got lots of people with different languages. One should use simple language and consciously avoid using medical jargon to explain terms or process.' (Interview 7)

Patients and families seeking a second opinion

All participants agreed that patients and families should be allowed to make preferred choices in relation to treatment options.

Choices. Medical doctors should avoid making patients and families feel guilty or bad for suggesting a desire to seek a second opinion.

'Now they are reluctant to tell you because it's supposed to be opposition. I say, tell me so that if I do any blood test I can send him the copy. When he is back, please go and see him, you don't have to follow up with me. Once they don't feel they have to hide the fact that you are not really who they want to see, they will be honest with you and it makes my life easier.' (Interview 6)

Pursuit of futile treatments.

'What does worry me about some patients is when they have been told that the time has come for palliation, that their disease could run a long course, that they would waste the time they have left even though they do know that the time is limited, they spend their whole life on the internet looking for miracle cures. You have to make peace at some time that you are going to die, and do all the things that you need to do.' (Interview 3)

Care for the professional caregiver (medical doctor)

Outlets. ICARES was mentioned.

'Two years ago I was very angry with patients. I had a very short fuse with patients because all those kind of things confounding, and then I went to ICARES, the psychologists.' (Interview 2)

Debrief. Responding to a question on how they as medical doctors cope:

'I know they are going to die and it's very difficult for us and we don't have anyone to talk to' (Interview 1)

'So the thing is, unfortunately, it's your most junior doctors who are just new in the field themselves, don't have a lot of experience, don't know where to put boundaries, you then have this ongoing cycle. And people become disillusioned, and as they become disillusioned I think they become less effective and just more withdrawn' (Interview 10)

Balance.

'What I am gonna say, our job is difficult and we know that. But it pays off at the end, we are saving lives and we're making a difference in people's lives, so it pays off in the end.' (Interview 12)

Role of palliative care

Participants shared similar views on how various stakeholders would benefit from knowledge, understanding and implementation of palliative care principles.

'I think a palliative care team will be also cost efficient from a society point of view. I mean we'll benefit emotionally but I think it will also be cheaper because if the community health workers go twice a day to help the patient rather than having him in hospital ... it's ZAR3 000 a day in hospital, the community health worker would not be costing so much. And the patient still feels better ... "I would like to be at home." So you see it is also financially a viable model, I think.' (Interview 9)

Identified needs

'But I think it could be great if there were more support networks for palliative care patients, because really, at the moment it's just hospice and the hospital. And once the patients are out there, nobody knows about cancer in the community, really they don't. From nurses to doctors to anybody, there's nobody who really can say, I know what to do with this patient when they are being palliated. They don't know how to provide morphine -adequate doses - treat constipation and prevent constipation. That to me is so sad and I would like to see through the family medicine department people being comfortable with palliation.' (Interview 3)

Recommendation for training

'I think there are many doctors who haven't gone through the process I went through. They are not that clear about dying, they have a lot of fears themselves about dying and they don't address it with their patients. So if you are very scared of dying and don't want to address it for yourself, it's difficult to address it for your patient. I think in medical schools you need case-based training on real issues of dealing with death, cultural environments and thinking about your own death. I think that has to change at the university level.' (Interview 9)

Emerging theory

Doctors who demonstrate understanding and use of the palliative care approach in their practice had, in addition, an existing working relationship with either a palliative care doctor or team. This collaboration assisted doctors to introduce confidently palliative care as an available resource, and a support system for ongoing care of the patient and family.

Theory that emerged from this study is that doctors who understand the principles of palliative care and who have an established working relationship with a palliative care team feel supported and express lower levels of emotional anxiety when conveying a poor prognosis.

Discussion

Participants highlighted that when conveying a poor prognosis, patients and families need practical information that includes addressing uncertainties about the future, available resources, experiencing death, deteriorating health and losing one's dignity.

Communication, pain management, loss and grief issues should be part of the curriculum across disciplines and throughout training in medical school. All healthcare professionals should be trained in palliative care so as to effectively communicate with patients and their families.

Support networks are needed for staff conducting this difficult task. Having hospital-based palliative care teams in all public hospitals will provide support for patients and doctors in handling difficult conversations.

Study limitations and strengths

We noted that the sample was from one setting and that the specific experience of communication may vary according to both organisational and human cultural settings.

There was indirect benefit for some of the participants of the study. Two of the participants at the end of the interview expressed surprise that they had benefited from just talking about their experiences, which they did not expect.

Conclusion

Good communication skills are not only important for better patient outcomes, but for improved professional competence and wellbeing.

The education and practice needs demonstrated in this study highlight the actions needed to meet the requirements of the World Health Assembly 2014 resolution[6] to integrate palliative care into the public health sector.

Acknowledgements. The corresponding author would like to thank Hospice Palliative Care Association for funding. Thanks are also due to Dr Liz Gwyther, Ms Phyllis Orner, doctors who participated in this study and their heads of departments, colleagues, friends, relatives and children for their unwavering support and insights.

References

1. Sepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A. Palliative care: The World Health Organization's global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage 2002;24(2):91-96. http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (accessed 4 February 2015). [ Links ]

2. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363(8):733-742. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1000678 [ Links ]

3. Yoong J, Park ER, Greer JA, et al. Early palliative care in advanced lung cancer: A qualitative study. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173(4):283-290. DOI:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1874 [ Links ]

4. Alliance, Worldwide Palliative Care, and World Health Organization. Global Atlas of Palliative Care at the End of Life. Geneva: WHO, 2014. [ Links ]

5. Harding R, Higginson IJ. Inclusion of end-of-life care in the global health agenda. Lancet Glob Health 2014;2(7):e375-e376. DOI:10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70194-9 [ Links ]

6. Gwyther L; Hospice Palliative Care Association. Breaking news: Palliative care resolution adopted at WHA. 25 May 2014. www.ehospice.com/southafrica/Default/tabid/10689/ArticleId/10620 (accessed 4 February 2015). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

L Ganca

linda.ganca@uct.ac.za

Accepted 31 January 2016.