Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.106 n.6 Pretoria Jun. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2016.v106i6.10255

IN PRACTICE

HEALTHCARE DELIVERY

Complex adaptive HIV/AIDS risk reduction: Plausible implications from findings in Limpopo Province, South Africa

C J BurmanI; M A AphaneII

IPhD ; The Rural Development and Innovation Hub, University of Limpopo, Polokwane, South Africa

IIM Development; The Rural Development and Innovation Hub, University of Limpopo, Polokwane, South Africa

ABSTRACT

This article emphasises that when working with complex adaptive systems it is possible to stimulate new social practices and/or cognitive perspectives that contribute to risk reduction, associated with reducing aggregate community viral loads. The process of achieving this is highly participatory and is methodologically possible because evidence of 'attractors' that influence the social practices can be identified using qualitative research techniques. Using findings from Limpopo Province, South Africa, we argue that working with 'wellness attractors' and increasing their presence within the HIV/AIDS landscape could influence aggregate community viral loads. While the analysis that is presented is unconventional, it is plausible that this perspective may hold potential to develop a biosocial response - which the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) has called for - that reinforces the biomedical opportunities that are now available to achieve the ambition of ending AIDS by 2030.

We introduce an innovative intervention in Limpopo Province, South Africa (SA) that was designed to respond to complex aspects of the HIV/AIDS landscape. The embryonic findings suggest that this style of intervention may be a step towards developing a contribution to the biosocial response to the epidemic that the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS) has called for in the context of ending AIDS by 2030. The reflection is structured in the following way: we explain how we incorporated complex adaptive systems into the intervention design, followed by a brief overview of the findings. In the discussion we highlight the possibility that something similar may have happened in Zimbabwe, from 1997 to 2007, and then discuss the plausible ramifications of this type of intervention in the context of 2030.

The focus of the partnership

The partnership is between an HIV/AIDS-focused community-based organisation called the Waterberg Welfare Society (WWS) and the University of Limpopo. The primary focus of the partnership was to respond to frustrations identified by WWS about the effectiveness of the tools and techniques that were at their disposal to promote wellness within the communities they work with. The partnership became influenced by Vision 90-90-90 and the claim by UNAIDS that 'business as usual' is unlikely to achieve the end of AIDS by 2030.[1] It was also influenced by the UNAIDS statement that 'we need to develop a biosocial response' to reinforce the biomedical opportunities that are now available to achieve the 2030 ambition.

From this platform, the objective of the partnership developed into reducing the aggregate community viral load by developing biosocial tools and techniques to reinforce the biomedical opportunities available to end AIDS and reduce HIV transmission opportunities.[2]

Managing complex adaptive systems

Managing a complex adaptive system requires knowledge about the basics of complexity theory and the laws associated with the functioning of complex adaptive systems. The literature on the former is colossal and the literature on the latter is equally daunting.[3] However, managing complex adaptive systems has been synthesised into more compact bundles. Managing a complex adaptive system places emphasis on working with the dynamics of the system within which the challenge is situated because the dynamics are co-constitutive parts of the challenge.

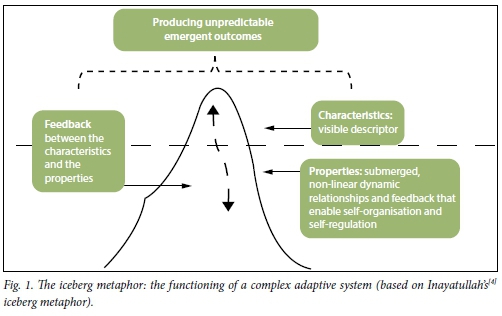

An iceberg metaphor and the dynamics of complex adaptive systems

Futures scientist, Inayatullah[4] developed an iceberg metaphor to describe the workings of complex systems. He argued that the visible aspect of the metaphor is one descriptive layer of the phenomenon that is generally represented in the name attributed to the challenge, such as 'stigma' or 'disclosure. He then argued that the submerged aspect of the metaphor represents discrete layers that influence, sustain and co-constitute the visible descriptor.[4]

In complex adaptive systems, the visible part of the iceberg represents the characteristics of the issue and the submerged aspects of the metaphor demonstrate some distinctive properties which co-constitute the visible descriptor. Feedback between - and within - all of the layers provides a dispositional, self-regulating identity to the system. The properties include: a variable number of interacting agents, with an agent being anything that influences the system; feedback mechanisms that connect and influence different agents within the system; and linear - or cause-effect - and non-linear interactions (Fig. 1).

The dispositional, self-regulating identity of complex adaptive systems reflects two issues: first, although there are multiple interactions between agents, these interactions are constrained - or restricted - within permeable boundaries; second, the agents tend to interact more with specific aspects of the complex adaptive system than with other parts. The sites within the system with which agents most commonly interact are called 'attractor sites'. In social systems, the interactions with specific attractor sites 'are reflected in patterns of behaviour which are never exactly repeated but are always similar to each other',[5] such as the ebb and flow of rumour and myth associated with HIV/AIDS.[6]

Incorporating attractors into the intervention framework

From the perspective of an intervention design, attractors become critical for both methodological reasons and implementation. Methodologically, most of the functionings of a complex adaptive system are so discrete that it is impossible to identify them, let alone modify them. However, it is possible to identify attractors using qualitative research techniques which open a window of analytic opportunity.[7]

From the implementation perspective, because complex adaptive systems are unstable and adaptable, it is possible to disrupt them further, catalysing downstream ripple effects as new attractors emerge, and/or existing attractors are modified, as the agents adaptively reorganise around the disruption. During, or after, the submerged reorganisation processes, the shifts in the overall attractor landscape can be monitored and the visible social, or behavioural, emergence associated with each shift in the attractor landscape can be evaluated. Once there is clarity about which attractor/s is/are influencing preferred social practices and/or promoting cognitive perspectives that contribute to risk reduction, it is then a matter of reinforcing those attractors to expand the impact and, if possible, to simultaneously destabilise the attractors that detract from the project goal. The advantage of this approach is that the intervention is firmly rooted within the functioning of the system, rather than focusing exclusively on the visible characteristics of the system.

Method

In order to identify existing attractors and to create new ones, two catalysing influences were applied: an educational package containing up-to-date information about HIV/AIDS and enabling the participants (n=21) with the autonomy to introduce the content of the educational package into their work in ways that they thought would add value. The findings that are presented were identified using an adapted version of a qualitative research technique called causal layered analysis[7] 12 months after the educational package was introduced.[8]

Findings

Four principal wellness attractors that contributed to reducing the aggregate community viral load were identified during the intervention pilot: 'movement from HIV being perceived as a death sentence to a chronic condition', 'the viral load', 'relating new knowledge about HIV/AIDS to personal experience' and the 'origins of HIV'. Each of these wellness attractors was associated with altered social practices and/or cognitive perspectives that contribute to risk reduction, thereby reducing the aggregate community viral load (Table 1).

The first three wellness attractors have a self-evident logic to them. The fourth was a mystery to the university component of the partnership, but this was explained by WWS. The power of the 'origins' attractor, in the context that WWS works, is that it counters localised rumour and myth about the 'origins of HIV' which are factors that detract from the ambition of reducing the aggregate community viral load. (Two other pilot studies have been initiated in other parts of the province and preliminary reports indicate that the 'origins' and the 'viral load' attractors are also emerging in one of them. However, these reports are unsubstantiated at this time.)

Examining the same findings in a slightly different way suggests that a combination of wellness attractors influence the same social practices and/or cognitive perspectives that contribute to risk reduction (Table 2).

The 'origins' attractor remains a mystery from this perspective because it continues to be a source of much positive discussion at WWS, yet its influence remains ambiguous.

Discussion

Partially constrained, patterned instability that contains some non-linear interactions makes complex adaptive systems prone to emergent incremental change and innovation. For example, zoonosis happens because of the gradual coalescing of the interactions and feedback between novel agents as different systems become compressed into a complex adaptive system, giving rise to emergent possibilities that may adapt into qualitatively new phenomena - such as the emergence of HIV about a century ago.[9] Despite limited numbers, we have demonstrated that during the first pilot study it has been possible to generate emergent social practices and/or cognitive perspectives that contribute to risk reduction and identify the submerged wellness attractors that are associated with the emergence. The partnership is now in the process of reinforcing these attractors to determine if this will increase the impact of the intervention.

In the discussion that follows we will only claim abductive plausibility because we believe that further work is required to determine the effectiveness of the intervention design.

What could have happened in Limpopo?

Many ofthe WWS participants expressed frustration with the inadequacies of their existing tools and techniques to promote risk-reducing social practices. This could indicate that prior to the intervention dispositional characteristics of the system were: (i) frustration; and (ii) a desire to respond to this frustration by developing new tools to improve the impact of their work. A comprehensive educational package was delivered and the participants began the low-cost process of incorporating the new knowledge into their work. The educational package could have acted as a catalyst that produced disproportional changes - the new wellness attractors - and 12 months after the attractors were identified WWS continues to work with them because 'structure and coherence' is developing to such an extent that they believe they are the foundations of future prevention and risk-reduction tools.

Other plausible examples of complex adaptive change processes

The most striking example is the dramatic decline in HIV prevalence - in the absence of widely accessible antiretroviral medication - in Zimbabwe, from 1997 to 2007. In Table 3 an analysis that was published in 2011[10] is re-examined from the perspective of plausibility and complex adaptive systems.

It is plausible that a range of discrete feedback loops and relationships gradually altered the attractors on a significant scale in the Zimbabwean HIV landscape that enabled spaces to emerge for a shift in specific social practices and/or cognitive perspectives that contribute to risk reduction that may account for the dramatic, home-grown, biosocial decline in HIV prevalence. One thing is certain, the 2011 account was developed by high-level academics and despite deliberate attempts to identify specific rational causes of the overall decline, none was identified, which goes some way to plausibly suggest that the perspective we have presented may have the potential to be applied on a national scale.

Future attractors that are likely to influence the HIV/AIDS landscape

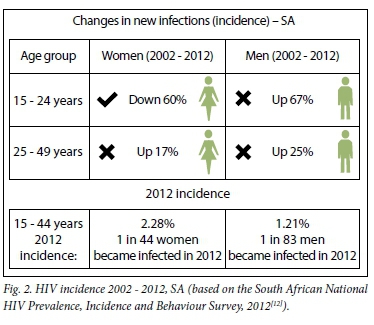

At the moment the SA track record with regard to incidence is not encouraging (Fig. 2), with the exception of prevention of mother-to-child transmission.[11]

As the impact of treatment as prevention increases, it is logical to expect this trend to radically alter. However, the downstream effect of this is likely to create instability in systems relating to individual experiences of living with HIV,[13] as well as systems designed to reduce the impact of HIV/AIDS.[14] Both of these downstream challenges represent potential Achilles' heels to the ambition to end AIDS. Some of this instability is likely to demonstrate some complex characteristics, suggesting that the more we can learn about working with complexity and HIV/AIDS now, the better we will be able to expand the biosocial armamentarium for the future.

What could the implications be for developing a biosocial response to the contemporary epidemic as a contribution to ending AIDS?

It is plausible that this style of intervention could be applied to diverse aspects of the treatment and care continuum that demonstrate complex instability. The process would include identifying instability along the continuum, catalysing the emergence of new attractors that make sense to the target groups and working with the attractors to develop and reinforce appropriate strategies to reduce the aggregate national viral load. The 'value add' in this approach is that, when there is instability that is difficult to manage using conventional mechanisms, the identification of relevant attractors and reinforcement of those attractors enables a targeted response that makes sense in different contexts because the process is hard-wired to incorporate localised characteristics of the HIV/AIDS landscape.

Despite the limitations of the pilot study in Limpopo, there has been sufficient international growth in management tools and techniques designed to work with complexity, including electronic monitoring and evaluation tools that could be aligned to SA's eHealth strategy,[15] to warrant further investigation. This would require further pilots to empirically determine if this style of intervention could contribute to developing one of the biosocial responses that UNAIDS calls for.

Conclusion

We have introduced some embryonic findings from Limpopo which suggest that working with HIV risk reduction and prevention using management techniques associated with complex adaptive systems may hold potential to open innovative biosocial spaces that could contribute to the ambition of ending AIDS by 2030. In this instance one educational package, followed by experimental efforts to apply the knowledge, catalysed the emergence of four wellness attractors that influenced biosocial factors that affect the trajectory of the epidemic. By reinforcing these attractors it is plausible that 'disproportionately major consequences' that reduce the aggregate community viral load could occur. It is also plausible that this style of intervention could contribute to developing a biosocial response, as called for by UNAIDS. The striking resemblance between the Zimbabwean and the Limpopo attractors could indicate that wellness attractors can influence the epidemic on a national scale. The emergence of HIV was enabled by complex zoonotic processes almost a century ago.[9] It is plausible that complexity can now contribute to reducing its presence in the build-up to 2030.

References

1. UNAIDS. The Gap Report. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS, 2014. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/campaigns/2014/2014gapreport/gapreport (accessed 12 May 2016). [ Links ]

2. Burman CJ, Aphane M, Mtapuri O, Delobelle P. Expanding the prevention armamentarium portfolio: A framework for promoting HIV-conversant communities within a complex, adaptive epidemiological landscape. J Social Aspects HIV/AIDS 2015;12:18-29. DOI:10.1080/17290376.2015.1034292 [ Links ]

3. Sturmberg J, Martin C. Complexity in health: An introduction. In: Sturmberg J, Martin C, eds. Handbook of Systems and Complexity in Health. New York: Springer, 2013. [ Links ]

4. Inayatullah S. Causal layered analysis. Futures 1998;30(8):815-829. DOI:10.1016/s0016-3287(98)00086-x. [ Links ]

5. Stacey R. Complexity and Group Processes: A Radical Social Understanding of Individuals. New York: Brunner-Routledge, 2003. [ Links ]

6. Dickinson D. Myths or theories? Alternative beliefs about HIV and AIDS in South African working class communities. Afr J AIDS Res 2013;12:121-130. DOI:10.2989/16085906.2013.863212 [ Links ]

7. Bishop BJ, Dzidic PL. Dealing with wicked problems: Conducting a causal layered analysis of complex social psychological issues. Am J Community Psychol 2014;53:13-24. DOI: 10.1007/s10464-013-9611-5 [ Links ]

8. Burman CJ, Aphane M. Community viral load management: Can 'attractors' contribute to developing an improved bio-social response to HIV risk-reduction? Nonlinear Dynamics Psychol Life Sci 2015;20(1):1-36. [ Links ]

9. Sharp PM, Hahn BH. Origins of HIV and the AIDS pandemic. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2011;1:a006841. DOI:10.1101/cshperspect.a006841 [ Links ]

10. Halperin DT, Mugurungi O, Hallett TB, et al. A surprising prevention success: Why did the HIV epidemic decline in Zimbabwe? PLoS Med 2011;8:e1000414. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000414 [ Links ]

11. Barker P, Barron P, Bhardwaj S, Pillay Y. The role of quality improvement in achieving effective large-scale prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in South Africa. AIDS 2015;29 (Suppl 2):S137-S143. DOI:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000718 [ Links ]

12. Burman CJ, Aphane M, Delobelle P. Reducing the overall HIV-burden in South Africa: Is 'reviving ABC' an appropriate fit for a complex, adaptive epidemiological HIV landscape? Afr J AIDS Res 2015;14:13-28. DOI:10.2989/16085906.2015.1016988 [ Links ]

13. Vella S. End of AIDS on the horizon, but innovation needed to end HIV. Lancet HIV 2015;2:e74-e5. DOI:10.1016/s2352-3018(15)00023-5 [ Links ]

14. Whiteside A, Cohen J, Strauss M. Reconciling the science and policy divide: The reality of scaling up antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. S Afr J HIV Med 2015;16:355. DOI:10.4102/hivmed.v16i1.355 [ Links ]

15. Burman CJ, Aphane M, Delobelle P. Weak signal detection: A discrete window of opportunity for achieving 'Vision 90:90:90'? SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS. 2016;13:17-34. DOI:10.1080/17290376.2015.1123642 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

C J Burman

burmanc@edupark.ac.za

Accepted 20 April 2016.