Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.106 no.4 Pretoria Abr. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2016.v106i4.10214

RESEARCH

Evaluating current knowledge of legislation and practice of obstetricians and gynaecologists in the management of fetal remains in South Africa

L du Toit-PrinslooI; C PicklesII; H LombaardIII

IMB ChB, DipForMed (SA) Path, FCForPath (SA), MMed (Path) (Forens); Department of Forensic Medicine, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

IILLB, LLM, LLD; South African Institute for Advanced Constitutional, Public, Human Rights and International Law, University of Johannesburg, South Africa

IIIMB ChB, MMed (OetG), FCOG (SA); Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, School of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: In the clinical setting, the main legislative provisions governing the management and 'disposal' of fetal remains in South Africa are the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act 92 of 1996 and the Births and Deaths Registration Act 51 of 1992

OBJECTIVES: To determine obstetricians' and gynaecologists' current knowledge of this legislation. Current practice with regard to certification of death and methods of disposal of fetal material was also reviewed

METHODS: A questionnaire-based study was conducted. The data collected included demographic details, qualifications, years of experience, working environment (public/private practice), responses to general questions reviewing knowledge of current legislation, and practical experience

RESULTS: Seventy-six questionnaires were returned, with practitioners from the private and public sectors nearly equally represented. It was found that there is a concerning gap in obstetricians' and gynaecologists' knowledge of the law, and that some practitioners are acting outside the scope of the law. The study further revealed that patients' needs are not properly accommodated under the current legislative provisions, because the law prevents certain remains from being respectfully managed

CONCLUSIONS: The study findings suggest that improved training of practitioners, together with possible law reform, are required to better serve the needs of patients

Fetal remains and the law

In South Africa (SA), several laws govern the management of fetal remains. In the clinical setting, these are mainly the Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act 92 of 1996[1] (Choice Act) and the Births and Deaths Registration Act 51 of 1992.[2] These laws result in fetal remains being assigned different status under different Acts, which leads to some would-be parents being denied choice in the method of disposal of the remains.

In the medical management of pregnant women, the woman and the fetus are sometimes seen as two patients who require medical care (in the event that the patient presents her fetus as a patient). In contrast, SA law manages the pregnant woman and the fetus as one entity.[3] The fetus therefore has no vested rights and is not protected under the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996, or under the common law unless live birth occurs.[4] The only protectable interests that the fetus has is the so-called nasciturus fiction, which states that an unborn may inherit provided it is born alive.[5] This principle has the effect of holding the unborn's interests in abeyance.[5]

The Choice Act[1] provides for the termination of pregnancy (TOP), which includes both elective TOP services in the case of early pregnancies and therapeutic TOP services in the case of later pregnancies. The Act prescribes who can perform these procedures and where they must take place. The Act defines TOP as 'the separation and expulsion, by medical or surgical means, of the contents of the uterus of a pregnant woman', but the term 'contents' is not defined.[1] 'Contents' can include fetal matter, placenta, membranes and blood removed from a woman's uterus. Once the contents have been removed, the Act prescribes that the facilities where the TOP is being carried out must have 'access to safe waste

disposal infrastructure'.[1] Furthermore, 'waste' and 'disposal' are not defined by the Act. The regulation of medical waste in SA is a complex maze of various legislative enactments and regulations. Specifically in Gauteng, according to the Gauteng Health Care Waste Management Regulations in terms of the Environment Conservation Act 73 of 1989, the definition of 'pathological waste' includes human fetuses.[6] This means that all fetal material resulting from TOP constitutes pathological waste and should be disposed of in the correct manner. This does not take into account whether the termination was elective or therapeutic. Would-be parents who lose a fetus due to TOP are therefore not being given the choice to sensitively dispose of the fetus and therefore cannot bury or cremate the remains.

There is currently no statutory definition of viability in SA. The Births and Deaths Registration Act 51 of 1992[2] only defines a stillbirth or stillborn as a fetus that 'had at least 26 weeks of intra-uterine existence but showed no signs of life after birth'. According to this Act, a burial order can only be obtained if a death notification form has been completed.[2] The latter will be issued in cases of stillbirth and when babies are born alive and then die. As a general rule of practice, death notification forms are not completed for non-viable products of conception (miscarriages/TOP), and therefore a legal burial cannot follow. These fetuses are usually disposed of as medical waste.[6] This indicates that a stillborn fetus at 26 weeks' gestational age can, in terms of the Births and Deaths Registration Act,[2] be buried, yet if the same fetus was 'born' as a result of a TOP, the body should be disposed of as medical waste - clearly assigning different status to the fetal remains.

The need for sensitive methods of disposal of fetal remains has not been addressed in SA. Internationally, this issue became a concern after the Polinghorne report,[7] which indicated that 'on the basis of its potential to develop into a human being, a fetus is entitled to respect, according it a status broadly comparable to that of a living person. In the UK, the Human Tissue Authority published 'Guidance on the disposal of pregnancy remains following pregnancy loss or termination' in March 2015.[8] In accordance with the Human Tissue Act 2004,[9] these guidelines, in relation to the disposal of fetal remains, provide that 'the particular sensitive nature of this tissue means that the wishes of the woman, and her understanding of the disposal options open to her, are of paramount importance and should be respected and acted upon.[8]

In Scotland, the National Medical Advisory Committee has published guidelines indicating that regardless of the gestational age of the fetus, the wishes of the would-be parent(s) should be adhered to when disposing of the remains.[10] Although such guidelines are in place, a 2005 study by Cameron and Penny[10] in which women were interviewed after early pregnancy loss indicated that this practice was adhered to in less than 50% of cases.

In Australia, the Ethical Standards for Catholic Health and Aged Services in Australia state that when 'embryos and fetuses die, they should be given the same respect as is due to every human being who dies' (6.14).[11] These standards also include 'to assist with the proper disposal of the body or remains in ways respectful of the dignity of human life and in keeping with the parents' wishes'.[11]

The management of fetal remains in other countries is either policy based or statutory based. Policy-based burial options are being used in the UK. The Cardiff and Vale University Health Board has a 'Policy for Management of Fetal Remains, Stillbirth and Neonatal Death' and acknowledges that the parents have a choice in the burial options regardless of the gestational age of the fetus.[12] Alberta, Canada, adopts a statutory-based approach, and the Alberta Cemeteries Act RSA 2000 CC-3[13] provides support for the burial of 'pre-viable' fetuses.[13] It should be noted that it is difficult to compare how fetal remains are managed in foreign jurisdictions because the approaches adopted are substantively different. Some countries, such as the UK, have policies,[12] others, such as Australia, have ethical guidelines,[12] while Alberta, Canada, has legislation.[13] Regardless, there are systems in place that facilitate respectful management of fetal remains. It is clear that the current SA approach towards the management of fetal remains is not sensitive enough to patients' needs and that current legislation is outdated.

Objective

To determine obstetricians' and gynaecologists' current knowledge of legislative provisions governing the management and disposal of fetal remains, and review current practice with regard to certification of death and method of disposal of fetal material.

Methods

A questionnaire-based study was conducted. Questionnaires were handed to delegates attending the Obstertrics and Gynaecology Update 2015 conference held on 7 - 9 May 2015 at the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Pretoria.

The data collected included demographic details, qualifications, years of experience, working environment (public/private practice), responses to general questions reviewing the knowledge of current legislation, and practical experience.

Approval was obtained from the Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee, University of Pretoria, before commencement of the study.

Results and discussion

A total of 76 of the 270 questionnaires distributed were handed in (response rate 28.1%). Not all clinicians/practitioners (obstetricians and gynaecologists) completed every question posed, so the denominators to the percentages that follow vary.

Demographic details

The respondents comprised 44 males (57.9%) and 32 females (42.1%). One of the 75 who provided their age (1.3%) was aged 20 -29 years, 26 (34.2%) were aged 30 - 39 years, 21 (27.6%) were aged 40 - 49 years, 14 (18.4%) were aged 50 - 59 years and 13 (17.1%) were aged >60 years. Seventeen of 74 (23.0%) were registrars (specialists in training), with the majority (57, 77.0%) being specialists. In the evaluation of the number of years qualified, the registrars were added to the group that had been qualified for 0 - 5 years. Twenty-five of 71 (35.2%) of the practitioners had been qualified for 0 - 5 years, 12 (16.9%) for 6 - 10 years, 9 (12.7%) for 11 - 15 years, 4 (5.6%) for 16 -20 years, 9 (12.7%) for 21 - 25 years, and 12 (16.9%) for >25 years. There was a fairly even distribution between the sectors in which the clinicians practised, with 30/74 (40.5%) being in private practice, 37 (49.3%) in the public sector, and 7 (9.3%) practising in both.

Performance of TOP

Forty-three of 74 clinicians (58.1%) indicated that they performed TOP, with 20 (46.5%) of these working in the public sector, 18 (41.9%) in the private sector and 5 (11.6%) in both. The respondents were asked to indicate the gestational age at which they conducted the majority of TOP procedures. Although only 43 clinicians stated that they performed TOP, 59 responded to the question pertaining to the gestational age at which terminations were done. In most cases this was at a gestational age of <20 weeks. In 20 cases (33.9%) the gestational age was 0 - 13 weeks, in 22 (37.3%) 13 - 20 weeks, and in 14 (23.7%) 20 - 26 weeks. Only 3 respondents (5.1%) indicated that the majority of the pregnancy terminations they performed were at >26 weeks. Two of these clinicians worked in the private sector and one in the public sector.

Questions pertaining to legal definitions

The overwhelming majority of the respondents (66/69, 95.7%) indicated that gestational age is defined with reference to the first day of the last normal menstrual period (LNMP). Although no Act in SA law provides this definition, the Births and Deaths Registration Act[2] defines a stillbirth as birth of a fetus that completed 26 weeks of intrauterine life. The assumption is therefore that the legal definition of gestational age should be in keeping with time of intrauterine life and be indicated as from conception (generally medically regarded as 2 weeks after the first day of the LNMP). A fetus of 28 weeks' gestational age according to the first day of the LNMP has spent 26 weeks in the uterus.

According to SA law, the fetus is not regarded as a separate entity with vested rights but is seen as part of the pregnant woman.[3] The question was posed to the clinicians whether or not this statement was true. The majority of those who responded (51/70, 72.9%) agreed, but 11 (15.7%) stated that the fetus is regarded as a separate legal entity with vested rights and 8 (11.4%) were not sure.

There is currently no statutory definition of fetal viability. The term viability was defined in the repealed Births, Marriages and Deaths Registration Act 81 of 1963 as 'viable in relation to a child means that it had at least six months of intrauterine existence'. The 6 months of intrauterine existence was in keeping with 26 weeks of gestational age as in the Births and Deaths Registration Act.[2] Case law in SA provides various gestational periods for viability. In S v Mshumpa[14] 25 weeks' gestational age was accepted, yet in S v Molefe[15] 28 weeks' gestation was accepted for viability in cases of concealment of birth. Viability is affected by the level of development of a country, and it may differ between urban and rural areas. [16] The majority of the clinicians (51/75, 68.0%) stated that viability is defined in law, and 55 clinicians gave a range of 12 - 28 weeks' gestational age, 1 (1.8%) indicating 12 weeks, 23 (41.8%) 20 - 26 weeks and 31 (56.4%) 28 weeks as the gestational age at which viability is legally defined. Fifteen of 75 clinicians (20.0%) indicated correctly that viability is not legally defined, and 9 (12.0%) were unsure.

Currently undergraduate students at the University of Pretoria receive one formal lecture on the legislation regarding fetal remains in the 3rd year of study. It is not clear what is being done at other universities, or what is being taught to postgraduate students.

The Births and Deaths Registration Act 51 of 1992 defines stillbirth as birth of a fetus after at least 26 weeks of intrauterine existence, without any signs of life.'21 The majority of the respondents (57/76, 75.0%) correctly indicated that stillbirth is defined in law. An open-ended question was posed for them to write down the gestational age at which a fetus is defined as stillborn, and this varied from 12 to 28 weeks. One of 57 (1.8%) gave from 12 weeks' gestational age, 16 (28.1%) 20 - 24 weeks, 8 (14.0%) 26 weeks, 1 (1.8%) 27 weeks and the majority (31, 54.3%) 28 weeks. Five of the 76 (6.6%) wrongly stated that stillbirth is not defined in law, and 14 (18.4%) were not sure.

Early pregnancy loss

Currently only certain remains can be buried. In terms of the Births and Deaths Registration Act, [2] only a liveborn fetus that later dies and a stillborn fetus of at least 26 weeks' gestational age may legally be buried. The products of any pregnancy loss before 26 weeks' gestation are therefore considered 'early pregnancy loss' and should be considered medical waste. The clinicians were asked to indicate at what gestational age the loss of the pregnancy would be regarded as 'early pregnancy loss'. The responses varied, with gestational ages of <12 weeks up to 26 weeks, the majority (19/76, 25.0%) indicating that any pregnancy loss at <12 weeks' gestational age is an early pregnancy loss. Fifty-two of 73 clinicians (71.2%) indicated that they had been asked for the remains of the fetus by the parents after early pregnancy loss. In these cases the gestational age had ranged from <12 weeks to 26 weeks. Despite the provisions of the Births and Deaths Registration Act,[2] 31 (54.4%) of these clinicians had facilitated burial for the parents in cases of early pregnancy loss. This is in conflict with the prescribed legislation and can therefore be interpreted as being against the law. Following up on that, the clinicians were asked what authority had been used to facilitate burial in these cases. Sixteen of the 31 clinicians (51.6%) indicated hospital policy, 13 (41.9%) ethical guidelines and 1 (3.2%) legislation. No answer was provided in 1 instance (although the clinician did facilitate burial). Surprisingly, the majority of cases in which burial had been facilitated (n=19, 61.3%) occurred in the public sector, with 9 burials (29.0%) facilitated by clinicians in the private sector and 3 (9.7%) by clinicians working in both sectors. It should be noted that there are no hospital policies or ethical guidelines that permit the facilitation of burial of fetal remains after early pregnancy loss. These fetuses were therefore illegally buried.

Management of fetal remains

A table was provided reviewing how fetal remains emanating from miscarriage, TOP and early gestational age live birth were managed. The options included whether or not burial should be facilitated, if the remains should be incinerated (managed as medical waste), or if the clinician was unsure. It should be noted that some respondents marked both burial and incineration, which can be interpreted as that the decision would have depended on the parents' wishes.

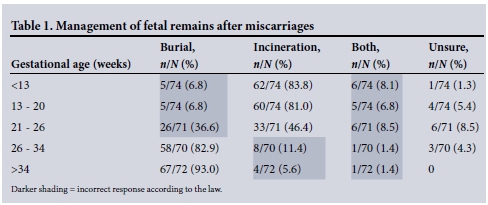

Management of fetal remains stemming from miscarriages

As stated above, a death notification can only be completed in cases of live birth, and if a baby is stillborn after 26 weeks, the remains should be buried in terms of the Births and Deaths Registration Act.[2] If viability is defined as a gestational age of 26 weeks, the products of all spontaneous losses of pregnancy (miscarriages) before 26 weeks should be managed as medical waste and be incinerated. Table 1 depicts the responses of the clinicians with regard to management of the products of miscarriages. The areas with darker shading can be interpreted as having been done wrongly according to the law.

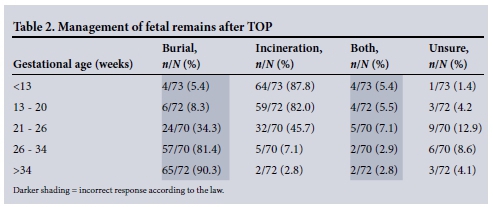

Management of fetal remains stemming from TOP

Although legislation regarding the management of medical waste varies, all fetal remains stemming from TOP should be managed as pathological/medical waste and therefore be incinerated. Table 2 sets out the clinicians' responses with regard to how they managed such remains. The areas with darker shading diverge from the current legal prescriptions.

In the UK, the Royal College of Nursing has guidelines for nurses and midwives on 'Sensitive disposal of all fetal remains'.[17] According to the guidelines, a working group conducted a survey in the UK in 2000 and found a wide variation in the management of fetal remains, although most fetal tissue from early pregnancy loss was incinerated. The guidelines state that incineration of these products of pregnancy loss 'is felt to be completely unacceptable by health professionals working within this area'.[17] In 2015, 'Guidance on the disposal of pregnancy remains following pregnancy loss or termination' drafted by the Human Tissue Authority in the UK states that incineration should only be done if the woman makes the choice to incinerate.[8]

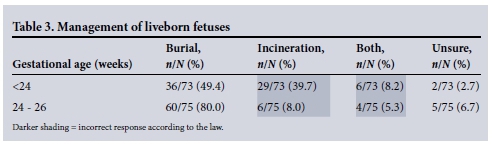

Management of liveborn fetuses

Section 9 of the Births and Deaths Registration Act stipulates that all babies born alive should be registered.[2] No gestational age is connected to the live birth. Table 3 indicates the respondents' management of liveborn fetuses at an early gestational age. It is of concern that in a number of cases they indicated incorrectly (darker shading) that incineration should be done.

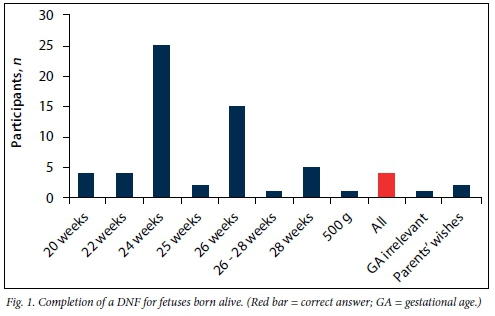

Completion of death notification forms (DNFs)

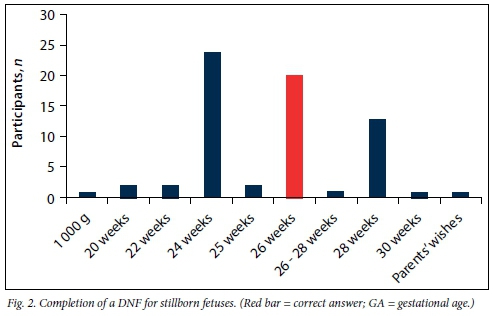

According to the Births and Deaths Registration Act,[2] all liveborn and stillborn fetuses (of at least 26 weeks' gestational age) should be registered and a DNF must be completed.[2] The participants were asked to indicate at what gestational age they would complete a DNF in cases of live birth and stillbirth. The gestational ages given ranged from 20 weeks to 28 weeks in cases of live birth (Fig. 1). Only 2 participants answered correctly (red bar). Only 20 participants indicated the correct gestational age at which a DNF should be completed in cases of stillbirth (Fig. 2, red bar).

Conclusion

This study indicates that there appears to be a lack of knowledge of the current statutory legal provisions among obstetricians and gynaecologists in SA. However, it appears that some clinicians manage fetal remains with dignity, as was encouraged by the Polinghorne report.[7] Several questions remain. Should more law be taught in the undergraduate and postgraduate medical curriculum, should clinicians be held accountable for acting outside the scope of the law, and/or should the law change in order to be in keeping with international trends? For clinicians, the question should always be 'How can we better serve the dignity of our patients who experience pregnancy loss?'

References

1. Republic of South Africa. Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act 92 of 1996. Government Gazette, 1996. http://www.gov.za/documents/choice-termination-pregnancy-amendment-act (accessed 7 March 2016). [ Links ]

2. Republic of South Africa. Births and Deaths Registration Act 51 of 1992. Government Gazette, 1992. www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/a51_1992.pdf (accessed 7 March 2016). [ Links ]

3. Pickles C. Approaches to pregnancy under the law: A relational response to the current South African position and recent academic trends. De Jure 2014;47(1):20-41. [ Links ]

4. Christian League of South Africa v. Rall 1981 2 SA 821 (O).

5. Boezaart T. Child law, the child and South African private law. In: Boezaart T, ed. Child Law in South Africa. Cape Town: Juta, 2013:5-10. [ Links ]

6. Republic of South Africa. Environment Conservation Act 73 of 1989. Government Gazette, 1989. http://www.acts.co.za/environment-conservation-act-1989/ (accessed 7 March 2016). [ Links ]

7. Polinghorne J. Review of the Guidance on the Research Use of Fetuses and Fetal Material. London: Her Majesty's Stationary Office, 1989. [ Links ]

8. Human Tissue Authority. Guidance on the disposal ofpregnancy remains following pregnancy loss or termination. https://www.hta.gov.uk/policies/hta-guidance-sensitive-handling-pregnancy-remains (accessed 26 August 2015). [ Links ]

9. United Kingdom Legislation. Human Tissue Act 2004. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2004/30/contents (accessed 7 March 2016). [ Links ]

10. Cameron MJ, Penny C. Are national recommendations regarding examination and disposal of products of miscarriage being followed? A need for revised guidelines? Hum Reprod 2005;20(2):531-535. DOI:10.1093/humrep/deh617 [ Links ]

11. Catholic Health Association of Australia. Code of Ethical Standards for Catholic Health and Aged Service in Australia. 2001. www.donatelife.gov.au/sites/.../Code%20of%20ethics-full%20copy.pdf (accessed 26 August 2015). [ Links ]

12. Cardiff and Vale University Health Board. Policy for Management of Fetal Remains, Stillbirth and Neonatal Death. 2013. http://www.cardiffandvaleuhb.wales.nhs.uk/opendoc/238496 (accessed 26 August 2015). [ Links ]

13. Alberta Cemeteries Act RSA 2000 CC-3. www.qp.alberta.ca/documents/Acts/C03.pdf (accessed 26 August 2015). [ Links ]

14. S v Mshumpa 2008 1 SACR 126 (E).

15. S v Molefe 2012 (2) SACR 574 (GNP) at 578.

16. Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pa. v Casey, 505 U.S. 833 (1992).

17. Royal College of Nursing. RCN Gynaecology Nursing Forum Working Group Sensitive Disposal of all Foetal Remains: Guidance for Nurses and Midwives. London: Royal College of Nursing, 2007. https://www2.rcn.org.uk/_data/assets/pdf_file/0020/78500/001248.pdf (accessed 7 March 2016). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

L du Toit-Prinsloo

lorraine.dutoit@up.ac.za

Accepted 23 October 2015.