Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.106 n.4 Pretoria Apr. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2016.v106i4.10441

CME

ARTICLES

DOI:10.7196/SAMJ.2016.V106I4.10441

Acute viral bronchiolitis in South Africa: Diagnostic flow

D A WhiteI; H J ZarII; S A MadhiIII; P JeenaIV; B MorrowV; R MasekelaVI; S RisengaVII; R J GreenVIII

IMB BCh, FC Paed (SA), MMed (Paed), Dip Allerg (SA), Cert Pulmonology (SA) Paed; Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIMB BCh, FC Paed (SA), PhD; Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Red Cross War Memorial Children's Hospital, and MRC Unit on Child and Adolescent Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

IIIMB BCh, MMed (Paed), FC Paed (SA), PhD; Medical Research Council: Respiratory and Meningeal Pathogens Research Unit, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

IVMB ChB, FC Paed (SA), Cert Pulmonology (SA) Paed; Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

VBSc (Physio), PG Dipl Health Research Ethics, PhD; Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa

VIMB BCh, MMed (Paed), Cert Pulmonology (SA) Paed, Dip Allerg (SA), FCCP, PhD; Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

VIIMB ChB, FC Paed (SA), Dip Allerg (SA), Cert Pulmonology (SA) Paed; Department of Pulmonology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Limpopo, Polokwane, and Pietersburg Hospital, South Africa

VIIIPhD, DSc; Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria, and Steve Biko Academic Hospital, Pretoria, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Bronchiolitis may be diagnosed on the basis of clinical signs and symptoms. In a young child, the diagnosis can be made on the clinical pattern of wheezing and hyperinflation. Clinical symptoms and signs typically start with an upper respiratory prodrome, including rhinorrhoea, low-grade fever, cough and poor feeding, followed 1 - 2 days later by tachypnoea, hyperinflation and wheeze as a consequence of airway inflammation and air trapping. The illness is generally self limiting, but may become more severe and include signs such as grunting, nasal flaring, subcostal chest wall retractions and hypoxaemia. The most reliable clinical feature of bronchiolitis is hyperinflation of the chest, evident by loss of cardiac dullness on percussion, an upper border of the liver pushed down to below the 6th intercostal space, and the presence of a Hoover sign (subcostal recession, which occurs when a flattened diaphragm pulls laterally against the lower chest wall). Measurement of peripheral arterial oxygen saturation is useful to indicate the need for supplemental oxygen. A saturation of <92% at sea level and 90% inland indicates that the child has to be admitted to hospital for supplemental oxygen. Chest radiographs are generally unhelpful and not required in children with a clear clinical diagnosis of bronchiolitis. Blood tests are not needed routinely. Complete blood count tests have not been shown to be useful in diagnosing bronchiolitis or guiding its therapy. Routine measurement of C-reactive protein does not aid in management and nasopharyngeal aspirates are not usually done. Viral testing adds little to routine management. Risk factors in patients with severe bronchiolitis that require hospitalisation and may even cause death, include prematurity, congenital heart disease and congenital lung malformations.

Clinical manifestations

Bronchiolitis is a viral-induced lower respiratory tract infection that occurs predominantly in children <2 years of age, particularly infants. Many viruses have been proven or attributed to cause bronchiolitis, including and most commonly the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and rhinovirus. Bronchiolitis may be diagnosed on the basis of clinical signs and symptoms. In a young child, the diagnosis can be made on the clinical pattern of wheezing and hyperinflation.

Clinical symptoms and signs typically start with an upper respiratory prodrome, including rhinorrhoea, low-grade fever, cough and poor feeding, followed 1 - 2 days later by tachypnoea, hyperinflation and wheeze as a consequence of airway inflammation and air trapping.[1] The illness is generally self limiting, but may progressively become more severe and include signs such as grunting, nasal flaring, subcostal chest wall retractions and hypoxaemia.[2] The most reliable clinical feature of bronchiolitis is hyperinflation of the chest, evident by loss of cardiac dullness on percussion, an upper border of the liver pushed down to below the 6th intercostal space, and the presence of a Hoover sign (subcostal recession, which occurs when a flattened diaphragm pulls laterally against the lower chest wall).

Measurement of peripheral arterial oxygen saturation is useful to indicate the need for supplemental oxygen. A saturation of <92% at sea level and 90% inland indicates that the child requires hospital admission for supplemental oxygen.

Investigations

Chest radiographs

Chest radiographs (CXRs) are generally unhelpful and not required in children with a clear clinical diagnosis of bronchiolitis.

Risk of airspace disease appears to be particularly low in children with saturation >92% and with mild to moderate distress.[3] A temperature >38°C has been shown to be a clinical predictor of radiographic abnormalities.[4]

CXRs in bronchiolitis show signs of hyperinflation, peribronchial thickening or patchy areas of consolidation and collapse, which may be confused with signs of pneumonia. A CXR should only be done in the following instances:[2,4,5]

- if complications are suspected, e.g. pleural effusion or pneumothorax

- severe cases

- temperature >38°C

- uncertain diagnosis

- if the child fails to improve or if their condition deteriorates.

Haematology

Blood tests are not needed routinely. Complete blood count tests have not been shown to be useful in diagnosing bronchiolitis or guiding its therapy.[2] Routine measurement of C-reactive protein does not aid in manage-ment.[6]

If the infant appears severely ill, consider alternative diagnoses (bacterial co-infection and other causes of airway obstruction). Clinical signs of concern include pallor, lethargy, severe tachycardia, high temperature, hypotonia or seizures. In cases of serious sepsis investigations may include a CXR, blood culture, and urinary and cere-brospinal fluid analysis.[5]

Nasopharyngeal aspirates

Nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPAs) are not usually taken and viral testing adds little to routine management,[7] but NPAs are needed to inform surveillance, measuring burden of disease and also in the following cases:[5,7]

- neonates (<1 month)

- history of apnoea with illness

- bed management to allow cohorting of patients.

NPAs should be immersed in viral transport medium at4- 8°C and transported to an appropriate laboratory within 72 hours of collection. Specimens should be tested by multiplex real-time reverse-transcription poly-merase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) assay for respiratory viruses. Comparative studies have shown that rRT-PCR assays are substantially more sensitive than conventional methods, such as viral culture and immunofluorescence assays, for detecting respiratory viruses.[8]

Furthermore, multiplex rRT-PCR has a significant advantage, as it permits simultaneous amplification of several viruses in a single reaction, facilitating a cost-effective diagnosis.[8]

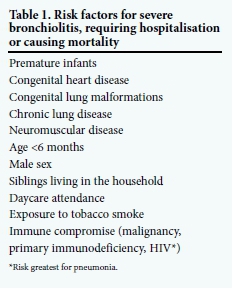

Risk factors for severe disease

In infants and young children respiratory viruses have the propensity to produce more serious lower respiratory tract illnesses, bronchiolitis and pneumonia. Infants <1 year of age are at greatest risk of bronchiolitis, and the disease is more severe when risk factors are present (Table 1).[9-15]

Debate about the importance of respiratory syncytial virus infection as a cause of hospitalisation in late preterm infants has raged because of the cost of prophylactic therapy. Recent reports have suggested that these infants are at equal risk and require prophylaxis.[16,17]

South African studies have revealed that the mean duration of symptoms following bronchiolitis was 12 days (95% confidence interval 11 - 14 days). After 21 and 28 days, 18% and 9%, respectively, were still ill. Thirty-four percent of these children were seen by a physician during an unscheduled visit.[18]

Finally, the respiratory viruses, especially RSV, may predispose to recurrent episodes of wheezing and possibly asthma.[19,20]

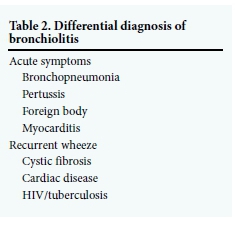

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of respiratory symptoms is wide, but where hyperinflation and wheeze occur the conditions listed in Table 2 should be considered.

References

1. Wohl MEB. Bronchiolitis. In: Chernick V, Boat TF, Wilmot RW, Bush A, eds. Kendig's Disorders of the Respiratory Tract in Children. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2006:423-432. DOI:10.1016/B978-0-7216-3695-5.50029-8 [ Links ]

2. American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Diagnosis and Management of Bronchiolitis. Diagnosis and management of bronchiolitis. Pediatrics 2006;118(4):1774-1793. DOI:10.1542/peds.2006-2223 [ Links ]

3. Schuh S, Lalani A, Allen U, et al. Evaluation of the utility of radiography in acute bronchiolitis. J Pediatr 2007;150:429-433. DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.01.005 [ Links ]

4. Ecochard-Dugelay E, Beliah M, Perreaux F, et al. Clinical predictors of radiographic abnormalities among infants with bronchiolitis in a pediatric emergency department. BMC Pediatrics 2014;14:143. DOI:10.1186/1471-2431-14-143 [ Links ]

5. Gavin R, Sheperd M. Starship Clinical Guideline. http://www.adhb.govt.nz/starshipclinicalguidelines/_Documents/Bronchiolitis.pdf (accessed 15 May 2015). [ Links ]

6. Moodley T, Masekela R, Kitchin O, Risenga S, Green RJ. Acute viral bronchiolitis. Aetiology and treatment implications in a population that may be HIV co-infected. S Afr J Epidemiol Infect 201025(2):6-8. [ Links ]

7. Zorc JJ, Hall CB. Bronchiolitis: Recent evidence on diagnosis and management. Pediatrics 2010;125:342-349. DOI:10.1542/peds.2009-2092 [ Links ]

8. Pretorius MA, Madhi SA, Cohen C, et al. Respiratory viral coinfections identified by a 10-plex real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction assay in patients hospitalized with severe acute respiratory illness - South Africa, 2009 - 2010. J Infect Dis 2012;206(S1):S159-S165. DOI: 10.1093/infdis/jis538 [ Links ]

9. Stein RT, Sherill D, Morgan WJ, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus in early life and risk of wheeze and allergy by age 13 years. Lancet 1999;354:541-545. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(98)10321-5 [ Links ]

10. Dominquez-Pinilla N, Belda Hofheinz S, Vivanco Martinez JL, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus in immunocompromised patients in a pediatric hospital: 5 years experience. An Pediatr (Barc) 2015;82(1):35-40. DOI:10.1016/j.anpedi.2014.04.016 [ Links ]

11. Cohen C, Walaza S, Moyes J, et al. Epidemiology of viral-associated acute lower respiratory tract infection among children <5 years of age in a high HIV prevalence setting, South Africa, 2009 - 2012. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015;34:66-72. DOI:10.1097/INF.0000000000000478 [ Links ]

12. Schuster JE, Williams JV. Human metapneumovirus. Pediatr Rev 2013;34:558-565. DOI:10.1542/pir.34-12-558 [ Links ]

13. Asner S, Stephens D, Pedulla P, Richardson SE, Robinson J, Allen U. Risk factors and outcomes for respiratory syncytial virus-related infections in immunocompromised children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2013;32:1073-1076. DOI:10.1097/INF.0b013e31829dff4d [ Links ]

14. Moyes J, Cohen C, Pretorius M, et al. Epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus-associated acute lower respiratory tract infection hospitalizations among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected South African children, 2010-2011. J Infect Dis 2013;208(Suppl 3):S217-S226. DOI:10.1093/infdis/jit479 [ Links ]

15. Tempia S, Walaza S, Viboud C, et al. Mortality associated with seasonal and pandemic influenza and respiratory syncytial virus among children <5 years of age in a high HIV prevalence setting - South Africa, 1998 -2009. Clin Infect Dis 2014;58:1241-1249. DOI:10.1093/dd/ciu095 [ Links ]

16. Resch B, Paes B. Are late preterm infants as susceptible to RSV infection as lull term infants? Early Hum Dev 2011;87(Suppl 1):S47-S49. DOI:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.01.010 [ Links ]

17. Madhi SA, Venter M, Alexandra R, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus associated illness in high-risk children and national characterisation of the circulating virus genotype in South Africa. J Clin Virol 2003;27:180-189. [ Links ]

18. Swingler GH, Hussey GD, Zwarenstein M. Duration of illness in ambulatory children diagnosed with bronchiolitis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000;154:997-1000. DOI:10.1001/archpedi.154.10.997 [ Links ]

19. Sigurs N, Gustafsson PM, Bjarnason R, et al. Severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis in infancy and asthma and allergy by age 13 years. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:137-141. DOI:10.1164/rccm.200406-730OC [ Links ]

20. Lotz MT, Moore ML, Peebles RS Jr. Respiratory syncytial virus and reactive airway disease. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2013;372:105-118. DOI:10.1007/978-3-642-38919-1_5 [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

D A White

debbie.white@wits.ac.za