Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.106 n.4 Pretoria Apr. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2016.v106i4.10623

EDITORIAL

Unpacking the new proposed regulations for South African traditional health practitioners

Traditional health practitioners (THPs) are an integral part of the history and culture of South Africa (SA). Many traditional healers and users of traditional medicine agree that there is a need to regulate the system. To this end, over the years, healers have initiated over 100 different traditional healer associations countrywide.[1,2] More recently, however, steps have been taken to regulate the estimated 200 000 THPs[3] under one professional statutory body.[4]

The Traditional Health Practitioners Act

The Traditional Health Practitioners Act 22 of 2007[4] aims to: (i) create an Interim Traditional Health Practitioners Council; (ii) provide a regulatory framework to ensure the efficacy, safety and quality of traditional healthcare services; and (iii) provide for the management and control over the registration, training and conduct of practitioners, students and specified categories in the THP profession. The Act defines four categories of THPs, namely diviners (sangoma), herbalists (inyanga), traditional birth attendants (ababelethisi) and traditional surgeons (ingcibi).

The establishment of a new Council

Under the Act,[4] the Interim Traditional Health Practitioners Council, appointed by the Minister of Health, should comprise one THP per province as well as a representative of each of the four THP categories. Over and above this, the Council must also include a legal expert, a member of the Health Professions Council of SA (a medical practitioner), a member of the SA pharmacy council (a pharmacist), community representatives and representatives of the Department of Health. In early 2013, the Council was inaugurated5 and the sections of the Act that allowed the Council to become functional came into effect on 1 May 2014.[6] The mandate of the Council is drawn from the Bill of Rights in the SA Constitution, the National Health Act 61 of 2003 as well as the THP Act 22 of 2007.[5] The interim Council now has extensive powers to oversee the registration and regulation of the practice of THPs by setting practice standards.

The proposed regulations

On 3 November 2015, after consultation with the interim Council, the Minister of Health published the much-anticipated THP Regulations to elicit comments from interested persons.[7] However, the lack of substantive detail in the proposed regulations leaves a lot of room for interpretation and speculation. In four brief pages, a regulatory framework for traditional healers, students (abatwasa) and trainers is proposed. This is followed by three separate pro forma regist ration documents for THPs, students and/or trainers. It is not clear whether all registrations will commence simultaneously or in a step-wise manner. The latter seems more plausible, as a knock-on effect is anticipated for certain registration categories.

Mandatory registration for all SA THPs

In terms of section 21 of the Act, 'no person may practise as a traditional health practitioner within the Republic unless he or she is registered in terms of this Act'. Section 21 of the Act also clearly states that an application must be accompanied by proof that the applicant is an SA citizen. The fact that only SA citizens may apply for registration will have financial consequences for foreigners currently offering traditional healing services. Apart from an SA identity document, further required documentation listed in the pro forma document includes 'proof of qualification as THP (if any)' and 'highest standard passed (attach certified copy, if any)'. It is not clear if registration will continue even if those documents do not exist.

The next schedule of the Regulations states that all THPs 'must undergo education or training at any accredited training institution or educational authority or with any traditional tutor'. The relationship between the schedules relating to registration and training is unclear. Will registration be delayed or conditional until a THP has undergone specified training? Even more elusive are the minimum standards and levels of training.

Minimum training standards for student THPs

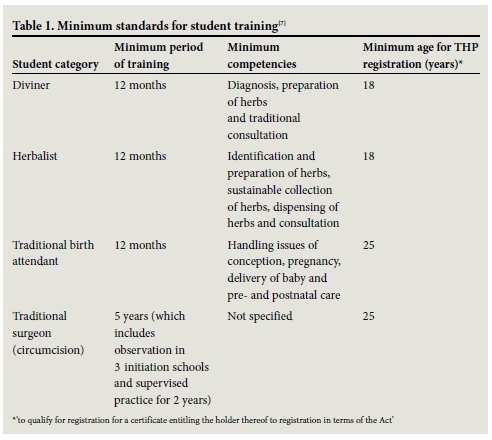

Unlike for current practising THPs, minimum requirements for prospective student THPs are clearly outlined and nobody is allowed to start traineeship unless he or she is registered as a student. Once again, the proposed regulations stress an SA identify document as a necessary supporting document. Minimum education, length of training and minimum age are the three items specified for student THPs (Table 1). All student THPs need to provide proof of adult basic education and training (ABET) level 1 or equivalent. The longest training period is for a traditional surgeon, whereby the trainee must conduct observation in three initiation schools and do supervised practice for 2 years, bringing the full training to a minimum of 5 years. The minimum age for registration as a traditional surgeon and traditional birth attendant are the same -25 years of age. It is not clear why a potential traditional birth attendant should wait until he or she is at least 25 years of age considering that the training programme need only be 12 months long and that no prerequisite education is required other than ABET level 1. For all categories, after training, the registered student will need to submit a logbook to the Council that details the observations and procedures undertaken.

Accreditation system for trainers and training institutions

Under the Act,[4] an 'accredited institution' means 'an institution, approved by the Council, which certifies that a person or body has the required capacity to perform the functions within the sphere of the National Quality Framework (NQF) contemplated in the SA Qualifications Authority Act 58 of 1995'. The NQF has been specifically designed to integrate education and training into a single framework, and combine separate education and training systems into a single, national system.[8] The proposed Regulations do not prescribe specific content or a curriculum for training, but the section under minimum standards for student training (Table 1) provides a very general outline of what is expected. In the list of supporting documents for trainers is the request for copies of teaching/learning materials. However, the actual process for vetting the submitted curricula is not provided. It is also not clear how the submission of training materials by individual THPs may culminate into a national training programme under the NQF. The submission of teaching/learning materials to the Registrar and/or Council is noteworthy and part of a larger discourse regarding intellectual property rights. Intellectual property rights are at the epicentre of numerous contemporary policy debates, both locally and abroad[9] and the proposed Regulations are timely with the recently published draft Protection, Promotion, Development and Management of Indigenous Knowledge Systems Bill by the SA Department of Science and Technology.[10]

Conclusions

SA has legislation that regulates almost all of its healthcare systems.[2] The THP Act finally provides legitimisation of an overwhelmingly popular indigenous healthcare system. However, as a consequence of the legal acknowledgement of THPs, traditional medicine products must now also be brought under regulatory measures. If traditional medicines are to be prescribed, marketed and sold as part of a healthcare system recognised under SA law, they must meet the same stringent standards.[3]

Acknowledgement. The content is solely the responsibility of the author and does not necessarily represent the official views of the South African Medical Research Council or the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

R A Street

Environment and Health Research Unit, South African Medical Research Council, Durban, South Africa, and Discipline of Occupational and Environmental Health, School of Nursing and Public Health, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

References

1. Pretorius E. Traditional healers. S Afr Health Rev 1999:249-256. [ Links ]

2. Gqaleni N, Moodley I, Kruger H, Ntuli A, McLeodiv H. Traditional and complementary medicine: Healthcare delivery. S Afr Health Rev 2007:175-188. [ Links ]

3. Hassim A, Heywood M, Berger J. Health and Democracy: A Guide to Human Rights, Health Law and Policy in Post-apartheid South Africa. Cape Town: Siber Ink, 2007. [ Links ]

4. South African Department of Health. Traditional Health Practitioners Act 22 of 2007. Pretoria; Department of Health, 2007. [ Links ]

5. South African Department of Health. Interim Traditional Health Council Inaugurated. 2013. http://www.sabinetlaw.co.za/health/articles/interim-traditional-health-council-inaugurated (accessed 9 January 2016). [ Links ]

6. President of the Republic of South Africa. Commencement of certain sections of the Traditional Health Practitioners Act Proclamation, 2007 (22 of 2007). Proclamation Notice No. 29 of 2014. In: Government Gazette No. 37600. Pretoria: Government Printing Works, 2014. [ Links ]

7. South African Department of Health. Notice 1052: Traditional Health Practitioners Regulations 2015. In: Government Gazette No. 39358. Pretoria: Government Printing Works, 2015. [ Links ]

8. The South African Qualifications Authority (SAQA). The South African National Qualifications Framework. http://www.saqa.org.za/list.php?e=NQF (accessed 11 January 2016). [ Links ]

9. Teljeur E. Intellectual Property Rights in South Africa: An Economic Review of Policy and Impact. Johannesburg: The Edge Institute, 2003. [ Links ]

10. South African Department of Science and Technology. Notice 243 of 2015. Protection, Promotion, Development and Management of Indigenous Knowledge Systems Bill, 2014. Pretoria: Government Printing Works, 2015. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

R A Street

renee.street@mrc.ac.za