Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.106 no.4 Pretoria Abr. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2016.v106i4.10569

EDITORIAL

Where are the males? Diversity, proportionality and Health Sciences admissions

The demographic profile of students at South African (SA) medical schools has undergone significant changes in recent decades; there are now many more 'black' and female students than there were 2 decades ago.

The altered racial profile is obviously partly attributable to the end of formal discrimination, but more proximately, is largely the result of affirmative action policies that have favoured applicants from previously disadvantaged 'race' groups. Applicants from these groups may be admitted with lower entrance scores.

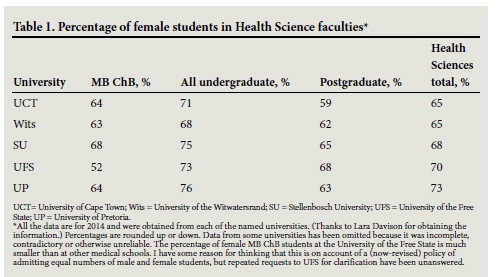

The increase in the number of female students over the same 2-decade period is not attributable to an end of formal discrimination, which ended much earlier than discrimination against blacks, or to the introduction of affirmative action. For entirely different reasons, the balance of male and female students in MB ChB programmes has gradually shifted, with female students now the majority (Table 1). In this way, MB ChB programmes are no longer dissimilar from enrolments in allied health programmes, where females have long predominated.

The predominantly female enrolment -although not the product of affirmative action - sheds important light on rationales that are regularly provided for racial preference in admissions policies, not only in the country's medical schools but also throughout SA universities. It is therefore worth considering those rationales and the way they are illuminated by the asymmetrical proportion of male and female Health Sciences students.

Racial preference

One argument for racial preference is redress, in which the favouring of black students on the grounds of their race is justified as a measure to redress past injustices. Blacks, it is argued, are suffering the legacy of past discrimination. They are economically worse off and suffer consequent educational disadvantage at primary and secondary level. In other words, the metaphorical playing fields are not level and therefore some racial preference is necessary in order to redress this injustice.

An important challenge to this argument is that it cannot justify favouring those black applicants who are not suffering the legacy of past discrimination. Middle-class and wealthy black applicants, who have attended superior schools, may share a skin colour with those who are suffering the protracted effects of past discrimination; however, they are not themselves suffering those effects, and thus favouring them - as SA universities do - cannot be justified by the redress argument.

It is at this point that the diversity argument is invoked. According to this argument, it is important to have a diverse student body for any one of a number of possible reasons. However, the diversity argument is, in fact, not actually a diversity argument. The term diversity is imported from the USA where blacks are a minority of the population and where (far more modest) programmes of racial preference have been instituted in order to secure some minimal representation of African Americans in the student body.

In SA, where the majority of the population is black, diversity in this sense can be obtained even without the extreme forms of racial preference that constitute current policy. Thus when SA advocates of affirmative action employ the term diversity they actually mean proportionality. The goal is to have the racial demographics of the student population reflect the racial demographics of the country.

Proportions of males

Is proportionality a genuine commitment or is it rather a rationalisation of a preconceived idea about the justifiability of racial preference? The gender profile of Health Sciences students in SA provides a helpful test case. If there were a genuine commitment to proportionality, one would think that something would have been done about the dearth of males in SA medical schools. At the University of Cape Town (UCT), for example, only 36% of MB ChB students and only 35% of all students in the Faculty of Health Sciences are male. Those figures are far from reflective of the demographics of the country.

The figures for MB ChB (and some related programmes) are particularly important because there is a stronger case to be made for gender proportionality in medicine than in other areas of study. This is because many people have a reasonable preference for doctors of the same sex as themselves. Just as some women prefer to consult female doctors and physiotherapists and to be attended to by female nurses, so some men may prefer to consult and be cared for by male practitioners.

Such preferences have a rational basis.[1] The same cannot be said for preferences to have a lawyer, architect, engineer or quantity surveyor of a particular race or sex - or a doctor of a particular race. (To have a doctor who speaks one's language is a reasonable preference, but if that were the rationale for affirmative action then preference should be given not on the basis of race but rather on the basis of competence or fluency in a language underrepresented among medical practitioners.)

Possible responses

How might those who defend racial preference in admissions but who are unconcerned about the disproportionately few males in medical schools respond?

They might argue that there are not as disproportionately few males as there are blacks and therefore there is currently a much stronger proportionality-based case for racial preference than there is for favouring males in admissions to medical schools.

However, there clearly are some programmes in which males are a very tiny fraction of all students. For example, only 4.5% of BSc Speech-Language Pathology students at UCT are male, even though approximately 50% of all South Africans are males. If extremely disproportionate percentages were the basis for racial preference then the argument would also apply to those programmes in which males constitute an extremely small proportion of students.

Another possible argument is that males (qua males), unlike blacks, are not the victims of past discrimination and it is for this reason that racial preference is required. However, the proportionality argument is different from the redress argument. We have already seen that the redress argument does not apply to all blacks, which is exactly why defenders of racial preference in admissions retreat to the proportionality argument. Thus, the proportionality defence of racial preference cannot be rescued by appealing to a redress argument. This is because the redress argument does not apply to all those whom it favours, namely those blacks who suffer no disadvantage that needs to be redressed.

In response to this, it might be suggested that while economically and privileged blacks are not disadvantaged in those ways, they nonetheless are the victims of subtle forms of prejudice or discrimination that partially explain their underrepresentation in the absence of racial preference. However, if one wishes to advance that argument, then one may have to consider the possibility that (different) subtle forms of prejudice and discrimination explain part of the sex imbalance among Health Sciences students. When females are underrepresented in the senior professoriate and in disciplines such as engineering, there is much handwringing and the assumption is that discrimination of some kind explains the problem. However, it is highly implausible to think that prejudice and discrimination are always to blame when women are underrepresented in desirable areas but that prejudice and subtle discrimination play absolutely no role when men are underrepresented.[2] For example, gender roles and the designation of some professions as 'female' may militate against males entering them. Consider, for example, the prejudices against male nurses.

The fact that these arguments fail suggests an inconsistent acceptance of the proportionality argument among those who invoke it in defence of racial preference and yet are happy to let the chips fall where they do when it comes to the disproportionately few males in medical schools.

What ought to be done?

The full argument advanced to defend current affirmative action admissions policies would suggest that the correct response to the disproportionately few males in various Health Sciences programmes would be a policy of sex-based preference for males. However, I have argued elsewhere against race-based preferences[3,4] and I similarly think that sex-based preference is problematic, whether the beneficiaries are male or female.[5]

This does not mean that nothing can be done about the uneven enrolments of males and females. There are forms of affirmative action that do not involve any noxious preferences. For example, one might, in the first instance, try to understand why more males with competitive matriculation marks are not applying for Health Sciences programmes (as they once did in the case of the MB ChB), preferring now instead to apply for other courses of study.[6] Therefore, some research needs to be done. With the results in hand, one would be better placed to determine whether careers in medicine and other healthcare professions could be made more attractive to males, thereby increasing the number of male applicants who could be admitted using the same criteria and standards as are used for female applicants.

D Benatar

Department of Philosophy, Faculty of Humanities, University of Cape Town, South Africa

References

1. Benatar D. The Second Sexism: Discrimination Against Men and Boys. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012:149-150. [ Links ]

2. Benatar D. The Second Sexism: Discrimination Against Men and Boys. Malden MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012. [ Links ]

3. Benatar D. Justice, Diversity and Racial Preference: A Critique of Affirmative Action, S Afr Law J 2008;125(2):274-306. [ Links ]

4. Benatar, D. Just admissions: South African universities and the question of racial preference. S Afr J High Educ 2010;24(2):258-267. [ Links ]

5. Benatar D. The Second Sexism: Discrimination Against Men and Boys. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012:212-238. [ Links ]

6. Ncayiyana DJ. Feminisation of the South African medical profession - not yet nirvana for gender equity S Afr Med J 2011;101(1):5. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

D Benatar

philosophy@uct.ac.za