Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.106 n.4 Pretoria Apr. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2016.v106i4.10765

IZINDABA

Vaccines: SA's immunisation programme debunked

South Africa (SA)'s high-priority, underfunded Expanded Programme on Immunisation (EPI) is understaffed and close to rudderless, with inaccurate data collection on vaccine coverage continuing apace while actual management of the programme deteriorates by the month.

The top national Department of Health (NDoH) EPI managers resigned in August and December last year, taking with them large chunks of institutional memory and invaluable expertise. SA remains in the top five underperforming EPI African countries (according to World Health Organization (WHO) standards), for the third year running. According to Johann van den Heever, the recently resigned (in December) national EPI manager, a 'lack of leadership vision' and a ZAR1.4 billion national budget provides exclusively for vaccine purchase, hugely under-prioritising human resources, social mobilisation and surveillance, supervision, and monitoring and evaluation. The ongoing frustrations of inaccurate and unscientific data collection, severe understaffing and lack of a pragmatic operational budget led to his resignation. A former Gauteng EPI and communicable diseases specialist (8 years), he has spent the past 11 years as national EPI manager. His national senior specialist, Dr Ntombenhle Ngcobo, resigned last August, followed by their EPI data manager. None of this leadership had been replaced by early March this year. According to Van den Heever, only six of the original 13 national EPI posts (created in 1994) remain, all with relatively junior incumbents, making basic data quality audits and accurate evaluations for immunisation even more difficult. The NDoH's national vaccination coverage figure stands at 90% - a full 20% higher than the WHO/UNICEF estimate (a sore point with both parties).

Calling into question the NDoH and WHO estimates, Van den Heever says that SA has little idea of its infant population, upon which any vaccine coverage estimate must be based. It was 'absolutely imperative' for any national health immunisation programme to have an electronic register of its target population (starting with infants), supported by a national EPI coverage survey to provide a performance measurement baseline. By having an immunisation register linked to the procurement of vaccines, the country would save millions of rands. There never seemed to be any money for operational costs. 'If you don't have money for proper support, monitoring and evaluation in the provinces, don't hold quarterly EPI provincial manager meetings to strengthen all aspects of the programme, including surveillance, or fail to interrogate the data and progress, or have an opportunity to do training, supervision and motivation of staff - and you replace all this with maybe one teleconference per province per year - you could end up with a huge problem,' he said. Late, incomplete data were being used, with some of the country's 52 health districts at times not entering any data for up to 3 months, while others had 'very poor' immunisation coverage. District Health Information System (DHIS) staff were supposed to send the data to the provincial health departments and then to the national District Health Information Unit, which then forwarded the data to the (now non-existent) national EPI manager. Routine data (denominators) collected through the DHIS did not include all doses of all antigens administered. There are just no proxies for antigens administered. If some vaccines at, say, 6 weeks of (infant) age were out of stock, one could not 'assume' that all the 6-week doses were administered if only one of those doses (assumed to be proxy) was collected in the DHIS. This provided a false sense of the true coverage of all the 6-week doses administered. 'How they can then claim SA is doing a good job of immunisation is beyond my comprehension,' he said. An electronic register of births, which with the support of the Department of Home Affairs could strengthen the Stats SA annual birth cohort denominators to the NDoH, with reliable figures up to subdistrict or health facility level, would already be a significant contribution towards more accurate calculation of immunisation coverage. The WHO recommended that countries conduct a national EPI coverage survey every 5 years, with the provinces completing one every 3 years, yet this was not done. Home Affairs and Stats SA were unable to provide government with a denominator with which to calculate vaccination coverage. The possibility of a WHO-acceptable national EPI coverage survey was explored with UNICEF and the WHO in November 2013 (and costed at ZAR20 million), but never got off the ground. 'If we ever have a true polio case we wouldn't be able to detect it in time before many others were infected, because we are not meeting the WHO-required EPI priority disease surveillence standards,' he added.

National cold-chain manager, Mr Sim Langa admitted that he was understaffed. He said he adapted by identifying and supporting poorly performing districts, and 'depending on resources' checked up on between 5% and 10% of all vaccination facilities.

Van den Heever said it was therefore 'impossible to say' how much of the ZAR1.4 billion worth of vaccines was actually going into children, what percentage was expiring as a result of inaccurate stock control, and how much was being thrown away because of cold-chain mismanagement or non-WHO-compliant refrigerators. Prof. Shabir Madhi, Executive Director of the National Institute of Communicable Diseases and Deputy Chairperson of the National Advisory Group on Immunisation, told Izindaba that without a national audit of vaccine storage and reliable, accurate figures of children vaccinated and meeting vaccine-preventable disease surveillance standards, at all facilities, it was impossible to estimate coverage or vaccine-related mortality and morbidity. He said that the Office for Healthcare Standards Compliance was due to present an audit of all facilities to government 'within weeks'. However, this would be far broader than vaccines. He confirmed that all facilities were meant to use WHO-approved vaccine-only fridges. Mahdi is internationally recognised for his research on the safety, immunogenicity and efficacy of vaccines for child populations.

National cold-chain manager: 'we inspect 5 - 10% of facilities'

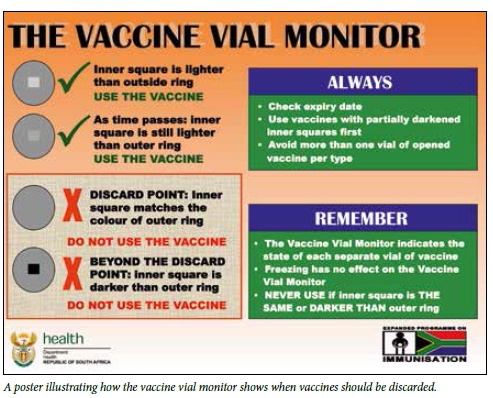

Van den Heever said the national cold-chain manager responsible for vaccine supply and quality control, Mr Sim Langa, was 'hugely overworked'. Langa admitted that he was understaffed. He said he adapted by identifying and supporting poorly performing districts and 'depending on resources' checked up on between 5% and 10% of all vaccination facilities (of which there are 3 000 - 4 000). 'If I had a magic wand I'd want a system that enables me to inspect temperature ranges nationally. The cold chain management is not perfect,' he added. Van den Heever said that provincial inventories of cold-chain equipment down to facility level were simply not kept. If the cold chain broke, senior clinical staff often took vaccines home to store in their own (inappropriate) fridges. Every WHO-approved fridge is supposed to have an internal continuous monitoring device with a temperature chart on the outside on which readings are manually recorded twice a day to ensure that vaccines remain at between 2oC and 8oC. However, in practice fridges had been found with insulin and HIV medication (incorrectly) stored with the vaccines. This leads to constant opening and closing of the fridge door and inevitable breaks in the required vaccine temperature range. All vaccine vials carry a temperature and time-sensitive vaccine vial monitor tag of a light square within a dark circle. If the square turns the same colour as the circle or becomes darker, or the date on the vial is beyond its expiry date, the vial must be discarded. Van den Heever said that when vaccines lost efficacy/potency it was usually due to overstocking of vaccines or temperature control dysfunction. 'And if they run out, they borrow from the clinic next door and don't record it. One simply doesn't know how effective vaccine management is at facility level,' he said.

Prof. Gregory Hussey, Dean of the Faculty of Health Sciences at the University of Cape Town and Chairperson of the National Advisory Group on Immunisation, said his committee was meeting national Minister of Health Dr Aaron Motsoaledi and senior vaccine programme directors at the end of March and would emphasise the importance of a better operational EPI budget. He said the challenge had been to underpin the introduction of vaccines with sound managerial expertise which was devolved via individual provinces to their district health services. If there had been serious cold-chain failures, there would have been major outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases (like the KwaZulu-Natal diphtheria outbreak last year). He admitted that, at EPI national level, 'there are issues and we need to take them seriously'.

Senior EPI specialist identifies shortcomings

Ngcobo confirmed that data from the DHIS were poor, and said the WHO and UNICEF simply ignored them. The true vaccination percentage probably lay somewhere between the overinflated DHIS figures and the more conservative WHO/UNICEF estimates. She agreed with Van den Heever that not conducting a national EPI coverage survey and failing to assessing stock availability countrywide were major problems. She singled out the widespread practice of allocating the pharmacy assistant job to nursing assistants at clinics, saying that the latter resented the job and put in no effort, resulting in poor stock management. A study of 31 Tshwane (Pretoria) clinics she conducted in April last year showed that most had stock-outs for 2 weeks to a month, especially of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine, rotavirus and the pentavalent vaccine. The causes were poor stock management, unreliable deliveries, lack of pharmacy assistants and limited fridge capacity. Their emergency ordering system was also dysfunctional. Ngcobo recommended that the entire Tshwane supply chain be restructured and overhauled, using modern technology. 'You can just imagine what happens to rural Transkei and Zululand,' she added.

The NDoH recently piloted an electronic medicines surveillance system at 39 (of over 500) public sector hospitals to 'strengthen demand planning and governance', and in August 2014 instituted the cellphone SMS (text message) MomConnect programme, which now has 42 000 pregnant women subscribers who receive term-tailored health messages. Both initiatives, although in their infancy, hold long-term promise in helping to address EPI problems.

Chris Bateman

chrisb@hmpg.co.za