Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.106 n.3 Pretoria Mar. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/samj.2016.v106i3.9877

IN PRACTICE

MEDICINE AND THE LAW

Amendments to the Sexual Offences Act dealing with consensual underage sex: Implications for doctors and researchers

S BhamjeeI; Z EssackII; A E StrodeIII

ISenior lecturer in the School of Law, University of KwaZulu-Natal (Pietermaritzburg), South Africa. She is also a consultant to the HIV/AIDS Vaccines Ethics Group, University of KwaZulu-Natal (Pietermaritzburg)

IISenior research specialist at the Human Sciences Research Council, an Honorary Research Fellow at the School of Law, University of KwaZulu-Natal (Pietermaritzburg), and a consultant to the HIV/AIDS Vaccines Ethics Group

IIISenior lecturer in the School of Law, University of KwaZulu-Natal (Pietermaritzburg), and a consultant to the HIV/AIDS Vaccines Ethics Group

ABSTRACT

In terms of the Sexual Offences and Related Matters Amendment Act, consensual sex or sexual activity with children aged 12 - 15 was a crime, and as such had to be reported to the police. This was challenged in court in the Teddy Bear case, which held that it was unconstitutional and caused more harm than good. In June 2015, the Amendment Act was accepted by both the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces, and came into operation on 3 July 2015. This article looks at the amendments to sections 15 and 16 of the Act and what the reporting obligations for medical professionals and researchers are in light of the amendments, as well as the duty to provide medical services and advice to adolescents.

South Africa (SA) has a very progressive legal framework which provides that adolescents have a right (largely) from the age of 12 to access a range of sexual and reproductive health services including contraceptives, treatment for sexually transmitted infections and termination of pregnancy (Table 1).[1-2] However, consensual but underage sex was a criminal offence that had to be reported to the police.[3] These conflicting approaches between the various branches of law placed doctors, researchers and other practitioners working with adolescents in an invidious position where they had a duty to provide adolescents with sexual and reproductive services but were required to report all sexual acts (including consensual 'offences') against children.[4]

In the Teddy Bear Clinic case[6] these issues came before the Constitutional Court when it considered whether criminalising consensual, underage sex and sexual activity violated the constitutional rights of children.[5] The Constitutional Court held that adolescents have a right to engage in healthy sexual behaviour and that such acts were part and parcel of normative development from adolescence to adulthood.[6] The Court held further that criminalising consensual sex or sexual activity between adolescents aged 12 - 15 violated their rights to privacy, bodily integrity and dignity.[6] Criminalising such behaviour was also not in the best interests of the affected children.[1,2,6] The Court ordered Parliament to amend the Act and bring it in line with the Constitution.[6] Parliament recently did this by passing the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act in 2015 (hereafter 'the Act').[7] The Act amends sections 15 and 16 (among others) of the Sexual Offences Act, which are the sections that deal with consensual underage sex or sexual activity.[7] This article sets out the provisions in the new Act dealing with consensual underage sex and sexual activity, indicates how the law has changed from the previous position, and explores the impact that this will have for doctors, researchers and other service providers working with adolescents.

The Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act 5 of 2015

The Act[7] provides firstly, in section 15 with regard to consensual sexual penetration with certain children (statutory rape), that:

'S15 (1) A person ("A") who commits an act of sexual penetration with a child ("B") who is 12 years of age or older but under the age of 16 years is, despite the consent of B to the commission of such an act, guilty of the offence of having committed an act of consensual sexual penetration with a child, unless A, at the time of the alleged commission of such an act, was -

(a) 12 years of age or older but under the age of 16 years; or

(b) either 16 or 17 years of age and the age difference between A and B was not more than two years.'

This means that it is no longer a criminal offence for adolescents to engage in consensual sex with other adolescents aged 12 - 15 years.[5] It will also not be a criminal offence if the one adolescent is between the ages of 12 and 15 and the other is 16 or 17, provided that there is not more than a 2-year age gap between the parties.

Secondly, with regard to sexual violation (statutory sexual assault), the Act provides in section 16 that:

'S16. (1) A person ("A") who commits an act of sexual violation with a child ("B") who is 12 years of age or older but under the age of 16 years is, despite the consent of B to the commission of such an act, guilty of the offence of having committed an act of consensual sexual violation with a child, unless A, at the time of the alleged commission of such an act, was -

(a) 12 years of age or older but under the age of 16 years; or

(b) either 16 or 17 years of age and the age difference between A and B was not more than two years.'

In section 1 of the Sexual Offences Act many forms of sexual expression and experimentation, including kissing, mutual masturbation, or touching of genital organs, breasts, or any part of the body resulting in sexual stimulation, are considered to be a form of sexual violation.[3] These acts will no longer be a criminal offence, provided that both adolescents are between the ages of 12 and 15 years or one adolescent is aged between 12 and 15 and the other is 16 or 17, and there is not more than a 2-year age gap between them.

Similarities and differences between the approach to consensual, underage sex in the Sexual Offences Act 2007 and the Amendment Act

There are a number of similarities in the approach taken in the old Sexual Offences Act and the new Amendment Act, namely:

- The age of consent to sex or sexual activity remains 16 years.[7]

- The age below which a child does not have the capacity to consent to sex or sexual activity remains 12 years.[7]

- The mandatory obligations regarding the reporting of any sexual offence against a child remain in place. Section 54 of the Sexual Offences Act has not been amended. There is therefore an 'obligation to report (the) commission of sexual offences against children ...'.[7]

- Adults or older persons who have sex or engage in sexual activity with adolescents will still be committing a crime.

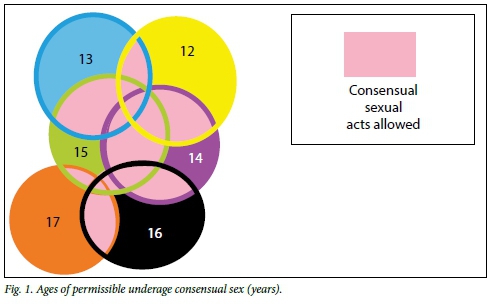

There are two main differences in approaches between the old and the new laws. Firstly, peer-group sex and sexual activity between adolescents has been decriminalised. This introduces a new era into our law in terms of which peer-group sex or sexual activity between adolescents is no longer a criminal offence. Fig. 1 illustrates the age spans for decriminalised consensual sex and sexual activity (where the circles overlap, e.g. 12, 13, 14 or 15, sex or sexual activity between those ages is permissible) and where sex and sexual activity remains a criminal offence (where there is no overlap, e.g. 13 and 16, sex or sexual activity between those ages is not permissible).

Secondly, the 2-year 'close-in-age' defence has been expanded to include sexual violation. This means that it is no longer an offence if a 16- or 17-year-old engages in a sexual act (violation or penetration as defined in the Act) with an adolescent aged between 12 and 15 years, provided they are not more than 2 years older than the younger partner. This inclusion is in line with the proposal made by the applicants in the Teddy Bear case, who argued that adolescents aged 15 - 17 are part of the same peer group given that they complete grades 10 - 12 together. Such peer group relationships would be normative, and therefore should not be criminalised.[8] The inclusion of the close-in-age defence brings our law in line with the approaches adopted in the UK,[9] Canada[10] and various jurisdictions in the USA.[11] While in some countries close-in-age defences are used to impose lighter penalties on adolescents, in others, such as SA, such defences decriminalise the activity altogether.[12] In recognition that the age of majority is 18, this defence helps protect 16- and 17-year-olds (who are still legally children) from prosecution, as long as they are not more than 2 years older than their younger sexual partner.

Implications of the new Act for doctors and researchers

The main implication for doctors and researchers is that the ethical dilemma they faced regarding reporting consensual sex or sexual activity when providing sexual and reproductive services or undertaking research with adolescents has largely fallen away. Although the Act does not amend the provisions on mandatory reporting, they have been limited by the narrowing down of the activities that are criminalised. This means that doctors and researchers do not need to report such activity unless (Table 2):

- One of the parties was under the age of 12

- The activity was non-consensual

- The younger participant was 12 - 15 years old and the older participant 16 - 17, and the age difference between them was more than 2 years at the time of the act

- The younger participant was 12 - 15 years old and their partner was an adult.

However, the changes to the law do not completely resolve the ethical conflicts for doctors and other service providers, as indicated in the following instances. Firstly, with regard to termination of pregnancy, a girl under the age of 12 has a right to choose to terminate a pregnancy provided that she has sufficient capacity to make this decision.[6,13] However, given that her consent to sex is not legally valid, the offence of rape has occurred against her and it must be reported. This leaves service providers in a difficult position, as reporting in this instance may lead to girls choosing to have 'back-street' abortions as a way of avoiding their partner being charged with a criminal offence.

Secondly, in terms of the Children's Act, a child under the age of 12 may consent to HIV testing independently if they have 'sufficient maturity'.[14] Consequently, a service provider may become aware that a child is sexually active below the age of 12 when the child requests HIV testing. Again, as with terminations of pregnancy in this age group, this information places the service provider under an obligation to breach the confidential patient-provider relationship and disclose this information to the police, thus discouraging young persons from coming forward and accessing HIV testing.

Thirdly, in line with the Children's Act[14] and the Termination of Pregnancy Act,[15] healthcare providers are still required to ensure access to sexual and reproductive healthcare services for adolescents, regardless of whether the sex was consensual/ non-consensual or whether it triggered mandatory reporting responsibilities. Again this poses an ethical dilemma, as some adolescents who have been the victims of crimes such as child abuse may want sexual and reproductive health services but do not wish the service provider to report information relating to such services to the police.

Fourthly, reporting consensual sexual relationships between adolescents and their older partners will remain a key ethical complexity.[2] Recent research indicated that among adolescents, significantly more females than males had partners who were at least 1 year older than them.[16] Furthermore, one-third (33.6%) of females and 4.1% of males aged 15 - 19 years reported having sex with partners who were 4 years or more older.[17] Girls (and to a lesser extent boys) in these discordant relationships will still be affected by the criminal law as their partners are committing an offence to which they are a witness, and they may be required, among other things, to give evidence to incriminate their partner. Again, reporting such intergenerational sex may create mistrust and unease in the therapeutic and research relationship and result in a refusal to disclose partners' ages, which may impact on prevention services and counselling.[2,4]

In terms of research, the Act allows for an increase in the scope of potential socially valuable research with young adolescents. It has been noted that there is a paucity of empirical research with pubescent girls and boys, which creates missed opportunities for public health interventions for this age group.[18-19] It is contended that one reason for the limited research on sex and sexuality among early adolescents is the previously restrictive legal framework, which created conundrums for researchers who would be legally obliged to report the activity, but ethically required to maintain confidentiality.[2,4,19] Recent amendments may therefore expand the scope of research, minimise ethical conflicts for researchers, and also minimise the potential risks of participating in research for this already vulnerable age group.[19]

Conclusions

The Amendment Act is a significant step forward for children's rights. It has eased tensions that existed between the Children's Act[14] and the Sexual Offences Act.[3] This

will facilitate both research with, and service provision for, adolescents. Nevertheless, both healthcare providers and researchers must be aware of the particular circumstances that would activate their mandatory reporting responsibilities in the course of providing healthcare services or conducting research. Researchers should develop an informed, nuanced approach to intergenerational sex that is approved by research ethics committees, as argued in earlier articles.[4]

Recommendations

- All service providers who are involved in the care of children should be informed of amendments to the Sexual Offences Act that clearly articulate that the age of consent to sex remains at 16 and that sex and sexual activity in certain age categories have been decriminalised, and the implications for service delivery and mandatory reporting.

- The recently updated Department of Health guidelines on ethics in health research[20] should amend the section on the mandatory reporting of abuse to reflect recent changes in the criminal law.

- Researchers working with adolescents should ensure that any standard operating procedures relating to mandatory reporting reflect the narrower circumstances in which reporting will have to take place.

Funding acknowledgment and disclaimer. The work described was supported by award number 1RO1 A1094586 from the National Institutes of Health entitled CHAMPS (Choices for Adolescent Methods of Prevention in South Africa). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. It does not necessarily represent the views of any Council or Committee with which the authors are affiliated.

References

1. McQuoid Mason D. Mandatory reporting of sexual abuse under the Sexual Offences Act and the 'best interests of the child. S Afr J Bioethics Law 2011;3(2):75-78. [ Links ]

2. Strode A, Toohey J, Slack C, Bhamjee S. Reporting underage consensual sex after the Teddy Bear case: A different perspective. S Afr J Bioethics Law 2013;6(2):45-47. [http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAJBL.289] [ Links ]

3. Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act 32 of 2007. http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/population/aids/southafrica.sexoffenses.07.pdf (accessed 26 January 2016). [ Links ]

4. Strode A, Slack C. Sex, lies and disclosures: Researchers and the reporting of under-age sex. South Afr J HIV Med 2009;10(2):8-10. [ Links ]

5. Strode A, Slack C, Essack Z. Child consent in South African law: Implications for researchers, service providers and policy-makers. S Afr Med J 2010;100(4):247-249. [ Links ]

6. Teddy Bear Clinic for Abused Children and Another v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development and Another 2013 (12) BCLR 1429 (CC). [ Links ]

7. Criminal Law (Sexual Offences and Related Matters) Amendment Act 5 of 2015. http://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/38977_7-7_Act5of2015CriminalLaw_a.pdf (accessed 26 January 2016). [ Links ]

8. Teddy Bear Clinic for Abused Children and RAPCAN v Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development and National Director of Public Prosecutions 2013 (CCT12/2013). Applicants' heads of argument. [ Links ]

9. Sexual Offences Act 2003 (UK) c 42. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/42/contents (accessed 30 June 2015). [ Links ]

10. Tackling Violent Crime Act, 2908. http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/annualstatutes/2008_6/page-1.html (accessed 22 June 2015). [ Links ]

11. Davis NS, Twombly J. Handbook for Statutory Rape Issues. 2000. http://www.mincava.umn.edu/documents/stateleg/stateleg.pdf (accessed 15 June 2015). [ Links ]

12. Kern JL. Trends in teen sex are changing, but are Minnesota's Romeo and Juliet laws? William Mitchell Law Rev 2013;39(5). http://open.wmitchell.edu/wmlr/vol39/iss5/72013 (accessed 22 June 2015). [ Links ]

13. Christian Lawyers Association v Minister of Health and Others (Reproductive Health Alliance as Amicus Curiae) 2005 (1) SA 509 (TDP). [ Links ]

14. Children's Act, No. 38 of 2005 available from http://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/a38-05_3.pdf (accessed 26 January 2016). [ Links ]

15. Choice of Termination of Pregnancy Act No. 92 of 1996. http://www.saflii.org/za/legis/consol_act/cotopa1996325/ (accessed 26 January 2016). [ Links ]

16. Richter L, Mabaso M, Ramjith J, et al. Early sexual debut: Voluntary or coerced? Evidence from longitudinal data in South Africa - the Birth to Twenty Plus study. S Afr Med J 2015;105(4):304-307. http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.8925] [ Links ]

17. Simbayi LC, Shisana O, Rehle T, et al. South African national HIV prevalence, incidence and behaviour survey, 2012. Human Sciences Research Council. 2014. http://www.hsrc.ac.za/en/research-outputs/view/6871 (accessed 4 May 2014). [ Links ]

18. Sommers M. An overlooked priority: Puberty in sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Public Health 2011;101(6):979-981. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.300092] [ Links ]

19. Jewnarain D. The ethical dilemmas of doing research with 12-14 year-old school girls in KwaZulu-Natal. Agenda 2013;27(3):118-126. [ Links ]

20. Department of Health. Ethics in Health Research: Principles, Processes and Structures. 2nd ed. Department of Health, 2015. http://www.nhrec.org.za/docs/Documents/EthicsHealthResearchFinalAused.pdf (accessed 27 June 2015). [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

A E Strode

strodea@ukzn.ac.za

Accepted 15 November 2015.