Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.106 n.1 Pretoria Jan. 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2016.V106I1.10326

CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION

ARTICLE

An approach to the diagnosis and management of valvular heart disease

B J CupidoI; F PetersII; N A B NtusiIII

IFCP (SA), Cert Cardiology (SA); Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town and Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa

IIFCP (SA), Cert Cardiology (SA); Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand and Baragwanath Hospital, Johannesburg, South Africa

IIIFCP (SA), DPhil; Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town and Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Valvular heart disease poses a common yet difficult problem in everyday clinical practice. A thorough clinical evaluation with basic common investigations such as an electrocardiogram (ECG) and a chest radiograph (CXR) remains the cornerstone of diagnosis. Echocardiography and more invasive testing, if needed, are usually performed at specialist level to confirm the diagnosis, assess severity and assist in definitive decision-making.

The causes and clinical, ECG and CXR features of the common valve lesions are described. Patients with symptomatic valve lesions should be referred for specialist assessment. In most cases, medical therapy serves as a bridge to definitive mechanical or surgical therapy.

The diagnosis of valvular heart disease is a difficult problem in everyday clinical practice. There is a wide spectrum of presentation - in some cases murmurs are found incidentally and in others, patients present very late with dire haemodynamic consequences of neglected valve lesions that may preclude them from definitive surgery. This review serves as a guide to the primary care clinician in the diagnosis and management of valve disease.

With the decline in rheumatic heart disease and the ageing population in the developed world, there has been a change in the disease patterns of valve lesions over the last few decades. Western populations are experiencing greater numbers of degenerative valve disease. In the developing world, however, rheumatic heart disease remains an important cause of valve pathology. Sliwa et al.,[1]in the Heart of Soweto Study, showed an incidence of new cases of rheumatic heart disease of 23.5/100 000 cases per annum.

Clinical evaluation (history and examination) remains the corner- stone of screening for valve pathology. An electrocardiogram (ECG) and a chest radiograph (CXR) are seen as important adjuncts to clinical evaluation and may provide important diagnostic clues to confirming pathology.

Echocardiography with colour flow and Doppler (not focus- assessed transthoracic echocardiography (FATE) scans) plays a pivo- tal role in confirming the diagnosis, and assessing the severity of the valve lesions and concomitant pulmonary hypertension, other valve lesions and haemodynamic consequences.

Invasive testing with cardiac catheterisation is reserved for patients in whom there is a discrepancy between clinical findings and echocardiography.

Mitral stenosis

Mitral stenosis (MS) is almost exclusively caused by chronic rheumatic heart disease. The rheumatic process leads to inflammation, resulting in commissural fusion, thickening and fibrosis of both the leaflets and subvalvular apparatus. Fewer than half of patients with MS recollect an episode of acute rheumatic fever. Other rare causes of mitral valve (MV) obstruction include congenital MS, degenerative mitral annular calcification, atrial myxomas, large thrombus or vegetations, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and carcinoid syndrome.

A normal MV area is 4 - 6 cm2. During diastole, the MV opens to allow the unobstructed flow of blood into the left ventricle. With MS, there is obstruction to ventricular inflow; the resultant pressure gradient causes an increase in left atrial (LA) pressure. Pulmonary oedema usually occurs secondary to this rise in pressure.

Any condition that increases heart rate, including sepsis, thyroid disease, anaemia, atrial fibrillation (AF) and pregnancy, may precipi- tate symptoms.

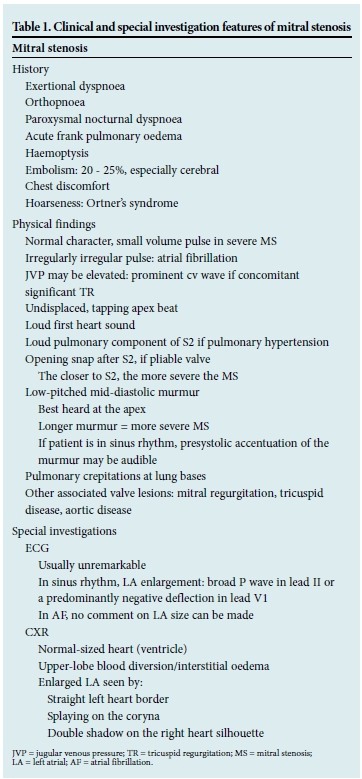

Clinical features and special investigation findings are described in Table 1.[2]

Patients with mild disease and symptoms may require diuretic therapy and sodium restriction to reduce congestion. Beta-blockers are often prescribed, the rationale being that reducing the heart rate increases diastolic filling time, reduces the gradient and improves effort tolerance. It is generally used in patients with Class II - III symptoms. There is no evidence for its prognostic benefit or use in multivalve disease.[2]

Verapamil may also be used for heart rate control, but should not be administered concomitantly with beta-blockers. There is no benefit from the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. Digoxin may be used for heart rate control in patients with AF, but is otherwise contraindicated.

Anticoagulation with vitamin K antagonists (warfarin) is advised in patients with previous embolic events, clot in the LA or AF (regardless of the presence of LA clot). Aspirin is not used, as its benefit in stroke prevention is low, with a similar bleeding risk to warfarin. The CHADS or CHADS-VASc score should not be applied to patients with MV disease and AF, as the stroke risk is already high; these patients should be anticoagulated. The new oral anticoagulants have not been tested in this setting and should not be used.

For patients with moderate to severe disease or for those with an episode of acute pulmonary oedema, definitive surgical treatment should be considered and they should be referred for evaluation.

Percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty has superseded surgical valvotomy (closed and open) for patients with pliable valves.[3] This is also the treatment of choice for pregnant MS patients with pliable valves and poor response to medical therapy. Those with calcified, non-pliable valves or significant concomitant mitral regurgitation (MR) are referred for valve replacement surgery.

Mitral regurgitation

MR may be classified depending on the clinical presentation (acute or chronic) or leaflet pathology (functional versus organic).

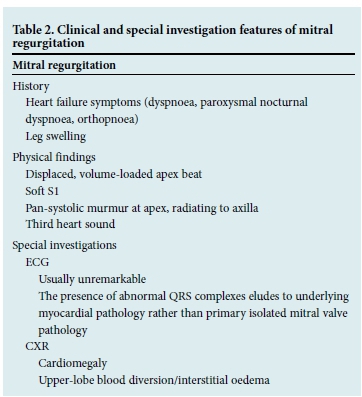

Acute MR is a medical emergency presenting with acute pulmonary oedema and hypotension and is usually caused by endocarditis, myocardial infarction with papillary muscle rupture or spontaneous rupture of the chordae. Afterload reduction with intravenous nitrates or nitroprusside and early surgical intervention is usually required. The clinical and investigational features of chronic MR are summarised in Table 2. Signs of severity include clinical features of heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, a loud murmur grade >3/6 and presence of a third heart sound in the absence of heart failure.

Functional MR is characterised by normal leaflets and is secondary to a dilated and dysfunctional left ventricle. Echocardiography is required to accurately confirm this diagnosis and may differentiate ischaemic from non-ischaemic causes. Functional MR requires optimisation of heart failure therapy, whereas moderate or severe ischaemic MR may require surgery with possible coronary revascularisation.

Organic MR refers to primary leaflet abnormality resulting in MR. The cause is most often rheumatic in South African (SA) patients, whereas degenerative or myxomatous disease is most common in the developed world. Other causes include fibro-elastic disease, congenital (isolated cleft or atrioventricular (AV) canal defect), Marfan syndrome and endocarditis.

Medical therapy has been shown not to be of benefit in MR. Indications for surgery include symptoms, development of AF, pulmonary hypertension, end-systolic diameter >40 mm and ejection fraction <60% on echocardiography. Surgical options include MV replacement or repair, which may mandate earlier surgery, provided a successful durable repair can be obtained.

Aortic stenosis

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common valve lesion in western countries and mainly a disease of the elderly. Common causes of AS include:

- degenerative trileaflet AS

- degenerative bicuspid AS

- rheumatic heart disease - there would usually be concomitant MV

- disease

- other (rare): congenital AS, Pagets disease, end-stage kidney disease, chronic inflammatory diseases.

Haemodynamically significant obstruction usually occurs when the valve area is <1 cm2. Left ventricular hypertrophy develops in response to the progressive obstruction. Risk factors for degenerative AS are similar to those for atherosclerosis, i.e. hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia and smoking.

Patients are asymptomatic for many years. Once symptoms occur, however, there is a rapid decline in life expectancy.'4

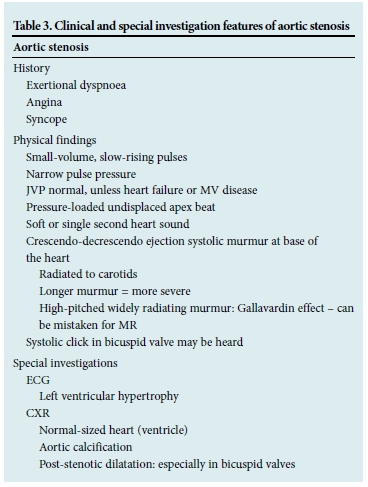

Clinical features of AS are shown in Table 3.

There is no place for medical management of patients with symp- tomatic AS. It is a mechanical obstruction for which the definitive treatment is aortic valve replacement. These patients should therefore all be referred promptly for assessment for valve replacement surgery,[5] which prolongs and improves quality of life, even in octogenarians.[6] For those in whom the risk of surgery is too high, transcatheter aortic valve replacement is currently a possibility.[7]

Aortic regurgitation

Aortic regurgitation may occur as a result of leaflet pathology or secondary to aortic root pathology. Acute regurgitation is poorly tolerated and constitutes a medical and surgical emergency. It is commonly caused by infective endocarditis or aortic root dissection.

Chronic regurgitation is well tolerated and patients are often asymptomatic for many years. Common causes of primary valve lesions are rheumatic heart disease, infective endocarditis, congenital bicuspid valves, and rheumatoid arthritis. Conditions primarily affecting the root, and hence causing regurgitation, are Marfans syndrome, syphilis, sero-negative spondyloarthritides, aortic dis- section and osteogenesis imperfecta.

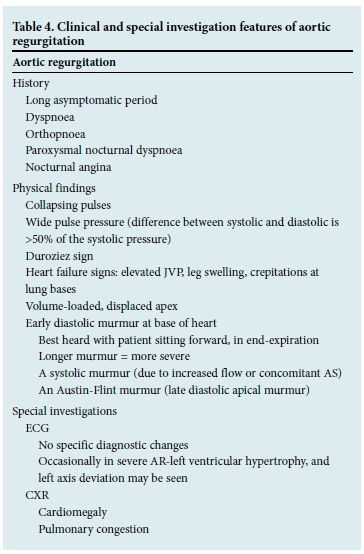

The clinical features are summarised in Table 4. Symptomatic aortic regurgitation requires referral for the assessment for aortic valve replacement. There is no place for medical therapy outside of it being a bridge to surgery or in those too ill for surgery.[2,,8-10]

Tricuspid valve disease

Tricuspid stenosis (TS) is rare and usually rheumatic in origin.[11] Most patients with rheumatic tricuspid valve (TV) disease present with tricuspid regurgitation (TR) or a combination of TR and TS. Isolated rheumatic TS is uncommon, but usually accompanies MV disease. Less common and unusual causes of obstruction to right atrial (RA) emptying include congenital tricuspid atresia, RA tumours, carcinoid syndrome, endomyocardial fibrosis, TV vegetations, pacemaker leads or extracardiac tumours.[11] TS is found at autopsy in 15% of patients with rheumatic heart disease, but is of clinical significance in <5%. As is the case with MS, TS is more common in women. The RA is usually dilated in TS. Clinical and special investigation findings in TS are presented in Table 5.

The most common cause of TR is a dilated right ventricle (RV) and T V annulus ('functional TR').[12] Functional TR may follow on pulmonary hypertension and its causes, RV obstruction (e.g. pulmonary stenosis) or intrinsic RV abnormality (e.g. RV infarction). Rheumatic TR is rare. Non-rheumatic, valvular causes of TR include infective endocarditis, Ebstein anomaly, TV prolapse, carcinoid syndrome, trauma, papillary muscle dysfunction, and connective tissue disease. The clinical and imaging features of TR are listed in Table 5.[11-13]

Prosthetic valves

There are two types of prosthetic valves: mechanical valves and bioprosthetic (tissue) valves. The major differences between the two relate to risk of thromboembolism (higher with mechanical valves) and structural deterioration (higher with bioprostheses).'141 Mechanical valves are classified into three groups: bileaflet, tilting disc and ball- cage. Bileaflet mechanical valves are most commonly implanted. Patients with mechanical valves require long-term anticoagulation. The risk of thromboembolism is about 6 times higher without anticoagulants, and the risk of de novo valve thrombosis is alsohigher. Warfarin is the anticoagulant of choice and the international normalised ratio should be between 2.5 and 3.5. Antiplatelet agents such as aspirin do not provide adequate protection and are not recommended without the use of anticoagulants.

Bioprostheses were developed to overcome the challenges of long-term anticoagulation and increased risk of thromboembolism associated with mechanical valves. A stented tissue valve consists of three tissue leaflets mounted on a ring with semi-rigid stents that facilitate implantation. Because stents add to obstruction and increase stress on the leaflets, stentless tissue valves were developed for the aortic position and are particularly useful for patients with small aortic roots. More recently, a transcatheter bioprosthesis has been developed, which can be implanted via a catheter at the aortic valve position.[15] Homograft aortic valves are harvested from cadavers, sterilised with antibiotics and cryopreserved at -196° for long periods before implantation. Pulmonary autografts (Ross procedure) involve removal of a patient's native pulmonary valve and reimplantation to replace the diseased aortic valve.[15]

Conclusion

The clinical evaluation remains essential in establishing a diagnosis in patients presenting with heart failure due to valvular heart disease. Awaiting results of special investigations should not hinder timeous referral. Those with symptomatic valvular heart disease should be referred promptly for specialist evaluation with a view to definitive surgical correction.

References

1. Sliwa K, Carrington M, Mayosi BM, Zigiriadis E, Mvungi R, Stewart S. Incidence and characteristics of newly diagnosed RHD in urban African adults: Insights from the Heart of Soweto Study. Eur Heart J 2010;31:719-727. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehp530] [ Links ]

2. Braunwald E. Valvular heart disease. In: Braunwald EB, ed. Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: W B Saunders, 1997:1007-1076. [ Links ]

3. Fawzy ME, Shoukri M, Buraiki J, et al. Seventeen years' clinical and echocardiography follow-up of mitral balloon valvuloplasty in 520 patients, and predictors of long term outcome. J Heart Valve Dis 2007; 16:454-460. [ Links ]

4. Rosenhek R, Zilberszac R, Schemper M, et al. Natural history of very severe aortic stenosis. Circulation 2010;121:151-156. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.894170] [ Links ]

5. Rahimtoola SH. Indications for surgery in aortic valve disease. In: Yusuf S, Cairns JA, Camm AJ, eds. Evidence Based Cardiology. London: BMJ Books, 1998:811-832. [ Links ]

6. Chukwuemeka A, Borger MA, Ivanov J, Armstrong S, Feindel CM, David TE. Valve surgery in octogenarians: A safe option with good medium-term results. J Heart Valve Dis 2006;15:191-196. [ Links ]

7. Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al. PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo surgery. N Engl J Med 2010;363:1597- 1607. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1008232] [ Links ]

8. Vehanian A, Ottavio A, Andreotti F, et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2451-2496. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehs109] [ Links ]

9. Nishimura R, Otto C, Bono RO, et al. 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients with Valvular Heart Disease - a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014;63(22):e57-e185. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.02.536] [ Links ]

10. Cupido B, Commerford PJ. Valvular heart disease. In: Rosendorff C, ed. Essential Cardiology. 3rd ed. New York: Springer, 2013. [ Links ]

11. Bruce CJ, Connolly HM. Right-sided valve disease deserves a little more respect. Circulation 2009;119(20):2726-2734. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.776021] [ Links ]

12. Rogers JH, Bolling SF. The tricuspid valve: Current perspective and evolving management of tricuspid regurgitation. Circulation 2009;119(20):2718-2725. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.842773] [ Links ]

13. Forfia PR, Wiegers SE. In: Otto CM, ed. The Clinical Practice of Echocardiography. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier, 2007:848-876. [ Links ]

14. Pibarot P, Dumesnil JG. Prosthetic heart valves: Selection of the optimal prosthesis and long-term management. Circulation 2009;119(7):1034-1048. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.778886] [ Links ]

15. O'Gara PT, Bonow RO, Otto CM. In: Otto CM, Bonow RO, eds. Valvular Heart Disease: A Companion to Braunwald's Heart Disease. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier, 2009:383-398. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

B J Cupido

bj.cupido@uct.ac.za