Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.105 no.11 Pretoria Nov. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2015.V105I11.10099

CONTINUING MEDICAL EDUCATION

ARTICLE

Understanding and responding to HIV risk in young South African women: Clinical perspectives

R DellarI, II; A WaxmanIII; Q Abdool KarimIV, V

IMBiochem Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry (Oxon); Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA), University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IIMBiochem Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry (Oxon); Africa Centre for Health and Population Studies, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IIIMSc Public Health in Developing Countries; Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA), University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IVPhD (Medicine); Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA), University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

VPhD (Medicine);Mailman School of Public Health, Columbia University, New York, USA

ABSTRACT

Young women (15 - 24 years) contribute a disproportionate 24% to all new HIV infections in South Africa - more than four times that of their male peers. HIV risk in young women is driven by amplifying cycles of social, behavioural and biological vulnerability. Those most likely to acquire infection are typically from socioeconomically deprived households in high HIV-prevalence communities, have limited or no schooling, engage in transactional sex or other high-risk coping behaviours, and have a history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and/or pregnancy. Despite the imperative to prevent HIV acquisition in young women, there is a dearth of evidence-based interventions to do so. However, there are several steps that healthcare workers can take to improve outcomes for this key population at the individual level. These include being able to identify high HIV-risk young women, ensuring that they receive the maximum social support they are eligible for, providing reliable and non-judgemental counselling on sexual and reproductive health and relationships, delivering contraceptives and screening and treating STIs in the context of accessible, youth-friendly services.

Despite huge improvements in access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) and an overall decline in HIV incidence in South Africa (SA), young women (15 - 24 years) remain uniquely vulnerable to infection. They contribute about a quarter of all new HIV infections occurring in SA and are thus key to epidemic control. Understanding and responding to the risk they face is a public health imperative.

Many studies have sought to characterise factors associated with higher vulnerability to HIV in young women. Together, these studies paint a picture of an amplifying cycle of risk for many young South Africans. Typically, this cycle is founded in poor socioeconomic backgrounds that drive engagement in high-risk sexual behaviours and expose young women to risks of sexual abuse, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and pregnancy. Directly and indirectly, all these experiences have substantial implications for the odds of young women acquiring HIV. Those at greatest risk can be identified and prioritised by healthcare workers as being from unstable or child-headed households, not being in school, engaging in transactional sex, being victims of gender-based violence and/or having a history of pregnancy or STIs.

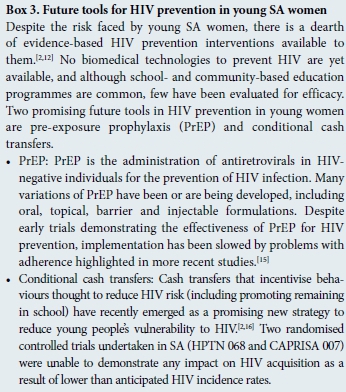

Despite the current lack of biological technologies available to reduce HIV acquisition risk in young women, healthcare workers may have a substantive impact on young women's lives at the individual level by helping them to break out of the cycles of vulnerability they face. Ensuring that young people receive the full available social and financial support they are eligible for via governmental and non-governmental organisations is an important first step, especially considering the many structural factors that drive high-risk behaviours in this key population. Healthcare workers can also provide reliable information on sexual and reproductive health. Importantly, such counselling should be tailored to the individual recipient and aim to include discussions about healthy relationships and female genital cleaning practices in addition to the more standard risk-reduction curriculum. Providing access to STI screening, STI treatment, and family planning services is key.

Critical to all these healthcare worker-initiated strategies is an environment in which young people feel comfortable: a non-judgemental, non-stigmatising, confidential service. Clinics in high HIV-prevalence areas might consider developing specially trained youth-friendly teams that serve clinics at specific hours suited to young people. Furthermore, in rural communities, mobile treatment and education services could reach more isolated young women.

Healthcare worker cognizance of the real-life context of the lives of young women is vital to assisting them in reducing their HIV risk and supporting the public health goals of epidemic control.

Why is it important to address HIV risk in SA's young women?

Preventing new HIV infections in adolescent girls and young SA women is a public health imperative. This key population has an unprecedentedly high risk of acquiring HIV. In 2012, it was estimated that 1 young SA woman (15 - 24 years) was infected every 5 minutes.[1] Further, given that a quarter of all new infections in SA occur in young women, the goals of an 'AIDS-free generation' will not be achieved without reducing their risk of HIV acquisition.[1]

What do we know about what contributes to HIV risk in young people?

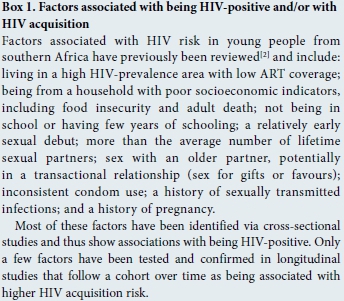

A large number of studies have sought to characterise social, behavioural and biological factors associated with HIV risk in young women (Box 1). The factors fall into several broad categories that describe a network of inter-related risk (Fig. 1).

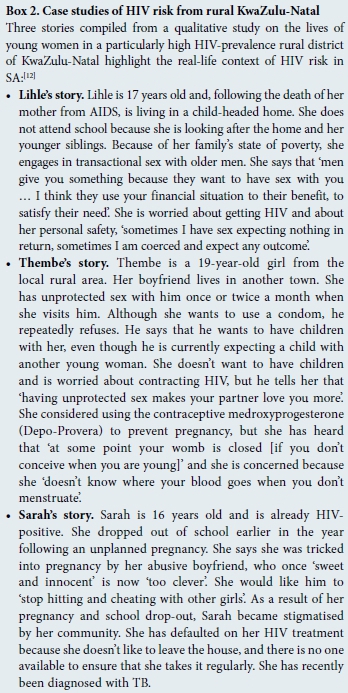

At a structural level, young women at greatest risk of HIV acquisition are those from socioeconomically deprived communities with high levels of unemployment, high background HIV prevalence, and poor access to ART programmes.[13] In these communities, the most vulnerable households include those with histories of premature adult deaths (often AIDS related), typically with a degree of food insecurity. Young women from child-headed households are at particular risk (Box 2: Lihle's story).[4]

Young women from poor socioeconomic backgrounds are more likely to have few years of schooling, leading to poor knowledge of sexual and reproductive processes and services available to them (Box 2: Thembe's story).[4] Furthermore, young women living in such settings may also engage in high-risk behaviours to either relieve immediate survival challenges or because of a limited sense of a potential better future.[5,6] These behaviours may include early sexual debut and engagement in transactional sex (sex for gifts or favours, rather than formal prostitution), often with older partners with higher HIV prevalence than their peers (Box 2: Sarah's story).[7,8] Young women experiencing gender-based violence are also at high risk of HIV acquisition, as negotiating condom use in such relationships is especially difficult.[9]

If engagement in high-risk behaviours does not directly result in HIV infection, it often leads to other poor sexual and reproductive health outcomes that compound risk. Herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2), human papillomavirus (HPV) and other STIs can all leave women biologically more susceptible to HIV for every exposure they have.[10] Certain female genital cleansing practices (including douching and insertion of foreign substances) may also mediate risk via inflammation.[11] Moreover, engaging in unprotected sex carries a risk of pregnancy, which can lead to stigmatisation and school drop-out, and may amplify the risks of gender-based violence or engagement in transactional sex owing to vulnerability and material need, respectively (Box 2: Sarah's story).

What tools do healthcare workers have to reduce the risk of young people becoming infected with HIV?

Given the current lack of availability of effective biomedical HIV prevention technologies[2,12] and the importance of structural factors in driving HIV in young SA women, it might seem that there is not much healthcare workers can do to support the former in reducing their odds of acquiring HIV, except advocate for broader economic and scientific development (Box 3). However, a closer look at the case studies in Box 2 reveals a number of ways in which healthcare workers might intervene to break young women out of the cycles of amplifying risk they face.

The first action in helping to reduce the vulnerability of their young female patients is confirming that those in severe financial need, or from child-headed households, receive the full governmental support (both financial and social) available to them. In some cases, referral to local non-governmental organisations for additional aid may also be an option. Ensuring that young women such as Lihle receive adequate support is essential in preventing them feeling forced into engaging in transactional sex or other high-risk behaviours for immediate survival.

A second action that healthcare workers can take is to provide reliable and non-judgemental counselling on sexual and reproductive health. Although such counselling is usually available, lack of healthcare worker expertise or time often means that key risk factors are not adequately addressed. For example, if Thembe was given complete information on fertility control, she might have chosen to initiate hormonal contraceptives, thereby reducing her pregnancy risk, avoiding dropping out of school, and ultimately reducing her HIV risk. Counselling with regard to condom use should be included, but healthcare workers should be aware that young women often have limited say in this decision. If couple counselling or engaging with a male partner is not possible, counselling should extend to relationships and negotiating advice on safer sexual matters. Another important extension of counselling that is currently rarely performed is the discussion of inappropriate vaginal cleaning practices that may increase susceptibility to HIV.

A third intervention point in the cycles of HIV risk faced by young women is the treatment of STIs other than HIV. Treating HSV-2 and other STIs is critical to ensure that young people's HIV exposure risk is reduced. Therefore, all young people attending clinics should be screened for STIs, even if this is not the primary purpose of their visit.

Prerequisites to all of these interventions is the provision of accessible services prioritised for the most HIV-vulnerable young women. All healthcare workers should be able to identify young people at highest HIV risk (using the above associations as guiding points) and have an obligation to ensure that they are providing non-stigmatising and completely confidential services. Furthermore, clinics in high-risk areas might consider the additional provision of mobile youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health education programmes and services to reach those without access to or not utilising fixed healthcare facilities.[14]

Conclusions

Understanding and responding to the unprecedented levels of HIV risk in young SA women is a public health imperative for continued progress towards control of the HIV epidemic. Healthcare workers have a vital role to play in reducing this risk, as they have the opportunity to make substantial changes to young women's lives at the individual level. Maximising this benefit requires healthcare workers to be able to understand the complexity of what drives vulnerability to HIV in young women so that they can identify women who require special attention, such as those from child-headed households, those not in school, and those engaging in transactional sex. Understanding the drivers of HIV is also critical in developing appropriate intervention strategies to break down cycles of risk. At the core of these healthcare worker-initiated intervention strategies is ensuring that vulnerable young people have access to the social support available to them, receive reliable, extensive and non-judgemental counselling, and are regularly screened for STIs. Developing youth-friendly services tailored to meet the unique sexual and reproductive health needs of young people is also critical.

Acknowledgements. Rachael Dellar was previously supported by the CAPRISA Fellowship Training Programme and is currently funded by an MRC Flagship Grant (MRC-RFA-UFSP-01-2013/UKZN HIVEPI). Aliza Waxman was a CAPRISA trainee supported by a Fogarty Fullbright Scholarship. The case studies in Box 2 were compiled from a series of interviews with young women, undertaken as part of a larger qualitative research study (approved by the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (HSS REC/0019/014)).

References

1. Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC. South African National HIV Prevalence Incidence and Behaviour Survey 2012. Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2014. [ Links ]

2. Dellar RC, Dlamini S, Karim QA. Adolescent girls and young women: Key populations for HIV epidemic control. J Int AIDS Soc 2015;18(2 Suppl 1):19408. [http://dx.doi.org/10.7448/ias.18.2.19408] [ Links ]

3. Pettifor AE, Rees HV, Kleinschmidt I, et al. Young people's sexual health in South Africa: HIV prevalence and sexual behaviors from a nationally representative household survey. AIDS 2005;19(14):1525-1534. [ Links ]

4. Hallman K. Gendered socioeconomic conditions and HIV risk behaviours among young people in South Africa. Afr J AIDS Res 2005;4:37-50. [http://dx.doi.org/10.2989/16085900509490340] [ Links ]

5. Chatterji M, Murray N, London D, Anglewicz P. The factors influencing transactional sex among young men and women in 12 sub-Saharan African countries. Soc Biol 2005;52(1-2):56-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19485565.2002.9989099] [ Links ]

6. Weiser SD, Leiter K, Bangsberg DR, et al. Food insufficiency is associated with high-risk sexual behavior among women in Botswana and Swaziland. PLoS Med 2007;4(10):1589-1597; discussion 1598. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040260] [ Links ]

7. Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Gray GE, McIntryre JA, Harlow SD. Transactional sex among women in Soweto South Africa: Prevalence risk factors and association with HIV infection. Soc Sci Med 2004;59(8):1581-1592. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.003] [ Links ]

8. Stoebenau K, Nixon SA, Rubincam C, et al. More than just talk: The framing of transactional sex and its implications for vulnerability to HIV in Lesotho, Madagascar and South Africa. Global Health 2011;7:34. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1744-8603-7-34] [ Links ]

9. Pettifor AE, Measham DM, Rees HV, Padian NS. Sexual power and HIV risk South Africa. Emerg Infect Dis 2004;10(11):1996-2004. [http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid1011.040252] [ Links ]

10. Cohen MS. HIV and sexually transmitted diseases: Lethal synergy. Top HIV Med 2004;12(4):104-107. [ Links ]

11. McClelland RS, Lavreys L, Hassan WM, Mandaliya K, Ndinya-Achola JO, Baeten JM. Vaginal washing and increased risk of HIV-1 acquisition among African women: A 10-year prospective study. AIDS 2006;20(2):269-273. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.aids.0000196165.48518.7b] [ Links ]

12. Waxman A, Humphries H, Frohlich J, et al. Young women's life experiences and perceptions of sexual and reproductive health in rural KwaZulu-Natal South Africa (in preparation). [ Links ]

13. Mavedzenge SN, Luecke E, Ross DA. Effectiveness of HIV Prevention Treatment and Care Interventions Among Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. UNICEF Technical Brief. New York: UNICEF, 2013. [ Links ]

14. Denno DM, Chandra-Mouli V, Osman M. Reaching youth with out-of-facility HIV and reproductive health services: A systematic review. J Adolesc Health 2012;51(2):106-121. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.01.004] [ Links ]

15. Bekker L-G, Gill K, Wallace M. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for South African adolescents: What evidence? S Afr Med J 2015;105(11):907-911. [http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2015.v105i11.10222] [ Links ]

16. Pettifor A, MacPhail C, Nguyen N, Rosenberg M. Can money prevent the spread of HIV? A review of cash payments for HIV prevention. AIDS Behav 2012;16(7):1729-1738. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10461-012-0240-z] [ Links ]

Continuing medical education resources

Dellar RC, Dlamini S, Abdool Karim Q. Adolescent girls and young women: Key populations for HIV epidemic control. J Int AIDS Soc 2015;8(2 Suppl 1):19408. [ Links ]

Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence and Behaviour Survey, 2012. Cape Town: HSRC Press, 2014. http://www.hsrc.ac.za/uploads/pageContent/4565/SABSSM%20IV%20LEO%20finaLpdf (accessed 23 September 2015). [ Links ]

UNICEF Technical Brief. Effectiveness of HIV Prevention, Treatment and Care Interventions Among Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. UNICEF: New York, 2013. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

R Dellar

rachael.dellar@gmail.com