Serviços Personalizados

Artigo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares em Google

Similares em Google

Compartilhar

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versão On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versão impressa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.105 no.11 Pretoria Nov. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2015.V105I11.10126

REVIEW

Improving adolescent maternal health

C BaxterI; D MoodleyI, II

IPhD; Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA), University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

IIPhD; Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Health Sciences, Nelson R Mandela School of Medicine, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

ABSTRACT

Each year thousands of adolescent girls and young women in South Africa (SA) become pregnant and many die from complications related to pregnancy and childbirth. Although women of all ages are susceptible, girls <15 years of age are five times as likely, and those aged 15 - 19 years twice as likely, to die from complications related to childbirth than women in their 20s. In SA, non-pregnancy-related infections (e.g. HIV), obstetric haemorrhage and hypertension contributed to almost 70% of avoidable maternal deaths. In addition to the implementation of standardised preventive interventions to reduce obstetric haemorrhage and hypertension, better reproductive health services for adolescents, access to HIV care and treatment for women infected with HIV, and improved access to and uptake of long-acting reversible contraception are important ingredients for reducing maternal mortality among adolescents.

Each year, >200 million women worldwide become pregnant, with almost 90% of the pregnancies occurring in developing countries. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that about 16 million young women aged 15 - 19 years and 1 million girls <15 years of age give birth each year, accounting for about 11% of all births worldwide. Although the number of adolescent girls aged 15 - 19 giving birth has declined globally between 1990 and 2011, the decrease in sub-Saharan Africa is marginal -decreasing from 123 births/1 000 girls in 1990 to 117 births/1 000 girls in 2011.[1] The majority of young women become sexually active during early adolescence and many before marriage. In sub-Saharan Africa, about 60% of young women are sexually active by the age of18 years and many women living in developing countries give birth to their first child before that age. In South Africa (SA), >30% of 19-year-olds report having given birth at least once and many of these young women have not yet completed their secondary education when they become pregnant.[2]

Global estimates and causes of maternal mortality

Although the number of women dying from complications related to pregnancy and child-bearing has declined by 45% between 1990 and 2013,[1] maternal mortality remains unacceptably high. In 2013, an estimated 289 000 women died globally during and after pregnancy and childbirth. Almost all of the maternal deaths (99%) occurred in developing countries - over two-thirds in sub-Saharan Africa.[1]

A systematic analysis of the causes of maternal mortality between 2003 and 2009 shows that the ma'ority of maternal deaths are due to severe bleeding (27.1%), hypertensive disorders (14%), sepsis (10.7%) and unsafe abortions (7.9%).

Maternal mortality among adolescents

Although complications related to pregnancy and childbirth may occur in women of all ages, adolescent girls <15 years face a particularly high risk of maternal mortality. According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), girls <15 years are five times as likely, and those aged 15 - 19 twice as likely, to die from complications related to childbirth than women in their 20s. A study of 854 377 Latin American women shows that young girls <15 years had a higher risk of maternal death, early neonatal death and anaemia compared with women aged 20 - 24 years.[3] In SA, adolescents are at a significantly increased risk of dying owing to complications of hypertension in pregnancy.[4] Compared with women aged 20 - 24 years, adolescents also experience an increased risk of premature labour and giving birth to low-birth-weight infants. A systematic analysis of population health data shows complications in pregnancy and childbirth to be leading causes of death among adolescent girls in developing countries.[5]

The incomplete physical development of a young girl's body, high rates of unintended pregnancy among young girls, and their lack of information concerning their bodies and preparation with regard to pregnancy and childbirth all contribute to an increased risk of maternal mortality. Unmarried pregnant teenagers often encounter societal disapproval and report stress and instability in their relationships with their families and partners. Young adolescents are sometimes discouraged from seeking appropriate care during pregnancy because of negative health service provider attitudes, or face other obstacles in accessing services (e.g. inconvenient locations or operating hours and/or insufficient funds to pay for services or transport).

For these and other reasons, young women are less likely to access care during pregnancy than older women and more likely to seek abortions, particularly if the pregnancy is unintended. In 2008, there were an estimated 86 million unintended pregnancies worldwide,[6] 48% of which were terminated through abortions, often under unsafe conditions. Young women aged 15 - 19 years accounted for about 3.2 million (15%) of unsafe abortions performed worldwide. Unsafe abortions are estimated to cause 70 000 maternal deaths each year, and result in serious complications that require medical treatment in a further 8 million women.[7] Although abortion has been legal in SA since 1997, and can be obtained by any woman of any age if she is <13 weeks pregnant, many women still obtain abortions unsafely.

In addition to the health risks to the young mother and her child, pregnancy during adolescence can negatively impact on a young woman's opportunities for education. Young women who become pregnant while at school often drop out and only a few return after childbirth. One study in KwaZulu-Natal shows that only about 30% of adolescents aged 14 - 19 and half of young women aged 20 - 24 who had dropped out of school because of pregnancy returned to school.[8' Although SA law allows pregnant girls to remain in school and return to school after childbirth, those with family support and/or financial support are more likely to return to school after childbirth.

Adolescent pregnancy and antenatal care

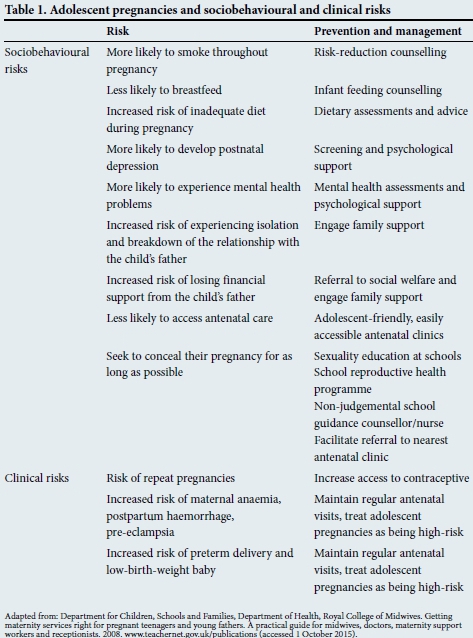

Most maternal deaths are considered preventable because the management and prevention of complications that lead to such deaths are well known. A report on confidential enquiries into maternal deaths in SA shows that non-pregnancy-related infections (e.g. HIV), obstetric haemorrhage and hypertension contributed to 67% of avoidable deaths during 2011 - 2012.[4] In SA, maternity care is a vital component of primary healthcare and standardised guidelines have been developed for the management of preg-nancies.[9] Antenatal care for adolescents in SA is not particularly different from that available to older women. While antenatal attendance may be substandard for all women, adolescents are more likely to access antenatal services late in pregnancy or not at all. The lack of antenatal care contributes to pregnancy complications and adverse birth outcomes associated with adolescent pregnancies. In addition to the implementation of recommended preventive interventions to reduce obstetric haemorrhage (e.g. community education, prevention of prolonged labour, prevention of anaemia, use of safe methods for induction of labour and active management of the third stage of labour)[9] and hypertension (e.g. calcium supplementation during antenatal care, and detection, early referral and timely delivery of women with hypertension),[9] many other clinical and sociobehavioural challenges faced by adolescents in pregnancy can be addressed at a primary healthcare level (Table 1).

Screening for HIV and linkage to appropriate care, treatment and prevention

In sub-Saharan Africa, young women are disproportionately affected and acquire HIV infection about 5 years earlier than men.[10]A national survey conducted in SA in 2012 shows that HIV prevalence among 15 - 19-year-old women was 5.6% compared with 0.7% in young men of the same age. In the same year, the SA Department of Health estimated that HIV prevalence among pregnant 15 - 19-year-olds was 12.4%. Therefore, adolescents and young women in SA who engage in unprotected sex leading to pregnancy are at a particularly high risk of acquiring HIV Reducing HIV infection among this vulnerable population is critical, and the strengthening of HIV services for pregnant women is an urgent priority.

All maternity health facilities should encourage young women to know their HIV status by offering counselling and testing. Testing adolescents for HIV is an important opportunity to engage with and link them to essential HIV treatment, care and prevention interventions. HIV prevention tools, including repeated counselling and testing (every 6 months), provision of condoms, and post-exposure prophylaxis should be made available for all HIV-negative women. An SA study examining barriers to HIV testing uptake and participation in prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) among adolescent mothers revealed that healthcare worker-client interactions, early premarital pregnancy stigma, lack of confidentiality and poor treatment by healthcare workers strongly influenced adherence to the PMTCT protocol.[11]

An increasing number of children who were infected with HIV perinatally are surviving into adolescence. Therefore, some of the adolescents who are HIV-positive may have acquired HIV vertically through MTCT, while others would have acquired HIV horizontally through sex or drug use. Young women who acquired HIV perinatally and are already on antiretroviral treatment (ART) should be monitored for long-term ART toxicities and virological failure, and managed according to national guidelines.[12] Young women who are not yet on ART should be linked to and provided with treatment according to current ART guidelines, with appropriate dose and regimen adjustments for adolescents. The current SA national guidelines recommend immediate initiation with lifelong ART in pregnant women.[12]

Pregnant women who are HIV-positive should also be screened for tuberculosis and offered information on the availability of PMTCT interventions, including counselling on safe infant feeding choices. Young women should be counselled about disclosing their HIV status to others and be empowered and supported to determine if, when, how and to whom to disclose.[12] Adolescents require much support from healthcare providers, peers and their community to disclose safely and confidently, and to be able to cope with any negative reactions from their family, friends and community. National guidelines for the management of HIV recommend that adolescents should be allowed and encouraged to invite an adult or a friend to be present to support them.[12]

One ofthe major challenges that HIV-positive adolescents face is adherence to treatment. One SA study showed that adolescents were significantly less likely to adhere to ART and had lower rates of virological suppression than adults. Therefore, healthcare providers need to support adolescents in finding strategies to overcome adherence challenges.

Postnatal care and support for adolescents

Given that most SA women return to the clinic postnatally and bring their infants for scheduled immunisation visits, these encounters are important for reducing morbidity and mortality among adolescents and their newborns. These opportunities are important for preventing, diagnosing and treating medical complications in the first few weeks after delivery and promoting HIV prevention and contraceptive services to prevent further unwanted or unplanned pregnancies. The postpartum visits should also focus on counselling on baby care, promotion and support of breastfeeding, nutritional advice, and immunisation.

Prevention of unintended and unwanted pregnancies

Provision of contraception is an important tool for the prevention of unwanted and/or unplanned pregnancies and ultimately the prevention of maternal deaths. All women, including adolescents, need access to contraception and safe abortion services, if that is their choice.

Although the worldwide use of contraception has increased significantly between 1990 and 2012, the unmet need for family planning is still high, estimated to be 25% in sub-Saharan Africa.[13] Although making contraception more accessible would reduce the rate of unintended pregnancies, it is also essential that contraception be used consistently, correctly and effectively. A number of safe and effective contraceptive options are available. Long-acting reversible contraception options that are recommended for adolescents include:

- Intrauterine devices, which can last up to 5 years.

- Progestogen-only injectables such as Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) (Depot-Provera), which is administered once every 12 weeks, and norethisterone enanthate (NET-EN), which is administered once every 8 weeks. Although controversial, a meta-analysis of observational studies in sub-Saharan Africa has suggested that DMPA may be associated with increased HIV risk, particularly in younger women.[14] Although more evidence is needed to empirically confirm this association, women who may be at risk for HIV should be counselled to also use condoms if they insist on using DMPA for contraception.

- Subdermal progestogen implants that provide protection for 3 - 5 years.

Long-acting reversible methods are preferred for adolescents because these are less reliant on compliance or correct and consistent use. Other options that could be considered for adolescents but are dependent on compliance include:

- Oral contraceptive (OC) pills. If taken consistently and correctly, contraceptive pills, such as low-dose combined oral contraceptive (COC) pills and progestogen-only pills (POPs), are highly effective. Oral contraceptives that contain cyproterone acetate or drospirenone also provide the added benefit of treating acne, making them an attractive option for some adolescents. However, non-adherence and 'pill failure' are common among OC users.

- Emergency contraception. Two types of safe and effective emergency contraceptive methods are currently available in SA: (i) hormonal emergency contraceptive pills, particularly POPs, taken within 5 days of unprotected intercourse; and (ii) the insertion of a copper intrauterine device by a health professional up to 5 days after unprotected intercourse. When emergency contraception is requested, it is an important opportunity to provide counselling about the future use of regular contraception and the prevention of unintended pregnancies.

- Male and female condoms, when used correctly and consistently, are highly effective in preventing both pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. However, correct and consistent use is difficult to achieve and many men and women have a negative attitude towards condoms. Regardless of the challenges, use of condoms should always be promoted, with an emphasis on consistent and proper use.

Improvement in health systems to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality among adolescents

To overcome barriers to care among adolescents, services for them could be made more 'youth friendly'. Healthcare providers need to use a counselling approach that is non-'udgemental and develop skills and techniques that welcome adolescent clients to their clinics and encourage them to seek care. Health facilities management are encouraged to maintain the eight standards, developed by the WHO, to improve quality of healthcare services for adolescents[15] - services that are equitable, accessible, acceptable, appropriate and effective (Table 2).

References

1. United Nations (UN). The Millennium Development Goals Report 2014. New York: UN, 2014. [ Links ]

2. Kaufman CE, de Wet T, Stadler J. Adolescent pregnancy and parenthood in South Africa. Studies in Family Planning 2001;32(2):147-160.[http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2001.00147.x] [ Links ]

3. Conde-Agudelo A, Belizán JM, Lammers C. Maternal-perinatal morbidity and mortality associated with adolescent pregnancy in Latin America: Cross-sectional study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005;192(2):342-349. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2004.10.593] [ Links ]

4. Pattinson R, Fawcus S, Moodley J, National Committee for Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths. Saving Mothers 2011 - 2012: Tenth Interim Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in South Africa. Pretoria: National Department of Health, 2014. [ Links ]

5. Patton GC, Coffey C, Sawyer SM, et al. Global patterns of mortality in young people: A systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet 2009;374(9693):881-892. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60741-8] [ Links ]

6. Singh S, Sedgh G, Hussain R. Unintended pregnancy: Worldwide levels, trends, and outcomes. Studies in Family Planning 2010;41(4):241-250. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/'.1728-4465.2010.00250.x] [ Links ]

7. Singh S, Wulf R, Hussain R, Bankole A, Sedgh G. Abortion Worldwide: A Decade of Uneven Progress. New York: The Guttmacher Institute, 2009. [ Links ]

8. Grant MJ, Hallman KK. Pregnancy-related school dropout and prior school performance in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Studies in Family Planning 2008;39(4):369-382. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.00181.x] [ Links ]

9. Department of Health. Guidelines for maternity care in South Africa: A manual for clinics, community health centres and district hospitals. http://www.rmchsa.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Maternal-Care-Guidelines-2015_FINAL-15.6.15.pdf (accessed 26 August 2015). [ Links ]

10. UNAIDS. The Gap Report. 2014. http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2014/20140716_UNAIDS_gap_report (accessed 29 September 2015). [ Links ]

11. Varga C, Brookes H. Factors influencing teen mothers' enrollment and participation in prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission services in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Qual Health Res 2008;18(6):786-802. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1049732308318449] [ Links ]

12. Department of Health. National Consolidated Guidelines for the Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the Management of HIV in Children, Adolescents and Adults. Pretoria: National Department of Health, 2014. [ Links ]

13. Sedgh G, Hussain R, Bankole A, Singh S. Women with an Unmet Need for Contraception in Developing Countries and Their Reasons for Not Using a Method. New York: The Guttmacher Institute, 2007. [ Links ]

14. Morrison CS, Chen PL, Kwok C, et al. Hormonal contraception and the risk of HIV acquisition: An individual participant data meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2015;12(1):e1001778. [http://dx.doiorg/10.1371/joumalpmed.1001778] [ Links ]

15. Nair M, Baltag V, Bose K, Boschi-Pinto C, Lambrechts T, Mathai M. Improving the quality of health care services for adolescents, globally: A standards-driven approach. J Adolesc Health 2015;57(3):288-298. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.05.011] [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

C Baxter

cheryl.baxter@caprisa.org