Servicios Personalizados

Articulo

Indicadores

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

versión On-line ISSN 2078-5135

versión impresa ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.105 no.7 Pretoria jul. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJNEW.7817

CORRESPONDENCE

William Guybon Atherstone: His 8-day and 1 600 km house call to Oudtshoorn in 1890

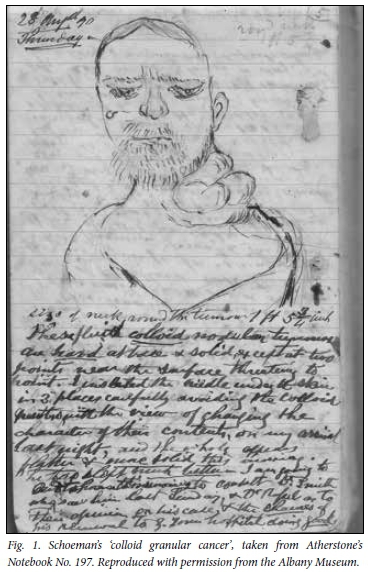

To the Editor: William Guybon Atherstone (1814 - 1898) became well known because for six decades he and his father, John Atherstone, practised medicine in Grahamstown in the Eastern Cape during the turbulent Frontier Wars. When not attending patients, he pursued his interests in geology and botany. He is best known for having performed the first successful surgical procedure under general ether anaesthetic,[1] and for having identified the first diamond found in the Cape Colony.[2] I describe the professional visit of Atherstone to attend a patient with a tumour of the lip and mass in the neck. On 25 August 1890 Atherstone received a telegram from Johannes Hendrik Schoeman asking him to visit because his own doctor was 'dangerously ill'; Atherstone took the 20h05 train to Prince Albert Road Station, arriving at 23h30 the next day, and then travelled by horse and cart to Prince Albert and over the Swartberg Pass, arriving at Schoemanshoek, Schoeman's residence near Oudtshoorn, at 17h30 on 27 August - a trip of 800 km and 45½ hours. He took a history, and examined Schoeman and recorded:

'... I diagnosed the case as one of colloid glandular cancer from a pipe. I measured round Schoeman's neck over the lobular tumour -one foot five and a half inches [44.5 cm] from the inside of the tumour, over the large colloid projection six and three quarter inches [17.2 cm] across and three and three quarter inches [9.5 cm] across and three and three quarter inches [9.5 cm] vertically!

'History - two years previously a dry scaly pimple appeared on the lower lip near the angle of the mouth; in six or eight days the crust came off, and then formed again and became like a moist wart for eight to ten months. It would not heal. Dr. Russell burnt it with "No. 5" - it stank because of the discharge. Twice more he burnt it, and it became a sore which he excised together with a wart on the chin. It then healed, but the left gland was slightly swollen; a lump appeared on the left side of the neck, about the size of a walnut and grew steadily.

'Mr. Schoeman had always been strong, active and healthy until the sore appeared on his lip where he had been accustomed to hold his pipe. He had not however smoked a pipe for a very long time, only the occasional cigar, but confessed that the cigar was also put on the left side, where the pipe had been and where the sore was.'

In keeping with professional ethics, Atherstone then travelled a further 15 km into Oudtshoorn to discuss the patient with Drs George Russell and Herbert Urmson Smith.

On 2 October 1890, Atherstone admitted Schoeman to Albany Hospital in the care of the Visiting Surgeon John Baldwin Smithson Greathead. Two weeks later, against medical advice, Schoeman discharged himself, returned home, and died on 28 October 1890 aged 53 years.[3]

Atherstone kept records of his activities in about 200 notebooks (Fig. 1), which are kept in the Albany Museum in Grahamstown. They have been published in a somewhat disorganised 'pseudoautobiography' in which it is impossible to distinguish between Atherstone's words and those of his autobiographer.[4]

Schoeman almost certainly suffered from an infected squamous cell carcinoma of the lip that had metastasised to the left cervical lymph nodes.[5] Atherstone knew of its association with pipe smoking, as described in the 18th century,[6] and would have been aware of its detailed description more widely published in the mid-19th century.[7]

There is no explanation for Schoeman's summoning Atherstone, rather than a doctor from Cape Town. Perhaps he had impressed the Schoeman family when shown the Cango Caves by Carel Schoeman, the patient's uncle, in December 1852;[8] also, by 1890 Atherstone had become well known in the Cape Colony, having been elected Member of the Legislative Assembly for Grahamstown in 1881, when he may have retired from medical practice.[9-11]

Acknowledgements. Dr Elizabeth van Heyningen brought my attention to Atherstone's notebooks and pseudoautobiography. Ms Amy van Wezel of the Albany Museum scanned and supplied Fig. 1.

S A Craven

Department of Family Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa sacraven@mweb.co.za

References

1. Sulphuric ether. Graham's Town Journal 26 June 1847, p. 3. [ Links ]

2. Metrowich FC. William Guybon Atherstone. In: De Kock WJ, ed. Dictionary of South African Biography, Vol. I. National Council for Social Research, 1968:25-27. [ Links ]

3. Mathie N. Man of many facets Atherstone Dr WG 1814-1898. Vol. 2. 1997:466-468. 4. Mathie N. Man of many facets Atherstone Dr WG 1814-1898. 1997:1-1106. [ Links ]

5. Maruccia M, Onesti MG, Parisi P, Cigna E, Troccola A, Scuderi N. Lip cancer: A 10-year retrospective epidemiological study. Anticancer Research 2012;32(4):1543-1548. [ Links ]

6. Friderico DN. Carcinoma labii inferioris absque sectione persanatum. Dissertation 16 pp., Rintelii. 1737. http://digital.slub-dresden.de/werkansicht/d]f/5964/9/ (accessed 31 January 2015). [ Links ]

7. Bouisson DÉF. Du cancer buccal chez les fimeurs. Montpellier Medical 1839;1(2):539-559;1(3):19-41. [ Links ]

8. Mathie N. Man of many facets Atherstone Dr WG 1814-1898. Vol. 1. 1997:70-74. [ Links ]

9. Burrows EH. A History of Medicine in South Africa. Cape Town: Balkema, 1958:168-177. [ Links ]

10. Laidler PW, Gelfand M. South Africa: Its Medical History 1652-1898. Cape Town: Struik, 1971:168, 250, 281-283, 294, 332-334, 346-347, 353, 433, 498. [ Links ]

11. Deacon H, Phillips H, van Heyningen E. The Cape Doctor in the Nineteenth Century: A Social History. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2004:34-35, 175, 176, 180-181, 256 . [ Links ]

12. Cape Archives MOOC 13/1/609 49. [ Links ]