Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.105 n.6 Pretoria Jun. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.8705

RESEARCH

Prehospital cooling of severe burns: Experience of the Emergency Department at Edendale Hospital, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

D FiandeiroI; J GovindsamyII; R C MaharajIII

IMB ChB, FCEM (SA), Dip EC (SA), DA (SA); Department of Emergency Medicine, Edendale Hospital, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

IIMB ChB, DA (SA); Burns Unit, Department of Surgery, Edendale Hospital, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa

IIIMB ChB, FCEM (SA), MMed (EM), Dip PEC (SA), DA (SA); Department of Emergency Medicine, King Dinizulu Hospital, Durban, South Africa

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Early cooling with 10 - 20 minutes of cool running water up to 3 hours after a burn has a direct impact on the depth of the burn and therefore on the clinical outcome of the injury. An assessment of the early cooling of burns is essential to improve this aspect of burns management

OBJECTIVES: To assess the rates and adequacy of prehospital cooling received by patients with severe burns before presentation to the Emergency Department (ED) at Edendale Hospital, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. Patients with inadequate prehospital cooling who presented to the ED within 3 hours were also identified

METHODS: A retrospective review of the burns database for all the patients with severe burns admitted from the ED at Edendale Hospital from September 2012 to August 2013 was undertaken. Demographic details, characteristics and timing of the burns, and presentation were correlated with burn cooling

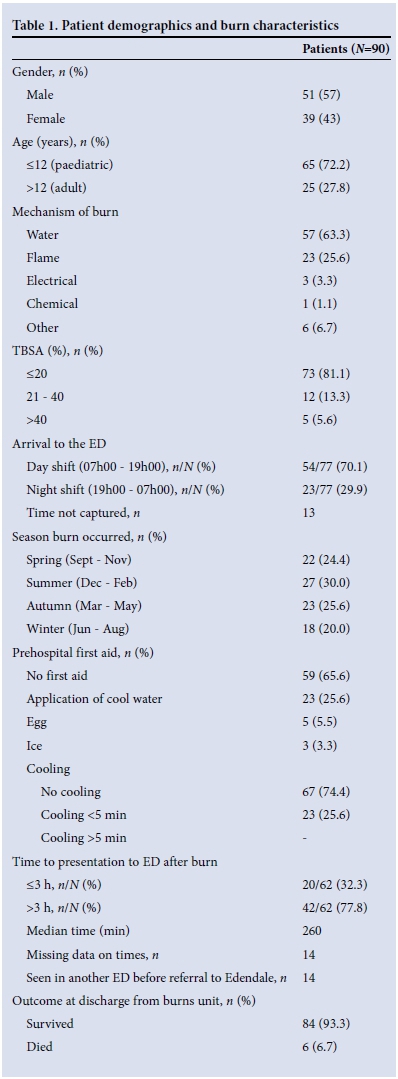

RESULTS: Ninety patients were admitted with severe burns. None received sufficient cooling of their burns, 25.6% received cooling of inadequate duration, and 32.3% arrived at the ED within 3 hours after the burn with either inadequate or no cooling. The median time to presentation to the ED after the burn was 260 minutes

CONCLUSION: Appropriate cooling of severe burns presenting to Edendale Hospital is inadequate. Education of the community and prehospital healthcare workers about the importance of early appropriate cooling of severe burns is required. Many patients would benefit from cooling of their burns in the ED, and facilities should be provided for this vital function.

There is a high prevalence of burns in South Africa (SA), with approximately 3.2% of South Africans suffering thermal injuries each year.[1] Burns are also one of the leading causes of disability-adjusted life years lost in low- and middle-income countries.[2] Timeous access of burn patients to appropriate medical care is vitally important to improve prognosis. Current optimal burn first aid involves the application of cool running water for 10 - 20 minutes as soon as possible after the burn, although cooling up to 3 hours after a burn has been shown still to be beneficial.[3] Early cooling of burns leads to less clinical and histological tissue necrosis, improves burn healing and helps relieve pain.[3-5]

In porcine studies, decreased histological burn depth was noted after 20 and 30 minutes of cooling over 5 and 10 minutes (p<0.05).[6] Delayed cooling of porcine burns for 1 or 3 hours also showed improved wound re-epithelialisation and decreased the amount of scar tissue that developed.[7] Burns with delayed cooling were also shown to have less necrosis than non-cooled burns. [4] Application of cool running water consistently demonstrated improvement in wound recovery compared with application of wet towels or cooling sprays (p<0.05).[8] Burns cooled with iced water showed increased necrosis.[4] In a study performed at the Royal Children's Hospital in Brisbane, Australia, children who received 20 minutes of cooling had significantly reduced time to re-epithelialisation (p=0.011).[9]

It is important to note that mortality is increased in hypothermic burn patients, as noted in a study performed in New York (60% v. 3%, p<0.001),[10] although the study showed that none of the patients who received prehospital cooling was found to be hypothermic.[10] The authors demonstrated that hypothermia was present in 35% of patients with a burn total body surface area (TBSA) of >70% and in 0.9% of patients with a TBSA of <70% (p<0.001), which would imply that extra caution should be exercised when cooling larger burns to avoid hypothermia.

Improvement in burn care would have far-reaching implications on patients' lives and on their communities, and any improvement in burn severity and depth would markedly affect hospital length of stay and use of hospital resources. The prehospital and emergency care of burns is an underemphasised responsibility of the healthcare system. Local and international studies confirm that prehospital management of burns is inadequate,[11-13] and the majority of acute burns are managed by emergency department (ED) staff without intervention by a burns specialist.[14]

Methods

A retrospective review of the burns database at Edendale Hospital, a large regional hospital in Pietermaritzburg, SA, for all patients with severe burns admitted to the burns unit and adult and paediatric intensive care units between September 2012 and August 2013 was undertaken.

Edendale Hospital is a referral hospital for many local district hospitals, community health centres and clinics. It also covers a large local population who have direct access to the ED. The Edendale burns unit is a designated specialist-run service with a dedicated high-care burns unit and theatre slates for burn cases.

Data collection

Information was gathered on a burns admission proforma for all patients with burns requiring admission by the ED staff on arrival to the ED. The data were then added to the burns database by the burns registrar. Only cooling performed by the patient, their family, bystanders or prehospital staff was recorded. Cooling performed by the Edendale Hospital ED staff was not included. Duration of cooling with water was documented as per the report given by the patient. Variables assessed included age, gender, time of burn, day of week, burn mechanism, burn depth, and burn size in relation to prehospital cooling and time to presentation. Data were recorded on an Excel spreadsheet.

Inclusion criteria

Patients with severe burns, which were defined as >15% TBSA in adults, >10% TBSA in children, >5% TBSA full-thickness burns and inhalational injury, were included.

Exclusion criteria

Burns not fulfilling the criteria for severe burns were excluded.

Study measures and statistical analysis

The data were analysed using Intercooled Stata version 11. Pearson's χ2 test and Fisher's exact test were used to test whether there was any association between the various demographic factors and burn characteristics, and reception of cooling. The level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Ethics

Ethics approval was granted by the University of KwaZulu-Natal's Biomedical Research and Ethics Committee (Ref. BE027/14). Approval was also received from the KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Health Research Committee and the management of Edendale Hospital.

Results

Ninety patients with severe burns were admitted during the period under review. Patient demographics and burn characteristics are set out in Table 1.

Four patients with flame burns and one patient with chemical burns died as a result of their injuries. A further patient died as a result of systemic sepsis. Of the patients who died, two had received some form of cooling.

No patient with severe burns presenting to the Edendale Hospital ED during the study period received adequate prehospital cooling, and only 25.6% of patients received any cooling with water, which was reported as <5 minutes of cooling. Only 32.3% of the patients presented to the ED within 3 hours of their burns.

Table 2 depicts the correlation of burn characteristics with cooling. The correlation of time to presentation to the ED with the administration of prehospital cooling is set out in Table 3.

Discussion

The near-complete absence of adequate cooling is in keeping with the results of other studies, including a study performed at another large regional hospital in KwaZulu-Natal, which demonstrated that only 1.1% of their burn population received 10 minutes of cooling within 3 hours of the burn,[11] and a further 26% received cooling of inadequate duration.[11] Internationally, prehospital cooling also appears to be inadequate. Only 33.9% of burn patients presenting to a Shanghai hospital received 'cooling therapy' of any sort. Of these patients, 88% received less than 10 minutes of cooling.[12] Only 51% of patients presenting to a UK ED had irrigated their burns with cool running water, for unknown durations of time.[13]

On further assessment of the 25.6% in our study who did receive some cooling, demographics and burn characteristics did not seem to have a significant impact on the application of prehospital cooling. With regard to mechanism of the burn, there was no difference in the reception of cooling. Flame-burnt patients received the same rates of cooling as hot water-burnt patients, and patients aged < 12 years received the same rate of cooling as adults. In addition, seasonal variation did not seem to impact significantly on prehospital cooling. A higher percentage of patients presenting to the ED during the day received some prehospital cooling, which was statistically significant. This could be attributed to easier access to water during the day and more layman assistance being available to the burn victim. However, this was a small sample and studies with a larger sample size need to be conducted.

The fact that almost three-quarters of this cohort consisted of patients aged <12 years emphasises the need for parent education on burns prevention and first-aid treatment of burns. Inadequate parental knowledge of appropriate first aid for burns has been demonstrated in developed countries with relatively good access to information and resources.[15] In a survey of parents who presented to a university hospital in the UK, only 32% had adequate knowledge of first aid for burns, and a further 40% had no or poor knowledge.[15] It was noted that parents who had attended a first-aid course performed better and that parents from lower socioeconomic groups fared worse, which may also be a factor in our study. Only 10% of parents attending the outpatient clinic at Sheffield Children's Hospital in the UK would give ideal first aid for a burn, with only 35% cooling the burn for an adequate period of time.[16]

The median delay to presentation to the emergency department of 260 minutes after the burn was less than the time noted in Ngwelezane Hospital in northern KwaZulu-Natal.[11] This may be attributed to patients being closer to the hospital, possibly more accessible transport, or better prehospital emergency response infrastructure in our setting compared with the more rural setting of the other study. With nearly a third of patients presenting to the ED within 3 hours of their burns without cooling, there is a large group who would still have benefited from burn first aid in the ED. This highlights the need for burn first-aid awareness on the part of ED staff as well, and appropriate facilities and protocols should be developed to address the issue. Dedicated taps or showers should be fitted in EDs to cool burns. Burns could also be cooled in the ED by using a jug and large basins. Wet towels have been shown to be less effective than running water, but their use may be more practical for larger burns.

With many burn patients being referred from primary healthcare clinics and others being transferred by paramedics, there is an even larger percentage who are having even earlier contact with medical professionals and would benefit from cooling of their burns. In a prospective study conducted in Western Australia, it was noted that the first medical contact was responsible for inappropriate first aid for burns in half of the patients.[17] In a study in the UK assessing different healthcare workers, 23% suggested applying ice to burns, which has been shown to be detrimental to their progression.[18] The authors concluded that knowledge of burn first aid on the part of healthcare providers is universally poor. Attendance at a first-aid course by healthcare providers improved the knowledge of burn first aid.[19] This further demonstrates the need for education of prehospital and primary healthcare medical staff on appropriate burns management, as they are usually the first point of medical contact for burn patients. Burn first-aid knowledge of the prehospital staff in our context needs to be assessed further. Attendance at first-aid courses and refresher burns courses should be encouraged to improve knowledge of initial burn care. Amendments to the burns management protocols of the paramedic services should include appropriate prehospital cooling of burns. Modified methods of cooling with a jug and basin may need to be implemented if no running water is readily available.

Further assessment into the reasons why the rate of cooling is so low in these patients needs to be performed. Possible reasons may include lack of awareness of the benefits of cooling and inappropriate facilities or resources to best cool burns. While primary prevention of burns is considered the ideal, significant reduction in mortality and morbidity can be achieved if treatment of burns is commenced early. This requires a team-based approach to management of burns and includes public education, easy access to medical care and early initiation of appropriate first aid. Public awareness campaigns should focus on burn prevention and safety, and on administering immediate, appropriate first aid after a burn.

Study limitations

This was a retrospective review of a database that relied on the accuracy of the data recorded. Missing data in the database could have influenced the accuracy of our findings.

Conclusion

It is evident that the first aid for patients with burns who present to Edendale Hospital is poor, and there is a need for widespread first-aid training of healthcare workers and the community. There needs to be a concerted effort to provide earlier access to healthcare for this community, and quality first-aid treatment for burns must be provided to patients who present to the Edendale ED early.

References

1. Matzopoulos RE. A Profile of Fatal Injuries in South Africa: Fifth Annual Report of the National Injury, Mortality Surveillance System. Cape Town: University of Cape Town and MRC Crime, Violence and Injury Lead Program, 2004. [ Links ]

2. World Health Organization. World Media Fact Sheet. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs365/en (accessed 4 June 2014). [ Links ]

3. Cuttle L, Kimble RM. First aid treatment of burn injuries. Wound Practice and Research 2010;18(1):6- 13. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2008.10.011] [ Links ]

4. Venter THJ, Karpelowsky JS, Rode H. Cooling of the burn wound: The ideal temperature of the coolant. Burns 2007;33(7):917-922. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2006.10.408] [ Links ]

5. Lonecker S, Schoder V Hypothermia in patients with burn injuries: Influence of prehospital treatment. Chirurg 2001;72(2):164-167. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s001040051286] [ Links ]

6. Bartlett, N, Yuan, J, Holland AJA, et al. Optimal duration of cooling for an acute scald contact burn injury in a porcine model. J Burn Care Res 2008;29(5):828-834. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/BCR0b013e3181855c9a] [ Links ]

7. Cuttle L, Kempf M, Liu P-Y, Kravchuk O, Kimble RM. The optimal duration and delay of first aid treatment for deep partial thickness burn injuries. Burns 2009:36(5):673-679. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2009.08.002] [ Links ]

8. Yuan J, Wu C, Holland AJA, et al. Assessment of cooling on an acute scald burn injury in a porcine model. J Burn Care Res 2007;28(3):514-520. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181855c9a] [ Links ]

9. Cuttle L, Kravchuk O, Wallis B, Kimble RM. An audit of first-aid treatment of pediatric burns patients and their clinical outcome. J Burn Care Res 2009;30(4):828-834. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181bfb7d1] [ Links ]

10. Singer AJ, Taira BR, Thode HC jr, et al. The association between hypothermia, prehospital cooling, and mortality in burn victims. Acad Emerg Med 2010;17(4):456-459. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00702.x] [ Links ]

11. Scheven D, Barker P, Govindsamy J. Burns in rural Kwa-Zulu Natal: Epidemiology and the need for community health education. Burns 2012;38(8):1224-1230. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2012.04.001] [ Links ]

12. Ji S, Luo P, Kong Z, et al. Prehospital emergency burn management in Shanghai: Analysis of 1868 burn patients. Burns 2012;38(8):1174-1180. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2012.03.010] [ Links ]

13. Khan AA, Rawlins J, Shenton AF, Sharpe DT. The Bradford burn study: The epidemiology of burns presenting to an inner city emergency department. Emerg Med J 2007;24(8):564-566. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/emj.2005.027730] [ Links ]

14. DeKoning EP, Hakeneworth A, Platts-Mills TF, Tintinalli JE. Epidemiology of burn injuries presenting to North Carolina emergency departments in 2006-2007. Burns 2009;35(6):776-782. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2008.09.012] [ Links ]

15. Davies M, Maguire S, Okolie C, Watkins W, Kemp AM. How much do parents know about first aid for burns? Burns 2013;39(6):1083-1090. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2012.12.015] [ Links ]

16. Graham HE, Sarah E, Bache SE, Muthayya P, Baker J, Ralston DR. Are parents in the UK equipped to provide adequate burns first aid? Burns 2012;38(3):438-443. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2011.08.016] [ Links ]

17. Rea S, Kuthubutheen J, Fowler B, Wood F. Burn first aid in Western Australia - do healthcare workers have the knowledge? Burns 2005;31(8):1029-1034. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2005.05.010] [ Links ]

18. Tay PH, Pinder R, Coulson S, Rawlins J. First impressions last ... a survey of knowledge of first aid in burn-related injuries amongst hospital workers. Burns 2013;39(2):291-299. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2012.05.013] [ Links ]

19. Skinner A, Peat B. Burns treatment for children and adults: A study of initial burns first aid and hospital care. N Z Med J 2002;115(1163):1-9. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2013.02.007] [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

D Fiandeiro

danielhasemail@gmail.com

Accepted 21 April 2015.