Services on Demand

Article

Indicators

Related links

-

Cited by Google

Cited by Google -

Similars in Google

Similars in Google

Share

SAMJ: South African Medical Journal

On-line version ISSN 2078-5135

Print version ISSN 0256-9574

SAMJ, S. Afr. med. j. vol.105 n.6 Pretoria Jun. 2015

http://dx.doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.9789

IZINDABA

Judge nudges dormant euthanasia draft law

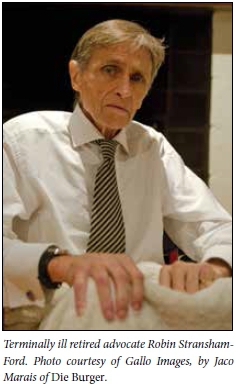

A terminally ill Cape Town advocate who died of natural causes hours before a Gauteng High Court judge granted him the locally unprecedented right to end his life (or have a doctor help him end it) may have speeded up long-recommended progressive law more in line with provisions of the Constitution.

Judge H J Fabricius of the Pretoria Division of the Gauteng High Court this April supported the 'development' of common law that predates the Bill of Rights and outlaws euthanasia. He said that serious consideration of new legislation based on the 1998 recommendations of the South African Law Commission was needed to bring the existing law more in line with constitutional provisions. The 1998 commission found in favour of euthanasia, as long as safeguards were in place to ensure that only terminally ill people in a sound state of mind could request and receive it. However, for 16 years Parliament has failed to act upon or even debate its recommendations.

Judge Fabricius's ruling - and the revival of the complex and hotly contested euthanasia debate - could be the catalyst that leading academics in bioethics and philosophy have been waiting for to enable a more pragmatic and human rights-based approach to severe, prolonged and unnecessary human suffering. The judge stressed that his ruling applied only to retired advocate Robin Stransham-Ford, who was 65, and did not change any existing laws prohibiting euthanasia, which would need to be challenged on the individual merits of each case. Assisted suicide or active voluntary euthanasia remains unlawful.

Suffering patient 'totally rational', wanted to die on his terms

He said Stransham-Ford, who was suffering from terminal stage 4 cancer with only weeks to live, was highly qualified, 'of vast experience' in the legal profession and knew exactly what he required and why. The applicant was psychologically assessed and found to have no cognitive impairments; 'in fact he impressed as being totally rational'. He had a good understanding and appreciation of the nature, cause and prognosis of his illness, plus the clinical, ethical and legal aspects of assisted suicide.

Stransham-Ford suffered from severe pain, nausea, vomiting, stomach cramps, constipation, disorientation, weight loss, loss of appetite, high blood pressure and increased weakness and frailty related to his kidney metastases. He was unable to get out of bed and had injections and drips. Unable to sleep without morphine or other painkillers, which made him drowsy, he endured anxiety related to dying while suffering, although he was not afraid of death itself. Lawyers for Stransham-Ford argued that, from a philosophical point of view, there was no difference between assisted suicide by providing the sufferer with a lethal agent or switching off a life-supporting device - or the injecting of a strong dose of morphine with the intent to relieve pain and knowing that the respiratory system would close down, leading to death. Stransham-Ford said in his affidavit that there was no logical distinction between withdrawing treatment to allow 'the natural process of death' and physician-assisted death, labelling this distinction 'intellectually dishonest'. Judge Fabricius said that while there was 'much to be said' for this view, he would 'leave it for the philosophers' and confine himself to the constitutional debate.

Stransham-Ford said in his affidavit that there was no logical distinction between withdrawing treatment to allow 'the natural process of death' and physician-assisted death, labelling this distinction 'intellectually dishonest'.

Sacredness of the quality of life

The right to life was at the centre of South Africa's constitutional values, establishing a society where the individual value of each community member was 'recognised and treasured', and therefore incorporated the right to dignity. Without dignity, human life was substantially diminished. 'I also agree with the warning that any pious uncoupling of moral concern from the reality of human and animal suffering has caused tremendous harm to mankind throughout the centuries.' Judge Fabricius said he agreed with Stransham-Ford's contention that it was a fundamental human right to die with dignity, which the country's courts were constitutionally obliged to advance, respect, protect, promote and fulfil. Contrary to what the respondents (the Minister of Justice and Correctional Services, the Minister of Health, the Health Professions Council of South Africa and the National Directorate of Public Prosecutions, plus Doctors for Life, admitted as 'friends of the court') had submitted, the sacredness of the quality of life should be accentuated rather than the sacredness of life per se. The norms of the Constitution should inform the public and its values, 'not sectional, moral or religious convictions'.

Judge Fabricius said it was 'unfortunate and disturbing' that societies acquiesced in thousands of deaths caused by weapons of mass destruction. They even seemed to tolerate a 'horrendous' murder rate, the 'daily slaughter on our roads', impure water and insufficient medical facilities. 'The state says it cannot afford to fulfil all social-economic demands, but it assumes the power to tell an educated individual of sound mind who is gravely ill and about to die that he must suffer the indignity of the severe pain, and is not allowed to die in a dignified quiet manner with the assistance of the medical practitioner.' The judge said an irony was that 'we are told from childhood to take responsibility for our lives, but when faced with death we are told we may not be responsible for our own passing ... one can choose one's career, decide to get married, live according to a lifestyle of one's choosing, consent to medical treatment or refuse it, have children and abort children, practise birth control, and die on the battlefield for one's country. But one cannot decide how to die.' The choice of Stransham-Ford was consistent with an open and democratic society and its values and norms as expressed in the Bill of Rights. There was 'of course' no duty to live, and a person could waive his or her right to life.

Inevitable abuse 'unlikely' - Judge

Judge Fabricius emphasised that any future court could determine the necessary safeguards 'on its own facts', saying that there was therefore no 'uncontrolled ripple effect', as was put to him by the respondents. He also disagreed with the respondents that his facts-based development of the common law would 'leave a void that will inevitably lead to abuse'. While the Ministry of Justice and Correctional Services attributed the original lack of action on the Law Commission's report to 'other priorities such as HIV and the AIDS epidemic', it did not say why the report was given no subsequent legislative attention.

The South African Medical Association (SAMA) Human Rights, Law and Ethics Committee cautioned health practitioners that the HPCSA's policies remained in force and said that 'any such activities' could result in disciplinary sanctions. It highlighted that the order applied 'only to this index case'. The committee emphasised the value of palliative care for the relief of pain and suffering for patients who were terminally ill and stressed that 'pain cannot be viewed as persuasive enough reason to resort to the extreme measure to end one's life'. SAMA did not support the right to die in law, euthanasia or doctor-assisted suicide, which was in line with the HPCSA's Policies and the World Medical Association's Guidelines and codes on the subject.

The respondents have filed appeals against the ruling, paving the way for a potentially even more far-reaching Constitutional Court ruling.

Chris Bateman

chrisb@hmpg.co.za